- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Geoff Barnes

The author, a keen amateur historian and model maker, gathered most of the information used in this article from research undertaken in building a diorama of the Gallipoli landings for the Australian National Maritime Museum.

This year a great amount of Australian media and money was dedicated to commemoration of the ANZAC landing on 25th April 1915. There will probably be much less attention paid in December 2015 to the Allies’ departure from Turkey’s shores, a retreat usually tactfully referred to as a ‘withdrawal’. Neither will there be much said about who got the men ashore in the first place, and got them off again. And how they did it!

Our mythic image of Gallipoli is centred on the Australians (and when we remember to mention them, the New Zealanders) at Anzac Cove, but we tend to overlook the fact that the Anzacs were an untried resource making up numbers, supporting the more reliable British troops in a campaign that was itself a sideshow that escalated.

The Year 1915

In the year 1915 the Western Front was deadlocked. Russia was in danger on the Eastern Front, and demanding assistance. Without Russia as an ally, the weary British War Council felt that Britain and France would have little hope of defeating Germany. What to do as an adequate demonstration of good faith to Russia? Winston Churchill, First Sea Lord of the Admiralty, always ready with a lateral idea, had already proposed a naval attack on the Dardanelles with some aging battleships that could be spared from the main arena of operations. Now he re-sold the idea.

It was a gamble but if it succeeded it could topple the shaky Turkish government. If it failed, the fleet could withdraw without losing too much British prestige, having made the demonstration requested by Russia. In crisis and with no other viable options on offer, the War Council agreed.

A Low Cost Campaign

The Gallipoli Campaign was always intended to be a low-cost naval campaign. Lord Kitchener, the much-revered and feared British Secretary of War, was reluctant to commit ground forces away from the main game but the War Council was warming to this break-out option.

General Sir Ian Hamilton was currently responsible for the defence of England and was surprised when he was summoned at short notice to meet with Kitchener. Hamilton was a proven combat veteran, a soldier-poet and intellectual – unusual among his fellow generals – but a bit of a ditherer and a devoted disciple of Kitchener unwilling to offend The Great Man. Hamilton knew nothing of Churchill’s proposed adventure, only to discover that he was to command a force roughly 78,000 strong, consisting of the British 29th Division (which he would return to England as soon as it could be spared), the Royal Naval Division, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps currently under training in Egypt, and a French contingent of mainly colonial troops about a division in size.

Staff Work

Armed services exist to further civil policies that cannot be furthered by any other means. It does this by force or threat of force, and in a democracy, this force will be sanctioned by the people’s representatives. Any army is a huge and incredibly complicated machine, and if it is to function properly, with all parts contributing to the common cause, it needs a chain of command that starts with the War Council deciding to ‘Take the Dardanelles’ and a couple of hundred links down that chain, a fresh-faced young Digger wades ashore supplied with a couple of days’ rations, water and enough ammunition. This fighting sharp-end will need many, many Services to guarantee that he gets ashore; supply of everything, transport to move it, yet more transport to move the primary transport, field medical and hospitals, ordinance, engineers to make and repair and fix things, prior intelligence about the landscape and the enemy, a means of updating that intelligence, legal, pay, chaplains, graves registration, salvage, police, hygiene and sanitation…and on and on. And each element has to be organised, and meshed to meet the schedules, supply chains and shortcomings of the other elements. The commanders decide what is to be achieved, the Services do the many jobs, and the Staff co-ordinate the whole and prepare the detailed instructions to ensure that everything happens as it should. In theory when two armed services are involved in a campaign, especially when they are the British Army and the Royal Navy, each with a long tradition of doing it their own individual way, and with substantial egos at senior levels, the campaign will be a steep learning curve for all involved.

The Never-Intended Invasion

Kitchener was not willing to dilute his forces committed to the main game – the Western Front. Hamilton’s task was to support naval operations in the Dardanelles. He had too few troops and resources to attempt a full-scale invasion. His forces were intended to control the Peninsula once the naval forces had silenced the Turkish coastal defences with their heavy guns, then join with the Russians in a joint land-naval operation and attack Constantinople.

In February 1915 the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet sailed into the Straits, bound for the Sea of Marmora, only to find that the confined space of the Narrows meant that they were too close to the enemy. The flat trajectory of its naval gunfire could not destroy the Turkish fixed gun emplacements and the agile Turkish horse artillery proved a real problem at close range. The Fleet failed to break through and, having given the Turks a clear indication of a possible Allied invasion, temporarily withdrew.

No Precedent for Such a Campaign

Hamilton was now faced with the possibility of realising an under-resourced task of neutralising the Turkish batteries from the land. Two months later, on 17th March, he arrived on board HMS Phaeton to inspect the hostile coast. Maps and intelligence were vague and inadequate, and aerial reconnaissance was as yet in its infancy. He joined the naval commander, Vice Admiral de Robeck, who had just replaced the previous commander who had gone home sick, and who was equally new to the situation. On the 18th Hamilton watched at first hand the Fleet’s determined efforts to force the Dardanelles unaided. Sixteen warships swept into the Narrows, unaware that the Turks had hastily mined them on the previous evening. Three battleships were sunk, two severely damaged, and one was beached.

The essence of the dilemma was now obvious; the naval assault could not prevail because the Turkish guns could not be silenced until the mine fields were cleared, but the minefields could not be cleared until the guns were silenced.

Urgency pre-empts Planning

Hamilton and de Robeck were convinced that further naval attacks would have to wait until ground forces could assist. Ironically, they were unaware that the Turks were almost out of ammunition and mines, but now the Turks, with the able leadership of the German Generalleutnant Otto Liman von Sanders, proceeded to reinforce, re-organise and re-supply their forces in the Dardanelles.

The War Council, alarmed at the Fleet’s failure, now wanted ‘urgent action’, and Hamilton had to prepare for an amphibious invasion of a strongly defended and well-prepared foreign shore in a perilously short time scale, with poor intelligence, and in the face of high tech weaponry, mounted against an enemy with a long and glorious military past, committed to defending its homeland. In size, complexity and ill-grounded optimism, it was a campaign that was unprecedented in military history.

The advantage of an amphibious landing was the Turks had to defend the whole coastline, unsure where British would strike, and that the Fleet could provide powerful and flexible fire support. Naval firepower was essential, as this secondary campaign was never adequately equipped with shore-based artillery, but all too often the fighting inland precluded such support.

A Very Tight Schedule

So 75,000 men, 1,600 horses, donkeys and mules and 600 vehicles with attendant supplies were scattered at various garrisons, camps and warehouses all around the eastern Mediterranean, and had to be assembled, loaded, and transported to the harbour of Mudros on the nearby islands of Lemnos, and then on D-day be landed under direct enemy fire. All to be conducted in a matter of less than two months, with no manuals or body of informed experience to consult.

‘It is a matter of some surprise that the expedition ever got to sea at all’, writes Alan Moorehead in his definitive account of the campaign. ‘On March 26 Hamilton’s administrative staff had still not arrived from England (it did not get to Alexandria until April 11), many of the soldiers were still at sea, no accurate maps existed, there was no reliable information about the enemy, no plan had yet been made, and no one had yet decided where the Army was to be put ashore. The simplest of questions were unanswered. Was there water ashore or not? What roads existed? What casualties were to be expected and how were the wounded to be got off to the hospital ships? Were they to fight in trenches or in the open, and what sorts of weapons were required? What was the depth of water off the beaches and what sort of boats were needed to get the men, the guns and the stores ashore? Would the Turks resist or would they break as they had done at Sarikamish; and if so how were the Allies to pursue them without transport?’

Hectic improvisation occurred as young Staff officers cleaned out the Alexandria bookshops of any guide-books with maps. The bazaars in Cairo were stripped of anything that could hold water, like goatskins, oil drums and kerosene tins. Ordnance workshops were flat out manufacturing trench periscopes and improvising hand grenades. Donkeys and their native drivers were recruited but it was decided that the Australian Light Horse would be leaving their mounts back in Alexandria until the Turks were retreating, and only then would they be shipped to Gallipoli, be re-united with their troopers, and ride triumphantly into Constantinople.

Co-ordination

Hamilton was aware of the high risks involved, so dependent on co-ordination between two temperamentally very different armed forces – the Army and the Navy – and on the ever-variable weather. It was only a half-century ago that the calamitous landings in the Crimea had taken place at Kalamatia Bay.

But gradually scepticism among the Staff was replaced with optimism under Hamilton’s quiet assurance. He trusted his Staff to get the job done. This trust, and his lack of direct supervision, sowed the seeds for the failure of the bold idea. In Hamilton’s first despatch, composed a month after the landings on 25th April, he wrote: ‘As so often happens in war, the actual course of events did not quite correspond with the intentions of the Commander.’

Going to War by Sea

A land campaign has the advantage, even luxury, of lines of communication. The Turks could re-supply direct by road or rail from Constantinople. The invading force was totally reliant on the sea. If anything was overlooked, it was a matter of weeks at sea to the home ports and back again. At the campaign peak more than two hundred and fifty French and British warships were involved, but these paled in the face of the merchant fleet that supported the Allied troops. ‘From a technical point of view’, wrote Hamilton to his superiors in London, ‘it is interesting to note that my Administrative staff had not reached Mudros (assembly point on an island close to the peninsula) by the time when the landings were first arranged. All the highly elaborate work involved in the landings were put through by my General Staff working in collaboration with the Naval Transport Officers allocated…Navy and Army carried out these combined duties with the perfect harmony which was indeed absolutely essential to success.’

In the 19th century, ships’ boats were sufficient to land marines and light infantry in distant colonial conflicts, but this war was using rapid fire weapons, high-powered artillery and even aircraft. Destroyers could tow Navy steam pinnaces and motor lighters plucked from the warships. These in turn could tow auxiliary ships’ lifeboats filled with troops, but eventually navy crewmen would have to row them to the shoreline in full view of the enemy.

‘Nothing but a thorough and systematic scheme for flinging the whole of my troops under my command very rapidly ashore could be expected to meet with success; whereas, on the other hand, a tentative or piecemeal programme was bound to lead to disaster. The landing of an army upon the theatre of operations I have described – a theatre strongly garrisoned throughout, and prepared for any such attempt – involved difficulties for which no precedent was forthcoming except possibly in the sinister Legends of Xerxes. The beaches were either so well defended by works or guns, or else so restricted by nature that it did not seem possible, even by two or three simultaneous landings, to pass troops ashore quickly enough to enable them to maintain themselves against rapid concentration and counter attack which the enemy was bound in such case to attempt. The first of these necessities involved another unavoidable if awkward contingency, the separation by considerable intervals of the force.’

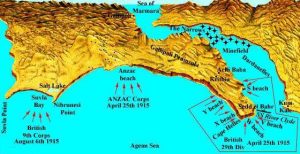

Going Ashore

Hamilton’s plan was elegant but did not leave room for contingency. The British Division, the 29th, would land on the beaches at Cape Hellas at the bottom of the Gallipoli peninsular, and move quickly to capture the key high point of Achi Baba. There would be five landings in all, each on small beaches because there was no single beach that would allow for an overwhelming ‘hammer blow’. The Anzacs would land in the north and attack the heights of Chunuk Bair. Another feint would be made at the European neck of the Peninsula, at Bulair, and the French would attack at Kum Kale, on the Asiatic shore of the Dardanelles. The Turks would not know which was the main assault until it was too late, and the 29th and the Anzacs would join up in a pincer movement to complete the victory.

Hamilton had wanted to land at night but the Navy, fearing uncharted rocks and tricky currents, insisted on daylight. The invasion was planned for 23rd April but poor weather delayed it until 25th.

‘A simple plan but flawed’, write Fred and Elizabeth Brenchly in their book about the AE2’s exploits, Stoker’s Submarine. ‘Historians have flayed the Gallipoli campaign for poor leadership, inaccurate maps, lack of coordination between army and navy, the somewhat cavalier approach to planning and underestimation of the Turkish forces…The 29th Division, landing at Hellas Point, found some virtually uncontested and others death traps.’

The merchant ship River Clyde was an example of untried experimental technology. This converted freighter was run aground at V Beach, concealed hatches in the bow flew open, and troops poured out of the protective hull, down ramps and on to the beach – an innovative idea but one that would prove fatal in the face of intense Turkish fire, and result in over twelve hundred casualties.

The Turks were thinly spread across a wide coastline. At X and S Beaches the British dug in with little interference, but at W Beach the troops were slaughtered as they waded ashore from the ships’ boats. The Anzacs were the only troops to land pre-dawn, and they were landed at the wrong place, and suffered severely as they tried to scale the poorly charted heights.

The morning’s confidence was replaced with confusion. The invasion was becoming bogged down on the narrow beaches and the beleaguered troops were advised by Hamilton to ‘dig, dig, dig’. The Turks were much better organised than anticipated. They regrouped and reinforced rapidly, but their general offensive on 28th April, intended to drive the invaders into the sea, was stopped in its tracks by the Navy. A battleship’s 15-inch shrapnel shell contained the equivalent of 15,000 bullets and such devastating effects early in the campaign caused the Turks to re-think their mass charges across open ground. The breakout was starting to look a lot like the Western Front, and would change little over the months to come as both sides faced each other in a stalemate.

Everything Must Come By Sea

Because there were no suitable arrangements for transferring men and cargo directly on to the beaches, Thames tug boats sailed for Cairo, towing domestic barges that had previously been used to unload cargos in the ports of England. The cargo ships would have to unload from their often ill-packed or illogically stacked holds. Every box, water can, horse, mule, motor truck, bicycle, wheelbarrow, mail bag and artillery shell had to be manhandled into these barges and rely on the work-horse naval steam pinnaces to tow them ashore. Many a young midshipman earned his spurs on these hazardous transits, the youngest was aged 13. The RAN Bridging Train was constantly repairing the makeshift jetties at Suvla Bay after their inadvertent or over-enthusiastic approaches.

The return journeys were frequently filled with wounded, and the hospital ships were desperately overcrowded. Barges full of badly wounded and severely dehydrated men were taken from vessel to vessel and were refused permission to winch their cargo on board.

Many of these vessels were ocean liners and merchant vessels that had been converted in a matter of weeks, even days. The Arcadian, previously a pleasure cruiser to the Norwegian fjords, was fitted out as Hamilton’s headquarters ship. The P & O liner Berrima is one small example. It had been taken over by the Australian government and converted to an expeditionary ship in 1914 to carry the Australian Military Expeditionary Force to New Guinea. On its return to Sydney, it was refitted with an enlarged hospital, improved troop and officer accommodation, and more toilets. It sailed for the Middle East in December 1914 with the second convoy carrying Anzac troops, and towing the submarine AE2.Berrimawas the first of some seventy conversions of Australian-based merchant ships for military purposes.

Deep draught cargo ships could not approach the shallow beaches. This meant that they were out of the range of the Turkish shore-based artillery, although there was a constant fear of submarines. Life aboard seemed surreal, however, to a young Anzac officer fresh from the flies, appalling rations and filth ashore. He was amazed at the starched table cloths, stewards and three-course meals on board one of the command vessels.

Short Supply

When reading Hamilton’s despatches, it becomes obvious from the outset that water was a primary problem. The August attempt for a grand breakout highlighted the problems of everything having to be carried across the sea to Gallipoli. ‘As to water, the element of itself was responsible for a whole chapter of preparations. An enormous quantity had to be collected secretly, and as secretly stowed away at Anzac, where a high-level reservoir had to be built…a stationary engine was brought over from Egypt to fill that reservoir. Petroleum tins….were got together and fixed up with handles….. but the collision of the Moorgate with another vessel delayed the arrival of large numbers of these just as a breakdown in the stationary engine upset for a while the well-laid plan of the high-level reservoir. But Anzac was ever resourceful in the face of misadventures, and when the inevitable accidents arose it was not with folded hands that they were met.’

There were shortages of everything – transport, guns, ammunition, preserved food, aircraft and men – but Hamilton was not surprised that appeals were met with terse replies or silence. He had promised not to ’embarrass’ Kitchener with requests. De Robeck was equally wary as his requests would have to go via the equally peppery Admiral Jacky Fisher in the Admiralty. Churchill would have helped as it was his idea, but he had fallen out with this prickly First Lord. Reputations and careers were at stake.

Black Beetles

Fisher, ‘Father of the Dreadnought’ and hyper-active one-man think tank of the Royal Navy, had been loudly critical when the Dardanelles campaign was conceived as an essentially naval exploit, with army support if required. He was convinced that the troops on shore would be essential.

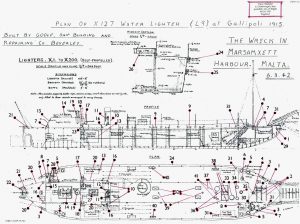

In February, when Fisher had seen the Fleet suffer its first reverses and as the need for an amphibious landing capacity became more apparent, an order was sent by the Admiralty to Pollock and Sons shipyard in Kent to design and oversee the construction of two hundred landing craft for the Gallipoli campaign. In just four days Walter Pollock drew up plans for long motor-driven barges with spoon shaped bows that could be easily run up on to beaches, and equipped with drop-down ramps to facilitate unloading. These displaced 135 tons, and were 105 feet long, 21 feet wide and 7 foot 6inches deep. They were powered with heavy oil when available, and were called ‘X’ lighters. They were not ready for the initial landings, however, but were later towed to the Aegean and went ashore in the Suvla Bay landings on 6th August. The ‘X’ craft were quickly named ‘black beetles’ due to the stag-horn beetle-like derricks that supported the ramps.

Learning the Hard Way

Gradually, lessons were learned. The Army and the Navy discovered how to live with each other’s egos and priorities. ‘Only because of allied naval supremacy could this expedition be contemplated’, writes Dr David Stephens, ‘and after the landings the navies focussed on the direct support of troops ashore and ensuring the flow of reinforcements exceeded that of the enemy…While seldom recalled today, the level of Army and Navy cooperation eventually attained at Gallipoli was far ahead of anything contemplated before the war…New and unproven technologies proliferated. Planning for the close integration of land, sea and air assets had not been undertaken before, and original solutions even included the first steps towards force networking’.

Shipboard communications were by radio, and reasonably effective, but ashore telephone lines were frequently cut or non-existent. Naval balloons and the few aircraft promised highly accurate and responsive fire to the commanders ashore, but in reality the rugged landscape, the distance between gun platform and target, the dust and haze, and the hidden enemy positions meant that much of the firing was prearranged, inflexible, and often fatal to the friendly forces, and semaphore flags were often the only way to communicate with the seaborne gun platforms.

However, Allied sea power was instrumental in disrupting the Turkish lines of communication. After the stalled initial landings, with General Birdwood on Anzac beach surrounded by dead and wounded, and appealing to be evacuated, it may well have been the limited success of the RAN submarine AE2 that put heart back into Hamilton and his staff, and the decision was made to persevere. No matter that AE2was scuttled in the Sea of Marmora two days later; the die was cast.

Insert photo: Sketch plan of Black Beetle kindly provided by David Mallard based on a wreck abandoned at Malta after the withdrawal.

As the campaign progressed, the battleships and monitors shelled the rail and road links to Constantinople and together with the gallant actions of other British submarines, the Navy delivered one of the few undisputed successes in denying sea access to the Turkish reinforcements.

Hamilton Takes the Blame

The campaign was a disaster, Hamilton was sacked. After a stalemated nine months the Allies evacuated, leaving Turkey victorious. The RAN Bridging Train played a final useful role at ill-fated Suvla Bay, creating some of the wharves for the best-managed part of the entire campaign – the retreat.

Hamilton had been given an extraordinary task to perform, and was never adequately equipped to achieve it, but he had proven unwilling to supervise, both during the planning and execution phases, and therefore was not able to reassess when things went sour and when his commanders, most of them second-rate and unimaginative, needed clear leadership. The whole campaign was a gamble but he failed to develop contingency plans, he was over-confident, his objectives were too ambitious, and he under-estimated his enemy. He was also too concerned with not upsetting Kitchener. And the lack of precedent for an amphibious invasion of this magnitude and complexity proved fatal.

Epilogue

The humiliation of the Dardanelles campaign was so bitter to the British government and armed services alike that after World War I no concept of amphibious operations was to be reconsidered. However, when the Italians attacked Abyssinia in 1935, an intervention from the Red Sea was contemplated. The bitter lessons of Gallipoli were dragged out of the cupboard. Then Japan attacked Tientsin using four hundred barges packed with troops. The forward planners of British Admiralty paid attention and in the summer of 1938 they finally obtained the go-ahead to create a combined services structure to study the possibility of amphibious operations.

Neither Napoleon nor Hitler were willing to commit to an amphibious invasion of Britain without control of the Channel, and after Dunkirk the British, now isolated, protected by these waters but equally isolated by them, realised that decisive operations on the continent would have to be essentially mounted from the sea.

A fleet of specially designed ships would be necessary to successfully land large armies on enemy soil. At the core was the need for shallow draft vessels that could run safely into a beach then pull back again to be re-used after discharging their cargos of men and material, with drop-down ramps on their bows. The ghosts of ‘black beetles’ and the River Clydereappeared.

Three types were progressively developed. There would be small landing craft that could be transported to the zone of operations on the decks of larger craft. There would be larger landing barges that could sail under their own power for short trips and which could carry larger cargos and vehicles, but which would still be carried on larger ships for longer passages. There would be ocean-going ships over sixty meters long to do the bulk transport. The fire support of battleships would still be essential but these would be supplemented in time by smaller purpose-built shore bombardment vessels, and increasingly effective air support. And most essential, there would be a Combined Operations formation to coordinate the contributions of the navy, army and air force, with clear objectives freed from inter-service rivalries.

Dr David Stevens has this final comment: ‘The lasting legacy of Gallipoli should not be seen in terms of the slaughter in the trenches. Though ultimately a failure, the campaign provided a wealth of shared experience. Joint operations techniques and procedures, ranging from improved command and control through to common terminology were learned the hard way in 1915. But the campaign paved the way for the succession of amphibious assaults that brought victory in 1945. The lessons of both success and failure in the campaign informed the development of amphibious tactics and equipment between the wars. The fundamentals of modern maritime power projection were established.’

Note: General Sir Ian Hamilton’sreference to the ‘Legends of Xerxes’ relates to Xerxes I (519-465 BC) a notable King of Persia who crossed the Hellespont (Dardanelles) and thereby invaded Greece.

Bibliography

Brenchley, Fred and Elizabeth, Stoker’s Submarine, Melbourne: ATOM, 2014.

Gaujac, Paul, Dragoon: Amphibious Operations in World War II, Paris: Histoire and Collections, 2004.

Grehan, John and Mace, Martin, Editors, Despatches from the Front: Gallipoli and the Dardanelles 1915-1916,Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2014.

Jeremy, John, LHD and LSD-The Evolution of Australia’s New Amphibious Ships, text of PowerPoint lecture, Sydney, 2015.

Laffin, John, Damn the Dardanelles, London: Osprey, 1980.

Masters, John, The Road Past Mandalay, London: Cassell, 2002.

Moorehead, Alan, Gallipoli, London: Macmillan, 1975.

Spofford, Major C. R., Planning the Gallipoli Amphibious Landings: an operational Analysis, paper submitted to Faculty of the Naval War College, Newport, N.J., 1994.

Stevens, Dr David, Gallipoli as a Joint Maritime Campaign, accessed 2 October 2015, http://www.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/gallipoli-joint-maritimr-campaign.