- Author

- Bowen, L

- Subjects

- Early warships, Ship design and development

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In very early times in the Mediterranean the open and oar propelled fighting ship was the Galley. At the time of the siege of Troy the normal large Greek rowing vessel seems to have been a 50 oared boat with a single row of 25 oars on each side, but we can already see suggestions of still larger vessels, which must have had their oars arranged in some way which allowed more men to work in a given length, and it was this development which produced the bireme and began the process which led to the many-banked galleys of about 300 B.C.

Since galleys were always narrow, shallow craft, there was a very definite obstacle to increasing their length to any great extent because of the weakness of such a vessel against” hogging” or “sagging” strains tending to break it in half. Thus, the number of oars in a single simple row could not be increased very much and it became necessary to find some other method of getting greater power. It would seem the obvious course to put two or more men on each oar, but it was not until much later that the Mediterranean peoples did this.

What was done was to arrange the oars in two staggered rows, the uppermost high enough to clear the heads of the lower rowers and their greater length allowing the upper rowers to sit far enough inboard for their legs to be clear of the ends of the lower oars. Another method was to have two oars quite close together at the same level with their two rowers sitting side by side, the foremost oar of a pair being the shorter. This plan was common in medieval times and was apparently employed to some extent in classical or post classical times also, but it was the first kind of bireme from which the classical trireme, and the later many-banked galleys, were derived.

The trireme was a long vessel, a very strong, exceptionally fast and easily manoeuvred “battleship”. The ship’s driving power during a battle was the strength of the oarsmen’s muscles. The oarsmen in Greek ships were never slaves or convicts. The first Triremes appear to have been built in Corinth or Samos, most probably by the Corinthian Ameinoklis, between 650 and 610 B.C. However, their construction and use reached the highest stage of perfection in Athens with the hands and minds of the Athenians.

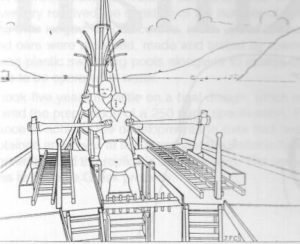

The Athenians were so proud of their triremes that whenever they were asked where they came from, they would answer, “From a place where the beautiful triremes are made”. The trireme, besides being a powerful ship, was also a thing of beauty and a real work of art. The Athenian trireme developed around the end of the 5th century B.C. (like the one that has now been built). It has been appraised as having the following characteristics – maximum length 37 metres, maximum width 5.2 metres, draught about 1.5 metres and displacement 70 tons. She was equipped with 85 oars each side (total 170) arranged in three rows, one on top of the other, requiring a rower at each oar. The top row of oarsmen was called Thranites, the middle row Zygeans and the lower row Thalamians.

The crew totalled 210-216 men and included 10 marines, 4 archers, 15 deck hands and a flautist who piped time for the rowers. The overall command of the ship was exercised by the treirarch. For sailing, a main mast with a large square sail and a smaller mast (the acations) towards the bow with a smaller sail, were employed. For steering she had 2 rudder oars, one on each side of the stern in the form of very wide oars. Its chief armament was the formidable ram on the bow. Also carried were various catapulting devices and other offensive weapons.

Under the worthy hands of the Greeks and especially the Athenians, the triremes frustrated forever Persia’s dream of world rule at the famous naval battle of Salamis, thus saving Greece and in the long run, Europe from the deadly embrace. The Salamis victory sealed for many more centuries the sovereignty of the Greeks on the sea, making the eastern Mediterranean a Greek lake. It freed the sea routes and made them safe for all merchant vessels carrying not only all kinds of material goods, but also the achievements of Greek thought, art and science, the light of Greek civilization to all the peoples of the then known world.