In 1939 Sydney had a shortage of onions. A period of drought had affected the Victorian crop, and in order to fulfil the demand for the 20, 000 tonnes of onions consumed by the city every year, imports became necessary. Most of the imported onions came by boat from Japan or Egypt.

One of the shipments of onions from Egypt arrived in July 1939. They had been on a longer than expected journey as the ship they were originally transported on, the Aagtekerk, had run aground off the Indian coast. Another ship, the Algenib, took the cargo, including the 8000 bags of onions, and continued on to Australia.

By the time the Algenib arrived in Fremantle, something was wrong with the onions. Many had become “rotten and pulpy” and “gave off an offensive stench”. In Fremantle the dock workers refused to dispose of the more rotten of the onions unless they received higher pay, a request that was grudgingly granted. With the most rotten of the onions disposed of, the shipment continued to Sydney.

Algenib

By the time the ship reached Sydney the remaining onions were rotting. The Newcastle Sun reported the arrival of the Algenib into Sydney and passengers hurrying away from the ship, which smelt like a “fermenting pickle factory”. What was to be done with the 400 tonnes of condemned onions?

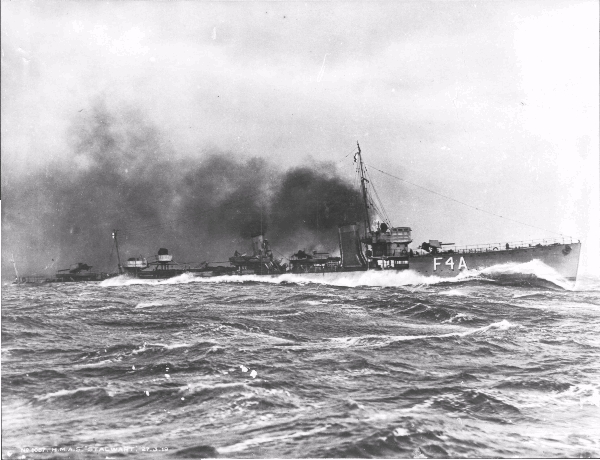

Penguin Ltd. salvage company came to the rescue. In 1939 they had bought five obsolete warships which they were in the process of stripping and preparing to scuttle outside the Sydney Heads. One of these ships, the Stalwart, was ready to be towed out to sea and wrecked, and so it was decided that the ship and the onions would be sunk together.

HMAS Stalwart I

The bags of onions were stacked onto the Stalwart, piled up in the mess hall, stuffed into the cabins and packed around the funnel. Before dawn on July 22st the Stalwart was towed out from Darling Harbour by two of Penguin Ltd’s tugboats, towards the ship graveyard off the coast of Sydney. 20 miles out from Sydney Heads the seacocks were opened and a the ship detonated, sinking with its odorous cargo to the sea floor below.

This, everyone thought, was the last of the onions.

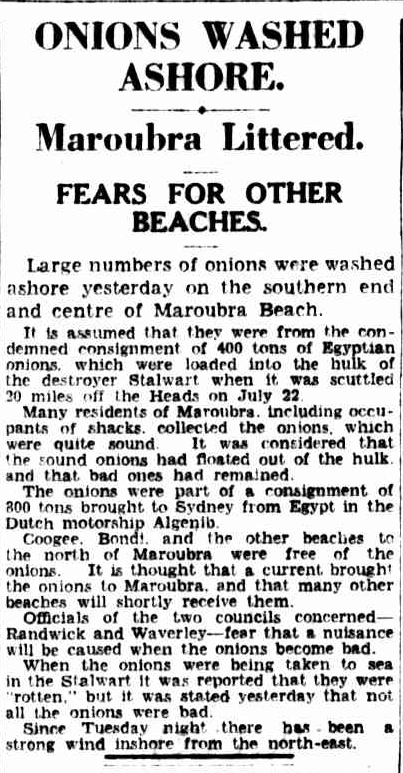

Two weeks later, on the morning of August 3rd, Maroubra locals were greeted with an unusual sight. Onions were washing up on the beach, thousands of them, and piling up on the shore. The Commonwealth Health Department were in dismay, as a year earlier they’d performed a test to chart how far debris needed to be dumped to prevent it returning to shore. The onions were more persistant than the red sticks the Health Department had used in their test and had, with the assistance of strong north-east winds, returned.

“Onions washed ashore” reported the Sydney Morning Herald, “fears for other beaches”. Coogee and Bondi residents readied themselves for the onion tide. Back in Maroubra people were salvaging the best of the onions for sale: there was still an onion shortage at the time, after all. The Department of Health declared that, if the onions were in good condition, they could be legally traded.

The Sydney Morning Herald Friday 4 Aug 1939