- Author

- Bowen, L

- Subjects

- Early warships, Ship design and development

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Over the centuries, efforts to build replicas have been documented and it is clear that until the 1980s, all efforts had failed. In fact, experts considered it couldn’t be done! The story of how it was done is intriguing. It began in April, 1982, at a dinner party in Westmorland, England, when exchanges of letters in The Times’ newspaper concerning triremes were discussed. Correspondents could not agree on the positioning of the oars and whether or not the speeds recorded by the historian Xenophon, could have been attained.

As a result of the dinner discussion. a decision was made to try and build a replica. Vital players in the project were John Coates, former head of the shipbuilding department of the British Ministry of Defence. John Morison, former Professor of Classical Studies at CambridgeUniversity and Frank Welsh, a former banker and industrialist, and also author.

The group’s initial task was to establish the hull form and layout of the oars. As much evidence as possible was gleaned from museums, ancient writings and even an Athenian dockyard inventory carved in stone, which inventory resolved the question of the number of oars and their lengths. In due course, mock ups of the hull and oars were designed, made and tested by rowers using plastic swimming pools alongside to enable the oars to be operated in water.

It took five years to settle on a final design, which required the preparation of a 250 page specification. Finance to achieve the developments to date had been obtained and it was at this stage that the Hellenic Navy agreed to build the replica in a Greek yard. The vessel was to become Greek property.

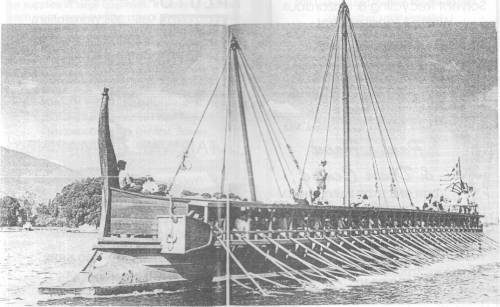

The launching took place on 26 August, 1987, into the waters of Phaleron Bay, by the Culture Minister, Melina Mercuri, who held a lantern in each hand as was the custom in ancient Athens. The vessel was named “Olympias”, the known name of a considerably earlier trireme. The designers had calculated the draught and marked the hull accordingly. After launching the draught marks were found to be accurately placed.

It was a heterogeneous crew that assembled for the trials. Men and women, slim and plump, young and old, inexperienced and experienced as oarsmen and from various walks of life, such as research scientists, policemen, GPs, QCs, etc. They had one thing in common – padded and reinforced rowing shorts. (Records show that in earlier times, rowers provided their own greased cushions).

Events had confirmed that a ship built as its designers conceived the Athenian trireme of the 5th century B.C. to have been, with 3 rows of oars of similar length, could perform much as historians had recorded. The trials showed that the ship could accelerate from a standing start to 6 knots in 30 seconds. Several measured distances of 500 metres were covered at more than 12 kilometres per hour (6.5 knots). Over a 2 kilometre stretch a speed of 9 kilometres per hour was achieved. – i.e. maximum speed under oars alone was over 7 knots, and this with a scratch crew.

Records show that the Athenians could achieve an amazing 12 knots.

Some Interesting Facts:

- The trireme carried a brass ram projecting up to 1.5 metres from the bows at sea level or below, which was the principal weapon. The ram was equipped with a smaller auxiliary ram located over it to prevent the large ram from penetrating too deeply into the hull of the struck ship and becoming stuck and unable to withdraw.

- In order to be successful at these ramming attacks, the ship had to be very fast and extremely manoeuvrable, which meant that the oarsmen had to be well trained. Even in times of peace, the ship remained at sea for six months each year, so that the crews could stay in shape. Pericles was correct in saying that the Navy required great artfulness.

- Oarsmen and crew were free citizens and not slaves as in the barbarian ships and later Roman and medieval galleys.

- Oarsmen did not all row simultaneously, but in shifts so that the voyage could go on continuously. Only during naval battles was it necessary for all oarsmen to row together in order to achieve top speed.

- The ship had some drawbacks. It could not undertake long distance voyages because it had no space for supplies in large quantities. It had to go ashore each night, carried on the crew’s shoulders, so that the crew could rest. It was a light vessel with many hull openings for the oars, so it could not withstand storms and had to stay near the coastline.

- Triremes were also referred to as Trieres.

Acknowledgments:

“Building the Trireme” by Frank Welsh.

The Greek Consulate General, Sydney.