- Author

- Australian-American Association

- Subjects

- WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- August 1972 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Carrier Battle of May 8

Yorktown and Lexington v. Shokaku and Zuikaku

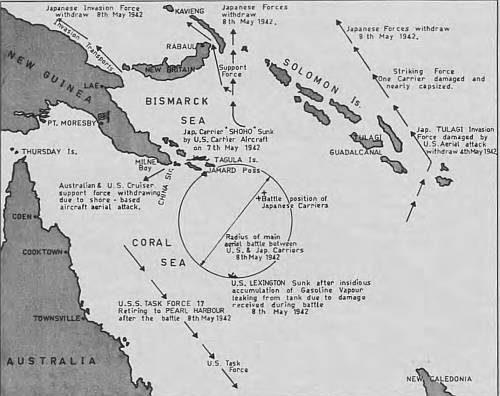

The decisive action was fought out in a carrier battle on the morning of May 8. The number of planes operational on both sides was almost the same: 121 Japanese and 122 American.

At 0838 Admiral Fletcher ordered both US carriers to launch air strikes. The Yorktown group of 39 planes took off and at 0915, an hour and a quarter later, the attack on Shokaku commenced. Only two bomb hits were scored, one well forward, which damaged the flight deck, and the other well aft, which destroyed the repair compartment. Lexington dive-bombers added one more hit.

Shokaku lost 108 men killed and 40 wounded, but was not holed below the waterline, and at 1300 she hightailed it for home. She almost capsized on the way, and arrived in bad shape; but she got there. Admiral Takagi had no qualms about releasing Shokaku, for by this time he believed that both United States carriers were well settled on the bottom of the Coral Sea.

By the time the American planes began returning to their carriers, both Yorktown and Lexington had been hit. Ninety planes from Shokaku and Zuikaku were beating up the American carriers a few minutes after Yorktown’s attack on the Japanese carriers ended and before Lexington’s had commenced. In this strange crisscross air battle, superior success attended the Japanese, whose strike group was larger and better balanced and more accurately directed to its target than that of the Americans.

At 1118 the Japanese approached from the north-eastward, down-wind and down-sun. Torpedo-bombers came in on both bows of Lexington to launch their fish from an altitude of 50 to 200 feet. One hit on her port side forward was quickly followed by a second on the same side opposite the bridge. One small bomb exploded in an ammunition box on the port side of her main deck, another scored on the smokestack structure. Near-misses ruptured plates and raised huge plumes of water. It was all over in nineteen minutes.

Six minutes later Yorktown was attacked. For the next three minutes she dodged steel eggs, then received her one and only hit. An 800-pound bomb struck the flight deck and penetrated to the fourth deck. Sixty-six men were killed or seriously injured, mostly by burns. Owing to skilful handling, Yorktown escaped with damage that did not impair flight operations.

The big carrier battle was over by 1140 on May 8. But at 1247 a devastating internal explosion shook Lexington from stem to stern. More eruptions followed, each more violent than the last. At 1707 abandonment was ordered and destroyer Phelps administered the coup de grace with torpedoes. At about 2000 the battered amazon, with one final detonation, slipped into a 2400-fathom deep.

Invasion Thwarted

But the enemy had retired; his main objective, the invasion of Port Moresby, had been thwarted. Before the end of May 8, Inouye formally postponed the Port Moresby invasion until July 3! (But Midway settled that.) One may well ask what prevented the Invasion Group from reversing course again and steaming through Jomard Passage to its original destination instead of returning to Rabaul. The Army Air Force may take a bow for that. Inouye did not dare to risk his transports in a second try, because of the intense activity of the Allied Air Force along the southern shores of Papua, and the want of air protection now that Shoho was sunk and the Striking Force had retired.

The Battle of the Coral Sea will be ever memorable as the first purely carrier-against-carrier naval battle in which all losses were inflicted by air action and no ship on either side sighted a surface enemy. It was a tactical victory for the United States. The enemy inflicted relatively greater losses than he sustained; Shoho and the few small ships sunk at Tulagi were a cheap price to pay for Neosho, Sims and Lexington.

On the other hand, the main purpose of the Japanese operation, the capture of Port Moresby, was thwarted. The Louisiades proved to be a barrier beyond which no warship flying the banner of the Rising Sun could ever pass. Tulagi, one of the two secondary objectives of the enemy, had been won and it cost us dear to root him out of it. But in the other scale one must place the temporary elimination of Shokaku and Zuikaku. The former was so damaged that she could not rejoin the fleet for two months, and the latter, owing to plane losses, was out of the war until about June 12. If these two fine carriers with veteran pilots had been able to participate in the Battle of Midway, they might well have supplied the necessary margin for victory.

Call Coral Sea what you will, it was an indispensable preliminary to the great victory of Midway. The morale value of the battle to all Allied nations, coming as it did immediately after the surrender of Corregidor, was immeasurable. It was a story of cool efficiency, relentless action, determination and superb heroism.

Less than a month later, on June 4, Japan lost four of her best carriers at the Battle of Midway – which was the turning point of the Pacific War. Coral Sea was the end of the beginning – Midway was the beginning of the end.

Acknowledgement: Australian-American Association.