- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship design and development, History - WW2, Naval Engagements, Operations and Capabilities

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Andreas Biermann

Introduction

This article is the first of two that aim to provide a new perspective on the Battle of Cape Spada on 19 July 1940, one of the first major naval engagements of the Royal Australian Navy in the Mediterranean in the Second World War. On 19 July 1940, at Cape Spada on Crete’s northern coast, the light cruiser HMAS Sydney, leading a force of five Royal Navy destroyers, engaged the two light cruisers of the Regia Marina’s 2nd Cruiser Division, sinking RN Bartolomeo Colleoni.

The articles will provide the Italian perspective of this battle, starting with background on the genesis, characteristics and employment of the initial post-First World War Italian light cruiser force, the 1920s di Giussano-class cruisers, in the run-up to the Second World War in the Mediterranean. The second article will describe the battle in detail. The design considerations and weakness of ships of the di Giussano class are critical in understanding the decision-making of the Italian commander and the outcome of the battle.

The Genesis of the Regia Marina’s Light Cruiser Force – 1928 to 1940

The First World war had not seen an urgent need for a traditional cruiser force in the Regia Marina, as the key struggle was with the Austro-Hungarian navy in the Adriatic, and the role of the cruiser was covered by the light scouts of the Mirabello and Aquila classes. At the end of the war the Regia Marina’s scout or light cruiser force, called Esploratori, consisted only of four obsolete pre-First World War designs, the protected cruiser Libia, the scout cruiser Quarto and the two scout cruisers of the Nino Bixio class, dating back to 1907, 1909 and 1911 respectively.

These vessels were successively decommissioned between 1927 and 1939. From 1921 onwards, reinforcing them were five scout cruisers received as war reparations from Germany and Austria-Hungary which were renamed after Italian port cities, Ancona, Bari and Taranto for the three German vessels and Brindisi and Venezia for the Austro-Hungarian vessels. They were comprehensively modernised before entering service.

After the First World War a rapidly developing naval arms race in the Mediterranean put pressure on Italy to create a modern cruiser force and in consequence, from 1926 onwards the Regia Marina began a construction program for a class of 12 fast, well-armed but lightly armoured scout cruisers, still referred to as Esploratori at this time. These vessels became what is often referred to as the Condottieri-class of 12 light cruisers, even though they were not really a single class. The 12 Condotierri were laid down in five sub-classes, the design conceptualisation of which evolved over almost a decade. The final vessels of the Abruzzi sub-class reached almost twice the size of the initial di Giussano sub-class and followed a completely different design concept.

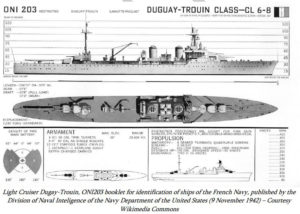

The design requirement for this new class was based on the presumption that the most likely confrontation the Regia Marina would face in the western and central Mediterranean was a struggle for supremacy with the French Marine Nationale. In the early 1920s, the Marine Nationale had radically modernised the design concept of the scout cruiser with the design and introduction in 1926 of the Duguay-Trouin class. These were fast, practically unprotected vessels of 7,250 tons displacement armed with long-range 6” guns, carrying a scout plane launched from a catapult. Conceptually thethree Duguay-Trouin class cruisers were another step towards prioritising speed and gunfire over protection, as the idea was that they could outgun and outrange destroyers, while being able outrun any heavier vessel that could harm them. Their introduction was accompanied by the launch of the super-heavy destroyers of the Chacal and Guepard classes. These in turn were a reaction to the Regia Marina’s new heavy destroyers of the Leone class and incorporated design aspects of the late-First World War German destroyers of the Großes Torpedoboot 1916 class, which had conceptualised the heavily armed and fast destroyer model and of which SMS S113 had been ceded to France after the war. The Chacals and Guepards carried a main armament of five single 130 mm/5.1” guns on the Chacals or 139 mm/5.4” guns on the Guepards and were capable of exceeding 35 knots design speed. They were thus considerably better armed and faster than most other destroyers of their time.

The combination of the Duguay-Trouin cruisers with the super-destroyers created a fast and well-armed, if lightly protected, strike force, to which the 12 Esploratori were the Regia Marina’s response. The initial concept of employment for this new Regia Marina Esploratori force, embodied in Colleoni’s motto Velocemente e veemente (Fast and Forceful), was thus to conduct rapid raids in the western Mediterranean, interdicting the sea lanes between metropolitan France and its North African colonies. In line with the propaganda efforts by the Fascist regime, which tried to hark back to Italy’s martial past, the new Esploratori were given names of famous Italian military commanders, or Condotierri.

The 12 Esploratori were to be accompanied by 24 Esploratori Leggeri or light scouts, of the Navigatori class, named after famous Italian seafarers. These were essentially large fast destroyers. They displaced 1,628 tons and were equipped with six 120 mm/4.7” guns in three twin turrets as their main armament. In the case of confrontation with France, raiding squadrons composed of Esploratori divisions with Esploratori Leggeri flotillas in support would sail from bases on the Italian west coast, as well as in Sardinia and Sicily, searching for and destroying French convoys and/or chasing French raiders intruding into the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas, threatening Italian traffic. This operational concept did not change substantially until the mid-1930s, when the final sub-class of the Condotierri was laid down. The Battle of Cape Spada was triggered by such a cruiser raiding operation. By the mid-1930s the Royal Navy had become the major concern for the Regia Marina and the last of the Condotierris were vastly different types of ships.

| Vessel | Patron | Laid down/completed | Fate |

| Alberto di Giussano | 12th century military leader of the Italian Lega Lombarda alliance against German Emperor Barbarossa | 1928/1931 | Lost 1941 |

| Alberico da Barbiano | 14th century mercenary leader | 1928/1931 | Lost 1941 |

| Giovanni delle Banda Nere | 16th century mercenary leader | 1928/1931 | Lost 1941 |

| Bartolomeo Colleoni | 15th century army leader | 1928/1932 | Lost 1940 |

The First of the Condotierri Class

The initial plan of the Regia Marina was to build 12 Esploratori of the design of the di Giussano sub-class. Nevertheless, after completing the first two, Alberto di Giussano and Giovanni delle Bande Nere, the financial crises of 1929 caused budget cuts which reduced theTable 1: Overview of the di Giussano sub-class planned programme of 12 to only four, while the programme for the accompanying Esploratori Leggeri was cut from 24 to 12. The two other vessels completed to the same design were Bartolomeo Colleoni and Alberico di Barbiano commissioned later in 1931. Bartolomeo Colleoniwas last to commission, in 1932, and was named after the Captain General of the Venetian army from 1455 to 1475. Her consort at Cape Spada, Giovanni delle Bande Nere, was named after the last great Condotierri, Lodovico de’ Medici.

A further two vessels were then ordered, principally along the same lines of speed over armour but with some speed traded for additional armour and some other minor design variations addressing weaknesses that had quickly been identified in the first four vessels. They were Armando Diaz, lost in February 1941, and Luigi Cardorna, the only survivor of the first six vessels. A major change was to move the catapult to amidships, enabling a re-design of the forward superstructure to reduce the top-heaviness of these two vessels. Together with the initial set of four they concluded the first built programme of six Condotierris, forming a distinct sub-group. At some time during this period, the Condotierriswere also re-classified as light cruisers.

While the high speed of the early Condotierri class ships impressed during trials, following their entry into service severe problems soon emerged. These were a range of seaworthiness challenges, partially caused by the design for high speed and light displacement. Problems included strong vibrations at high speeds and an overall lack of stability due to being top-heavy, both of which in turn affected gunnery performance. Immediate measures to address these included the replacement of the rear tripod mast with a simpler and lower structure, but nothing could be done about the fundamental design decisions, such as the narrow beam. To address the serious vibration issues, a project to strengthen the hulls of the first four Contotierris was carried out in 1938, together with the installation of more capable air defence. Given the multiple design issues, it has to be considered that the reduction in the initial construction programme from twelve to six was a fortuitous decision by the Regia Marina, since it enabled the design department to re-think and upgrade the later sub-classes, leading to vessels that were fundamentally more capable, if also significantly larger.

Given the almost 7,000 tons full load displacement of the di Giussano class, the most comparable Royal Navy class of cruisers was the Leander class, of similar displacement, armament and protection (see Table 2). A major difference to the Leander class, driven by very different needs of the two navies, was that ships of the di Giussano class were built for a high design speed of 36.5 knots rather than endurance, having a comparatively short steaming range of 3,800 nm at economical speed, and only 980 nm at top speed. Range however was no great concern to the Regia Marina, given the restricted nature of the Mediterranean waters in which it would fight, and the short distance to a number of bases available to it around the central Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea.

Armament, Armour and Equipment

The di Giussano class were armed with eight 152 mm/6” OTO M1926 guns as main battery, placed in four twin-turrets, two forward and two aft. This gun fired a 110 lb shell at a rate of 5 per minute to an impressive range of 31,080 yards, with a very high muzzle velocity of 3,198 ft-per-second. This design was in keeping with the Regia Marina philosophy of seeking to commence a naval gun battle at long range and aimed to enable the di Giussano class ships to outrange enemy destroyers. This capability seems to have influenced Admiral Casardi’s tactical approach during the Battle of Cape Spada. In reality however, this doctrine was undermined because the OTO M1926 gun suffered severe accuracy problems, due to the very close placement of the twin barrels, which led to shells interfering with each other in flight. The di Giussano classships also carried six dual-purpose 100/47 (4”) M1926 guns as secondary battery in three twin mountings amidships as a central battery. These guns, originally an Austro-Hungarian design and also used as the main gun on the Spica torpedo boats, acted as the main air defence battery and close-in defence. While they were good for range, they were too slow in operation to follow the faster, modern aircraft introduced by the Royal Air Force after spring 1942. Overall, between being top heavy and built with a narrow beam, the di Giussano class were a bad platform and suffered from poor sea-going ability. The rebuild in 1938/39 which aimed to increase stability could only partially address this. The compromised main battery performance had serious consequences during the Battle of Cape Spada.

In addition to their main gun armament, the di Giussano class carried four 533 mm torpedo launchers and were designed to more than 100 mines, albeit at the cost of blocking Y turret from operating while the mines were shipped. They also were designed to carry two float planes in a hangar under the forward superstructure, allowing them to be launched from a bow catapult. Due to the limited number of the IMAM Ro. 43 floatplanes being available, just one was carried when the war started. The location of the catapult was both unusual and impractical and in Luigi Cadorna and Armando Diaz it was moved to a more conventional central location.

On the defensive side, the armour of the di Giussano vessels barely achieved splinter protection and the ships were vulnerable to the standard 4” guns of Royal Navy destroyers. The idea was to be able to hit any attacking destroyer hard at a range from which they could not retaliate and to use speed to maintain this distance and pound them into submission. The crews nicknamed the di Giussanos ‘Cartoni Animati’, a play on the Italian term for the very popular Disney animated cartoons, but also meaning ‘Animated Cardboard Boxes’. Again, this design concept was to play a role in the initial phase of the Battle of Cape Spada, when the two Italian light cruisers faced only the four destroyers of the 2nd Flotilla but could not close on them due to this vulnerability. The ships were also very vulnerable to torpedo attacks, with all five vessels lost suffering catastrophic damage from torpedo attacks, particularly if hit in the forward section.

The close-in air defence battery as designed on the di Giussano class originally consisted of two First World War-era 40/39 single-barrelled AA guns and eight 13.2 mm twin machine guns. During the rebuilding programme in 1938/39, the modern 37/54 AA gun replaced the 40/39 variant and was considerably better, and twin-barrelled 20/65 AA guns replaced the 13.2 mm machine guns, also with improved results. During these refits the di Giussano class also received depth charge throwers for 40 depth charges, reflecting the changing ideas about their use. Other than these modifications, the di Giussano class did not receive improvements such as radar or additional AA guns during wartime, since most of them were lost before these technologies became available.

The di Giussano class originally carried a crew of 21 officers and 500 men. This increased by about 30% following their rebuild in the late 1930s, to enable the manning of additional weapons and to account for wartime requirements; Colleoni carried almost 650 men when she was sunk.

Table 2:

| Armour Section/Design Parameter | Di Giussano sub-class | Leander Class HMAS Sydney (II) | Difference % |

| Length (m), deck level | 169.3 | 171.4 | +1 |

| Width (m) | 15.5 | 17.3 | +12 |

| Draft (m) | 5.3 | 5.26 | -1 |

| Main armament | 8 x 152 mm | 8 x 6” (150 mm) | n/a |

| Main armament – range, yards | 31,080 | 25,480 | -18 |

| Secondary armament | 6 x 100 mm | 4 x 4” (100 mm) | -25 |

| Horizontal (mm) | 20 | 25 | +25 |

| Vertical (belt) (mm) | 24 | 51-76 | + 113 – +217 |

| Turrets (mm) | 23 | 25 | +8 |

| Control tower (mm) | 40 | n/a | |

| Engine power (hp) | 95,000 | 72,000 | -24 |

| Displacement full load (tons) | 6,954 | 7,198 | +3.5 |

| Design speed (knots) | 36.5 | 32.5 | -11 |

| Range (nautical miles) | 3,800 | 7,000 | +84 |

| Crew (peacetime, as designed) | 521 | 570 | +9 |

Service and Considerations up to the War

Despite rapidly approaching obsolescence within just a few years of being launched, the di Giussano class performed a number of roles in the confrontations with Great Britain in 1935 and 1936 during the Ethiopian crises and again in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. They also showed the flag around the world and Colleoni served on the China Station during the early years of the Sino-Japanese war in 1938-1939. Nevertheless, the question of what to do with these aging ships continued to occupy Supermarina, the Italian Admiralty.

To address the increasing air threat to naval vessels, the introduction of dedicated anti-air cruisers was considered by navies across the world and the Royal Navy converted its obsolete C-class cruisers in this way in the mid-1930s. In Italy, studies were undertaken to follow the same path with the four di Giussanos, to provide the fleet with AA cruisers for protection against air attack. At this time, a modern medium artillery weapon had become available to the Italian arsenal, in the form of the stabilised and electrically controlled 90/50 gun. This gun was destined for the new Littorio class battleships, the modernised dreadnoughts of the Duilio class and the second of two light cruisers of the final Abruzzigroup of Condotierri light cruisers, Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Two plans were made for converting the di Giussano class. The first proposed removing their main and secondary armament, replacing it with 16 single-mounted 90/50 guns, six each in place of A & B and X and Y turrets, with another four replacing the central artillery. The second plan proposed to use only 12 90/50 guns in single turrets, and add four of the modern 135/45 guns, considered the best gun design of the Regia Marina, in two twin turrets replacing the 152 mm A and B turrets. In addition, modern fire controls, rebuilding of the superstructure, and improvements to the armour scheme were considered, as well as replacing the light AA artillery

by 10 20/65 Breda guns in a concentrated central battery. Neither project progressed beyond the drawing stage, and instead of a costly conversion project, disposal was considered. Thus, while on the China Station, the Italian government offered Colleoni as a purchase to Japan, instead of bringing her back to the homeland. While negotiations progressed somewhat, they ultimately failed, and she returned to Italy via the Suez Canal in August 1939. Similarly, da Barbiano had been offered to Sweden during the winter of 1939/1940, but again the negotiations were not concluded, and only two early Spica class torpedo boats, Spica and Astore, were ultimately sold to the Swedish navy.

When war commenced, the early Condottieri class were considered obsolete due to insufficient protection and an unstable gun platform. Even their once impressive top speed was by now just a memory, despite Jane’s Fighting Ships perpetuating it for eternity. In the case of Armando Diaz, the top speed seems to have declined from 39 knots at her trials to 31-32 knots by 1941 and a still impressive maximum speed of 32 knots was reached by Bartolomeo Colleoniand Giovanni delle Bande Nere at Cape Spada, just sufficient to be faster than their opponents, allowing Bande Nere to escape.

Regardless of their weakness, in April 1940 the Ufficio Piani planning department of the Regia Marina stated, after long consideration, that the di Giussano class could again be considered suitable for service with the battlefleet, even if they would have to be considered as expendable ships. The four Condotierris of the first series were then divided between divisions, the 2nd Divisione with Bartolomeo Colleoni and Giovanni delle Bande Nere, and the 4th Divisione with Alberto di Giussano, Alberico da Barbiano, Armando Diaz and Luigi Cadorna. It was the 2nd Divisione that would meet Sydney and her accompanying destroyers in the Kythera Straits off Crete in the early morning hours of 19 July 1940.

The actual Battle of Spada will be covered in Part 2 of this series.