- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Naval technology, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Adrian Rose

In 1644 the Duke of York and Albany’s Maritime Regiment of Foot was raised to protect the crews of Royal Navy warships from attack by French sharpshooters. This first ‘official’ unit of naval infantry evolved into the Royal Marines. What is less well known is that some 275 years later the British Army was called upon to provide protection for merchant shipping operating in Home Waters and around the world.

Historical background: Britain’s Maritime Trade

Britain’s island geography and dependence on imports leaves her vulnerable to blockade, as was demonstrated in 1917 when there was less than six weeks supply of foodstuffs remaining in the country. Twenty years later, Britain’s fleet of coasters and general traders had shrunk by more than 4000 ships, making the protection and safe passage of merchant shipping an even greater necessity. In 1939 Britain imported half of all its food requirements, most of its raw materials and all of its oil. The greater part of this trade was transported by Britain’s Merchant Navy or in ships from around the Empire.

Outbreak of War

On 3 September 1939 Germany declared that all British merchant vessels would be treated as warships and open to attack. Less than nine hours after Britain’s entry into the war the British liner SS Athenia, sailing from Liverpool to Montreal, was torpedoed by a German submarine 250 miles off the Irish coast and sunk. On 11 September Churchill announced to the Shipping Defence Committee his intention to ‘arm a thousand merchant ships.’ On 24 September Germany abandoned all treaty rules governing the conduct of war at sea. The following month a German Naval War Staff Memorandum set out Berlin’s policy; ‘Germany’s principal enemy in this war is Britain. Her most vulnerable spot is her maritime trade. The principal target of our naval strategy is the merchant ship.’

DEMS Organisation

Administered by the Admiralty’s Trade Division, the Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship (DEMS) organisation was responsible for the arming of merchant ships, the training of gun crews and the allocation of servicemen. Personnel were provided by the Admiralty (Royal Navy ratings and Royal Marines), the War Office (soldiers) and the Ministry of War Transport (merchant seamen). On larger ships it was common to find Army and Royal Navy gun crews working in separate teams, sometimes assisted by merchant sailors. Numbers reached a peak in November 1943, with 40,000 DEMS gunners operating out of 46 DEMS bases at home and 50 abroad.

DEVELOPMENT AND ORGANISATION

Cross-Channel Traffic

Starting in late 1939, British soldiers were employed in a defensive role aboard civilian ships in a variety of ad hoc, short term naval commitments. Troops served in anti-aircraft paddle steamers operating in the Thames Estuary, as well as aboard train ferries and leave boats crossing the English Channel.

On 9 January 1940 Germany started air attacks on British convoys and general shipping. In the following month the use of troops for the Anti-Aircraft Defence of Merchant Shipping and the provision of Anti-Aircraft Light Machine Gun Troops was approved at a meeting of a Cabinet Special War Committee. Two hundred trained soldiers with 100 LMGs, operating initially from the Port of London, were assigned to protect east coast shipping. In March the army called for volunteers for unspecified ‘secret work at sea’ and ‘special sea duties’. In April two Light Anti-Aircraft Troops, Royal Artillery were established at Southampton and Dover to assist in providing manpower for cross-Channel traffic. Two months later an extra 420 men were provided for east coast work.

Bren Gun Scheme

With the fall of France in June 1940 German air attacks against east coast shipping intensified. The situation became so serious that the government asked the Admiralty to provide protection. Unable to spare naval personnel for the task, the War Office agreed to supply 940 soldiers and 470 machine guns as a temporary measure.

Sea-going soldiers needed to be trained machine gunners, so they came mostly from infantry and armoured regiments. The first soldiers deployed just days after the official establishment of the Bren Gun Scheme on 27 February 1940. Operating initially around Britain’s eastern and southern coastlines in two-man teams on small coastal vessels, it proved such a success that the army’s role expanded and numbers increased. In the autumn of 1940 Army Council Instructions requested units to publish a Part One daily order asking for volunteers for ‘sea-going special duties’.

Coastal Shuttle Service and Port Gunners, Royal Artillery

In August 1940 the War Office formed the Coastal Shuttle Service, which provided additional troops for seagoing duties along the east coast. Soldiers joined their vessels prior to sailing and returned to their base on returning from sea, bringing their machine guns back with them. This left ships defenceless against air attack whilst in UK harbours. It was therefore decided to provide soldiers to man guns on ships in port, so in October 1940 2000 Royal Artillery soldiers were enrolled as Port Gunners. In February and March 1941 a further 4500 Royal Artillery gunners were allocated to man light anti-aircraft guns and Bofors 40 mm guns on ocean-going ships. In September 1941 the Port Gunners were disbanded as air attacks on British ports decreased, and the men transferred to sea-going duties.

Maritime Anti-Aircraft, Royal Artillery

On 6 May 1941 the Royal Artillery assumed control of operations previously undertaken by the Bren Gun Scheme and Coastal Shuttle Service. A new formation, designated Maritime Anti-Aircraft, Royal Artillery, was created, comprising a headquarters, four regiments and seven batteries, all based close to major estuaries: Clyde, Forth, Tyne, Mersey, Thames and Severn. There were 39 Detachments at UK ports and four overseas. In July 1942 the Eastern Shuttle Service was established in Bombay to cover the regions of India, Ceylon and South Asia. In October 1942 a further 3000 men were provided to meet the demands of Atlantic and North Russia convoys. In December the same year, overseas units were formed in America, Australia, Canada and Egypt. Between 1941 and 1942 inter-service discussions took place over proposals to transfer maritime soldiers to the Royal Navy or Royal Marines, but the idea was dropped.

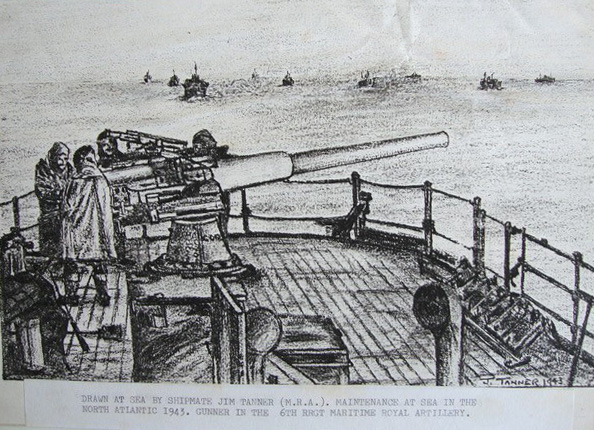

Maritime Royal Artillery

As the war progressed attacks by enemy aircraft diminished, with submarines and surface ships becoming the main threat. To reflect the change in role, the formation’s title was changed to Maritime Royal Artillery on 1 November 1942. In the following March the establishment was reorganised into six UK regiments, each comprising an RHQ, Training Battery, Holding Battery and Port Detachments. Overseas Batteries and Troops were established in North Africa and Palestine, and later on in France, Belgium and Holland. By the end of the war over 30 units had operated overseas. In August 1944 1800 maritime gunners were returned to general service, and further reductions took place the next year. Following the cessation of hostilities in August 1945, maritime gunners were transferred to other regiments and corps to assist in the tasks of occupation and reconstruction. The last maritime regiment was disbanded on 31 July 1946.

Training

Military training was undertaken at battery and regimental locations and included gas drills, aircraft recognition (model planes and films), gunnery practice on static guns and in a Dome Teacher, and live firing on shooting ranges. Soldiers who passed a Royal Navy gunlayers course were entitled to wear a naval trade qualification badge on their uniform. Nautical training was conducted at a local Royal Naval Reserve unit or DEMS base. Rope work (tying knots and slinging a hammock), seamanship (rowing and climbing rope ladders) and the use of naval guns was taught by naval staff. Swimming and lifesaving lessons were given at public pools.

Shore Based Duties

Clerks, storemen, drivers, medics, mechanics and gunnery instructors were employed at battery and regimental headquarters, port detachments and DEMS bases in Britain and abroad. Some units in Britain were assisted by women of the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

Reasons for Volunteering

Individuals volunteered for sea-going service for a variety of reasons. Many men, having heard of the horrors of trench warfare from a father or uncle, resolved to join the Royal Navy or Royal Air Force. But there were more applicants than places available, so most found themselves conscripted into the army. Such men now had an opportunity to avoid serving in the infantry. Soldiers who had served in Norway or France saw an opportunity to recover wounded pride and avenge the death of fallen comrades. Foreign destinations and warmer climates enticed the more adventurous. It was also an escape from the boredom and drudgery of life in a military camp, with the routine of kit inspections, parade ground drill, route marches, guard duties and fatigues.

At the start of the war an infantry private was paid two shillings a day – less than his Royal Navy, Royal Air Force and Merchant Navy counterparts. Married men were compelled to allot part of their pay to their family. A great many volunteers were attracted by the promise of extra pay (sixpence a day). Lengthy negotiations took place between the War Office and ship owners over who should bear the cost of protecting shipping company assets. No agreement was reached, so the pay was not forthcoming. However, men were sometimes offered the chance to earn extra money aboard ship by undertaking non-military duties such as cleaning and painting, cooking, shovelling coal into engine room boilers, and unloading cargo.

There was no lack of volunteers to serve at sea, but for a small number of men, their transfer was not voluntary. Some commanding officers, wanting to meet manning quotas or rid themselves of unwanted soldiers, reassigned individuals or groups of men without their knowledge or consent.

OPERATIONS

Assignments

Once trained, soldiers waited to be assigned to a ship. An individual or group of men would travel to the port of embarkation and report aboard ship. They knew neither its destination, the length of the voyage, nor when they would leave the vessel. Prior to the war Britain had signed an international maritime treaty prohibiting the use of service personnel aboard merchant ships. To get around this legal restriction, DEMS gunners signed-on as Deck Hands, and are listed as such in Crew Lists. Having signed on, they were informed where they were sailing to and settled into their temporary home.

At the start of the war two-man teams sailed in trawlers and small coastal vessels on short trips around Britain’s coast. As the war progressed voyages became longer and the ships larger. It was not uncommon for a man to be at sea for a year. Tankers were the most dangerous ships to serve in. Their valuable cargo ensured they were singled out for attack, and when hit would explode in an enormous ball of flame, setting the

sea ablaze. Less combustible but no less lethal were ore carriers, which sank in a matter of minutes due to their heavy cargo. At the opposite end of the scale, a transatlantic liner such as the Queen Mary carried up to 200 military and naval gunners to protect some 15,000 troops taking passage.

It was rare for a gun team to stay in the same ship or even serve together in another vessel (Bofors gunners were an exception). I know of one man who sailed in 14 ships during four years of maritime service. Officers seldom went to sea, and when they did it was usually as Gunnery Officer in a larger ship or passenger liner. Despite the isolated and temporary nature of their assignments morale and loyalty were high, and there was great pride in belonging to an exclusive, though little-known, branch of the army.

Life at Sea

The main duties of a maritime gunner consisted of operating and maintaining the weapons and defensive equipment. They were also used as lookouts. Correct identification of aircraft was vitally important, not only to differentiate friend from foe, but because it would indicate what tactics may be employed against the ship.

Watches usually comprised four hours on, four hours off, or four on eight off if numbers allowed. All ships’ gunners ‘stood to’ during Action Stations, a state which could last many hours, sometimes several days. Weapon cleaning and practice took up a large amount of time. Some men learned to read signal flags. Gunners were sometimes called on to shoot at drifting mines using rifles, and often mounted anti-sabotage watch while in port.

On arrival at their final destination the ship was boarded by a shore-based maritime officer. He inspected the guns, ammunition and soldiers, and pointed out any shortcomings. The gun team then disembarked. If in the UK they returned to their base by train; when abroad they were sent to the local maritime or DEMS unit. All returnees underwent a dental inspection, a medical examination to check they were Free from Infection, replaced lost or damaged kit, and went on a short period of leave. Men whose ship had been sunk were granted 14 days Survivor’s Leave. On returning to camp they underwent two weeks of aircraft recognition and gunnery training, and awaited their next posting.

Defensive Equipment

Merchant ships carried a range of defensive measures to protect them against attack. Physical protection such as sandbags, concrete slabs and plastic armour was placed around the wheelhouse, bridge and gun pits (tubs). Mine countermeasures included paravanes, wiping and degaussing coils, and Admiralty Net Defence equipment acted as anti-torpedo protection.

Soldiers assisted ships’ crews with kites and barrage balloons, installed to counter low-level and dive bombing air attacks. Kites were used in British coastal waters but were prone to crash onto the deck. Barrage balloons were used in UK waters and the Mediterranean, where attacks from aircraft were more likely. The balloon or ‘blimp’ hung from a four-thousand-foot metal cable.

Weapons

The quantity and type of armament depended upon availability, size of ship and destination. Ships sailing around the British Isles were lightly equipped, vessels travelling to north Russia the most heavily armed. Weapons were grouped into four general types: machine guns, rocket weapons, naval guns and anti-aircraft cannon.

Machine Guns

Ships engaged in short voyages around Britain’s coast were considered less vulnerable to attack, so received only light anti-aircraft protection. At the start of the war this often consisted of a single machine gun, usually a First World War stripped Lewis (a Lewis gun minus its cooling shroud), or a Marlin, Hotchkiss, Vickers or Browning. Older guns were gradually replaced by the modern Bren gun. Gun mountings could be fitted to handrails and superstructure to provide a stable firing platform.

The machine gunner employed a technique known as ‘aiming off,’ aiming at a point ahead of the aircraft. The observation of fire was assisted by the use of tracer rounds, which glowed red in flight. There was a danger that an over-enthusiastic gunner could spray his own ship and colleagues with bullets, particularly if firing from the hip using the ‘hosing’ technique. To counter this, safety guards were fitted to restrict arcs of fire.

In the early days of the war a two-man gun team would carry a Lewis machine gun in a wooden box, four full drum magazines, a box containing 1000 rounds of ammunition, a metal gun mounting with four fixing bolts, together with cleaning kit and tools. As well as carrying his weapon, the soldier was required to take along two pairs of sea boots, duffle coat, hammock and blanket, tropical or Arctic wear as necessary, together with civilian clothes for use when ashore in neutral ports. Transporting all this kit when travelling by train was no easy task, and hauling it up a ship’s ladder was a test of strength and ingenuity.

Rocket Weapons

Following the evacuation of the BEF from France there was an acute shortage of machine guns and artillery. It was recognised it would take time to replace losses and build up stocks, so the Admiralty turned to its Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development to provide a temporary solution. Speed of manufacture and cost were the driving factors, so effectiveness was often less than ideal. Improvised equipment was difficult to operate, gave inconsistent results, and could be dangerous to those around them. A flame-thrower was fitted to a few vessels sailing between the Thames and the Forth, but proved to be unreliable. Rockets were volatile and had to be handled with great care. Projectiles and their trailing cables became entangled with masts, rigging, aerials and funnels, leading some ships’ Masters to ban their use entirely. Here is a selection of equipment used:

Pig Trough

The gunner sat inside a steel cabinet with seven rockets on either side, each carrying a 2-pounder shell. Crew of four plus two ammunition handlers.

Gymbal

Two projectors each fired a salvo of eight rockets with explosive heads. Crew of two plus two ammunition handlers.

Type J

A rocket propelled an exploding charge on a cable to a height of 750 feet which then floated down on a 62-inch parachute.

Pillar Box

The operator sat inside a circular swivelling cabin with two banks of ten rockets fitted to the outer casing. Fired in salvoes of 10 or 20 rockets, which burst 1500 yards from the ship like an artillery barrage. Crew of three plus two ammunition handlers.

Parachute and Cable

A rocket carried a steel cable 400 feet into the air which then floated down on a parachute. It could wrap around an airplane propeller or tear off a wing. It was claimed its use caused German pilots to abandon attacks at masthead height.

Fast Aerial Mine

Like the PAC but with 1000 feet of wire carrying a charge which exploded on contact. There was no sighting system, so aiming was done by eye. Crew of two.

Harvey Projector

Fired a nine foot long rocket carrying a 14-pound explosive shell up to 4000 ft. When fired, a 15-foot flame shot out the rear. Two operators.

Holman Projector

Compressed air (later steam) propelled a hand grenade 600 feet into the air (1000 feet on later models). The operators had to dive for cover to avoid being showered by shrapnel. Steam was not always of sufficient pressure, causing the grenade to fall back onto the deck. Nicknamed the ‘potato thrower’ as crews took to firing potatoes at friendly ships sailing alongside. Two operators.

Naval Guns

At the start of the war larger vessels were fitted with an old, often obsolete, low-angle breech loading deck gun at the stern to counter surface raiders and submarines. International law prohibited them from being fitted at the front of a ship. As the war progressed they were replaced with dual-purpose high-angle/low-angle guns which could fire at aircraft. Five types of gun were used (6-inch, 4.7-inch, 4-inch, 12-pounder and 6-pounder). Typically crewed by a team of four, assisted by two ammunition carriers who were sometimes merchant seamen.

Engaging the enemy began with shooting a single round at the target, observing the fall of shot and correcting the point of aim. A left or right alteration was made and another shot fired. Once the correct line of fire had been found, a plus or minus adjustment was applied to the range. The goal was to bracket the target with a shot landing in front and behind, and then make a final adjustment to register a hit. This process would typically take five or six rounds, and once on target, rapid fire was employed. Firing at a moving target from a ship which was pitching and rolling was no easy task, and considerably more difficult when being fired upon by the enemy.

Anti-Aircraft Cannon

The two most effective (and popular) weapons were the 20 mm Oerlikon and 40 mm Bofors anti-aircraft auto-cannons. This was due to their reliability, heavier shell, faster rate of fire and greater range. The 20 mm Hispano-Suiza was less successful. The Oerlikon fired 450 rounds per minute to a range of 1000 yards, its operator strapped into a harness. The Bofors fired a maximum of 120 rounds per minute to a height of 23,000 feet. It was crewed by a team of five, and only operated by army DEMS gunners. Both weapons were aimed using a cartwheel sight. The general rule was: don’t fire too soon, lead don’t lag the target, and watch the aircraft nose not the tracer.

Operation PEDESTAL

Perhaps the costliest action for maritime gunners was Operation PEDESTAL, sometimes remembered as the SS Ohio convoy to Malta. On 2 August 1942, 14 merchant vessels with a strong naval escort sailed from the Clyde for Malta with desperately needed fuel and supplies. Only five ships, four of which were badly damaged, arrived at their destination. Of the 162 maritime soldiers who defended the convoy (five of whom were officers), 19 were taken prisoner, 49 arrived safely in Malta, 64 were rescued at sea and 30 died.

Strength and Losses

Numbers peaked in September 1944 when there were 157 officers and 14,121 soldiers serving in the Maritime Royal Artillery, most of whom went to sea.

During the course of the war some men were captured by the enemy or interned by neutral powers. I know of 67 who were made prisoners of war, some ending up in prison camps in Germany. I have collected the names of 1470 men who lost their lives, five being officers. Most were killed in action, drowned at sea or died while adrift in a lifeboat. A few were executed by their Japanese captors. Maritime soldiers were sometimes mistakenly classified as merchant seamen in official records, so the true number of deaths may never be known.

Medals

Soldiers were eligible for campaign and service medals and military, naval and civilian bravery awards. Dutch, Norwegian and Polish governments issued awards to soldiers who served in their ships. Russia gave medals to some men on Arctic convoys. Britain belatedly instituted the Arctic Star in 2012.

Commemoration

The dead are commemorated on regimental memorials around Britain. Additionally, the names of men who died at sea with no known grave are recorded on Naval Memorials at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth. The DEMS plot at the National Memorial Arboretum displays the badge of the Maritime Royal Artillery. The Royal Artillery Commemoration Book, some 800 pages long, devotes four-and a half pages to the activities of the maritime artillery, two of which cover a single convoy to Malta.

During the war a short official docu-drama called Soldier-Sailor was released to the public. Filmed at Pinewood Studios and on location in the Mediterranean Sea, Egypt and Italy, the cast was drawn from each of the six maritime regiments. It is available to view on YouTube.

Regimental Motto

The battle honour of the Royal Regiment of Artillery is Ubique ‘Everywhere.’ The motto of the Maritime Royal Artillery was Intrepid per oceanos mundi ‘Boldly over the oceans of the world.’

Admiralty Publications

BR 219 Notes on Gunnery for Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (1940)

BR 254 The Eyeshooting Pocket Book (1941)

BR 282 DEMS Pocket Book (1942 and 1944)

The Maritime Royal Artillery in Australia

British Army DEMS gunners visited Australia in two contexts; Australia was the destination of a ship they were travelling in, or they were stationed in the country.

The Australian ship MV Rabaul had a DEMS detachment with both RANR and British Army personnel, including Able Seaman Victor Eyers RANR and Lane Bombardier William Fisher from the British Army. When Rabaul was sunk by the German raider Atlantis on 14 May 1941 Eyers was wounded and later died, whereas Fisher survived.

In July 1942 a staff of eight officers and 113 ORs set up headquarters in Bombay, with Port Detachments at Bombay, Karachi, Colombo, and Fremantle, Western Australia.

The Admiralty-issued BR 282 DEMS Pocket Book (1942) lists, there being Eyeshooting Schools and AA Ranges at Melbourne, Flinders and Sydney, and DEMS Bases and Sub-Bases at Fremantle, Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane.

In December 1942 a reorganisation of maritime units was undertaken, with 2 Troop (Australia) at Fremantle moving its HQ to Sydney the following month. In April 1943 220 maritime gunners left the Clyde in two ships for India and Australia. The draft spent six weeks in Durban before going on to Bombay, where some 40 men departed for Australia under the command of Captain Casson.

In February 1945 staff at 2 (Independent) Troop (Australia) at Sydney were increased to form 12 (Oceania) Battery, with its HQ at Sydney.

By the end of 1945 all overseas Troops and Batteries had returned to the UK and been disbanded.