- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general, Naval technology, Naval history

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

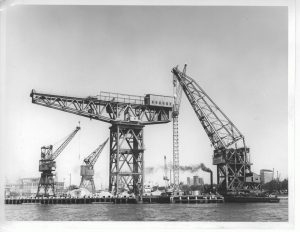

In the 42 years of this publication there has not been one article dedicated to Garden Island’s Hammerhead Crane. It is timely to correct this omission which has been done through researching our archives for information on this proud feature which has stood sentinel over the Island for nearly three score and ten years.

Why we have a Hammerhead Crane

With the advent of war Prime Minister Menzies told parliament on 1 May 1940: ‘A dry dock of a larger size than any in Australia has been an important strategic consideration since the size of capital ships has increased so greatly. I do not need to elaborate the great value to Australia of a dock capable of accommodating not only the largest warships but also merchant ships of great tonnage. The possession of such a dock would make Australia a fit base for a powerful fleet and would, in certain contingencies, enable naval operations to be conducted in Australian waters without the necessity for ships to travel 4,000 miles to Singapore for purposes of refit and repair. It is estimated that three years will be occupied in the construction of the dock.’ Not stated at the time was that the construction of the dry dock also required new workshops and modern machinery together with construction of a repair wharf with a large crane. Work on the dock commenced in December 1940.

On the 15th day of February 1942 Britain lost its great island fortress of Singapore to Japan. Of strategic importance to British and Dominion naval forces was the loss of docking and repair facilities for large warships. Without these it would be impossible to re-establish naval supremacy in the region. Accordingly a safer home was required to sustain a large fleet and that choice fell upon Sydney, giving impetus to the construction of the Captain Cook Dock and the associated hammerhead crane. Both of these large and impressive engineering statements were built to pre-war designs. While the essential features of the dry dock remain much as designed it has been adapted and continues as an essential part of naval infrastructure. The large crane on the other hand quickly became obsolete, as ship systems became smaller and of less weight the needs of craneage could be met by smaller and more versatile mobile platforms.

Construction and Use

The Captain Cook Dock was completed in time to assist the British Pacific Fleet with the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious being the first customer with an emergency docking required on 1 March 1945. Under normal circumstances the hammerhead crane might have been expected to have been built in Britain, where there were other examples of similar structures, and shipped to Australia for assembly. But with wartime exigencies a decision was made to build locally. Tenders were called in 1944 for the construction of a giant 250 ton crane which was awarded to the Sydney Steel Co Pty. Ltd. who were contracted to fabricate and erect the crane to the design of Sir William Arrol and with Sir Alexander Gibbs and Partners as consultants; with all mechanical and electrical equipment coming from England. Many delays were experienced and it was not until February 1952 that the crane was commissioned.

The hammerhead crane is an example of excellence in engineering design and manufacture of the mid 20th century. The crane epitomises the peak of naval construction of a battleship era which needed mammoth lifting structures to maintain their engineering machinery and main armament. With the eclipse of these types of ships when the last of the heavy cruisers HMAS Australia de-commissioned in August 1954 further naval use of the crane became problematic. However intermittent use continued from the mid 1950s to mid 1970s to discharge heavy machinery from ships to road transport bound for the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. While used infrequently the crane was important to support the aircraft carriers HMA Ships Vengeance, Sydney and Melbourne, the last of which remained in service until June 1982. Again in 1988 the crane was used to lift stators going to power generating plants and in the same year the famous 100 tonne steam locomotive Flying Scotsman was lifted ashore at the start of her Australian exhibition. Discounting test loads, the heaviest load the crane has been called upon to lift is said to be 227 tonnes but the heaviest we can authenticate is 205 tonnes of boiler machinery for the Liddell power station lifted in March 1968. The final lift appears to have been made in about 1992 after which the crane was de-commissioned, still in working order, with much of her machinery in its original condition.

When completed the crane was one of the largest such structures in the southern hemisphere and was one of about 60 of this type in the world. With many others being demolished there are now only ten remaining examples in existence and no others in the southern hemisphere. Five of those remaining are in Scotland, a reminder of the halcyon days of shipbuilding on the River Clyde. A similar crane at Singapore Dockyard was demolished with explosive charges in 1942 to prevent it falling into Japanese hands.

Technical Description

A comprehensive technical description of the hammerhead crane – ‘Erection of 250 ton crane on Captain Cook Graving Dock’ was prepared by Mr. Colin Stuart the Engineer in charge of its construction shortly after the crane was commissioned in February 1952. The following brief description is largely taken from this document.

The hammerhead crane consists of an asymmetric horizontal steel truss boom 83 m (275 ft) long, with a maximum radius of 40 m (131 ft), swivelling on a square section steel truss tower 15.2 m (50 ft) square, a height of 68 m (179 ft) from the wharf level to the top of the cantilever. The main machinery house is situated on top of the boom, making the total height of the complete structure 61.9 m (203 ft) from the wharf level. Foundations, which took three years to complete, consist of four main concrete bases 39.3 m (129 ft) deep and 30.5 m (100 ft) below the low water level being 4.6 m (15 ft) in diameter, taken down to rock bed. The maximum lift of the crane is 254 tonnes (250 tons) when the two main purchase hooks are coupled. All crane motors and swivelling gear are electronically driven. The two main purchase hooks are each powered by 90 horsepower motors (maximum 1,000 revolution to minimum 100 revolutions) with automatically adjusting brush gear for speed control. Combined, they provide a lift of 254 tonnes (250 tons) operated by one lever, a 40.6 tonne (40 ton) auxiliary hook powered by a 90 horsepower motor is also part of the lifting capacity of the crane. A 10.16 tonne (10 ton) capacity hook for handling lifting gear and other items is also available and there is also a 6.1 tonne (6 ton) travelling crane in the main machine house used for maintenance purposes. When tested initially after completion the maximum test load was 317.5 tonnes (312.5 tons) lifted, lowered and controlled. Structural steelwork used in the main sections totalled 1,422 tonnes (1,400 tons), machinery totalled 204 tonnes (200 tons) and electrical equipment totalled 71.12 tonnes (70 tons). The top of the tower is formed by four 20.32 tonnes (20 ton) main girders. Approximately 250,000 rivets were used in construction, with the last rivet driven by The Honourable Joe Cahill, Deputy Premier of New South Wales in February 1952 (he became Premier in April 1952). The lift operator accesses his control cabin via an external electrically controlled lift with capacity for six persons.

Redundancy

In its redundant state and lacking maintenance the crane is of no future use and consideration has been given to its removal. Accordingly on 21 January 2013 the following announcement was made: ‘Defence would conduct a period of public consultation for the proposed removal of the hammerhead crane located at Fleet Base East, Garden Island in Sydney, from Monday 21 January to Monday 18 February 2013. The proposal to remove the crane is being assessed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. While not heritage listed, the crane is known to have Commonwealth Heritage values and is located outside the Commonwealth Heritage Listed Garden Island precinct’.

The National Trust however has expressed strong opposition to the proposed demolition of the hammerhead crane which was listed on the National Trust Register in 1996, and in 2007 joined the National List of Heritage at Risk, being rated in the top 10 of that list. The Trust believes the crane should be retained and adapted as a tourist attraction as a similar crane has been retained in Scotland.

Garden Island contains some of the nation’s best preserved heritage and architectural features dating back to a few days after the arrival of the First Fleet to the present day. It may also be relevant that New South Wales has few enduring architectural and engineering features other than the iconic Harbour Bridge and Opera House. Other major structures serving as testament to man’s creative ability are the Captain Cook Dock which by extension includes the hammerhead crane and the Snowy Mountains Scheme, all with associations with the hammerhead crane.

Options

Those charged with the efficient operational use of assets under their control are often faced with difficult options. A major concern is obviously one of cost efficiency.

Could the structure be adapted for future use: this is a moot point and suggestions which have come forward for an inverted boat shaped restaurant appear fanciful and lacking in understanding of engineering difficulties as well as largely destroying the visual integrity of the structure.

Possibly most telling is that in its present location the crane compromises the full use of available wharf space needed in support of future generation naval ships.

All these issues should be fully addressed in the forthcoming Defence sponsored environmental report.

Final Analysis

The hammerhead crane remains one of the most enduring features of the Sydney skyline known to most residents of our premier city, countless visitors and generations of servicemen and women. Should it just be dismissed as another casualty of obsolesce or is it an essential feature of our rapidly disappearing maritime heritage needing preservation?