- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Cerberus (Shore Establishment)

- Publication

- December 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

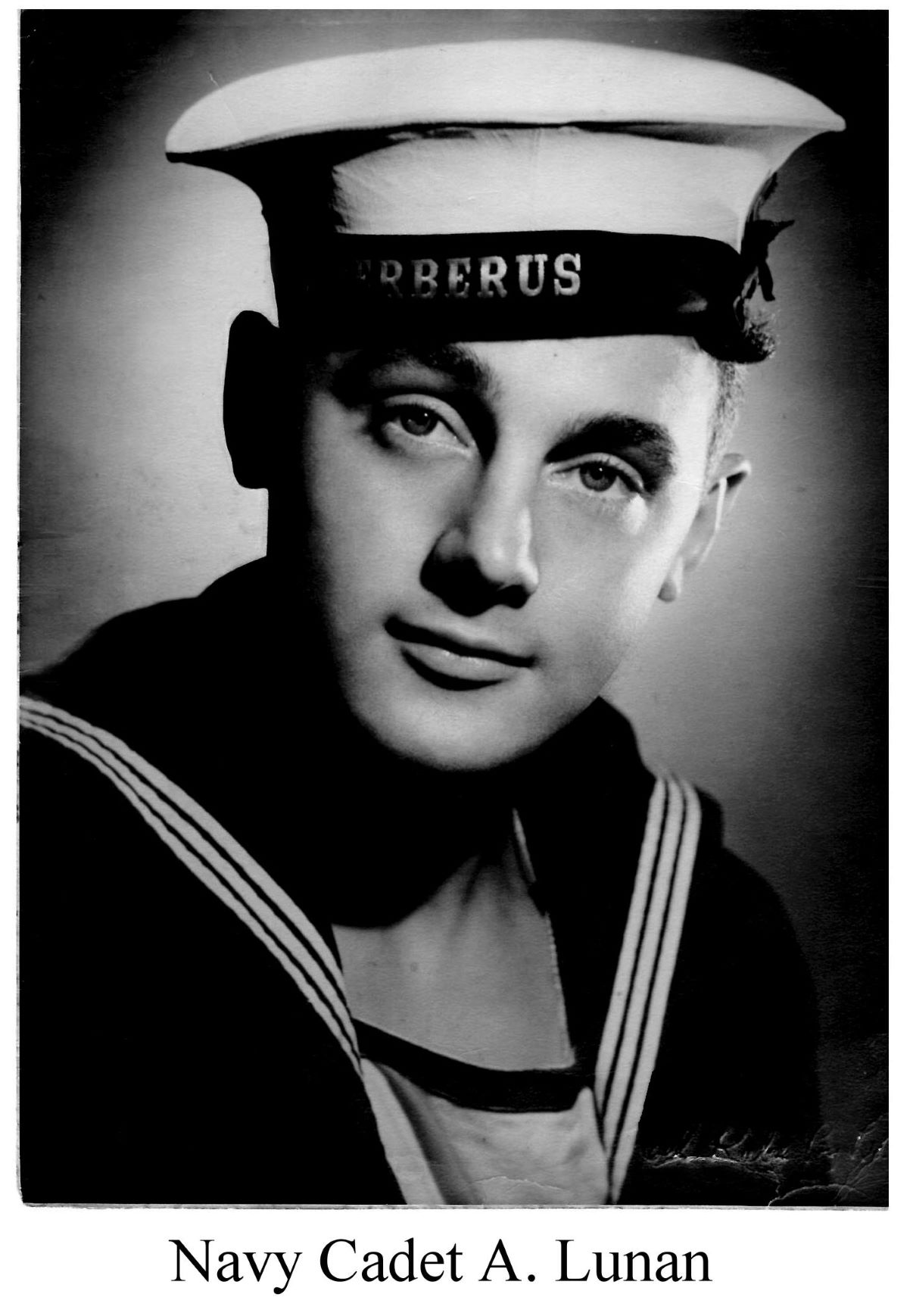

The late Arthur Lunan maintained a diary of his wartime service in the RAN from 1941 to 1946. His brother-in-law William Moody has digitised this and added some family photographs. William and his sister (Arthur’s widow) have given the Naval Historical Society permission to publish this material which is being serialised over a number of editions. This initial part of the story covers Arthur’s entry into the RAN and initial training at HMAS Cerberus where he becomes an officer candidate.

Introduction

Second World War veteran Arthur Daniel James Lunan has left us a remarkable and invaluable record of the various aspects of his long and eventful life. It is a first-hand account stretching from his childhood in the dire days of the Great Depression to the second decade of a new millennium and spanning some of the most momentous events of the war in the Pacific.

Remarkable in detail, it includes descriptions in his own words of the time immediately preceding his enlistment in the Royal Australian Naval Reserve, his subsequent training prior to his first posting and, from the contents of his Midshipman’s Journal, his experiences aboard HMAS Kanimbla. The remainder of his wartime service has been pieced together from the results of research into a variety of archival sources.

It is this portion of his life story that is the subject of this document – the journey of a seventeen-year-old butcher’s helper from the leafy suburbs of Sydney to the beaches of war-torn South-East Asia. It has been divided into three sections reflecting the various stages of his own personal wartime odyssey.

Part 1: From Rover Scout to Midshipman is the description of life as a child of the Great Depression in suburban Sydney during the early years of the Second World War; his later enlistment followed by basic training at Flinders Naval Depot, Victoria and subsequent selection for ‘Special Services’ training at HMAS Assault, Port Stephens NSW; his commission as a Midshipman and subsequent posting to Kanimbla on 12 January 1944.

Part 2: A Midshipman’s Journal. Kanimbla was a former coastal passenger liner requisitioned for war service and converted firstly to an armed merchant cruiser and later to L.S.I. (Landing Ship Infantry). As a RANR Midshipman (and later, Sub-Lieutenant), Arthur was required to keep a daily journal for the duration of his time aboard. This chapter contains extracts from this journal, concentrating on the more compelling incidents and observations, some being accounts of actions under fire in the South-West Pacific Theatre.

Part 3: After Kanimbla. Arthur’s next posting was to far north Queensland to train for upcoming amphibious operations in the South-West Pacific with the 1st Australian Beach Group (Commando). After long months of training he is involved in combined operations on Morotai and Borneo, embedded with an army unit during Allied landings and mopping up operations in Borneo. His transfer to HMAS Glenelg at the end of hostilities sees Arthur involved with the transfer of control in British North Borneo from Japanese occupational forces and the repatriation of Australian prisoners of war.

Part 1: From Rover Scout to Midshipman

Arthur begins: At the age of sixteen, I was able to obtain a licence to ride a motorbike, so my employer (a local Sydney butcher) bought a Triumph with a box side-car for me to do the home deliveries with. This service was a considerable part of the business in the days before housewives drove their own cars and there were no supermarkets.

Scouting was still a big part of my life and my main recreation. Many weekends involving camps, competitions and other scouting activities were spent with mates, all Scouts or Rovers like me. It was not until I was seventeen that at last I asked a girl out – for a cruise around Sydney Harbour on a yacht, organised by 2nd and 3rd Lindfield Rover Crew. Ibravely asked her out again – this time to the pictures on a Wednesday, one of my few free nights.

All this took place toward the end of 1940 with the war starting to affect our everyday lives. Petrol was rationed and home deliveries were banned to any house within a mile of the shop. Still, there were now coupons required for many things like fuel and clothing, so there existed a lively trade for what was wanted.

Conscription at age eighteen had taken up many youths who would otherwise have been looking for work. Whilst there had been no money available to reduce unemployment before 1940, suddenly there was plenty to put into the war effort.

As far back as my memory goes, I had always wanted to join the navy. This had been influenced by my grandfather Daniel William Cahill (Bill), who had been a member of the naval forces that occupied German New Guinea in late 1914. Grandfather1 gave me a sailor’s cap when I was about six years old and I wore it proudly for a while until its size defeated me and it disappeared into the limbo of forgotten things.

Enlistment

Approaching the age of twelve in 1936 and doing well at Chatswood Primary School, I had sent for the application forms to become a Cadet Midshipman. When my father read a penalty clause which required a refund of the £75 bond should the cadet be dismissed for any breach of discipline, he immediately knocked the idea on the head – any threat to his beer money was to be avoided at all costs!

Come WWII and in 1940, aged 16, I tried to enlist but was told to come back next year. At 17 it was possible to join the navy with parental consent, but Dad withheld permission until an army call-up was approaching. Finally, in July 1942, aged 17 and 10 months, I enlisted and was called up on 10 August.

A band of a dozen young adventurers mustered at Sydney’s Central Station on the last afternoon; goodbyes were said to parents, family and girlfriends. We joined a steam train for the first leg of a long trip to Flinders Naval Depot at the southern end of Victoria. A group of Queensland recruits were already aboard having spent most of the day wandering around Sydney, and some were a bit under the weather. At that time I didn’t smoke or drink, was a Rover Scout and, until the previous week, had been a Troop Leader with a King’s Scout Badge. The world was about to open up for me.

Flinders Naval Depot

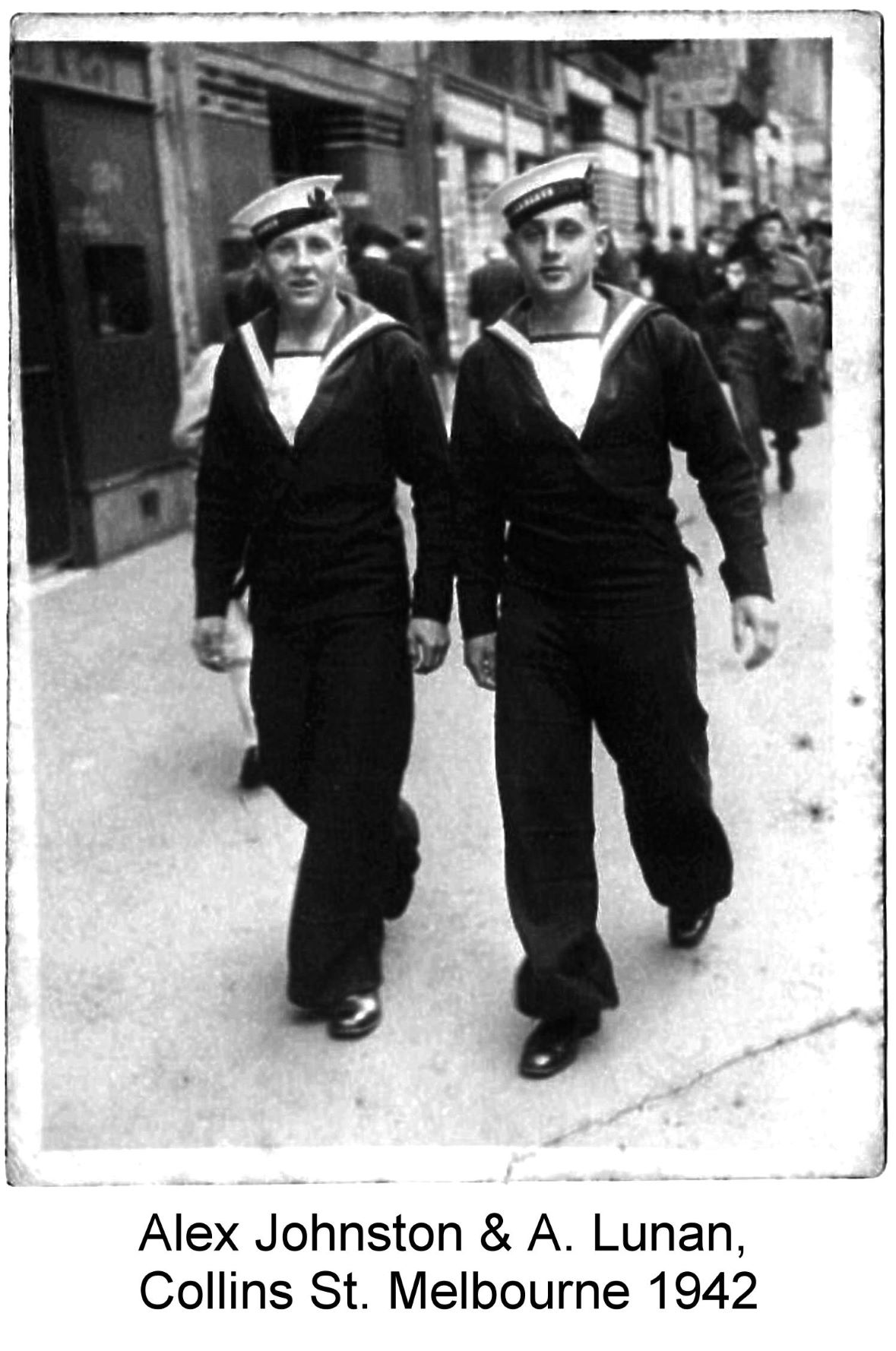

In my group was an old schoolmate from North Sydney Boys’ High, Alex Johnston, so we naturally stuck together. The trip seemed endless with a change at Albury for the change in gauge.2 Finally, we arrived at Flinders Street Station, Melbourne and caught a local train for Crib Point, our contingent now bolstered by a large number of Victorians.

I find it hard to remember the feeding arrangements on the trip, but at last Flinders Naval Depot was reached. Several important people – Petty Officers as we later discovered – with much shouting organised us into groups according to classification: Seamen, Cooks, Signallers etc., and then formed these groups into classes of about thirty. Johnno and I were in Class 160 and allocated to F Block in the New Entry School.

Each block contained a number of dormitories and ablution facilities and was home to two classes. Furniture was spartan – wooden tables and benches set out in a T-shape, hammock rails above, a hammock bin in one corner and clothing lockers down one wall – small lockers, as all a sailor’s gear (rig) is folded, nothing hanging up. There was also a dryer and a heap of mess gear set out on a table in a planned array. The floor in this fairly old building was of highly polished timber – the work of many recruits over the years.

The first issue on arrival was a hammock already stencilled with our names and containing one large beautiful woollen blanket – supply your own pyjamas. The hammock was slung between the rails at night about six feet above the deck and was comfortable to sleep in – with practice! We soon learned not to roll about when asleep but during the first few nights there were a number of crashes and groans.

Next came the all-important ‘Police Card’, to be carried at all times in the depot and to be left with the Police Office if leaving the base for any reason. Recruits over 25 had a red line on their card which allowed them to use the ‘wet’ canteen3– under 25, you could only use the ‘dry’ canteen. I don’t–remember any other concerns for the welfare of the young recruits – some only just 17 during my time in the navy and this attitude was rather hypocritical, as I later discovered.

Meals were good, cooked in a huge galley with up-to-date facilities and drawn for each meal by rostered mess-cooks from each class according to numbers present. Tea and cake at 4.00 pm was the one luxury we enjoyed.

The day started with a bugle call at 6.00 am. Quickly lash up the hammock with the regulation seven turns of the lashing rope, place same in the bin, shave, shower, dress, breakfast, clean up the dormitory and then parade at 8.00 am sharp. This was a breeze for me after three years of butchers’ hours.

Uniforms were not issued for a couple of days, so we paraded as a motley-looking bunch. Some recruits who had transferred from the Army and RA.A.F. were wearing their old uniforms, but soon we were all dressed as sailors with the old gear parcelled up and posted home.

A Leading Seaman (LS), quite a middle-aged man he seemed to us, was our instructor and mentor for the first two weeks. Drill, also called field exercise, went on all day. Some of the ex-army lads were good at it and they were used as examples to smarten up the rest of us. During smoko, the LS would answer our questions about various badges of rank and manual procedures. As our knowledge of things naval improved, such as the comprehensive slang terms, we began to feel like old hands very quickly. There was little contact with officers. They were god-like beings who took charge of large parades, carried out inspections and generally hardly knew a recruit existed.

For us, the Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) were our immediate authority. If necessary, through a Petty Officer, a recruit could put in a request to the Divisional Officer for such things as a leave pass if he was under 18.

To handle the ordinary problems of life such as laundry, a number of coppers and tubs were provided where some learned the hard way not to boil coloureds with whites, and socks not at all! Thieving from clothes lines was rife, so classes organised rostered watchdogs while their clothes aired.

After the first three weeks at Flinders, weekend leave was allowed every second weekend so we came to know Melbourne and its weather pretty well. My pay as an Ordinary Seaman 2nd Class (ODN – i.e. under 18) was four shillings and two pence – about 42 cents per day. At 18 as an ODI it went up to six shillings – 60 cents – no fortune but it got me by. A bed at a TocH4 cost just 10 pence (9c) per night and cheap meals were available to service personnel in subsidised places. Public transport was free to all members of the armed forces.

For good or ill during these leaves I, like many other young men away from home, learned about drinking. Perhaps it would have happened anyway, war or not, but it certainly caused me some problems for much of my life. Melbourne was full of servicemen, including Americans on leave from Guadalcanal with lots of money. There seemed to be a lot of girls about as well – it must have been a tough time for parents.

Our initial training program lasted for three months and included instruction in seamanship, torpedoes, rifle and machine guns, boat pulling and lots of field exercise. After initial training, various specialist courses could be applied for.

While our training was continuing, other things were taking place. An intake of recruits in September 1942 was allocated to something called ‘Special Service’. Rumour had it that this group was to be trained in commando tactics and become part of a unit based on the British Combined Operations – all exciting stuff to healthy young men. Several of us applied for transfer to this group believing that it would be a quick way to get into the war. However, our Divisional Officer, Lt. Dickson, rejected our requests, pointing out that our intake was Officers Training School (OTS) candidates – something that was quite strange to us and a little frightening for someone with no financial backing.

This OTS thing came as quite a surprise. We knew that it existed as it was on its fourth intake of sixty recruits per course. They were kept well apart from the rest of Flinders Naval Depot, wore white ‘tallies’ and were roundly criticised by the other groups.

Not many would volunteer for that, so groups had to be allocated to it. During the initial training period cadets were subjected to several interviews conducted by senior officers. As it turned out, the purpose was to identify potential candidates for officer training. The number of possibles was gradually reduced so that each three months a pool of sixty was available to form the next intake, divided into two watches – port and starboard. Of those sixty, only thirty would graduate to become midshipmen if under 19 years old, and sub-lieutenants if over that age.

There were plans afoot for combined operations in the islands held by the Japanese and casualties were expected to be high. Young reservist officers could do this job rather than use up the relatively small number of highly trained permanent service officers. Looking back, it can be seen that some very capable officers resulted from this mass production system.

Nearing the end of our New Entry Training, Alex Johnston, Berry Spooner and myself tried to get off the OTS list and get into the Gunnery School. The Divisional Officer blew his stack and refused our requests -perhaps too many were opting out of the OTS and numbers were hard to maintain. As it happened, Johnno failed the next board and Berry and I stayed in.

Officer Training School

The New Entry Course for 160 Class finished in mid-November and various drafts were handed out. Bluey Jamieson scored well, being drafted to HMAS Shropshire to join her in England. Most others were drafted back to their home cities for further assignment to ships or courses. It was an exciting but also regretful time as we said goodbye to good friends, hoping to run across each other as the war progressed. Berry Spooner and myself were waiting to enter the sixth course of the Officer Training School with some others from 160 Class. This we did at the end of November after a couple of weeks of doing nothing much – a fairly common situation in all the services.

Our entry into OTS was not exactly welcoming. We sixty hopefuls were paraded before the CO, Commander Harris R.N. With the help of some strong language, he told us of the impossible task he had been given – to turn us into naval officers in nine weeks. In this he intended to succeed any breach of the rules and that cadet rating was immediately out. We soon found he was as good as his word and boys were soon being weighed off for various indiscretions. For the nine weeks of the course we were confined to our school – no leave, except for Christmas.

The day started smartly at 6.00 am – stow hammocks, grab a cup of kai (cocoa) and fall in on the road by 6.10 in PT gear; a cross-country run of some miles; shower, shave, dress in rig of the day; breakfast, then clean the galley and fall in on the parade ground at 8.00 am. Cadets took turns at taking parade as they did with various duties such as stoking the boilers at night.

Most mornings, after parade, came an hour of signals exercises – morse code by Aldis lamp and semaphore by flags. This was followed by field exercises – rifle drill and marching under the guidance of Chief Petty Officer Palmer, a Whale Island Gunner’s Mate known as ‘Ming’5, for obvious reasons. For three weeks field exercises were continued for most of the forenoon, all of the afternoon watch and usually the first ‘dog watch’ – about nine hours a day. We became very good at it and impressed the Governor of Victoria who inspected us one day.

At night, we had lectures on naval history, wardroom etiquette, navigation, gunnery, torpedoes and other subjects required to magically turn us into competent naval officers.

Naval history, mainly about Lord Nelson, was pretty much a waste of taxpayers’ money and our time. Some of the older cadets – professional men, university graduates, business men in peacetime – had heated arguments with the lecturer, particularly over being kind to the defeated enemy as Lord Nelson claimed to have been (cadets who had fought in the Coral Sea battle said they had been ordered to machine gun Japanese survivors in the water, and therefore found the ‘Nelson’ type of history rather obsolete).

It was common for cadets to arise early and put in an hour or more of study before ‘Wakey, Wakey’. An exam of one kind or another was held every two weeks. The highlight of the course was a two-week cruise around Port Phillip Bay in HMAS Bingara, a converted sugar carrier. In those two weeks we practised seamanship, gunnery, signals and emergency drills such as damage control of fire, collision, enemy fire and abandon ship – this last with a lookout armed against shark attack!

As recreation, we were allowed to sail a whaler around Corio Bay, a beautiful place with the attractive town of Geelong on its shores. We were not allowed ashore but spent a great weekend sailing around the bay, greatly helped by one of our group who was an experienced yachtsman. There was so much to learn in two short weeks and we really only scratched the surface.

Back to the OTS and on with the lecture/study rounds. Just to liven us up, one day we were marched to the New Entry School and each given a class of new entries to drill. No doubt this was intended to demonstrate our power of command. Recreation was to be found in the ‘wet’ canteen -no age limit to this one – and compulsory sport at weekends. I played cricket for the first time in years and hiked several miles to a lonely, smelly beach for swimming.

With the end of the course approaching, final boards were held and we were given the choice of ‘General’ or ‘Special Services’. I chose the latter, still with a ‘gung-ho’ attitude. We drew up our own lists of passes and failures and were soon proved very wrong. Some good blokes were failed and some poor types passed. A mate of mine with a friend in the office had let me know two days early, very confidentially, that I had passed. From my observation, all Roman Catholics passed including some who were not worth feeding – I wonder why!

When the results were read out by Commander Harris, the names of those who had failed were read out first. These men immediately packed their gear and returned to New Entry School for drafting. This was 5 March 1943 and the change in our status was dramatic. Those under 19 years were now Midshipmen and those over 19 were Sub-Lieutenant naval officers, soon to receive commissions signed by the Governor General – Henry, Duke of Gloucester. We were given a sum of money and sent up to Myers in Melbourne to be measured for one blue suit and a greatcoat with suitable brass buttons. The rest of our gear we purchased from the clothing store at Flinders. That included such fancy stuff as tan gloves and half-wellington boots!

Once in our new gear people started to salute us, which was something of a culture shock at first. We spent our nights in one of the dormitories at the OTS and were allowed to visit the Gunroom or Wardroom, frequented by the permanent service at Flinders.

Notes:

- Daniel Cahill served in the Ceylon Police Force for a time and enlisted for the Boer War. Information on his service records for WWI is available through the National Archives website.

- Until 1962 rail passengers had to change trains at Albury due to different rail gauges.

- A ‘Wet’ Canteen is able to serve alcohol; a ‘Dry’ Canteen is not.

- TocH refers to hostel type accommodations called Talbot House that were established in Europe and later on in Australia during WWl to provide low-cost rest and recreation facilities for service personnel.

- ‘ Ming the Merciless’ was a character from the Flash Gordon comic strip and movies of the 1930s, a ruthless tyrant who ruled the planet Mongo.