- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2, Naval Engagements, Operations and Capabilities

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

The December 2022 edition of this magazine contained an article A Lonely and Dangerous Vigil regarding New Zealand Coastwatching operations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. Comments were made that the naval guns on the Gilbert Island of Tarawa had been captured following the fall of Singapore. It now appears that this was in error.

Further investigation at the Imperial War Museum has produced evidence that there were no 8-inch guns guarding the approaches of Singapore to be captured. The company records of Vickers, the armament manufacturers, show that the guns were part of a consignment of 12 x 8-inch guns sold to the Japanese in 1905, during the Russo-Japanese War. The guns at Tarawa therefore came from a legitimate transaction between British and Japanese authorities and had nothing to do with the conquest of Singapore in February 1942.

The Gilbertese Islands

The Gilbert & Ellice Islands were a British colonial outpost until they became independent, with the larger Gilbert group becoming part of Kiribati in 1979 and the Ellice group becoming Tuvalu in 1978.

The Gilbert Islands are a chain of 16 atolls and coral islands which straddle the equator. One of the largest of these is the Tarawa atoll with its sizeable lagoon about 30 km in length and 20 km wide. Makin, another atoll, lies about 200 km north of Tarawa. Their location was considered of strategic value and occupied by the Japanese just two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

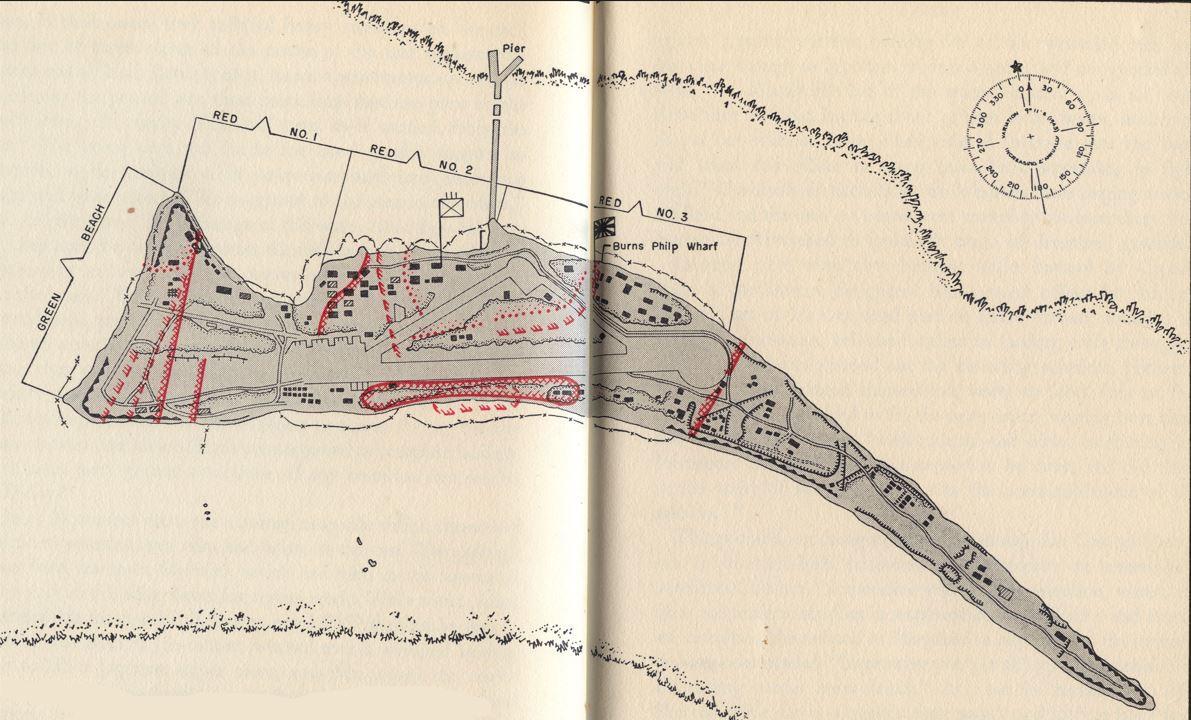

The main Japanese base was on Tarawa’s Betio Island which at about three metres above sea level lies within the atoll and is only 3.2 km long and 730 m across at its widest. About half of the length of the island was devoted to an air strip used by bomber and fighter aircraft. The island is completely surrounded by a reef which is about 500 m from the shoreline. A long pier extended into deep water beyond the reef. A smaller garrison was inserted on Makin Island which was used as a seaplane base.

Major Japanese forces occupied Tarawa on 15 September 1942. The initial garrison of 2600 men came from the 6th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force (Marines), who were later joined by 1250 men of the 111th Pioneers assisted by a Korean labour force of 970 men. The combined force was known as the 3rd Special Base Defence Force.

Defence of Tarawa

The first commander of the Japanese force was Rear Admiral Tomonari Saichiro, an engineer who designed a sophisticated defence structure. This included integrating the older heavy calibre naval guns with smaller artillery pieces. These were linked to a large number of pillboxes and firing pits which provided interlocking fields of fire over the landing beaches. The beaches were further protected by minefields and aprons of barbed wire. Bomb-proof shelters were also provided to protect against naval bombardment and air attacks. Rear Admiral Keiji Shibazaki, an experienced combat officer from campaigns in China, replaced Admiral Saichiro on 20 July 1943.

In defence of the island were four obsolete 8-inch naval guns, 10 x 5.5-inch guns, plus 40 other smaller calibre artillery guns, anti-aircraft guns, heavy machine guns and 14 small tanks. There were no naval ships based here and only a limited number of aircraft. The defenders numbered about 2700 effective troops and 2100 auxiliaries who were mostly unarmed.

The Makin atoll was estimated to be defended by 284 Marines from the 6th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force, 108 aviation personnel attached to the seaplane base, 138 men from the 111th Pioneers, and 276 Korean labourers, a total of about 800 men of whom only 300 were armed and trained troops. They had four AA guns, four artillery guns, three light tanks and 20 machine guns.

Eight-inch Shielded Naval Guns

Four of these guns were installed on Betio Island, two on the southwest corner and two on the southeast coast. The two guns on the southwest corner were mounted in a tandem arrangement in concrete emplacements, which were banked all around with sand and coral. The two guns on the southeast coast were located in circular concrete emplacements about three metres above the ground. The two emplacements were about 30 m apart. Ammunition was stored in four heavily constructed bomb-proof magazines, at the rear of the guns. A narrow-gauge railroad track led from the magazines to an ammunition ready-use-room which separated the two gun positions. Small hand-drawn cars were used on the track.

The fire-control system for this installation included a plotting room in a lower level of the upper gun emplacement, an observation tower (20 m high), and the necessary wire and voice-tube comm-unication between these elements and the guns. These faithful guns fired the first rounds of the battle and kept all the American ships at a safe distance until they were found by the battleships’ big 14-inch guns and put out of commission. These eight-inch guns had the important effect of keeping the invading ships well offshore, involving a lengthy passage by landing craft, many of which were sunk by gunfire in deep water and others sank when crossing the reef with resultant heavy casualties.

Planning for Invasion of the Gilberts

Within the Pacific theatre there were two broad commands, with General MacArthur responsible for South-West Pacific and Admiral Nimitz responsible for the Pacific Ocean Area, with the Gilberts falling under control of the latter, with its command structure initially based in New Zealand. For this reason, the Gilberts tend to be overlooked in Australian historical records.

Following the success of the Guadalcanal campaign the 2nd Marine Division was withdrawn to New Zealand for R&R and new recruits replaced losses. Under General Julian C. Smith, the 2nd Marine Division, now of 16,000 men, sailed from New Zealand to join Operation GALVANIC for the liberation of the Gilbert Islands. The major component of the invading force came from Hawaii. Under Admiral Spruance the 5th Fleet gathered, comprising five aircraft carriers, three battleships, four cruisers, 22 destroyers, two minesweepers and 18 transports. They embarked the 17,000 men of the 27th Infantry Division under the command of Major General Ralph C. Smith on 10 November 1943.

In their planning American forces were assisted by Lieutenant Commander G.H. Heyen RANR1 who had many years of operational experience in the Gilbert Islands. He participated in planning a total of 19 amphibious landings; in many of these he was on the lead landing craft as First Wave Navigation Officer, including Makin Island.

American intelligence suggested the defending force consisted entirely of naval personnel. Naval units of this type were usually more highly trained and have greater tenacity and fighting spirit than the average Japanese Army unit. The estimated strength of the Tarawa garrison was 2700 to 3100 men. At Makin the garrison was only estimated at 300 to 500 troops supported by 300 unarmed Korean labourers. The size of the invading force might be seen as a ‘sledgehammer to crack a nut’ approach.

The Battles of Makin and Tarawa

While this article mainly concentrates on Tarawa it cannot be divorced from Makin as the operations were conducted simultaneously. Almost unopposed bombardments from the battleships’ 14-inch, cruisers’ 8-inch and destroyers’ 5-inch guns together with air strikes from the supporting carriers continued for up to a week before the landing phase.

The Japanese defenders knew there would be little or no naval support and the few aircraft available had relocated due to the relentless bombing raids. Despite this, two aircraft found and reported the location of the US 5th Fleet but one of these was shot down. The objective of the defenders was therefore to delay the invasion as long as possible and to cause maximum damage and casualties to the invading force. There was nowhere to retreat.

The invading force did not have everything going their way as during the initial bombardment No 2 turret in the battleship USS Mississippi exploded, killing 43 men. At 5.10 am on 24 November, just towards the end of the battles, the escort carrier USS Liscome Bay, which had been providing air support, was sunk off Makin Atoll when hit by a torpedo fired by the Japanese submarine I-175. She sank within 20 minutes resulting in the loss of 646 lives and 23 aircraft.

After a week-long bombardment by ships and aircraft, on 20 November 1943 Marines from the 2nd Marine Division began one of the first full-scale amphibious assaults against a fortified target and learnt valuable lessons for the rest of the American island-hopping campaign. In a brutal 76-hour struggle, and one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific, there were some 3400 marine and naval causalities, of which more than 1000 died. In this hard-fought battle 4800 defenders (only half were combat troops) fought nearly to the last man, and only a handful of Japanese and Koreans escaped with their lives.

Also on 20 November some 7000 troops from the 27th Infantry Division embarked in the first wave of landing craft bound for the beaches of Makin Island. Here the resistance of the smaller defence force was limited. Over two days of fighting the Americans lost 66 killed and 150 wounded. Japanese losses were over 600 killed and 120 prisoners (mostly Koreans).

The high number of casualties was blamed on the ineffectiveness of naval and air bombardments against heavily fortified positions. But most importantly the landing proved much more difficult than anticipated in crossing a reef fringed atoll where the invaders, in poorly protected landing craft, were first exposed to intense heavy fire from large calibre guns and as they came closer, from heavy machineguns.

A number of war correspondents had been embarked to witness this operation, some of whom wrote accurate reports, but others sensationalised the horrors of Tarawa, creating the impression the attack had been a sort of ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ – gallant but futile, and someone had blundered.

General MacArthur later wrote that: ‘these frontal attacks by the Navy, as at Tarawa, are a tragic and unnecessary massacre of American lives’. Future armed landings in the Pacific were modified from the bitter experiences learned at Tarawa.

In time, Tarawa became a symbol of raw courage and sacrifice on the part of attackers and defenders alike. Ten years after the battle, General Julian Smith paid homage to both sides in an essay in Naval Institute Proceedings, where he saluted the heroism of the Japanese who chose to die almost to the last man.

Notes:

1 Gerhard Heinrich Heyen (1900-1959) was a Danish seafarer of German origin who on marrying a local lass (Hilda Harder) settled in Adelaide. His first command was the three-masted barquentine Alexa which traded in the Gilbert Islands. He later commanded steamships of the British Phosphate Commission. Joining the RANR(S) in 1935 he was called to active service in 1939. During operations in HMAS Kanimbla he was Mentioned in Despatches and in August 1940 was promoted LCDR RANR(S).

In August 1943 he was transferred to serve with the United States Navy, then planning Operation GALVANIC. At the landing on Mariana Islands on 15 June 1944, under difficult circumstances, he commanded a US Ship (the minesweeper YMS 323), probably the only Australian to do so in wartime. In June 1945, he received personal praise from Admiral R.K. Turner USN ‘with sincere thanks for two years of loyal and efficient assistance’ and was awarded the United States Legion of Merit. He was placed on the Retired List on 30 May 1945, receiving the Reserve Decoration, and returned to life in the Merchant Service.

References

Alexander, Joseph H., Across the Reef: The Marine Assault of Tarawa, United States Marine Corps, Washington DC, 1993.

McQuarrie, Peter, Tarawa Through Japanese Eyes, Warfare History Network, McLean VA, Feb 2023.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II – Vol VII, Little, Brown & Co, Boston, 1951.

Wright, Derrick, Tarawa 1943: The Turning of the Tide, Osprey, Oxford, 2004.

En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tarawa.

The Capture of Makin 20-24 November 1943, Centre of Military History United States Army, Washington DC, 1990.