- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Janet Roberts Billett

This article follows from Part 1 by the same author on the contribution made by members of the Dominion Yachtsmen Scheme, which appeared in the December 2019 edition of this magazine.

By the beginning of 1944, the Allies had completed much of the planning for the major invasions of the French coast and plans for the relevant operations had begun. As part of ‘Operation OVERLORD’, the ‘Operation NEPTUNE – Naval Orders (ON1)’ stated that the object was:to carry out an operation from the United Kingdom to secure a lodgement on the Continent from which future operations can be developed. This lodgement must contain sufficient port facilities to maintain a force of 26 to 30 divisions and enable this force to be augmented…at the rate of three to four divisions in a month.1

It was to be a combined British and United States undertaking by all the services of both nations. Apart from the early operations to deceive the enemy about the position and forces for the landing, the mammoth task was the assembling and loading of a 4,000 vessel-strong D-Day armada with immediate support of follow-up forces and supplies, the Mulberry harbours, the naval-covering forces of the invasion and the varied ships, craft and equipment needed for maintenance services following the invasion.

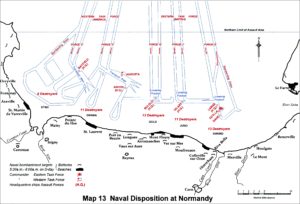

The Western Task Force (US) assault wave, of predominately US forces was on two beaches, UTAH and OMAHA while the Eastern Task Force (British and Canadian) assault wave was to the beaches code-named GOLD, JUNO and SWORD. Barnett stated that on D-Day, the assault forces of Eastern Task Force completed their much shorter runs to the beaches without losing formation, despite a short, sharp sea and that this was a tribute to the conning of the unhandy landing craft. It was in these smaller vessels that the majority of the Yachtsmen Scheme officers served. The men believed that at least 200-300 of their number were involved in D-Day landings at Normandy. The landing craft groups were supported by the big fleet destroyers with guns firing at enemy batteries behind the beaches. Ahead of them were the smaller Hunt class destroyers. The sky was full of bombers and fighters and the noise and smoke of the combined Allied bombardments was horrific. Veterans of amphibious landings comment on the cacophony of sound which dominates an amphibious assault. It is impossible to imagine the action and noise of a naval bombardment. The scale of the D-Day amphibious assaults for those who were involved was a unique combat experience.

It is not the purpose of this narrative to cover the details of the planning of the landings or the operational realities of such a huge undertaking which have already been thoroughly described in official histories and by other distinguished military historians. Rather it is hoped that it will give some insight into the roles and experiences of the many RANVR Yachtsmen Scheme officers who were involved.

In the Battle Summary Vol II for ‘Operation Neptune’: Landings in Normandy June 1944. Appendices, twelve RANVR are identified as in command. Of these, eight of the men are Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers. Temporary (Ty) Lieutenant John Larson2 from West Australia in MMS 7, a minesweeper of 115th MS Flotilla, is in Bomb Force D. In the Coastal Force Flotillas were Ty Sub-Lieutenant John Ferguson commanding MTB (Motor Torpedo Boat) 209 of the 13th MTB Flotilla and Ty Lieutenant William Fesq DSC of the 63rd MTB Flotilla.

Five Officers were in command of Motor Launches, Ty Lieutenant George Ramsay DSC from Sydney in ML 185 in 1st ML Flotilla, Ty Lieutenant John Honey, who enlisted in Fremantle, in ML 114 of 2nd ML Flotilla, Ty Lieutenant Lex Dunn, a Brisbane enlistment, in ML 442 of 21st ML Flotilla and Ty Lieutenant Robert Goodman, another Fremantle enlistment, in ML 588 of the same Flotilla. Lieutenant Commander George Dixon DSC from Sydney was in command of LST 409 of 2nd LST Flotilla. Dixon was a veteran of the Dardanelles campaign in World War I. His DSC was awarded for Operation HUSKY, the assault on Sicily preceding the Normandy landings.

Ferguson and Ramsay were both awarded a DSC for their work during the landings – Ferguson whose task was to safeguard the passage of troops and supplies across the Channel from the attacks of German E-boats, and Ramsay who conducted mine sweeps in adverse weather conditions and the transportation of wounded and German POWs back to Portsmouth.

Lieutenant Alfred Weston from South Australia commanded and trained the 59th LCT Flotilla of twelve ships for the assault on OMAHA beach where the German defences were the strongest. He was awarded an MID.

Lieutenant William Fergusson from Hobart was in HMS Misoa, a veteran of the D-Day Landings, when several months later a Sherman tank being transported to France caught fire, a very dangerous situation. Fergusson took charge of the firefighting team and managed to successfully extinguish the blaze. He was awarded an MID.

Sadly, one of the Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers, Sub-Lieutenant Richard Pirrie from Melbourne, was killed in action on D-Day. He was the commanding officer of a landing craft to land a spotting officer for a battery of self-propelled artillery, which he achieved, but his craft was hit by enemy fire while simultaneously detonating a mine. He was awarded a posthumous MID. Incredibly he was the only Yachtsmen Scheme casualty for D-Day. Lieutenant Ken Dyson remembered him as one of the few officers who carried a cane – very proper!

HMS Ajax was the first of her group of cruisers to destroy her target on D-Day morning. She had three RANVR Lieutenants on board – one Officer-of-Quarters in a 6-inch gun turret, one as action Officer of the Watch and one in charge of high angle armament. They were Alf Pearson and John Evans Read, both from Sydney, and Bob Fotheringham from Brisbane.

Writing about his war experiences many years later, John Read recalled:

Our first target was a nest of heavy coastal defence guns. After an exchange of fire lasting…17 minutes we asked for another target. We started at GOLD Beach next to the American sector and…then moved through JUNE and SWORD, plus a hasty trip to Plymouth for 6‑inch ammunition. Our last task was a bombardment near Caen, very nearly at our extreme range at 24,000 yards. After a few shots the Army asked us to go home as our shells were falling way short, into our own troops.

Our guns were so badly worn, you could actually hear the shells rattling as they went up the barrel so it was off to Portsmouth to have new guns fitted to our turrets.

We did not return to Normandy as the action had moved too far inland…so it was back to the Mediterranean to join the south of France invasion force.

Many of the Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers, although not recognised with awards, distinguished themselves with courage and ‘devotion to duty’ in their particular service. Conditions of living in the little ships were not easy and while this was recognised with an extra payment called ‘hard-lying money’ (still paid in the RAN today), it was not received until after the war’s end. Unlike the larger vessels both officers and men shared the very basic, even primitive, accommodation and victualling arrangements. Lieutenant Ken Dyson, who turned twenty-two on D-Day, served as 2IC of LCT 708 Flotilla, of twelve little boats. The flotilla was responsible for assisting in the landing of amphibious tanks, each little LCT carried three tanks. He described them as having:

a square canvas surround with ribs around it and rubber tubes in each corner…which (when they wanted to enter the water), was inflated with compressed air, they used to pull the sides up and that made a little boat. The tanks were very heavy and they couldn’t see where they were going very well, so that is where we came in. We had to lead them onto the beach (GOLD beach in his case)…it was pretty dangerous. They could only go about three to four knots and we had to keep a straight course. If we had been shot at, we would have been sitting ducks.’3

When the flotilla was in position the sea was too rough to land so they waited about a mile off shore. That night they started laying smoke which continued every night for three weeks, mainly to protect the landings as well as the Headquarters ship HMS Bulolo. In the flotilla there were 48 crew in total so they had to live on old merchant ships which had been sunk as a breakwater.4 This was necessary as the LCTs were only about 37 feet long, no room to sleep, no toilet or bathing (a bucket over the side) or cooking facilities. They would go out to the cruiser to get a box of food. Living was really hard.

Sub-Lieutenant Bernie Nelson, who commanded LCT 1038, was involved in landing soldiers and tanks on GOLD beach in the initial landings. While looking for survivors and recovering a couple of bodies, the landing craft was damaged when it struck a mined obstruction which blew out the bottom plates in the engine room. While they still had power in the engines they got away at full speed from the beach. LCT 1038 was towed back to UK on 9 June, for repairs which was quite a saga and is noted in HMAS Mk III.5 Years later Bernie Nelson wrote of these experiences:

We were taken to the nearest anchorage…a mile or so out to sea. We slipped our anchor off the quarter deck which was awash and secured the line on one of the bollards which was still intact.…at dusk, all the other ships weighed anchors and headed off as a result of a general signal to proceed to main anchorage as an E-boat attack was imminent. We called up a passing Canadian LCI for a tow…we had no power whatsoever. No sooner had we got underway an air raid started, this was the only sign of enemy aircraft all day. The LCI clapped on speed despite our request to reduce speed before the tow rope parted, a request they ignored…they disappeared into the darkness and we were left stranded…with no other ship in sight. The Coxswain then arrived on the bridge with his usual wry look on his face and said, ‘the anchor, Sir’. ‘What anchor?’ I replied. ‘The one in the forward locker’ he replied.’ (This anchor had been acquired by some of the crew from a memorial garden outside the Dockyard Commander’s office in Portsmouth, just before LCT 1038 sailed to Normandy). The anchor was subsequently attached to two coils of steel rope, shackled together and lowered over the stern and secured.

‘We maintained a high degree of vigilance overnight…we were drifting in the heavy swell and strong current. At first light, visibility had improved and through the binoculars, ships in the main anchorage were hull down. I found what I reckoned to be a destroyer and signalled ‘request assistance’. Shortly after a British Cruiser hove to…and started firing six or eight-inch shells over our heads towards some shore target. We had all had a gut-full of this, when a German fighter bomber dropped two bombs on the cruiser, both of which missed but one showered us with water. This sent the cruiser on its way. At this point the destroyer was…racing along at some 30 knots toward us…it was a Polish destroyer, manned by mainly British crew and under the command of an RN Lieutenant Commander. The crew of LCT 1038 was taken aboard, given a cooked breakfast and a shower to clean up. They were taken under tow and headed back to the main anchorage. Unfortunately, the kedge anchor from Portsmouth is lying off shore from Ouistreham. The salvage ship arrived on time and took us in tow to a quiet area, put a couple of powerful pumps aboard which reduced the level of water in the engine room quite considerably. A diver went over the side to inspect the bottom plate damage and at first light the next day work commenced…a quick drying cement box sealed the damage to the bottom plate and by the end of the day (June 8) LCT 1038 was floating at a normal level. Next day we were to head back to Portsmouth, towed by an American LCI and escorted by a second one. I had learned that the engine room crew were responsible for the dockyard kedge anchor incident so they were given the opportunity for making amends by spending the whole night of June 8 cleaning the engine room and getting some power back into the Paxman Ricardo engines. We left June 9 under tow and by early evening the engine room crew had managed to get some power back into both engines so I asked the LCI whether the tow rope could be slipped so we could proceed under our own power. At this time, we were about a mile off the Isle of Wight and found we could manage 5 knots. I certainly didn’t want to return to Portsmouth as our flotilla was to proceed to Weymouth after the landing and that was to be our base. We entered Weymouth harbour and berthed alongside the other LCTs of 51st Flotilla in the early hours June 10.’6

Following repairs LCT 1038 later supported landings at UTAH and OMAHA beaches shipping US troops and equipment. Bernie Nelson commented he had never seen such a mess as the edges of the channels of the two beaches were littered with abandoned tanks, guns and all sorts of armoured vehicles, many of which appeared undamaged.7 In 2005, Nelson received an award of the French Legion d’Honneur for his contribution to D-Day landings.

Sub-Lieutenant Peter Smith, posted as gunnery and watchkeeping officer to HMLST 237 travelled to United States to join his ship which had been built in Evansville, Indiana and sailed down the Mississippi to New Orleans. After trials and loading stores and equipment they sailed to Norfolk in August 1943 to join 4 LST Squadron and went in convoy across the Atlantic to North Africa. LST 237 was involved in many trips transporting British and American troops, trucks and tanks between Algiers and various Italian ports and also for the landing at Anzio in January 1944. In April – May 1944 they returned to UK and proceeded to Harwich on the east coast in readiness for the Normandy landings. On June 5, loaded with British troops, trucks etc they sailed in convoy with other LSTs and arrived off the beaches (GOLD) at 11 am on D-Day but did not unload the troops until the following morning. They were anchored alongside a British battleship firing salvoes over the beaches which, with each salvo, rolled the LST from side to side. They continued to transport reinforcements to the beaches until a steering problem resulted in a collision with the wharf at Southampton and a hole in the bow. After repairs they were directed to Appledore, North Devon for experiments in launching LCTs from LSTs. In late October Peter received a signal to return to Australia House, London for onward passage to Australia.

On commissioning, the experience of Sub-Lieutenant Theodore ‘Bluey’ Arthurs was similar to that of Peter Smith. In February 1943 he joined HMLST 430 at Baltimore where she had been built, and following working-up exercises at Norfolk in Virginia and then New York where they completed fitting out, they sailed in April 1943 in an eighty-ship convoy at about 8 knots for the Mediterranean. It took twenty-eight days from New York to Gibraltar! LST 430 had a cargo of trucks and jeeps and assorted stores but:

‘the really queer cargo was that on the upper deck…a US Navy type Landing Craft Tank (LCT) complete with its crew. Fastened to our deck were several large baulks of timber which ran athwartships and the LCT was secured to these with wire cables and shackles. We eventually got to Bizerta where this monstrosity was unloaded…this was done by inducing a list of about 30 degrees…by fiddling with our fuel and fresh water tanks. The aforementioned baulks of wood on which the LCT sat were plastered with grease and all the lashings and cables were removed until only one main wire held the LCT secure. One last shackle was freed by a hammer blow and in about 10 seconds the LCT was bobbing alongside’.8

In July 1943, during the invasion of Sicily, LST 430 was involved with carting troops and supplies from North Africa and then the landing at Salerno. Blue had been transferred to HMLST 420 in the same flotilla in late August 1943 and in late March 1944 was in Liverpool. For D-Day they left the Isle of Wight, arriving at 1000 hours at the beaches (SWORD) but waited for several days to unload. The ship had been fitted out to carry wounded, with a team of three doctors and numerous sick bay ‘tiffeys’ for the return trips to base in UK. The usual routine of back and forth with back-up troops, transport and supplies continued for some time.

Towards the end of 1944 Ken Dyson, Blue Arthurs and Peter Smith were posted back to Australia. Their experiences from D-Day ensured that they saw further service in South East Asia. (Ken Dyson was offered training as a beach master for the landing in Borneo but refused as he was a ‘bit sick of combined operations’ so he was sent up to Thursday Island to command a lugger with a crew of six Torrens Strait islander boys. They transported mine and demolition experts around the north coast of Australia).

Lyle Miller survived the sinking of HMS Somali in the Arctic seas, and following his officer training was appointed to HMS Scottish, a large heavily armed ocean-going trawler, to serve as an escort ship. After working-up trials in Tobermory,Scottish sailed to Milford Haven to collect a mixed assortment of coastal craft (HDs, MTBs, MGBs) for escort to the Mediterranean, presumably in anticipation of the Allied invasions leading up to D-Day. Weather conditions were severe and the convoy separated in the dense fogs; once arrived in the Mediterranean it was frequently under enemy air attack. It was some relief for Lyle to find that his next posting, from January 1944 to May 1945, was to HMS Sancroft. This was one of the two large converted cable layers in Force PLUTO (Pipe Line Under The Ocean) which was designed to supply petrol for the Second Front and the landings on D-Day. The steel pipe was laid from floating reels which were very tricky to handle as kinking had to be avoided at any cost. Sancroft laid an eighty-seven-mile pipeline from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg. Sub-Lieutenant Lyle Miller was the lowest paid man on board as the crew were merchant seamen in naval uniforms, all paid at merchant service rates, who certainly did not take kindly to naval discipline.

Lieutenant Guy Negus, a Fremantle enlistment, was recalled to the UK after two years on an HMDL based at Freetown, West Africa for convoy escort. He was posted to an Air Force rescue boat fitted with special electronic gear to ‘hopefully’ deceive the Germans about the location of the planned D-Day landings. He described it as: ‘an interesting exercise, and while based at the Mulberry harbour at Arromanches, we escorted many German prisoners back to the UK. As the war proceeded…we moved up the coast and I was given command of a small flotilla of HDMLs operating from Breskins in the Scheldt Estuary. Our task here was to deter German midget submarines and E-boats, which we did quite successfully despite inevitable shipping losses from mines. Our flotilla was responsible for the capture of the two-man crew of one midget submarine and the retrieval of another two-man crew with their submarine.’9

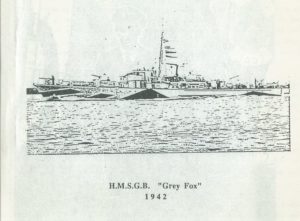

Following his commissioning from HMS King Alfred, Lieutenant Thomas John Scott was appointed Navigating Officer of Grey Fox (SGB 4) in the Steam Gun Boat Flotilla. From early 1944, the SGB Flotilla was busy in working-up exercises with landing craft with Combined Operations. On the night of 5 June, they sailed from Portland with an armada of landing craft and many larger ships, escorting them to Arromanches, off Gold Beach. Grey Fox was told to report to OIC American Destroyer flotilla, Western Task Force under Admiral Kirk, USN. The next day they were called to assist two hospital ships which had been mined as they wandered out of the swept channel. They stood by until tugs arrived to tow them back to England. Air Ambulance planes (DC3s) had to land on paddocks on the cliff tops to evacuate the wounded. For the next seven weeks they operated as a seaward screen for the destroyer squadron, about 15 miles to seaward to avoid the nightly raid on the anchorage. Storms, mines and rubbish

in the water meant that patrolling was not easy. The Commanding Officers of the six SGBs involved with the American Destroyer were subsequently invited to the American Embassy in London to be presented with the American Legion of Honour medal.

The service of the men included in this chapter is only an example of the ‘Yachties’ service involved in the invasion. Due to lack of accurate personal official records of many of the members of the Yachtsmen Scheme it is difficult to find just how many were involved in some way with D-Day. Their service is recorded according to the ships in which they served, not the theatres of war. Often the ship documented was in fact a shore base i.e. London Depot, HMS Copra. I was fortunate to be able to interview several of the men but I have had to piece together the details available from letters between the men in 1990s and the few reminiscences of service that some of the men wrote and made available to their families and friends in later life. Certainly, after the invasion and the hectic months following when so many of the ships were still involved in ferrying supplies and men to support the land component of the invasion, the Yachtsmen Scheme men were very busy. Their service in the ‘little ships’ of the RN had been achieved with acclaim in the UK. For most of the men, now aged in their mid-twenties, they had survived and established solid reputations for their seamanship, courage and daring. Quite a number had also achieved command. Most of them had served four years away from Australia without any home leave, and from October 1944 many were given passage back to Australia and the RAN, where they were subsequently involved in the landings in the South West Pacific and South East Asia to defeat the Japanese.

Importantly, several of the Australians involved in mine disposal were active clearing mines as the armies advanced. These men were attached to the ‘P’ Parties to work on underwater mine disposal, demolition and other diving tasks. Lieutenant George Gosse was awarded the George Cross for his work in clearing an oyster mine from the harbour at Bremen on VE Day, 8 May 1945. Lieutenant Commander Leon Goldsworthy defused several mines on the assault beaches as well as underwater hazards, for which he was awarded a DSC and Lieutenant Ernest Ruttle defused booby traps left by the retreating German army, thereby being awarded an MBE.

Other members of the Yachtsmen Scheme were also still serving in RN during 1945. For example, Lieutenant Clive Tayler was patrolling against U-boats in the Mediterranean and Aegean Sea in HMS/M Vivid until early 1945 when he was transferred back to Fremantle. Lieutenant Ted Gregg in LCI(L) was assisting the partisans along the Dalmatian coast in the Adriatic by landing supplies and bringing out the wounded. He was in Athens for VE day, 8 May 1945.

The success of the Normandy landings meant the Allies were able to consolidate their positions and continue to advance inland through France and subsequently Germany to defeat the Nazi regime. Eventually on 8 May 1945 victory in Europe was achieved. The whole exercise, from 1942 when it had first been conceived had been an amazing success in planning, coordination and cooperation between the Allied powers. The building up of a fleet of over 4,000 ships and the successful secrecy of the potential invasion over months and years of planning, had been a huge achievement, never seen before in world history. To have been part of this was highly valued by the Australians who had been involved. Unfortunately, when they returned to an Australia still on a war footing with the campaigns in the Pacific and South EastAsia against Japan, many of them received little understanding or recognition of their contributions in the war in Europe.

On the 75th anniversary of D-Day in 2019, while the Prime Minister and Chief-of-Navy were present at the commemorations at the beaches of Normandy, sadly there was no formal Commonwealth representation at the service at the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne. The other nations involved all those years ago were all represented by their consular officials and the national anthems of their countries were sung with the Australian anthem. This lack of acknowledgement for the men’s service at such a decisive operation in world history is very disappointing.

Notes:

1 Barnett, Corelli. Engage the Enemy More Closely: The Royal Navy in the Second World War Hodder and Staughton, London, 1991 p.781.

2 Ty constitutes Temporary in this official document. It was a legal requirement for temporary service as all RANVR men had volunteered only for the duration of the war (HO- for Hostilities Only). Subsequently some were offered permanent positions in RAN post war and would retain their officer status and promotions.

3 Interview with Lieutenant Ken Dyson 3 July 2008.

4 The ships, called ‘corncobs’ were ships which had crossed the Channel and then scuttled to act as breakwaters to create more sheltered waters at the five landing beaches. They became ‘gooseberries’.

5 The RANVR at the Invasion Pay Lieutenant-Commander JAB, RANR, HMAS Mk III. Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1944, 21.

6 Lieutenant Bernie Nelson, personal reminiscences of his service in RN.

7 When visiting Caen, fifty years later Nelson learned that much of the city had been restored after the war and paid for with some millions of dollars obtained from the salvaging operations carried out by French, mainly from these beaches.

8 Interview with Sub-Lieutenant ‘Blue’ Arthurs 30 August 2003. Personal reminiscences 28 June 1986.

9 Memoir of Lieutenant Guy Alfred Negus, undated