- Author

- Date, John C., RANVR (Rtd)

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Canberra I

- Publication

- September 1989 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

On the 8/9 August, 1942, a controversial naval battle took place in the Solomon Islands, South West Pacific. It was a rebounding success for the Japanese and a tragic loss to the Allies of four heavy cruisers sunk and considerable damage to other ships resulting in the loss of over 1,000 navy men and with over 700 wounded.

The Japanese admiral took a gamble to attack at night and was to be most surprised with the good fortune that worked in his favour.

The episode began with the first amphibious operation by American ground forces in the retaking of Japanese occupied territories at points of Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands which was covered by an Allied naval force to protect the transports and landing beachheads.

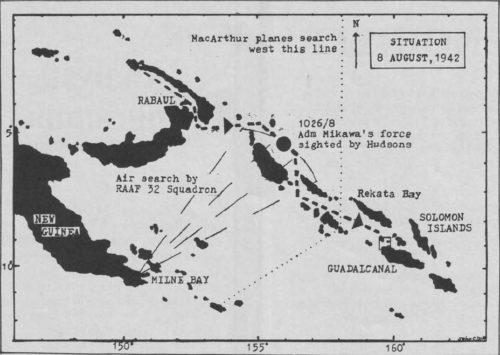

A strong Japanese force of cruisers had spent the previous day in travelling south from the Rabaul area and in the early hours of the morning of 9 August, 1942 swept round Savo Island, passing between the picquet destroyers Blue and Ralph Talbot both equipped with radar that failed to detect the enemy force, although the Japanese had the destroyers under surveillance. They then surprised the first Allied cruisers, hitting HMAS Canberra which was later to sink and badly damaging the USS Chicago, and continued on to catch unawares, and engage, a second Allied cruiser force consisting of USS Vincennes, Quincy and Astoria, causing the loss of the three cruisers and damage to US destroyers, without any loss to the Japanese ships.

On the immediate scene, some warning was given by the sighting and reporting of Japanese observer planes flying overhead, and by the US destroyer Patterson of unknown ships entering the harbour, but the Allied ships were presumably not prepared to accept the reality of the situation. Individual ship commanders were aware of the Japanese as being within striking distance of Savo Sound and so without the necessity of further direction from their admiral, it was their responsibility to be prepared for any eventuality.

The American historian Samuel Eliot Morison writing ten years after the event (1), named ‘unfortunate circumstances’ for the debacle, one being the lack of communication from a Royal Australian Air Force Lockheed Hudson aircraft A16-218 of 32 Squadron operating out of the Fall River Base, Milne Bay in New Guinea to the sighting of the enemy force at 1026/8 August. Morison went on to say (2) that failures in ship identification and communications were ‘enough to explain why Vice-Admiral Gunichi Mikawa managed to make his approach undetected’. In reality, Morison was stating that the pilot of the Hudson Sgt W.J. Stutt failed to break radio silence, did not return directly to his base with the vital information that he had sighted an enemy force approximately 150 miles from Rabaul but spent the next few hours on reconnaissance and on landing having tea before filing his report. The advice given to Morison appears a misrepresentation of the true facts and now other writers are similarly laying the blame against the lack of reporting from the Australian Hudson plane as the first mistake in a battle of many errors and therefore the main contributing reason for the Savo Island battle disaster.

This is most unfortunate and is entirely incorrect, being at variance to the true facts.

In order to show that Stutt did broadcast an immediate enemy report, a great deal of exhaustive research was undertaken by W.F. Martin Clemens, who is a Companion of the United States and the coastwatcher hero on Guadalcanal; Mrs Lloyd Milne the wife of the pilot of a second Hudson that sighted Mikawa 35 minutes later, and who by checking reports preserved in the Library of War History, Department of the Naval Defence College, Japan, listed the equivalent time of 1027 as receipt by Mikawa of Stutt’s radio message; G. Herman Gill who prepared the Official History of the Royal Australian Navy 1942-45 (published in 1969); and A.J. Sweeting, General Editor of Official War History.

The findings have been most ably presented in a paper by Captain Emile L. Bonnot USNR (Ret) in 1988 (3) stating that ‘Stutt’s radio message from the Hudson plane had been received by the following:

- USS Vincennes in that Captain Reifkohl the Commanding Officer made mention of it in his orders on the afternoon on 8 August

- USS Astoria as Lt.Cmdr. Walter B. Davidson said he had a report in the morning

- USS Enterprise by Lieut and Assistant Gunnery Officer Elias B. Mott saying the report was placed on their Status Board in the early afternoon

- HMAS Canberra with Cmdr. E.J. Wright, control officer of the after 8” guns, stating that they had the report when he came off watch at sunset

- MacArthur’s SW Pacific Area Headquarters Station Report No. 350 1817/8 repeated over Bells radio and read by Rear Admiral V.A.C. Crutchley at 1839/8, repeated over Fox radio and read by Rear Admiral R.A. Turner at 1845/8,

and incredibly logged by Mikawa the Japanese admiral at the stated time of transmission.’