- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Royal Navy

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Cdr Mike Channon RN

This article first appeared in the Royal Navy Instructor Officers’ Association magazine RNIOA No 24 dated 22 November 2023 and is reproduced by kind permission of the author and editor of that magazine. As the Fastnet race and our Sydney to Hobart have many similarities the lessons learned here are of interest.

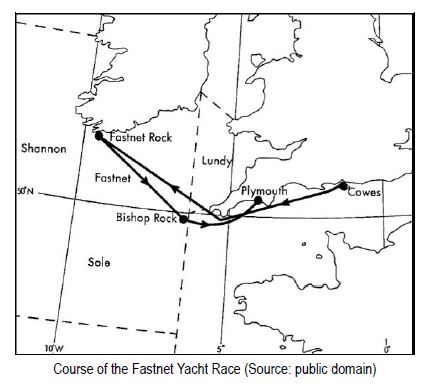

In August this year, I watched a Channel 5 TV documentary on the disastrous Fastnet Yacht Race of 1979. Thatdocumentary was of particular interest to me as I had been the RN duty weather forecaster at Northwood from 0700 to1900 on the 13th of August, which was just before the worst of the storm hit the racing yachts overnight on the 13th and14th of August. Fastnet races are biennial events that happen in August every other year and organised by the RoyalOcean Racing Club (RORC) in conjunction with the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) based at Cowes on the Isle of Wight.

As the RN duty forecaster at Northwood, my responsibilities included producing weather warnings and the RN Shipping Forecast. During the early afternoon I started noticing unusually large pressure falls in the Fastnet area, reported by ships and shore observing stations, and decided to issue a Gale Warning for the relevant shipping areas. If the RN intended issuing a Gale Warning before the UK Meteorological Office (UKMO), we were compelled to inform their duty forecaster, which I duly did. During that telephone conversation, the UKMO forecaster informed me that their numerical models were not forecasting gale force conditions. However, we had no access to those models at Northwood, though we did see UKMO forecast charts which were derived using them.

At that stage their forecast charts were not particularly pessimistic. Considering the observed pressure falls takingplace, I went ahead and issued Gale Beaufort force 8 (34-40 knots) warnings for Sole, Shannon, Fastnet, Lundy andPlymouth anyway. The barometric pressure carried on plunging, and despite no received wind observations showinggales yet, I raised the warnings in the Sole, Shannon, Fastnet and Lundy areas to Severe Gale 9 (41-47 knots),amending the RN Shipping Forecast accordingly. I cannot recall the exact time I issued the warnings, but I doremember that the UKMO had still not issued a warning at that stage which caused me a little concern that my ownforecasts might be incorrect. Those fears proved groundless when Ocean Weather Ship (OWS) Romeo1 in the SWapproaches started reporting gale force winds at 1500.

According to the Fastnet Race Inquiry Report, the UKMO issued its first Gale 8 warning at 1505. I turned over thewatch to my successor at 1900 and, with pressures still plummeting, he immediately issued Storm Force 10 warnings(48-55 knots). The UKMO’s first warning mentioning Force 10, however, was not broadcast until 2245. The difference for the RN was that we had no access to, and therefore were not distracted by, the output of the rather primitive numericalmodels of that time. We had used simple ‘seat of the pants’ forecasting techniques based on observed pressure changes (Iremember conducting isallobaric analyses2 that day) and reacted accordingly.

Although it may have been somewhat professionally satisfying that the RN had issued warnings earlier than theUKMO, those warnings and our more pessimistic shipping forecasts were only received by naval vessels and therefore not received by the yachts. Even if they had been, it would have been far too late to have made any difference as thevessels were already in the danger area with insufficient time to run for safer waters. The low-pressure system thatcreated the havoc had undergone what meteorologists call ‘explosive’ cyclogenesis or deepening, defined as apressure fall of 24 millibars in 24 hours. Today it would probably have been described as a ‘weather bomb’. Duringthe day of the 14th, while the rescue effort was in full flow, the overnight forecaster and I were recalled to the RNFleet Weather Centre at Northwood for an internal investigation, which generally concluded that we had issued ourwarnings and forecasts correctly based on the information available and in a timely fashion.

Accurately forecasting the Fastnet storm of 1979 in sufficient time to enable cancellation or postponement, wouldalmost certainly have been impossible back then. Ideally, the RORC would have required an accurate assessmentbefore the 11th of August, some 72 hours before the severe gales arrived, yet even days later the UKMO forecast modelswere underestimating its strength. This is hardly surprising as relatively limited satellite data were available back then, andthe low resolution of the numerical forecast models used reflected the lesser ability of the computers of the time.

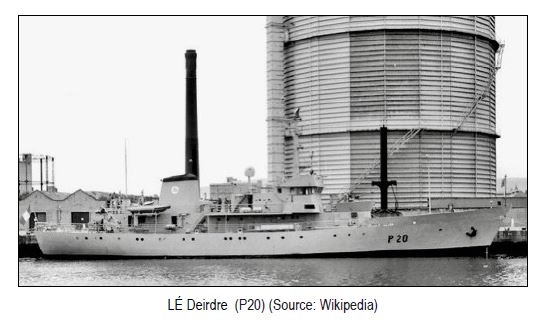

The UKMO global model had a very coarse-mesh 300 km grid spacing and only 10 vertical layers. Even its limited-area or fine-mesh model only had a basic 100 km grid spacing. This meant they were unable to cope with such an event. Based on those models, the BBC Shipping Forecast on the afternoon of the 13th of August, as compiled by the Meteorological Office, was forecasting winds of Force 4, increasing 6 to 7, locally Gale 8, for the race forecast area. Most ocean-going yachts would have coped with those forecast conditions quite comfortably. However, the reality was that overnight on the 13th/14th August 1979, Storm Force 10 winds were being recorded. The Irish Naval Patrol vessel LÉ Deirdre observed Severe Gale 9 at midnight and Storm Force 10 by 0300. Fastnet Lighthouse reported Beaufort Force 9-10 between 2300 and 0400 then slowly subsiding to Gale 8 by 1100 on the 14th. Some of the race participants estimated peak sustained winds had reached Violent Storm Force 11 (56-63 knots) but this was not independently verifiable at the time.

The effect of this storm on the race participants was catastrophic. Of the 303 yachts that started the race at least 75 capsized, 24 were abandoned and five were lost, believed sunk. Tragically, 19 people (15 participating yachtsmen and four spectators aboard Bucks Fizz, a yacht shadowing the fleet to view the race) lost their lives. The death toll would have undoubtedly been greater, except for the incredible rescue process and the speed at which it was initiated.

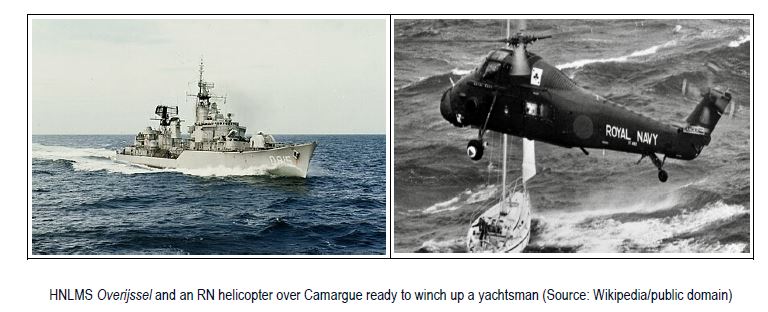

Naturally, the RN was heavily involved with HM Ships Broadsword, Anglesey and Scylla participating in the rescue mission as well as RFA Tidespring. Additionally, the Dutch ship HNLMS Overijssel, which was the designated Duty Guard Ship for the race, played an important role.

Fifteen helicopters from RNAS Culdrose were committed. Anyone with Search and Rescue (SAR) experience was recalled, and extra helicopters and crews were sucked in from other naval air bases including Yeovilton and Prestwick. Alongside the navy were 14 RNLI lifeboats which rescued yachtsmen and towed damaged yachts back to port. Three RAF helicopters, seven warships, including the Irish LÉ Deirdre and USS Holland, a submarine tender operating out of Holy Loch, as well as four trawlers and four other vessels were supporting the effort, while overhead four RAF Nimrods helped to coordinate the search effort over 10,000 square miles of ocean. In all, around 4000 military and civilians were involved in the huge rescue effort which picked up a total of 125 yachtsmen between Land’s End and Fastnet.

Analysis of the 1979 Models and Forecasts

Would today’s numerical models, using the data of Fastnet 79, have done any better? One would certainly imagine so, but before considering that question we need to look in a little closer detail at how the models of the time performed and the forecasts resulting from them. The Meteorological Magazine No. 1311, Vol 110 published in October 1981 contained a review of the storm from a UKMO forecaster’s perspective. Some of the following information was taken from that review.

Would today’s numerical models, using the data of Fastnet 79, have done any better? One would certainly imagine so, but before considering that question we need to look in a little closer detail at how the models of the time performed and the forecasts resulting from them. The Meteorological Magazine No. 1311, Vol 110 published in October 1981 contained a review of the storm from a UKMO forecaster’s perspective. Some of the following information was taken from that review.

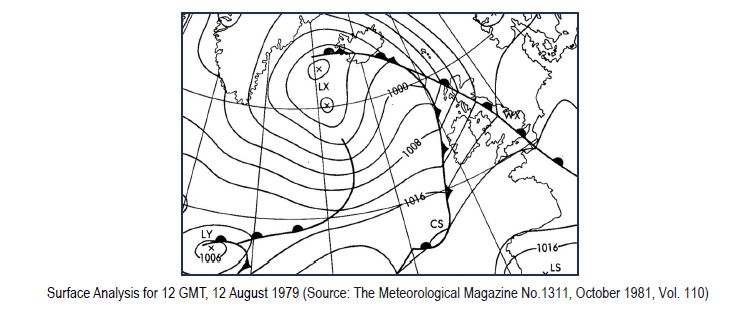

Today the Fastnet 79 storm would have been given a name, but back then it was merely known as Low Y (LY). The isobaric weather chart at left shows the Surface Analysis produced by the UKMO Central Forecasting Office (CFO) at Bracknell for 1200Z on the 12th of August 1979.

Today the Fastnet 79 storm would have been given a name, but back then it was merely known as Low Y (LY). The isobaric weather chart at left shows the Surface Analysis produced by the UKMO Central Forecasting Office (CFO) at Bracknell for 1200Z on the 12th of August 1979.

This would be the latest time to determine the race (already underway) forecast and allow the race organisers to decide whether competitors should be warned or recalled assuming there was a satisfactory method of contacting them. The relatively shallow Low Y can be seen in the bottom left in the waters east of Newfoundland. The UKMO 10-level coarse-mesh model at that stage was predicting LY running rather quickly eastwards at about 30 to 35 knots during the first 48 hours with little or no development. The RORC, as race organisers, had asked Southampton Weather Centre for an extended forecast to be prepared at 0700 on 11th of August, about seven hours before the start of the race, with an outlook until midnight on the 13th of August.

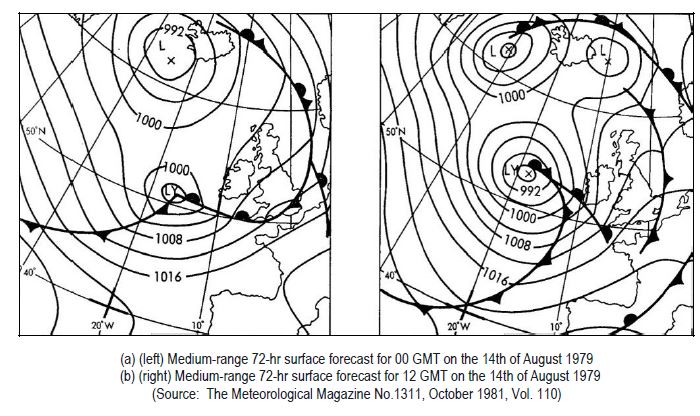

This allowed the RORC to pass the information to the yachts prior to the start of the race (1350). The RORC made no arrangements to receive updated forecasts during the race because they had no means of transmitting the information to the competitors, who mainly relied on the BBC shipping forecast, compiled by UKMO, once they had sailed. At the final briefing, which took place shortly before the start of the race, again after consultation with the CFO at Bracknell, the possibility was indicated of winds reaching gale force (Beaufort force 8) at times from Tuesday the 14th of August onwards. The charts (a) and (b) at right were not available until after that briefing. The models were still underestimating the deepening of the low, a known deficiency, and so the forecasters preparing charts (a) and (b) had subjectively deepened the low by 12 mb more than the model was predicting. This also proved to be a considerable underestimation. It is worth mentioning that on the 12th of August, a forecast prepared by Southampton Weather Centre for Offshore Instruments Ltd in connection with the Fastnet Race included the possibility of severe gales (Force 9) on the 14th, in line with the medium-range guidance and outlooks issued from the CFO. However, the shipping forecasts, which were the main source of weather information for the yachtsmen, contained no such information since the major intensification of LY was expected to take place after the 24-hour period covered by the forecast.

A summary of the conclusions concerning model performance as published in the 1981 Meteorological Magazine is shown below.

- a) Guidance for 48 and 72 hours ahead from the coarse-mesh 10-level model gave firm indications that low LY was likely to deepen as it approached western Ireland, but the surface pressure forecasts seriously underestimated the amount of deepening by a huge 20-25 mb.

- b) Limited area model forecasts for 24 and 36 hours ahead also failed to give advance warning of the sudden deepening and exceptional vigour of the low. Forecasts of the depth of LY at the peak of the storm were generally in error by 20 mb or so.

- c) The 24-hour subjective forecasts by UKMO forecasters, for the period when the storm was at its height, showed some improvement over the corresponding limited-area model product.

Even so, forecast winds in the race area were still severely underestimated at this stage.

A summary of the timing and warnings provided by the UKMO and broadcast by the BBC on Radio 4 for the 13th of August, as published in the 1979 Fastnet Race Inquiry Report is shown below. It needs to be noted that generally competitors did not continually monitor Radio 4, most just tuning in for the shipping forecast at known set times. Wind warnings that were broadcast as available and not at standard times were therefore of limited value as they were mostly missed.

1355: Shipping Forecast indicated strong winds, force 6-7 for a limited time.

1505: Gale Warning (Force 8).

1750: Shipping Forecast of winds ‘locally’ gale force.

1830: Severe Gale (Force 9) warning.

2245: Storm (Force 10) warning.

0015: (on the 14th of August) Shipping Forecast mentioned Force 10 (by which time many of the yachts had already experienced such conditions).

The above analysis clearly shows the UKMO forecast models of 1979 were incapable of predicting the Fastnet storm quickly enough for the organisers to make lifesaving decisions. The UKMO forecasts severely underestimated the rapid development of the depression and its associated wind strengths. Their eventual Storm Force 10 warnings were far too late. In essence, the science of 1979 was inadequate for this situation.

A Comparison with Today’s Models

So, how would today’s numerical models cope with the same data available to the UKMO in 1979? Fortuitously, in 2019, a group of meteorologists at Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD), the German Meteorological Office, based in Offenbach, decided to mark the 40th anniversary of Fastnet 1979, by carrying out a re-forecast using the data of 1979 with current numerical models. Information on this re-forecast was published in the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Newsletter 161 in Autumn 2019. The re-forecasts by DWD used one of the modern icosahedral non-hydrostatic (ICON) models. The ICON model used had a grid spacing of 13 km and 90 vertical layers, a far higher resolution than the two models used in 1979, which had grid spacings of 300 and 100 km respectively and only 10 levels.

Unsurprisingly, the German ICON model and the vastly superior computers that could run it, gave a very good 72-hour prediction of the surface pressure and wind conditions albeit some two to three hours later than the actual occurrence and with a slightly displaced depression centre. Even with these minor discrepancies, the forecast conditions for the race were very close to those which occurred and would have resulted in postponement of the race.

A similar re-forecast run by the University of Dublin and the Irish Centre for High‐End Computing (ICHEC) using their own models produced similar results, including confirming the Force 11 winds that many race participants claimed to have experienced but which could not be verified at the time.

In summary, the 72-hour re-forecasts from both DWD and University College Dublin and ICHEC captured the essential details of the storm, which is indicative of the huge progress made in numerical weather prediction. Had such models, and the computers to run them, been available in 1979, the race office would have undoubtedly reacted to the forecasts and postponed the event until the system had passed through, as happened in 2007 when the race was delayed by 25 hours due to adverse weather conditions.

This article set out to determine whether the Fastnet 79 Race disaster would have occurred today. The analysis provided indicates that it would be most unlikely. Of course, extreme weather will always cause disasters somewhere in the world, but almost certainly not for events like the Fastnet Yacht Race where meticulous planning and support are provided. Superior forecasting models and techniques, vastly improved telecommunications, mobile devices and a plethora of weather apps, not to mention advances in yacht design and safety, make it almost impossible that such a disaster could occur in modern times. Today, yachtsmen and sailors can rest easy and have a high degree of confidence in warnings and forecasts issued by the UKMO.

1 Ocean Weather Ships were stationary ships in set locations that gave accurate hourly weather reports and released weather balloons four times a day. They were considered accurate meteorological information collectors in data-sparse areas, but the running costs of these vessels became prohibitive, and they were discontinued in the early 1980s.

2 Isallobars are lines of equal pressure changes during specified time changes. Traditionally isallobars of falling pressure changes are superimposed on normal isobaric charts as dashed red lines.

References

1 Wikipedia 1979 Fastnet Race (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1979_Fastnet_Race)

2 The 1979 Fastnet Race Inquiry Report (https://keyassets.timeincuk.net/inspirewp/live/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2019/07/fastnet-race- inquiry.pdf)

3 The Meteorological Magazine No. 1311, October 1981, Vol. 110. The Fastnet storm – a forecaster’s viewpoint by A. Woodroffe (Meteorological Office, Bracknell)

4 European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Newsletter 161 (https://www.ecmwf.int/sites/default/files/elibrary/102019/19263-newsletter-no-161-autumn-2019_1.pdf)

5 Met Éireann, Ireland’s National Meteorological Service