- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, Influential People

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Doris Shearman

‘I Think It’s Gonna Be a Long Long Time’ – from Elton John’s 1972 iconic song ‘Rocket Man’ about an astronaut preparing for a space mission.

Introduction

For those of us lucky enough to live long lives we have a memory span of say eighty or so years. But we can remember parents and grandparents with first-hand knowledge of events going back much further. We often think about wars and revolutions where anniversaries of victories are celebrated but these can also represent misery and destruction. Truly magnificent events are celebrated in arts, literature and science. Thankfully the great artists, composers, writers and scientists also flourished during times of conflict. Great technological advances were made when steam surpassed sail and the horse was replaced by horse power.

Even more excitingly, man conquered the air in flying machines and lives were made much easier with the supply of electricity providing light and power, the telephone allows instant communications, and we now have radio, television and computers to enrich lifestyles. But to my mind the greatest single achievement during this time, that epitomises and harnesses the above great advances, occurred just over fifty years ago on 16 July 1969 when man first stepped onto the moon.

Race to the Moon

In many respects the race to the moon started with ‘Operation Paperclip’ a secret United States program to gain advantage over the Soviet Union by taking 1600 German scientists, engineers and technicians to the US immediately after the end of WWII. These were from those involved in the development of synthetic materials, advanced medicines and weapon systems which included rocket technology. Naturally the Soviets responded by taking a similar number of Germans with identical skills into their homeland.

For eternity the wonders of the moon, the brightest object in the night sky, have fascinated mankind. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Agency was established in 1958 and with this the space race to unlock the moon’s secrets began. It was made all the more imperative to national prestige when on 25 May 1961 President Kennedy boldly challenged America to commit to the goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade.

The original Deep Space Network comprised three stations roughly separated by 120 degrees of longitude, thereby equally covering the Earth’s surface. The first and master station was established at Goldstone near Barstow, California; next in 1960 came Island Lagoon at Woomera in South Australia, and finally in 1961 Hartebeesthock near Johannesburg.

With advances in technology these needed to be upgraded. Upgrades were already in place at Goldstone but political concerns in South Africa called for a new station, on the same longitude, to be built at Fresnedillas near Madrid, which opened in 1965. Problems attracting staff to remote Woomera led to another station being built at Tidbinbilla near Canberra which also opened in 1965.

Space flight required an immense propulsion system, provided by German rocket technology that had been brought to the United States after WWII and developed by a large team led by Wernher von Braun. The successful V2 rockets manufactured in WWII could cover a distance of 128 miles (206 km). These were the forerunners of the massive three-stage Saturn V rockets which had to cover a combined distance of about 238,000 miles (382,900 km) to reach the moon, and then the lunar module had to return over the same distance. It has been said, perhaps unkindly, of von Braun that he liked building rockets, but was not too fastidious about for whom, or where they landed.

Saturn V rockets launched from the John F Kennedy Space Centre in Florida were so tall they would dwarf both the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower. On lift-off they weighed 3200 tons and reached speeds of 5500 miles per hour. The projected moon landing was termed the Apollo Mission, which began on 27 October 1961 with Apollo 1 and concluded on 7 December 1972 with Apollo 17.

A vital part of the Apollo Missions was the ability to communicate with and track the space craft. The astronauts and Mission Control in Houston, Texas could maintain continuous two-way communications by relaying through tracking stations.

Australian Stations used in Moon Landing Projects

As Australia is in the opposite hemisphere to North America it provides a unique situation when the United States is seeking to gain global coverage for space exploration. The wartime interaction between Australian and American forces also cemented a favourable impression of reliability. Added to this was the recent Anglo-Australia experience through the establishment of the Weapons Research Establishment (WRE) at Salisbury and the Woomera Rocket Range, both in South Australia. Additionally, in 1958 a nuclear reactor was commissioned at Lucas Heights on the outskirts of Sydney, and a nuclear power station was proposed to be built at Jervis Bay. Sixty years ago the relatively young nation of Australia was really at the forefront of cutting edge technology.

An early American station was at Brown Range near Carnarvon in WA with a 30-foot (9 m) dish, commissioned by NASA in 1964, which was the largest such facility outside the US at the time. While it operated until closure in 1975 its functions were gradually replaced by a new facility at Honeysuckle Creek near Canberra. Surprisingly the pocket-handkerchief sized Australian Capital Territory could boast of three space facilities located in close proximity; Honeysuckle Creek, Orroral Valley and Tidbinbilla. Although these new stations supported American programmes, they were manned by Australians.

Tidbinbilla

As a replacement for Woomera, In March 1963 NASA leased 150 acres of farmland in the Tidbinbilla Valley 40 km southwest of Canberra in order to build an 85-foot (26 m) diameter dish and its associated deep-space tracking equipment.

Orroral Valley

NASA next built a satellite tracking station not far distant in the Orroral Valley, home to an 85-foot (26 m) antenna which commissioned in 1965. Signals received from satellites in Earth orbit are relatively strong but viewing periods are short, requiring frequent switching between stations to improve coverage. By 1965 the station became one of the largest and most capable in the NASA network with a capacity to track up to 30 satellites, gathering information on atmospheric temperature and pressure between 500 and 2000 miles above Earth. The station became obsolete and was closed in 1985 when the antenna was transferred to the University of Tasmania.

Honeysuckle Creek

The third tracking station in the ACT high country was at Honeysuckle Creek with an 85-foot (26 m) antenna, officially opened on 17 March 1967. Honeysuckle became the main NASA tracking station in Australia for the manned Apollo missions and coordinated the tracking effort between other NASA stations and Parkes.

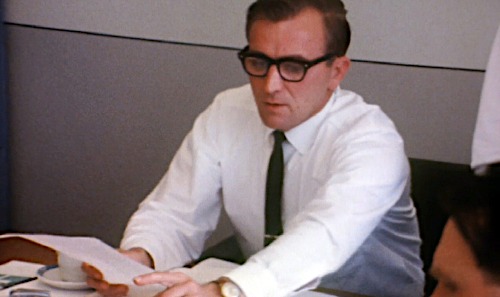

The new director was Bryan Lowe, a dapper and personable 38-year-old electrical engineer. In 1947 he had joined the Royal Navy as a Radio Mechanic and after naval service migrated to Australia, working at WRE Salisbury. During the Apollo missions Tidbinbilla acted as Honeysuckle’s wing station, providing full back-up and sharing the load. The importance of these three stations should not be underestimated as before countdown on an Apollo launch each of the three stations had to be in a state of ‘green light readiness’; if not, the engines of the Saturn V rockets would not ignite. To keep the stations active while waiting for an actual attempted moon landing, simulations were conducted. Locally this was done by flying an aircraft back and forth over the Brindabella Mountains.

Parkes

In 1961 CSIRO commissioned a large radio telescope at Parkes in NSW which remains in use. This station was designed for astronomy and while it can receive signals from space it is unable to transmit. The innovative design of its dish antenna with a diameter of 210-feet (64 m) became the model for other large antennas of NASA’s Deep Space Tracking Network.

A limiting feature of Parkes coverage was the fact that its dish could only be angled from 30 degrees above the horizon. This intentional design feature allows the observation of the South Celestial Pole, a portion of the sky not well covered by other radio telescopes. A successful 2000 film The Dish is based upon actual events that took place at Parkes but with some historical inaccuracies to improve the dramatic effect.

Anticipating that additional support might be needed by the ACT stations during Apollo 11, assistance was requested from John Bolton, the CSIRO director at Parkes. Although Parkes had no transmitter and could not send signals to spacecraft, the size of its 210-foot dish enabled it to receive more of the lunar module’s weak downlink signal, permitting it to enhance the quality of the data passed to Mission Control. During the all-important Apollo 11 lunar phase the Australian stations now comprised Honeysuckle, Tidbinbilla and Parkes, with Honeysuckle being the hub of the network.

Some Personalities – Meet Tom Reid

Thomas Reid was born in Glasgow on 14 March 1927; his father Thomas completed an engineering fitting apprenticeship with John Brown shipbuilders on the Clyde, and later worked as a maintenance engineer with a company involved in the textile industry. His mother Mary also worked in textiles but in a tailor’s shop. Thomas (junior’s) education was interrupted by WWII but he did well at high school, majoring in mathematics. On 28 March 1944, just two weeks after his 17th birthday, he volunteered for service in the Royal Navy. While joining as an Ordinary Seaman he was selected for the ‘Y Scheme’.

Dramatic wartime developments in radio and radar meant that some key combat roles were beyond the ability of ordinary conscripts. The ‘Y Scheme’ creamed off intellectually gifted youngsters straight from school. Candidates were subjected to a written test and an aptitude interview by senior officers. Once accepted, entrants received enhanced pay and promotion prospects, becoming Leading Hands within 12 months and Petty Officers a year later.

RAN Advanced Training

The need for advanced training in radio and radar technology was also being addressed in the RAN. In 1941 a new category of Wireless Mechanic (later known as Radio Mechanics) was introduced, and training took place at Melbourne Technical College. A further six-month intensive electrical engineering course for officers was introduced at the University of Sydney; afterwards candidates completed four-weeks officer training at HMAS Cerberus and 12 weeks practical training at HMAS Rushcutter. Graduates served as Radar Officers RANVR.

To overcome post-war shortages of suitable technical skills a similar initiative to the ‘Y Scheme’ was introduced into the RAN. New Recruit Radar Mechanics engaged to higher educational standards spent six-weeks initial training at Cerberus followed by six-months intensive electrical training at the South Australian School of Mines & Industries, and finally six-months practical training at HMAS Watson. These recruits received special conditions of service and accelerated promotion and were integrated into the Electrical Branch of the Royal Australian Navy.

Returning to Tom Reid

In Tom’s case he was immediately released from full-time service to complete the Senior Leaving Certificate. Once this had been completed it was off to HMS Royal Arthur, a former Butlin’s holiday camp at Skegness, on the coast of the chilly North Sea. Tom was mustered into the Radio Mechanics Branch to service new top secret radar systems. He was then seconded for 21 weeks to the General Post Office transmission station at Hillmorton in Warwickshire, the prime centre for communicating with RN submarines. He completed his training at the same time as Germany surrendered and hostilities in Europe ceased.

Next it was off to join the British Pacific Fleet, and just before Christmas 1945 he was billeted with about 3000 others at HMS Golden Hind, a massive tent city on the outskirts of western Sydney. With the war in the Pacific also over, in April 1946 Tom joined the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, travelling to England with a host of veterans and their Australian war brides. Tom left the ship in Colombo for HMS Simbang, the Singapore naval air station, where he remained for a year before returning home and discharge from the Royal Navy when he was still only 20 years old.

Tom returned to Glasgow and secured a job in a factory making light bulbs. In 1948 he enrolled in an electrical engineering course at the University of Glasgow with a small group of students; many like himself were mature aged from the armed forces. At this time Tom met Betty McKenna and shortly afterwards graduated with first-class honours in electrical engineering.

In 1952 Tom (senior) now 50 years old, with Mary, decided to migrate to Launceston where he secured employment as a maintenance engineer with the Tasmanian Government Railways. Coincidentally a group of Australian naval officers came to Scotland to recruit technical staff, and Tom was offered a five-year short service commission as an electrical engineer.

On 20 September 1952 Tom Reid married Betty McKenna and six days later Lieutenant Thomas Reid RAN departed for Australia in SS Orontes. A pregnant Betty remained behind. Tom made for Cerberus which then housed the Royal Australian Naval College. He joined a direct entry course from those with qualifications in engineering, medicine, dentistry and law. A fellow engineering graduate was Fred Lynham, later Rear Admiral and Chief of Naval Technical Services. Betty with her son, another Thomas, joined her family on 1 April 1953.

In June 1954 Tom was posted to HMAS Vengeance, a light aircraft carrier serving as the fleet training ship. Here he was one of a number of electrical lieutenants responsible for a part of the ship’s overall electrical system. His next posting was to HMAS Leeuwin in Fremantle as the Port Electrical Officer. Finally he was posted to the Tribal-class destroyer HMAS Warramunga, in charge of her 70-man electrical department. Warramunga was commanded by Commander Anthony Synnot, later Admiral Sir Anthony and Chief of Defence Force Staff. Although recommended for a permanent commission Tom sought new horizons, joining the Commonwealth Public Service as a Scientific Officer, with a posting to the small township of Woomera in desolate outback South Australia.

Woomera was a test range for British ballistic missiles as part of its program of nuclear deterrence. In 1957 this was formed into the Weapons Research Establishment (WRE). As officer-in-charge of telemetry this involved tracking missiles in flight to record how they performed. Among the staff that Tom recruited was Bill Boswell, who had worked in radar installation in RAN ships. Bill was later to be Director of WRE.

The two-stage Black Knight rocket was tested at Woomera. This was the precursor of the larger Blue Streak ballistic missile designed to deliver nuclear warheads over 2000 miles, placing Moscow within range of British weapon systems. With increased complexity British radar was replaced by American variants being used in space exploration. For Tom this involved commuting to the United Sates, a benefit he was to continue for the remainder of his working life.

In 1962 Tom took on a new position as senior lecturer in electrical engineering at the South Australian Institute of Technology, which incorporates many functions of the old School of Mines and Industries. The express purpose of the new institute, which had a close association with WRE, was to specialise in applied science and technology. While Tom was preparing for an academic career and studying for a PhD, he received an invitation to take over as the inaugural director of the Orroral Valley tracking station. He accepted in August 1964 and set about bringing the new station into life.

Tom and Betty also had to balance a busy home life as by this time they had four young children. Events took a dramatic turn in 1965 when Betty succumbed to a short illness, leaving a devastated family behind. Tom somehow balanced his career with bringing up the children. The next year Tom was introduced to a South Australian barrister, Margaret McLachlan, who had recently arrived in the capital. Margaret, who had never been married, took on the onerous task of looking after a new family when she and Tom married in 1966. Margaret was later elected as a member of the Australian Senate representing the ACT, and went on to become the first female president of the Senate.

Events leading to the Moon Landings

In an exercise on 27 January 1967, with the crew of Apollo 1 on board and within ten minutes of a simulated launch, there was a devastating fire with astronauts Gus Grissom, Edward White and Roger Chaffee incinerated on the launch pad. This resulted in the command module being redesigned and the next planned Apollo missions cancelled. In a search to avoid future accidents and achieve greater standards of excellence, discipline was taken to the highest level.

Rigorous protocols and surveillance were placed on stations with a massive build up in telex messages and paperwork. At Honeysuckle this was not Bryan Lowe’s strong suit and as paperwork began piling up on his desk so things began to slip. On 26 June 1967 a NASA Super Constellation arrived at Canberra with a team to conduct simulation exercises. It did not take long for the American visitors to find the locals were not up to speed and they demanded a replacement of the director and his management team. Tom Reid was seen as a clean pair of hands and was moved from Orroral Valley to take over the directorship at Honeysuckle Creek.

With ruthless efficiency Tom Reid swiftly ‘encouraged’ a number of resignations. Older engineers were replaced by younger technicians, some from the Navy, who although less academically qualified, had the drive, initiative and practical knowledge to work under extreme pressure in a difficult environment. These included men such as Kevin Gallegos, a former Petty Officer with a razor-sharp mind, who had honed his technical skills maintaining electrical equipment in RAN warships.

The station’s union representative, Bryan Sullivan, was a computer software specialist, a rare breed in those days. Bryan had also worked on warship electrical systems at Cockatoo Island Dockyard. Bryan wrote all the software for simulation training exercises.

When Tom’s deputy Mike Dinn travelled to Fremantle in July 1968 he came across the ex-NASA 5000-ton missile range instrumentation ship Coastal Sentry which had been sold for scrap. Mike uncovered a gold mine, acquiring complete operations consoles which were taken to Honeysuckle and used to fit out a simulation room. While not quite in keeping with NASA’s exacting standards the system worked and in a subsequent NASA inspection Honeysuckle went from the bottom to the top of the list of stations in efficiencies.

Readiness for Lunar landing

Apollo 9 blasted off on 3 March 1969 and now the stage was set for Apollo 10, the rehearsal of everything except the lunar landing. Apollo 10’s flight lasted from 18 to 26 May 1969 and during this phase Honeysuckle tracked the command module while Tidbinbilla looked after the lunar module. Its lunar module Snoopy separated from the command module Charlie Brown and descended to within 10 miles of the moon’s surface. The way was now clear for Apollo 11 to land astronauts on the Moon.

Coordinated by Tom Reid, Honeysuckle, Parkes and Tidbinbilla would be responsible for maintaining all communications with Apollo 11 during the crucial moon walk phase. These communications included televising Armstrong’s first step and monitoring his heart beat and respiratory rate, while at the same time enabling him to give mission control a second-by-second description of progress.

On the morning of 16 July 1969, in front of a crowd of over one million people crammed onto local beaches, camping areas and parking lots, Apollo 11 blasted off. When the spacecraft had travelled about 10,000 miles Goldstone, Madrid and Honeysuckle, one after the other, began their collective 24-hour tracking.

On Monday 21 July 1969 the Eagle lunar module separated from the Columbia command module. At 6.17 am AEST with Neil Armstrong and Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin aboard, Eagle landed in the Sea of Tranquility. Just after this important juncture, and to add to the pressure, at about 9 am AEST the Prime Minister John Gorton, with entourage, visited Honeysuckle. At 11.15 am AEST the moon rose into Honeysuckle’s view and the station promptly locked on to Eagle’s signals from the lunar module’s tiny 26-inch antenna. Downlink voice and telemetry signals streamed into the station, which after processing were sent to Houston.

It took the two astronauts over three hours to get ready for the spacewalk, linked by a series of hoses to the lunar module. It was 12.30 pm AEST with still no sign of the astronauts emerging. In another 35 minutes the moon would have risen sufficiently for the 210-foot dish at Parkes to pick up the download signals. Honeysuckle and Parkes were roughly on the same longitude, but Honeysuckle’s smaller dish could angle down to zero degrees to the horizon, whereas the larger dish at Parkes could only be angled to 30 degrees above the horizon.

As Armstrong exited the module at 12.56 pm over 600 million people from around the world were glued to TV screens. Neil Armstrong’s first step on the Moon with his famous That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind was recorded by Honeysuckle’s 85-foot dish, because it still had the moon well in view; video from the first moon walk came from Honeysuckle.

Tom Reid and his team had provided the first live television coverage of the moment when for the first time in history, a human being had set foot upon another celestial body. A truly great achievement and a wonder of the modern world.

Not to be outdone, the main signal from Parkes came online eight minutes and 51 seconds after the lunar module’s camera had begun recording and six minutes and 42 seconds after Armstrong had taken his first step. From then on until the end of the moon walk some 2½ hours later the signal from Parkes, stronger and of superior quality, was used for the worldwide TV broadcasts. But the only voice transmissions heard by the public on TV were those broadcast between Honeysuckle and Houston.

In Houston NASA introduced a six second delay before releasing TV pictures worldwide. This was to give enough time to cut should an accident occur. In Australia the broadcasts were live and as a result our local audience saw the pictures 6.3 seconds before the rest of the world.

The Aftermath

After the end of the Apollo missions the need for Honeysuckle declined and the future of space tracking centred on Tidbinbilla with the construction of a new 210-foot dish. With this change Tom Reid moved over to Tidbinbilla and Don Gray to Honeysuckle.

On 14 December 1972 Tidbinbilla had a view of Apollo 15 with the last man on the moon, Gene Cernan, with his crewman Jack Schmitt. On final departure Gene Cernan said: Okay Jack, now let’s get off – the last words spoken by a human on the moon and hardly living up to the standard set by Neil Armstrong.

In 1981 Honeysuckle was closed, with its 85-foot dish dismantled and transferred to Tidbinbilla, where it was rebuilt and put to work as a supporting antenna. In 1985 Orroral Valley was closed. Tom Reid stepped down as director of Tidbinbilla on 14 October 1988 and in 1989 he received NASA’s Exceptional Public Service Medal. He had also been recognised by the appointment as a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE).

The Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (DSCC) still remains at Tidbinbilla, now operated by CSIRO, as one of NASA’s network of major stations providing worldwide coverage. Its 90 staff support the 24-hour operations of the complex which has one 230-foot (70 m) and three 112-foot (34 m) radio dishes receiving data from, and transmitting commands to, unmanned spacecraft on deep space missions.

Summary

Just over fifty years ago in the ‘Greatest Event in our Time’ the United States of America was at the forefront of scientific discovery and space exploration, epitomised by successfully landing men on the moon and bringing them safely back to Earth. Australia, and elements from the Royal Australian Navy, made important and far-reaching contributions to these momentous achievements and thereby demonstrated a close cooperation with league leaders, a thirst for knowledge, and a capability for utilising high-level technology.

Some might argue this was the high point of our endeavours, and ask what has happened since, with seemingly declining educational standards and diminished technological abilities. More than ever leadership is sought to uplift from mediocracy and inspire another ‘Giant Leap for Mankind’, towards a brighter future.

Looking on the bright side, the recent November 2022 successful launch of the first of the Artemis series of rockets from the Kennedy Space Centre at Cape Canaveral makes us optimistic about once again returning to manned space flights. Twelve astronauts walked on the moon during the Apollo missions between 1969 to 1972; will they be joined by another man or woman after an absence of more than fifty years?

References

Goddard, D. E. & Milne, D. K. (Ed), Parkes: Thirty Years of Radio Astronomy, CSIRO, Melbourne, 2001.

Miller, Des, The Early Years of the Electrical Branch in the Royal Australian Navy, Naval Historical Review, Sydney, December 2014.

Sarkissian, John M., On Eagle’s Wings: The Parkes Observatory’s Support of the Apollo 11 Mission, Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, Vol 18, 2001, CSIRO, Sydney.

Tink, Andrew, Honeysuckle Creek, New South Publishing, University of New South Wales, 2018.