- Author

- Australian-American Association

- Subjects

- WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- August 1972 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Into the Coral Sea

At about 0800 on May 3 the Tulagi Invasion Group made an unopposed landing on the beaches which United States Marines were to win back three months later. The Port Moresby Invasion Group was still anchored at Rabaul, scheduled to leave at 1800 next day.

On May 4, planes from Yorktown made three separate attacks on shipping in Tulagi harbour, damaging one destroyer and sinking a few smaller ships.

By May 5 the Port Moresby Invasion and Support Groups were steaming merrily along a southerly course aiming at the Jomard Passage through the Louisiade Archipelago. The Japanese Striking Force was beating down along the outer coast of the Solomons. By dawn on May 6 the enemy carriers were well into the Coral Sea. By the afternoon of the 6th, Intelligence confirmed that the Port Moresby Invasion Group would turn the corner of New Guinea through Jomard Passage, and that they would come through next day for the 8th, if not stopped. At 1930 on May 6, Admiral Fletcher resumed course to the north-westward to be within striking distance of the Port Moresby Invasion Group by daylight on May 7.

The main action of the Battle of the Coral Sea should have been fought on May 6, and would have been if either Admiral had been aware of the others presence.

By midnight on May 6 the Port Moresby bound transports were closing Misima Island, almost ready to slip through Jomard Passage. The Covering Group was protecting the left flank of the Port Moresby invaders, Shoho furnishing the combat air patrol until sundown.

This was the day, May 6, that marked the low point of the war for American arms; General Wainwright was forced to surrender his forces in the Philippines. But on the very next day there opened a new and brighter chapter in the Pacific war. The time had come for the Allies to take their first step forward. The transition from Corregidor to Coral Sea is startling, dramatic and of vast importance.

Actions of May 7 – Loss of US Ships Neosho and Sims

The Japanese Striking Force reversed course to the northward on the evening of May 6 and maintained it until two hours after midnight, when it turned again and headed south.

Sims was patrolling about a mile ahead of Neosho shortly after 0900, when fifteen high-level bombers attacked, missed and disappeared. At 1038 another group of ten made a horizontal bombing attack on Sims, which avoided nine bombs dropped simultaneously. After noon her number came up when 36 dive-bombers arrived. The planes came in from astern in three waves. Three 500-pound bombs hit the destroyer, two exploded in her engine-room, and within a few minutes she buckled amidships and sank stern first.

In the meantime, 20 dive-bombers concentrated on Neosho. Within a few minutes they scored seven direct hits and eight near-misses, one by a ‘suicider’ who exploded against No. 4 gun station; gasoline burst from the plane’s tanks and flowed blazing along the deck. Captain Phillips ordered all hands to ‘make preparation to abandon ship and stand by’. She drifted for four days and was finally scuttled on May 11.

Sims and Neosho did not die in vain. If they had not drawn off this strike, Japanese planes might have found and attacked Fletcher on the 7th, when the American planes were working over Shoho.

Crace’s Chase

Admiral Fletcher, at 0625 on May 7 ordered Admiral Crace’s Support Group to attack the Port Moresby Invaders, which reconnaissance planes reported heading for Jomard Passage.

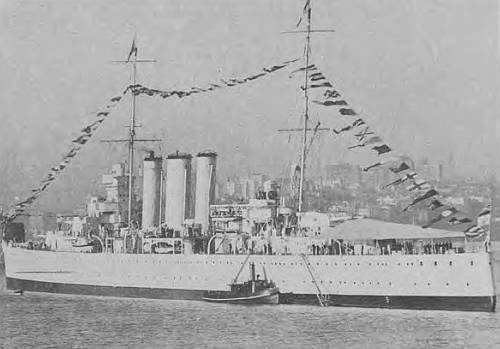

At 1358 Crace’s group, consisting of Australia, Chicago and Hobart, was attacked by eleven single-engine land-based planes. All ships opened fire and drove them off. Immediately after, radar picked up twelve Sallys (land-based Navy bombers) 75 miles away. Crace ordered radical manoeuvres and every ship opened fire as the planes came in low. Eight aerial torpedoes were dropped, but all missed and five of the bombers were shot down. Immediately after the surviving torpedo planes had retired, 19 high-flying Sallys dropped their steel eggs from an altitude of 15,000 to 20,000 feet. The ships dodged the bombs as they had the torpedoes and the planes flew away.

By midnight Admiral Crace had reached a position about 120 miles south of the New Guinea bird’s tail. He continued on course part of the night and then, having heard that the Port Moresby invaders had turned back, headed south.

As the Japanese attack was of the same type and strength as the one that sank HM Ships Prince of Wales and Repulse on December 8 1941, the escape of Crace’s Support Group without a single hit is a tribute to its training, and to the high tactical competence of its commander. The Japanese thought they had bettered the score of December 8. They claimed having sunk Chicago and Australia, and having torpedoed another battleship.

Sinking of Shoho

While the planes of the Japanese Striking Force were slaughtering Neosho and Sims, the Port Moresby Invaders still were moving toward Jomard Passage. However, Japanese planes had now discovered the United States carriers. The Port Moresby Invasion Group was consequently ordered to turn away instead of entering Jomard Passage. Thus 0900 on May 7 marked the nearest that this or any other Japanese naval force got to Port Moresby.

Shoho, having been located, was immediately attacked. Ten SBDs attacked at 1110, Lexington’s torpedo squadron followed seven minutes later, and Yorktown’s air group piled in at 1125. Ninety-three planes against one light carrier! No ship could have survived such a concentration. After receiving two 1,000-pound bomb hits, she burst into flames and went dead in the water. More hits followed, and by 1130 the entire vessel was damaged by bombs, torpedoes and self-exploded enemy planes, records the Shoho war diary. Abandon ship was ordered at 1131, and the carrier sank within five minutes.