- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Janet Roberts Billett

Following the outbreak of war with Germany on 9 September 1939, the losses for the Royal Navy in ships and men through repeated U-boat and air attacks in the North Atlantic were horrendous and the odds against victory were all too obvious. In April 1940 the Admiralty approached the Dominions to recruit volunteers to be trained as temporary naval officers in the United Kingdom. The Royal Australian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RANVR) for Hostilities Only (HO) men were initially recruited through yacht clubs, hence the name. The first group sailed for UK in September 1940 in RMS Strathnaver. The ‘A’ Class candidates were aged between 30 and 40, intended for direct commissions in the RNVR and possessed a knowledge of navigation or equivalent required for the Board of Trade Yachtmaster’s (Coastal) Certificate; the ‘B’ Class candidates were between the ages of 20 and 30 and intended for entry into the RNVR as seamen, with the opportunity for later appointment as officers. Subsequently it is thought that another twelve groups were recruited. In all some 500 Australians served in the RN through the Yachtsmen Scheme.

RANVR Yachtsmen Scheme: contribution to D-Day – Operation OVERLORD

Following Dunkirk and the epic evacuation of British troops from Europe after France fell to the Nazi regime in June 1940, and it was obvious that Britain would have to fight very hard to regain a foothold in Europe against a highly organised and, at the time, technologically superior enemy with what would become impregnable coastal defences. The British, standing alone at this time and threatened by a German invasion, were determined to be ultimately successful in attacking and defeating them.

An attack such as this would involve huge technical problems; those of tactics, transport, and administration and the training of men from all branches of the Services in preparation for an all-out assault on the European mainland. It would also be necessary to develop a complete integration of thought, planning and experimental and executive action to avoid the inter-service rivalries that existed at that time. Combined Operations had been an original idea of Churchill and in June 1940, shortly after the evacuation at Dunkirk, he identified the need for a policy of raiding occupied territory organised through the Royal Marines. The problems of landing on a defended beach and the landing craft suitable and effective for this style of operation had been considered from before the war.

However, Churchill decided that this concept should be practicable and so, under his direction Combined Operations slowly developed and became of greater importance. New techniques and equipment for smaller operations such as raids and expeditions to destroy enemy installations, harass enemy shipping and assess enemy defences were developed and gradually put into operation. Naturally these would be clandestine operations.

Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten RN was promoted to Commodore and head of Combined Operations by Churchill in October 1941 and ordered to start a raiding program. The long-term aim was to prepare for an eventual invasion of German-occupied Europe. In March 1942 Mountbatten was given the position of Chief of Combined Operations with a seat on the Chief of Staffs’ Committee. Although much younger than the other Committee members and also of much lower rank, he had shown special qualities of daring and leadership when his ship, HMS Kelly was sunk in the Mediterranean and he was seen as suitable for the appointment. He was obviously highly intelligent with an understanding and knowledge of and knowledge of science and was keenly interested in scientific invention. He had prestige as a member of the royal family, and could work quickly and override obstructions if necessary. Most importantly, he could command loyalty from all ranks. Certainly those Yachtsmen Scheme men who served in Combined Ops and who had contact with him felt very privileged and proud to be associated with him. He was obviously very charismatic and personally recruited a high proportion of the men who served in Combined Ops. When recruiting newly commissioned officers, Mountbatten would suggest that next to serving in destroyers, the best thing was Combined Ops and since there were few vacancies in destroyers they ‘scooped the rest of the cream of the officer entry’.2 Apart from the fact that Mountbatten liked Australians, many of the ‘Yachties’ served under Mountbatten’s command as officers in the smaller vessels developed specifically for amphibious operations.

Bernie Nelson was one ‘Yachtie’ who served his sea-time in V&W-class destroyers. HMS Whitshed was put out of action by a magnetic acoustic mine which blew a hole in the engine room, so Bernie was then transferred to HMSCotswold, one of the Hunt Class destroyers. When he was newly commissioned and interviewed by a RN Lieutenant Commander, it was suggested that he should consider transferring to Combined Operations where there were many more opportunities for young officers, which he did. He became involved with intensive training in various types of landing craft with Army personnel, Commandos and Marines for several months. After that he joined several hundred others who were shipped to USA. He was appointed First Lieutenant of LCI 271 which was commissioned in New Jersey. The flotilla formed up at Norfolk, Virginia and then proceeded to North Africa where, from their base at Djidjelli they worked with Commando units and then trained with the 51st Highland division, Black Watch in readiness for the assault on Sicily. The headquarters for Combined Operations was set up in a series of terrace houses in Richmond Terrace between Whitehall and the Embankment and was known as a shore base, HMS COPRA (Combined Operations Pay Records and Accounts). The Royal Marines and Army Commandos were well represented and various groups included the naval Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPP), which did amazing reconnaissance work leading up to D-Day, the Chariot and X-craft Parties and the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD), a highly trained group for very ‘special’ clandestine activities. Special Operations Executive (SOE) was also included. It supported Resistance movements in enemy-occupied countries. A number of Australians, including Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers, were involved with these groups.

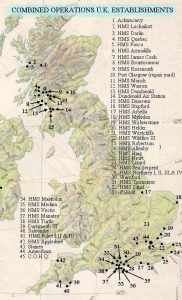

For Combined Operations, the magnitude of the task to train and equip an invasion force was huge. As a result, a total of 45 Establishments was set up in the west of Scotland and the south of England. The No 1 Combined Training Centre at Inveraray trained around a quarter of a million personnel in just four years, from October 1940 until July 1944, a month after D-Day. HMS Quebec was the RN establishment at Inveraray and its main role was to train men in ‘minor’ landing craft operations. HMS Dinosaur in the same area was the base for tank landing-craft training. Many of the Yachtsmen Scheme men, now young officers, spent time at these bases.

Many other newly commissioned Yachtsmen Scheme officers were trained at establishments in the north of Scotland at Fort William. There were three large and top-secret bases there; the main commando training facility was at Achnacarry with a remote location, rugged terrain and unpredictable weather. HMS Lochailort at Inverailort Castle was the school for boat officers. It was taken over by the RN in 1942 to meet the demand for training officers to crew the smaller landing craft needed for the invasion of Europe. Special Operations Executive men were also trained there. HMS Dorlin at Acharacle, Argyll was the third base, commissioned in March 1942 where training for RN Beach Signals

and the Royal Signals sections for battle training took place. Very tough assault courses which concentrated on natural and artificial obstructions were used and a variety of smaller vessels were available. ‘Opposed’ landing exercises were carried out on beaches mined by the Royal Engineers and with incoming live ammunition.

The first raid to take place following Mountbatten’s appointment was on Vaagso, an island off the coast of southern Norway where enemy shipping and some small industrial concerns were targeted. In February 1942 there was a raid on Bruneval in France for the capture of a German radar installation. This raid was also a first for Lieutenant Geoff Danne, trained at HMS Dorlin.2 He subsequently served in a number of Combined Operations Pilotage Parties in Italy, Sicily, Yugoslavia, Normandy, Burma and Holland. COPP was made up of Navy and Army personnel who reconnoitred beaches to obtain intelligence before a landing took place, carry out deception in enemy-occupied areas and then help guide the landing force ashore. They were aided by infra-red equipment, canoes and conventional and midget submarines. 3

In March 1942 there was a bold and courageous operation by Combined Ops to destroy the lock gates at St Nazaire. The huge dock at St Nazaire was the only dock in the world that could accommodate Germany’s latest and at that time most powerful battleship, Tirpitz. St Nazaire was situated some six miles up the Loire Estuary and was heavily defended by the Germans. The operation involved HMS Campbeltown, flying the White Ensign and packed with tons of explosives, which steamed towards the lock gates at 25 knots, aiming dead centre. The demolition commandos on board jumped ashore but few of them made it back to the waiting MLs. The firing mechanism in the Campbeltown, timed to explode after four hours, failed to do so but incredibly did so twelve hours later taking everything with it, including some three hundred German technicians. Despite the huge loss of life and ships (only three of the eighteen accompanying small ships survived), the raid effectively ensured that the largest ships of the German navy were contained for the duration of the war. First Lieutenant Bill Wallach RANVR of ML 270, the leading vessel, had taken command of the ship’s gun, a 3-pounder of 1890 vintage, with which he rattled away at one of the searchlights illuminating Campbeltown, a difficult task given the movement of the water.

I was down to about ten rounds, but I got it…she then had a clear run…straight to the gates and straight in. Once we put the commandos ashore, that was the end of them…We tried to pick them up but the boats were destroyed and the loss of life to the commandos was tremendous. 5

Interviewed at the age of ninety-three, Bill described the three hours of action as ‘hell’ but ML 270, with no steering, managed to limp back up the Loire Estuary before being abandoned and the crew picked up by HMS Brockelsby, the Royal Navy destroyer sent to aid surviving ships. Bill and the crew had survived one of the major special operations of the war, without significant casualties. He was subsequently awarded the DSC for his success in knocking out the searchlight, ensuring that the commandos were landed and the Campbeltown assisted to reach the lock gates.

In August 1942 the disastrous Dieppe raid was launched. The raid had originally been planned for July but was called off due to unfavourable weather conditions for landing troops on the beaches around Dieppe. Keith Nicol was wounded in the first aborted operation with burn and blast damage from the ship astern, when it kept firing after a successful pass on a German E-boat. He was landed back at Dover at daylight and ‘was helped ashore by Mountbatten himself, a most humble and gracious man’.5 Keith subsequently missed the raid as he spent about ten days in hospital.

The other sailors involved had been informed of the place and nature of the raid already and were sent on ten days leave in the interim. Doug Gilling6 who was doing his sea-time in HMS Berkeley, can still remember the looks of horror on the faces of his shipmates when it was announced by their CO that ‘this time it’s for real’ – obviously, on leave, they had not all been discreet about the events in July.7 When the same ships and personnel were regrouped off Portsmouth in August, the men had no doubt that the Germans would be ready for them.

Dieppe was the largest combined operation to take place at this time and involved a total of over 6,000 troops composed of two Canadian infantry brigades and Royal Marine Commandos, plus a tank battalion and some US troops. The Royal Navy provided eight destroyers in support and ferried the troops to shore by landing craft. Several ‘Yachties’ were involved in the supporting ships. Doug Gilling survived the sinking of the Berkeley, one of the Hunt-class destroyers. He had been one of a gun crew supporting the landing. A shell destroyed the wardroom which had been temporarily converted into a casualty ward for injured Canadian soldiers. None of these survived. What was left of Berkeley was sunk shortly after by torpedoes from her sister ship. After about 10 minutes in the water Doug was picked up by a landing craft and taken to a sister ship in the D1 flotilla where he resumed his duties, lately suspended in Berkeley,of being an ammunition load number on its aft twin 4-inch turret.8 Other ‘Yachties’ in action at Dieppe were Cyril Masterman, Jack Scott, Frank Appleton and Tom Foggitt. Harry Brownell from Hobart was killed in action there and Patrick Landy was taken prisoner. The operation was a costly failure especially in the lives lost – the Canadian mortality rate was 68 per cent. But valuable lessons were learned in relation to the tactics and techniques necessary for an amphibious assault on a heavily defended coastline.

In January 1944 Lieutenant Lloyd Bott was posted as First Lieutenant to MGB 502 in Dartmouth. The 15th Motor Gun Boat Flotilla was the communication link between France and England on Intelligence, mainly working with SIS (Secret Intelligence Service including MI5 and MI9) and SOE. The MLs were special as they were the only high-speed diesels the Navy had. In the six months leading up to D-Day in June 1944, Lloyd was involved in twelve trips across to France, always undertaken on moonless nights. Fellow ‘Yachties’ based in Dartmouth never believed he went to sea. Given that sailings were timed to remain outside 30 miles of the enemy-occupied French coast until two hours after sunset, which in February would be about 1530 hours, this could mean sailing from Dartmouth early afternoon. Either Lloyd’s fellow ‘Yachties’ were not very observant or were being deliberately provocative in their comments! In one of the operations, 26-27 February 1944, Lloyd Bott was in charge of the surf boats to land two agents, one of whom was Francois Mitterand (later president of France 1981-95) who at the time was a member of the Resistance movement ‘Liberation-Nord’. 9

Once close in shore in Brittany, radio contact was made or an agreed Morse letter flashed from a hand-torch. The MGB anchored off shore and the landing party rowed in with muffled oars in a surf boat which had been newly designed for the purpose. This exercise was very difficult as the journey between the mother ship and the shore was in complete darkness, against the strong tidal streams of the Brittany coast, frequently onto a lee shore and a coastline strewn with jagged rocks. In July 1945 Lloyd was awarded a DSC for his work in this covert theatre of war.

Lieutenant Kenneth Uhr-Henry, another Yachtsmen Scheme volunteer from Hobart, also served in 15th Motor Gunboat flotilla, in MGB 318. In early December 1943, Uhr-Henry was in charge of one of three of the gunboat surf boats, when a third attempt was made on the Brittany coast to rescue stranded Allied airmen who were waiting on Île Tariec. With the weather deteriorating rapidly, he was told to rescue the 20 evaders, unload stores and return to the waiting MGB as fast as possible.

MGB 318 suffered damage to her gun buzzers and navigation lights and by 0428 decided that they could wait no longer. As they made to weigh anchor, one of the surf boats was sighted astern, making no progress in the huge seas. All available hands dragged the men out of the surf boat and finally pulled it on board. As they looked back at Île Tariec a red lamp was seen flashing from the island indicating that others had survived the ordeal. MGB 318 arrived back in Falmouth 25 hours after sailing. In fact, one of the other surf boats had sunk and the other one capsized in the mountainous waves but all aboard were able to get back to the beach and were hidden until three weeks later when they were successfully taken off the same beach by MGB 318. Uhr-Henry did twelve successful missions with MGB 318 across to France and in May 1944 was awarded a DSC for services while engaged in special operations.

Another Yachtsmen Scheme officer, Lieutenant Ivan Carlyle Black from Sydney, was involved in similar work and was captured by the Germans in early 1942 when his boat capsized in heavy surf on landing.

By early 1944 most of the Yachtsmen Scheme volunteers were trained as officers and experienced in the ‘little ships’ for which they had been recruited. Many had already achieved command and others were involved in various vessels essential to the continued effort to defeat the enemy. They were spread around the Royal Navy and only a small number, those in the larger ships, were lucky enough to be serving with fellow Australians. After nearly four years away from home they were about to serve in one of the most momentous military attacks in world history – the Normandy landings in June 1944.

1 Philip Zeigler, Mountbatten (New York: Harper and Row, 1986), 162.

2 Mrs Elizabeth Danne, interview 19 April 2003.

3 Bear, I. C. J. (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 1995), 256.

4 Lieutenant Commander Bill Wallach, interview 1 May 2002.

5 Lieutenant Keith Nicol, interview 17 December 2001.

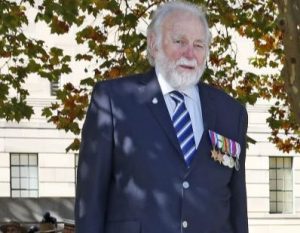

6 At the time of writing, Doug Gilling (now aged 98), is to my knowledge the only Yachtsmen Scheme officer still alive. He lives in the Blue Mountains and travelled to Canberra in May 2017 to unveil the commemorative plaque at the Australian War Memorial.

7 Lieutenant Doug Gilling, letter to Cyril Masterman 9 March 1999.

8 Lieutenant Doug Gilling, letter to Cyril Masterman 9 March 1999.

9 Lieutenant Lloyd Bott, CBE, DSC: The Secret War from the River Dart: The Story of the Royal Navy’s 15th Motor Gunboat Flotilla 1942 1945, (The Dartmouth History Research Group 1997), 24.

Part 2 of this series will be published in a future edition of this magazine.