- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Australia I

- Publication

- June 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Laurie Watson

In the many memorial services to commemorate the centenary of World War I events, that commemorating the Battle of May Island is very likely to pass under the radar of much of the press and the organizers of ceremonies. May Island, or more correctly the Isle of May, is a speck of granite near the entrance to the Firth of Forth, far from Australia, yet the Royal Australian Navy lost one of its most promising young officers during the so-called battle, and the Royal Navy lost 105 of its officers and sailors on the night of 31 January 1918.

Despite being known as the Battle of May Island, the events of that night represented no battle at all, but rather a catastrophic series of blunders, miscommunications, ignorance, and sheer bad luck. So what was the ‘Battle of May Island’?

The C-in-C Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty, devised an exercise, known as Operation EC1, to exercise his cruiser squadrons and to practise fleet deployments. It was to be an enormous exercise involving twenty-six battleships from seven divisions of the fleet, plus nine cruisers and four destroyers, all from Scapa Flow. They would be joined by three units of the 5th Battleship Squadron, four units of the 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron, fourteen cruisers from various cruiser squadrons, numerous destroyers, and two flotillas of ‘K’ class submarines, all from Rosyth.

The exercise was scheduled to take place on the night of 1 February 1918, with the Scapa Flow and Rosyth forces meeting out in the North Sea.

Of importance to the events of 31 January is the nature and employment of the K-Class submarines. Fleet tactical doctrine still regarded submarines as normal fleet units that were expected to keep up with the capital ships, but diesel electric boats demonstrably could not do so. Consequently, the steam-driven K boats were developed. They were large for the time at 339 ft, and their steam turbines could drive them at 24 knots, but as a class they were plagued with a wide range of technical problems and soon earned the sobriquet ‘K-Kalamity Class’, or more ominously ‘K-Killers’.

Of the two submarine flotillas participating in EC1, the 12th flotilla comprised K-3, K-4, K-6, andK-7, led by the light cruiser HMS Fearless, while the13th flotilla comprised K-11, K-12, K-14, K-17and K-22led by the destroyer HMS Ithuriel.

The exercise began at 1830 on 31 January when the battle cruiser HMS Courageous led the force out of Rosyth with Ithuriel and the 13th Submarine Flotilla (SF) following in line ahead. At the same time, and five miles further up The Forth, the 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron consisting of HMAS Australia and HM Ships New Zealand, Indomitable, and Inflexible got under way. The battle cruisers were followed by Fearless leading the 12th SF, then the battleships, some of the destroyers, and finally the light cruiser squadrons. The entire fleet proceeded in line astern, and made rendezvous with screening destroyers further down The Forth.

The submarines were travelling at 16 kts two cables apart and although otherwise darkened, were showing blue, half-brilliance stern lights. At 1833 Ithuriel opened to 1200 yards astern of Courageous whose screening destroyers took station in the gap; the submarines of the 13th flotilla maintained station astern of Ithuriel. A few minutes later the ships ran into a low-lying mist and Ithuriel lost sight of Courageous. Simultaneously, twenty miles down the estuary eight armed trawlers sailed to sweep for mines, but incredibly nobody in the trawlers or at their reporting base on the Isle of May knew anything about EC1 or the movements of the Grand Fleet, nor did the Grand Fleet know about the sweeping operations.

In an attempt to regain visual contact with Courageous, Ithuriel and the submarines of the 13th Flotilla increased speed to 19 knots, but by now Courageous was abeam the Isle of May and increased speed to 21 knots as per the exercise order. The mist had reduced visibility for normal navigation lights to about one and a half miles. Events of the next few minutes raised the curtain on the forthcoming disaster when LCDR Harbottle, captain of K-14, 1200 yards astern of Ithuriel and watching intently the blue lights of the two submarines ahead, saw first K-11and then K-17apparently reduce speed and haul out to port. Harbottle maintained course but reduced speed to 13 knots when two hitherto invisible minesweeping trawlers ahead and on a collision course suddenly switched on navigation lights.

Harbottle in K-14ordered hard-a-starboard, whereupon his helm jammed, so he reduced speed to dead slow; his immediate concern was the submarine following, K-12, but he saw her pass safely astern; confident that K-22would be following in the track of K-12, Harbottle’s fresh concern was keeping clear of the battle cruisers, now about four miles astern. His helm suddenly freed itself, so Harbottle attempted to return to his station; K-22had lost sight of him, but suddenly the bridge staff of K-22saw a red navigation light close ahead, and at 19 knots and sluggish to turn, K-22ploughed into K-14.

K-22struck K-14 on the port side of the crew space, just abaft the bow torpedo compartment, severing part of the bow. Water rushed into the compartment, drowning two crew members immediately, but quick damage control action by the first lieutenant saved the boat from sinking. Both boats were in grave situations, with K-22 having two forward compartments flooded, and K-14 unable to move, down by the bows, and in imminent danger of sinking. Both switched on all navigation lights, radioed and flashed distress messages, and stood by with Very flares to warn the ships coming up.

Ithuriel and the three leading boats of the flotilla sailed off into the night, totally unaware of the drama behind them. It was over an hour before Ithuriel’s radio department picked up K-22’s distress call.

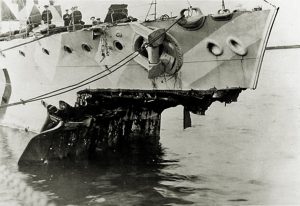

Fifteen minutes after the collision, at 1930, Australia, leading the four ships of the 2nd BCS with their accompanying destroyers was bearing down on the spot where the two submarines lay dead in the water, flashing and radioing their distress calls. Australia saw the flares and detached a destroyer to investigate and assist, while those on the decks of K-14and K-22 watched anxiously as the battle cruisers and destroyers swept past on both sides at 21 knots – all but the last battle cruiser Inflexible. She had lost sight of her next ahead, Indomitable, when lights were sighted ahead; there was confusion on the bridge as to what they were, and despite trying to take evasive action, Inflexible slammed into the stricken K-22at 18 knots, ripping her bows around so that they stuck out at 90º to the line of the submarine’s hull.

As Inflexible had started her evasive turn, her stern swung round crashing down the side of the submarine, tearing off her external starboard ballast and fuel tanks, and pushing the submarine down into the water so that only her bridge was above the surface. The propellers of the swinging battle cruiser then crashed down the side of K-22 before she drew clear. Amazingly, K-22 remained afloat, but equally amazingly Inflexible rushed off unheeding into the night.

K-14 lay close by, still afloat and firing off Very flares at a steady rate as surface ships raced by, alarmingly close. Ithuriel finally received K-22’s distress signal at 2010, about an hour after the collision. She signaled Courageous and Barham that she was turning around with the remaining boats of the 13th SF to assist two submarines in distress, but for unexplained reasons the coded message did not leave the ship for a considerable time. By now, the forty or more ships in the exercise were stretched over thirty miles of The Forth, heading seawards at high speed.

Having turned his ship and squadron back to assist the damaged K-22 and K-14, Commander Leir in Ithuriel was shocked to find Australia almost dead ahead and coming straight towards him. The battle cruisers were following a track further to the south than the submarines had followed, and Commander Leir had turned his flotilla directly into their path. He altered course rapidly, and avoided Australia by less than 600 yards, but the sluggish maneuverability of the three remaining submarines with him meant they had a much narrower escape. It’s estimated that K-12, last in the line, missed being run down by Australia by as little as three feet, and men on the upper deck of the battle cruiser reportedly could see the boiler fires down the submarine’s funnels.

Confusion ensued, and both Ithuriel and the three submarines found themselves dodging the battle cruisers’ escorting destroyers independently and as best they could. They wove their way safely through the destroyers and K-11and K-12found Ithuriel again, but K-17 had lost ground and fell about a mile behind. Still coming down the Forth and about five miles distant, Captain Little in Fearles swas leading the 12th submarine flotilla comprising K-4, K-3, K-6, and K-7in that order; near May Island he had intercepted K-22’s distress signal, informed the boats of the 12th SF, and instructed them to switch their blue stern lights to full brilliance and keep a look out for the damaged K-22and K-14.

By 2015 Captain Little in Fearless was past May Island and felt he was well clear of the scene of the collision, but the signal from Ithuriel warning the force that she and three submarines had turned around had still not left the ship. However at 2025 a signal had been sent from Australia warning the battleships behind the 12th SF that she had just passed Ithuriel and three submarines inward bound, but it came too late to warn Fearlessand her submarine flotilla. At about the same time as Australia’s signal went, Captain Little and his men saw the lights of three ships on their port bow and crossing their track; the first two crossed clear, but the third was some distance back – it was in fact K-17which had lost ground when dodging the destroyers. Captain Little had right of way and held his course, assuming the other ship would alter course and pass down his port side; it didn’t, and Fearless slammed into K-17at 21 knots just ahead of the conning tower. The crew of Fearless watched K-17 wrench free and bang down the side of the cruiser, with water pouring in through a great gash in her side. Within eight minutes K-17 had sunk, but the entire crew managed to escape into the frigid waters of the Forth Estuary, including an Australian Midshipman, Ernest ‘Dick’ Cunningham, on loan from HMS Glorious. The collision tore a great hole in the bows of the cruiser and flooded a number of her forward compartments.

Ithuriel, now with only K-11 in company, continued towards the spot where K-22 and K-14 lay wallowing, unaware of the mounting chaos going on around them. K-12, having slid down Australia’s side was now on collision course with K-6 of the 12th flotilla, but each saw the other just in time to take evasive action. K-6, which had been following K-3, had lost sight of her in the near-collision. He picked up a white light and, assuming it to be the stern light of K-3, took station on it; however within a short time, a starboard steaming light appeared, and K-6realised he had not seen K-3’s stern light at all, but the steaming light of another ship, which was on a collision course with him; the lights were in fact from K-4, and K-6ploughed into her at almost right angles travelling at 21 knots, almost cutting K-4 in two. The boats remained locked together, with K-4 sinking fast and beginning to take K-6down with her. Finally K-6’s frantically reversing propellers and her greater buoyancy let her break free, whereupon K-4 sank, taking her entire crew with her.

Within two hours of sailing, and before even reaching the open sea, the fleet had lost two submarines sunk, two more badly damaged, one damaged, one cruiser badly damaged, fifty-seven men dead, and fifty-five others thrashing around in near-freezing water. But the drama was not yet over.

Submarine K-7, following astern of K-6 in poor visibility suddenly saw the sinking K-4 dead ahead, and in an attempt to avoid hitting her, put her engines full astern; in the event, K-7 still hit K-4 but in going hard astern her propellers sucked in and killed the majority of the crew of K-17. Only eight members of the crew survived. One who did not was Midshipman Cunningham, a graduate of the 1913 RANC entry; he had been a cadet captain, good sportsman, and had gained maximum time and several academic prizes on passing out from the RANC. He had also won the Grand Fleet Bantamweight Boxing Championship in 1917.

After her collision with K-17, Fearlesssent a priority message to Barham reporting that she had sunk the submarine, and the signal from Ithuriel advising she had turned around finally left the ship – twenty minutes after she had done so. It was now 2038. Once again, it was too late for the battleships to alter course and they and their escorting destroyers swept through the place where the remnants of the submarine flotillas were wallowing in the fog. In only three terrifying minutes they tore through the spot at 21 knots, miraculously but narrowly avoiding further collisions with the stricken submarines and those standing by to assist, but washing several men off their decks with their bow waves.

Fearless and K-22 with their gaping bow wounds crept back to Rosyth stern first; K-14 was towed back, and Exercise EC1 went ahead as planned. Little wreckage and very few bodies were ever found. A board of enquiry was convened after the exercise and blame was apportioned amongst five officers from the ‘K’ boats, but only one was court martialled for hazarding his ship, and reprimanded. Being wartime, all records relating to the ‘Battle’ of May Island were then sealed, but after the war it suited the Admiralty to keep them sealed, and in effect suppressed, and they were only reluctantly released in 1994 after surveyors for a wind farm came across the wrecks of K-4and K-17. A memorial to those lost in the submarines was unveiled in 2002 at Anstruther on the mainland near the Isle of May.

Acknowledgments:

World Naval Ships Forums – Notes ‘Battle of May Island’.

‘Battle of May Island’. UK Ministry of Defence 30 Jan 2002.

Thanks to VADM Peter Jones AO DSC RAN Rtd for clarifying several conflicting points.