- Author

- Pacini, John

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 1975 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

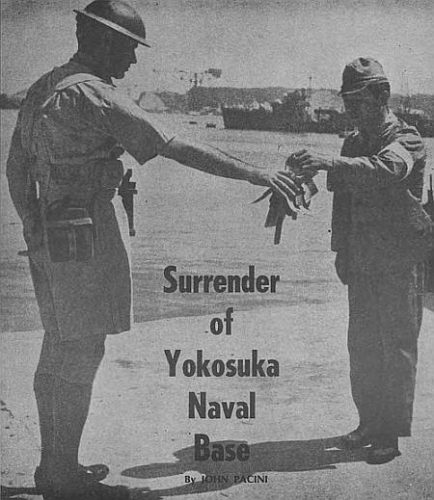

John Pacini was one of a team of war correspondents who covered the Japanese surrender. He took passage on HMAS Napier for the last important mission in the Pacific war. In this article he describes Captain Buchanan’s acceptance of the surrender of Yokosuka Naval Base on 30th August 1945. Pacini tells what the first landing party found and how the beaten Japanese received them.

AFTER BREAKFAST we saw the steep blue shores of Tokio Bay. Our three APDs (Assault Personnel Destroyer) were travelling in line with our ship in front. As we came to the head of the harbour, which had already been cleared of numerous mines by the Japanese and our own minesweepers, the party of New Zealanders who were to secure the island fortresses began their journey in their landing craft.

They landed around 9.30 a.m., and were quickly well implanted on them. They met no opposition. On the contrary, in each case, Japanese officers came down to the shore to meet them, carrying pages of information which the force might need.

About 9.45 a.m., marines landed at Azuma Peninsula, and at 10.40 the New Zealanders and Australians landed on the Japanese mainland at the Yokosuka base. Correspondents landed with Captain Buchanan. We left the APD in the usual type of landing craft, and after a few minutes travel, entered a small basin.

At the end of it, and waiting under a verandah, which was joined to the roof of a storehouse, stood three Japanese. As the landing craft sidled up to the small jetty, Captain Buchanan jumped ashore (making him the first Australian to land in Japan), and, with a guard behind him, went straight to where the three nervous Japanese were standing. They saluted Buchanan, who returned the compliment.

Then a Japanese standing in the centre of the group bowed low, and handed over a large ring of keys, which opened every door in the area. This Japanese was a Naval Commander, who had been in charge of the stores depots of the base. The men on each side of him were interpreters. A guard of Australian sailors quickly formed up beside the Japanese.

Instead of wearing the usual jungle-green battledress which we associate with all Pacific landings, the sailors, who were part of the British Pacific Fleet occupational force, went ashore in freshly-laundered khaki shirts and shorts, highly polished boots, shining brasswork, and steel helmet.

A table was erected quickly, and on it were placed the plans of the area which Buchanan studied in conjunction with the Japanese. The interpreters were good, and information was gathered quickly.

Although the landing was British, it might well have been Australian, judging from the scene around the table. The guard was Australian, and the whole of Captain Buchanan’s headquarters was composed of Australian naval officers, who had been taken from the destroyers Napier and Nizam. Having made a thorough inspection of the maps, Captain Buchanan and his party began a tour of the area. Large files which the Japanese Commander had brought with him for perusal were handed over to an American Navy interpreter for translation.

The Japanese Commander told us that almost all the office records had been burnt on the orders of higher authority.

During our initial tour we saw Japanese policemen for the first time. As we expected, they were dressed in black and carried swords. The Japanese policemen seem a better class than the general run of Japanese, and certainly demand much respect from civilians. They were courteous without being patronising, and helped the occupation forces everywhere.

Four large storehouses, a number of caves, and a dozen or more Japanese ships, including everything from small tugs to destroyer escorts and landing craft, are in the area which has become our responsibility. The storehouses were filled with equipment, both for personal issue and for issue to ships.

Throughout the tour of the area almost all Japanese we saw were perceptibly shaken; and I don’t think any of them would have been surprised had we suddenly shot or bayoneted them. They took us through the caves which had been burrowed in the hillsides beside the naval base.

One of these was a complete block of offices, with telephone communication and steel files, where the headquarters moved as a body when our planes were overhead.