- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

With the arrival of the new Australian Antarctic ship Nuyina at her home port of Hobart it is appropriate to look back to the beginning of our association with the vast Australian Antarctic Territory. Nuyina is a Tasmanian Aboriginal word meaning Southern Lights. The name is pronounced ‘noy-yee-nah’.

On 28 April 2016 the British company SERCO was awarded a contract for the design, build, operation and management of a new icebreaker survey and supply ship for the Australian Antarctic Division. Design and construction was outsourced to the Danish Damien Group but work on construction in Romania was suspended due to restrictions imposed by the COVID pandemic. This resulted in the ship being towed by three tugs over one month covering the 3,670 nm voyage to Damien’s shipyard at Vlissingen in the Netherlands for fitout. The total package covering design, build, and 30-year operational lifespan with maintenance is estimated at $1.9 billion. The cost of the design and construction of the ship is $528m.

After trials, under the command of Captain Gerry O’Doherty she sailed on 1 September 2021 via Cape Town, completing a 13,000 nm voyage in six weeks, arriving in Hobart on Saturday 16 October. Considering her two initial voyages Nuyina might have the distinction of a world record length for a delivery voyage. Unfortunately, the ship’s arrival celebrations were postponed as they coincided with a coronavirus lockdown in southern Tasmania.

The Australian Antarctic Territory

Antarctica is the highest, driest, coldest and windiest of the world’s continents. It comprises a vast area of about 14 million square kilometres, an area almost twice that of mainland Australia. The mysterious lands so relatively close to our own shores capture the imagination of the general public and the interest of our scientific community.

The Australian Antarctic Territory (AAT) is administered by the Australian Antarctic Division, an agency of the federal Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment. The territory’s history dates back to an 1841 British claim over Victoria Land, subsequently expanded, and in 1933 transferred by Britain to Australia. At nearly 6,000,000 km2 it is the largest portion of the Antarctic continent claimed by any nation. In addition, Australia claims an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline of the AAT’s territorial seas. Only four other countries, Britain, France, New Zealand and Norway, recognise Australia’s claim to sovereignty in Antarctica.

Australia’s connection with Antarctica stems from the explorations of Cook in determining the boundaries of a fabled Great South Land and later sealing and whaling voyages from southern Australia and New Zealand. Early explorers also wintered and replenished stocks in Australian ports. A more direct association comes from the 1911 to 1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition led by the acclaimed geologist Douglas Mawson. The first of three Australian permanent research stations based on the continent is named after Sir Douglas Mawson.

Discovery of Antarctica

The island of South Georgia is believed to be the first discovery of an Antarctic territory. It was sighted in 1675 by Antoine de la Roché, a merchant born in London of a French father and an English mother. Having acquired a 350-ton ship (name unknown) in Hamburg he obtained permission to trade with Peru in Spanish America. On the return voyage around Cape Horn tempestuous seas blew them off course until by accident they found refuge in a sheltered bay where they recovered for two weeks.

This discovery is believed to be South Georgia. La Roché eventually reached France on 29 September 1675 and wrote of his experience, which was published in 1690. Shortly afterwards cartographers started depicting La Roché Island on world maps.

A French mariner, Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier, persuaded his employers, the French East India Company, to provide him with two ships, Aigle and Marie, to explore the South Atlantic and on 1 January 1739 he discovered the sub-Antarctic Bouvet Island. The island was rediscovered by a British whaler in 1808 and in 1920 this remote outpost was claimed by Norway as a potential whaling station.

In 1700 La Roché Island was visited by the famous astronomer Edmund Halley, then undertaking a scientific expedition in command of HMS Paramore. In 1756 the Spanish vessel León also visited the island and renamed it San Pedro. Captain James Cook landed and surveyed the island and formally took possession of it on 17 January 1775 as Isle of Georgia, after King George III.

The main characteristics of the ship are:

| Designer | Knud E. Hansen | Denmark |

| Builder | Damien Group Shipyard | Galati, Romania |

| Fitout | Damien Group Shipyard | Vlissingen, Netherlands |

| Propulsion | Diesel Electric 2 x MAN engines | Germany |

| Cost – Design & Construct | AU $528m | |

| Drive | Twin controllable pitch propellers | |

| Manoeuvrability | Three bow thrusters | |

| Ice Protection | Built to break ice 1.65 m thick at 3 kts | |

| Dimensions | L 160.3 m x B 25.6 m x D 9.3 m | |

| Displacement | 25,500 tonnes | |

| Speed | Max 16 knots. Cruise 12 knots | |

| Range | 16,000 nm | |

| Complement | Crew 34 Passengers 116 | |

| Amphibious Operations | 2 Helos + 2 Landing Craft | |

| Cargo Capacity | 1,200 tonnes + 1.9 m litres fuel oil | |

| Management | SERCO for Australian Antarctic Division | British |

| Port of Registry/Flag | Hobart Tasmania | Australian Red Ensign |

Cook was the first mariner who claimed to have circumnavigated Antarctica in 1773-75 in his ships Resolution and Adventurer, followed by the Russian Bellingshausen in 1819-1821 with his ships Vostok and Mirny. Unlike Cook, Bellingshausen actually sighted the coastline of the continent.

A French expedition of 1837-1840 led by Dumont d’Urville discovered Adélie Land, which he named after his wife and claimed for France.

Lieutenant Charles Wilkes USN led an expedition in 1838-1842 which sighted many places along the coast in what is now known as Wilkes Land. The expedition called at the Fijian island of Malolo where Wilkes’s nephew and a sailor were killed while bartering for food. In retaliation a landing party destroyed villages, laid waste to their crops, and killed 87 natives. During this expedition two ships were lost and 28 crew died. On return to the United States Wilkes was court-martialled and found guilty on one charge. Some speculate that Wilkes’s obsessive behaviour and harsh code of discipline shaped Melville’s characterisation of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick. Wilkes was eventually promoted to Captain, and Rear Admiral on the retired list. Wilkes however will be remembered for naming ‘The Antarctic Continent’.

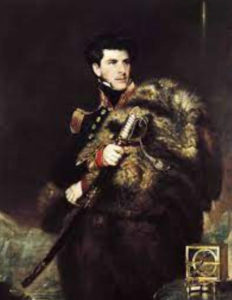

Captain James Clark Ross RN was another veteran of polar work (and incidentally said to be the most handsome man in the Royal Navy) who discovered the North Magnetic Pole. A southern voyage between 1839 and 1843 aimed at locating the position of the South Magnetic Pole, but this eluded him. Ross’s ships Erebus and Terror were strengthened and were the first to penetrate pack ice in the Ross Sea. On 27 January 1841 an Erebus lookout sighted a vast smoking mountain emitting flames and smoke. This active volcano was named Mt. Erebus and its inactive neighbour Mt. Terror. In November 1979 an Air New Zealand DC10 on a sightseeing flight with 257 persons flew into Mt. Erebus and there were no survivors. The Ross expedition named Victoria Land claiming it for the Crown and this was instrumental in British and later Australian claims over Antarctic territory.

A British scientific expedition, the Challenger Expedition, visited Antarctic waters during 1872-1876 and crossed the Antarctic Circle for the first time under steam rather than sail alone.

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897-99, under Adrien de Gerlache, was the first to spend a winter in the continent when its ship Belgica became trapped in ice. They remained hopelessly stuck, drifting with the ice and in fear their ship might be crushed, until the summer enabled the release of the ship from its icy prison.

Carstens Borchgrevink, leader of the British Antarctic Expedition 1898-1900, and his small party became the first to intentionally winter on the continent. Their ship left them there and returned the following summer.

Several other nations conducted exploration and scientific research voyages in Antarctica during the early years of the 20th century. These included Germany 1901-03, Sweden 1901-04, Britain 1901-04, Scotland 1902-04 and France 1903-05. A second French expedition 1908-10, a German expedition 1910-1912, and Japanese and Norwegian expeditions were carried out during the same period. The Ernest Shackleton expedition of 1907-09 in the ship Nimrod, with the Australians Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson, reached the South Magnetic Pole.

Having gained experience with Shackleton, Douglas Mawson went on to lead the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911-14 which claimed King George V Land and Queen Mary Land for Britain. In 1929-31 Mawson, in command of the British, Australia and New Zealand Antarctic Expedition, discovered MacRobertson Land and Princess Elizabeth Land and claimed them for Britain. Another Australian, John Rymill, led the successful British Graham Land Expedition of 1935-37.

A Norwegian, Carl Anton Larsen, returned to the Southern Ocean in 1902 in command of Antarctic carrying the Swedish South Polar Expedition. Antarctic was crushed in ice in the Weddell Sea and after many adventures the crew, including Lieutenant Maria Sobral of the Argentine Navy, and explorers were rescued by an Argentine naval ship and taken to Buenos Aires. Here they were feted as heroes and Larsen put forward his plan to establish a whaling factory. He secured financial backing and in 1904 three ships of the Compania Argentina de Pesca with prefabricated equipment from Norway arrived in the cove of Grytviken in South Georgia. As soon as the factory started production Britain demanded rent and royalties.

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition is notable as they constructed a dwelling on Laurie Island in the South Orkneys, Omond House, where in 1903 they established a metrological station. This was the first permanent structure built on the continent. In 1904 the Scottish interests were sold to the Argentine Government which began its long standing permanent residency.

Roald Amundsen of Norway, one of the most famous of the early explorers, trekked to the South Pole arriving there on 14 December 1911, to be followed by Robert Falcon Scott’s party just over a month later. After their magnificent feat Scott and his men perished on their return journey. The Amundsen/Scott expeditions captured the attention of worldwide media bringing these epic tales of endurance and hardship of heroic men to be immortalised.

The charismatic Anglo-Irishman Ernest Shackleton returned to the Antarctic in 1915-17 aiming to cross the continent. The story of his ship Endeavour being crushed in the ice and the open boat voyage with the eventual escape to South Georgia is an epic tale from an era when the world was seeking heroes to escape the tragedies of the European Great War. This expedition was helped by the Australian photographer Frank Hurley who graphically recorded important events under the most difficult circumstances.

The continent was not crossed overland until 1957-58 when parties under the New Zealander Edmund Hillary and his British counterpart Vivian Fuchs of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition crossed from the Weddell Sea and the Ross Sea by way of the South Pole.

The modern era may be said to have occurred with the introduction of mechanical equipment. This started with Scott trying motorised sledges with little success. Hillary used converted Ferguson tractors to great effect. Mawson was the first to use radio communications. Aircraft was first introduced by the Australian Hubert Wilkins in November 1928 and a year later the American Richard Byrd flew over the South Pole.

The Whaling Industry

The whale, officially a mammal, is the largest animal known to mankind with examples of the Blue Whale growing to over 30 metres long and weighing over 150 tonnes. Truly magnificent, and equivalent in size to a herd of about 30 elephants.

No discussion on Antarctica is complete without mention of the whaling industry. The hunt for seals and whales was a major reason for the initial exploration of the continent as reports of abundant stocks drew the adventurous. Sealing took place from 1786 to 1913 and was replaced by commercial whaling which began in the early 1800s. From 1904 to 1965 the production of whale oil was largely conducted ashore in South Georgia. When these stations were closed production returned to large factory ships and continued until 1982 when there was a worldwide moratorium on the killing of whales.

Herman Melville’s sea-classic, Moby Dick, written in the golden era of colonisation, delivers the following discourse: ‘Australia was given to the enlightened world by whalemen. After its first blunder-born discovery by a Dutchman, all other ships shunned those shores as pestiferously barbarous; but the whaleship touched there. The whale ship is the true mother of that now mighty colony’. Again in Moby Dick the author extols the virtue of both ships and men involved in whaling, saying: they explored seas and archipelagos where no Cook or Vancouver had ever sailed. Melville speaks with authority, having served before the mast in whaleships including, for a brief period, the Australian colonial ship Lucy Ann.

In 1823 the British sealer Captain James Weddell with his small ships Jane and Beaufoy had managed to sail further south than Cook to a new record of 74°15ʺ. Weddell also informs us that no less than 20,000 tons of sea-elephant oil had been procured for the London market and the number of fur seal skins brought from South Georgia was estimated at 1,200,000. With seals almost hunted to extinction, next came the great whale hunts with expeditions under sail mainly financed by American and British merchants. Initially the odds were reasonably evenly divided between man and beast but with the 1870s perfection by the Norwegian Svend Foyd of the harpoon gun mounted in steam powered catchers, the whale was doomed.

Captain James Ross who had sailed deep into the Weddell Sea in 1844 wrote: ‘We observed a very great number of the largest-sized black (right) whales, so tame they allowed the ship sometimes almost to touch them before they would get out of the way; so that any number of ships might procure a cargo of oil in a short time. Thus we had discovered a valuable whale-fishery well worth the attention of our enterprising merchants.’

In about 1905 whaling companies began cooperating to preserve their industry. But it was not until 1930 that the various governments became interested in this agreement and how to preserve, and if possible increase, the stock of whales. They met at Sandefiord in Norway and signed the first International Whaling Convention which constituted the International Whaling Board and arranged ‘rules’ for the annual whale hunt, introduced whale sanctions, applied quotas with limits on species, and designated whale sanctuaries. They also arranged a system for inspection and enforcement of the rules. The United States was a signatory to this convention, along with some 20 other nations including the Soviet Union.

The capital of the Southern Ocean whaling industry was the British possession of South Georgia with the first land based whaling station established by Norwegians at Grytviken in 1904. This station was operated through an Argentine enterprise Compania Argentina de Pesca which continued until 1965. In total seven whaling stations operated from South Georgia, all under leases from Britain.

With the end of shore based whaling the industry moved to large floating factory ships, some of which had been in operation from the early part of the 19th century. These could operate outside territorial waters and were much more difficult to police. By 1931 over 40 floating pelagic factories were operating and over 40,000 whales were killed. But this resulted in massive over production at the time of the Great Depression, and as a result, by the following year most of the factories were laid up, with production again ramping up in 1938.

World War and Whale Oil Production

At the outbreak of WWI, Norway, recently independent from Sweden and with only 2.5 million inhabitants, mostly involved in farming and fishing, and with a large merchant fleet, sought to remain neutral. However, this quasi-neutrality was dependent upon Britain’s control of sea lanes through the North Sea. The use of Norwegian ships and the production of whale oil was important to the British war effort and the Norwegians were encouraged to expand these enterprises with almost their total whale catch going to British interests at artificially low prices. Between 1914 and 1917 over 175,000 whales were killed in the Southern Ocean with their products strategically important to British arms production.

A common use of whale oil was making soap with a by-product glycerine. Nitrate glycerine is a key component in the production of cordite used in the production of artillery and naval shells and small arms ammunition. Whale oil was also used in making high grade lubricants that did not corrode metals and remained liquid in freezing temperatures.

During WWII production of whale oil was greatly reduced with only one factory remaining in operation. When production increased from 1946 the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established by interested nations to administer regulations for the conservation of stocks.

In 1947 Argentina sought to boost its presence in international whaling and ordered the world’s largest whale factory ship from the British yard Harland & Wolff, to be complemented by 14 whale catchers built in Britain and Japan. In 1948 Alfredo Ryan, the chairman of the company, visited London and held discussions with British officials on the sale of the Falkland Islands to Argentina. But within a year the company had run into financial difficulties and had to be bailed out. Who better to assist than the Greek born Argentine citizen Aristotle Onassis and his Olympic Whaling Company operating under the Panamanian flag?

In the 1950s about 12,000 men went down to the Southern Ocean each year to hunt the whale. Of the whaling expeditions annually proceeding to these regions the majority were Norwegian. Other countries participating were Britain (3) Japan (2) and one apiece from South Africa, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union and Panama. By 1960 the glory days diminished as mineral substitutes took over from whale oil leading to falling prices and a drastic decline in production.

Mounting public pressure against whaling in 1972 caused the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment at a meeting in Stockholm to recommend a ten-year ban on whaling. As a result, the International Whaling Commission in 1982 decided there should be a pause in commercial whaling of all species from the 1985/86 season. With a few minor exceptions this moratorium remains in place to this day.

Territorial Claims

Territorial claims on the Antarctic are emotive and open to interpretation. Some go back as far as the 1493 Treaty of Tordesillas where Pope Alexander VI divided the New World between competing Portuguese and Spanish spheres of influence. Chile has evoked this ancient treaty over its claim for jurisdictions over sectors of Antarctica and her neighbour Argentina has also evoked the treaty in favour of its claims over the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

The Argentine Government claimed sovereignty over South Georgia in 1927 and the South Sandwich Islands in 1938. Argentina also operated a naval and research station on Thule Island in the South Sandwich Islands from 1976 to 1982. The Argentine claims contributed to the 1982 Falklands War.

Seven countries have made territorial claims in Antarctica; they are Argentina, Australia, Britain, Chile, France, New Zealand and Norway. These countries have tended to place their Antarctic scientific observation and study facilities within their respective claimed territories; however, a number of such facilities are located outside of the area claimed by their respective countries of operation, and countries without claims such as China, India, Italy, Russia, Pakistan, Ukraine and the United States have constructed research facilities within the areas claimed by other countries.

There are a number of overlapping claims and 1,610,000 km2 known as Marie Byrd Land is unclaimed.

| Territory | Claimant | Date | Area km2 |

| Adélie Land | France | 1840 | 432,000 |

| Argentine Antarctica | Argentina | 1932 | 1,461,597 |

| Australian Antarctic Territory | Australia | 1933 | 5,896,500 |

| British Antarctic Territory | Britain | 1908 | 1,709,400 |

| Chilean Antarctic Territory | Chile | 1940 | 1,250,258 |

| Peter Island | Norway | 1931 | 154 |

| Queen Maud Land | Norway | 1939 | 2,700,000 |

| Ross Dependency | New Zealand | 1923 | 450,000 |

| Total | 13,899,909 |

Australian Antarctic Research Stations

In 1947 the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) was formed to set up research stations on the sub-Antarctic islands of Heard and Macquarie, and examine the possibility of a station on the Antarctic mainland. Heard Island was manned continuously from December 1947 to March 1955 and Macquarie Island has been continuously manned from March 1948.

The first permanent Australian station on Antarctica was established at Mawson in February 1954, and a second station at Davis in January 1957. Captain John Davis was second in command to Mawson and master of Aurora and Discovery, the ships used in Mawson’s two expeditions. Davis was closed from early 1965 to early 1969 but now continues to support scientific research.

In the 1957-58 International Geophysical Year many nations mounted special expeditions to Antarctica, making observations and pooling their resources. The Americans set up seven stations, one named Wilkes after the naval officer named earlier in this paper. In 1959 the United States passed control of this station to Australia. Wilkes was manned until February 1969 when it was closed in favour of a newly built facility just two miles distant. This new station was named Casey after the popular Australian Governor-General.

In the summer of 1975-76 members of ANARE working from a base camp in Enderby Land came across a cairn beneath which was a metal cylinder containing the proclamation placed there by Douglas Mawson’s British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929-1931. Mawson’s party claimed the area for the British Crown.

Mawson’s BANZARE and his earlier Australian Antarctic Expedition 1911-14 were responsible for discovering the vast portion of the Antarctic coastline to become known as the Australian Antarctic Territory over an area of approximately 6,000,000 km2 which represents about 40 percent of the entire continent. The Antarctic Territory was handed from Britain to Australia and came under the authority of the latter with the passing of the Australian Territory Acceptance Act on 13 June 1933.

Under the terms of the Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory, it is agreed that nothing in the Treaty will be taken to mean that any nation which has claimed territory in Antarctica gives up its claims, nor that all nations necessarily recognise these claims.

The International Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic Treaty was signed in Washington DC on 1 December 1959 by the twelve nations who were active in scientific research on the continent. It came into force on 23 June 1961 for a period of thirty years. It has been reaffirmed since then and many other nations have become party to the Treaty which now stands at 54 members. Since 2004 a permanent Secretariat has been established which is located in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Summary

The arrival of the new survey ship Nuyina marks the opening of a new chapter in Australia’s involvement in Antarctica. This purpose-built ship allows greater levels of access and support to our most remote research stations and through their combined endeavours greater levels of knowledge will be gained into what lies beyond one of the world’s last frontiers.

References:

Chipman, Elizabeth, Australians in The Frozen South, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1978.

Dakin, W.J., Whalemen Adventurers, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1938.

Fitzsimons, Peter, Mawson and the Ice Men of the Heroic Age, William Heinemann, Sydney, 2011.

Headland, Robert, The Island of South Georgia, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Melville, Herman, Moby-Dick, Harper Brothers, New York, 1851.

Robertson, R.B., Of Whales and Men, MacMillan & Co, London, 1956.