- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval Intelligence, WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Earlier this year your Editor had the pleasure of meeting James (Jim) Burrowes, aged 94, and Beryl, his ex-WAAF wife of 66 years, aged 93. They were married in 1950. The following extract is taken from an interview with Jim after browsing his extensive website and is produced with his approval.

Signals School

On leaving school in Melbourne in 1940 Jim worked as a clerk in a chartered accountants office. Along with most other young men entering the services, in January 1942 when he was 18 and no longer needing parental consent, Jim took himself off to Albert Park Barracks and along with about 50 others joined the AIF. Here a decision was quickly made that would forever change his life. The Recruiting Sergeant called for volunteers from those who had office work experience. Jim and half and dozen others raised their hands and they were destined to become Signallers, with the remainder joining the Infantry.

‘We were encamped at Camp Pell in Melbourne’s Royal Park and for six weeks were marched daily to the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) and taught how to send and receive Morse code. Here we achieved a speed and proficiency of 25 words per minute.

‘The first real job was a posting to Land Headquarters (LHQ) then at the outer Melbourne suburb of Park Orchards. Here we maintained radio links with Port Moresby with the messages passed to and from Military Intelligence at Victoria Barracks.

‘With MacArthur’s push north we were relocated to Indooroopilly on the Brisbane River. A prized billet, as the Australian Women’s Army Service, which was taking over some duties and thereby allowing more male troops into combat roles, was also based here. From our new barracks we were trucked daily to the basement of the yet-to-be-built St Lucia campus of the University of Queensland. We were again maintaining Morse links with New Guinea.

Nine months after arriving in Brisbane there was another call for volunteer signallers for a special operations assignment working with the United States Amphibious Forces which was part of the US 7th Fleet. Not learning too well from previous experiences of never volunteering, Jim with five others put their hands up. Another reason was that Jim’s elder brother was a Japanese POW at Rabaul in New Britain and his twin brother was also serving in New Guinea.

Life with Uncle Sam

On 13 July 1943 the new volunteers found themselves at Brown’s Bay, a jungle training facility just north of Cairns. Here they met six other Australians who were expatriate New Guinea planters or administrative officers who had been seconded from the Allied Intelligence Bureau’s M Special Unit (Coastwatchers). They were destined to become leaders of parties infiltrated into enemy territory where they were to reconnoitre the Japanese status prior to the invasion by the US forces. The Signallers were assigned one each to the leading Coastwatchers, with Jim being attached to Andy Kirkwall-Smith.

In August 1943, at Cairns, they embarked in a USN Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) to establish a base on Fergusson Island, northwest of Milne Bay and near the larger Goodenough Island. Jim’s twin brother Tom, serving with the RAAF, was based at Goodenough but they were not to meet.

Travelling by USN Patrol Boat at high speed, with torpedos stacked on deck ready for immediate use, the Kirkwall-Smith party made a sortie into enemy occupied Gasmata in New Britain. Landings were also made on Kiriwina in the Trobriand Islands and Woodlark Island with no sign of enemy occupation. Suddenly, without any prior notice, the Amphibious Force Unit was disbanded with no reason given. The party leaders returned to the Australian Coastwatcher organisation, with Jim and two others volunteering to remain with the Coastwatchers and the other three Signallers returning to their mainland parent LHQ unit.

Coastwatching

It was back to basics at the Coastwatcher training camp at Tabragalba, a farm requisitioned for that purpose, near Beaudesert and close by the Jungle Warfare School at Canungra.

‘At Tabragalba we were toughened up to a peak in physical fitness and learned commando skills such as unarmed combat, and our Morse code training was also brought up to speed. We had plenty of time at the beach, the then not so well known Surfers Paradise, where we practiced surf landings from small rubberised inflatable boats.

Later in March 1944 a party was required to infiltrate into Hollandia (now Jayapura) to assess the Japanese presence prior to a planned US invasion. Jim was selected as the Signaller amongst a 12 strong party, which included six local natives. However, at the lastminute Jim was replaced by another Signaller, Jack Bunning. On 22 March the party led by Captain ‘Blue’ Harris was taken inshore by submarine but only 11 were off-loaded into two boats. Nothing went to plan with the inflatable boats being swamped in the surf and losing much of their equipment, including the radio, and soon after landing they were ambushed. Five, including ‘Blue’ Harris and Signaller Jack Bunning (who had replaced Jim), were killed. Those who escaped went bush and it was many months before they reached friendly territory. Jim’s philosophy was ‘Life’s all about luck – good or bad!’

‘My next assignment was to the Coastwatcher base at Nadzab, which was part of a USAAF air-base in the Markham Valley, inland from Lae. We arrived there by those reliable work-horses of the South Pacific, the C47s (later DC3s). Here I was hauled over the coals for having possession of a Colt 45 and a semi-automatic US carbine, from my American amphibious landing force days, but I was allowed to keep the weapons. After a few months I rejoined the Kirkwall-Smith party, this time using a small island off Madang as a base. We were in luxury, being provided with good food from the supply ship, an ex-Chinese river steamer, HMAS Ping Wo.Our good fortune also attracted a lot of rats, and calling for improvisation we rigged up a kerosene tin just below the floor, which was filled with water and had a jam-tin on a central wire shaft with a small amount of cheese attached. When the rats leaned out for the bait, the jam-tin would spin and the rats fell into the trap.

‘Our main task was to maintain radio contact with other coastwatching parties in the hinterland behind Wewak, Aitape and Hollandia and then pass these messages on to our main base at Port Moresby. At this stage I was using the popular AWA 3B Teleradio requiring wet batteries and therefore a generator set comprising a Briggs & Stratton engine to recharge them. Battery charging was not a pleasant evolution as the old engine was inevitably cantankerous to start.’

The Coastwatchers’ AWA 3B Teleradio was of rugged design able to withstand heat and wet conditions as well as amateur handling. It had a range of 400 miles on voice and 600 miles by Morse key. Its great disadvantage was weight and bulk, needing at least 12 carriers for transportation. Broken into components it was carried in three heavy boxes, usually slung on poles so that each box was shared by two men; in addition petrol had to be carried. Units were frequently carried for more than 100 miles but given the difficult terrain, lack of roads and humidity, porterage over one day rarely exceeded ten miles.

After a few more months it was back to Lae, this time by Beaufort bomber, the same type of plane that his twin brother went down in on a raid over Rabaul. From Lae, Jim was flown in a grand US Mariner flying boat, to Jacquinot Bay in New Britain. Here he joined with a party led by the veteran coastwatcher Basil (Fax) Fairfax-Ross who had been preparing for an advance landing of Australian troops.

A Long Watch

‘After a lengthy trek through the jungle from the south coast of New Britain with a team of native carriers we duly arrived in November 1944 at a base camp in the Baining Mountains of the Gazelle Peninsula overlooking Rabaul. The party now comprised Captain Malcolm English, Lieutenant Joe Willis and Jim (now a Sergeant) and ten Allied Intelligence Bureau trained Papuan troops. Our purpose there was to report Japanese movements whether by land, sea or air.

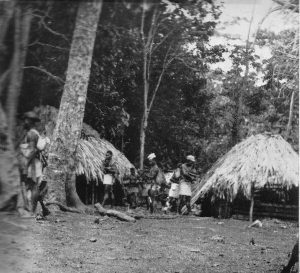

Our camp was set up on a mountain ridge to avoid any unpleasant surprise by the enemy. At each end of the camp two or three of our faithful troops were on sentry duty. We had thatched huts which provided some shelter to body and equipment but we slept in our clothes, with weapons loaded and ready.

The daily routine was waking at dawn for ablutions, after this the first of our two meals for the day was breakfast. It usually consisted of rice and some canned vegetables. We had tea but there was no milk. We next had an overnight report from the Papuans on the security situation and discussed the day’s program. As we were on a ridge with no fresh water part of the daily routine for our Papuans was to harvest rain-water to maintain our supplies. Daily patrols would be made to various sectors but most importantly checking the airstrip at Rabaul to monitor aircraft movements. There were two daily radio schedules (sched) with Port Moresby and other Coastwatching parties. Once when the radio had no signal, I was horrified to be faced with a mass of wires, valves and parts and to realise that whilst we had plenty of operational training we had no teaching into the technical function of the sets. Fortunately with a few spare parts of resistors and condensers the set sprung back into life.

Our supplies were flown in by Catalina or Liberators that were dropped in a ‘storpedo’, an improvised storage container that was parachuted into a nominated drop zone. The parachutes were covered in hessian for camouflage. The majority of our drops were food and of this 90% was rice, mainly for our native troops. Despite having 100,000 Japanese below us at Rabaul it was minor miracle that they never observed one of these drops or that they never used radio directional monitoring which would have helped locate our static position. After completing the last radio ‘sched’ of the day we retired for our evening meal – anyone for more rice!

The War is Over

On 15 August 1945, after ten months on our perch above Rabaul the war was over. Jim sought permission to move down to Rabaul in the hope of finding either of his brothers, believed to be prisoners there. However permission was denied as it was uncertain as to how the Japanese might react to informal troop contact. Unfortunately by this time Jim’s brothers were already dead.

The Baining Mountain campsite was abandoned and the party trekked down to join fellow Coastwatchers at a base camp near the infamous Tol Plantation, where about 160 Australian troops who had evacuated prior to the fall of Rabaul were captured and executed. From there they weretaken by ship to the camp at Lae which was then closed. The remaining five of us sailed around the Huon Gulf to Finschhafen where we joined thousands of troops living in tents near the airstrip where we expected to remain for several weeks if not months.

Suddenly one morning a Liberator touched-down. A call was made for the five Coastwatchers and we were flown directly back to Brisbane; Jim having lost two brothers in the war was quickly given a compassionate discharge. He returned to a successful career in chartered accountancy, living in Melbourne. In 1990 Jim was awarded the Order of Australia Medal for his service to the Royal Life Saving Society.

On Anzac Day Jim usually catches up with a fellow ancient Coastwatcher, ex RAN Coder Ron (Dixie) Lee. Over 400 men served with Australian coast watching units during WWII but sadly now are nearly all gone and we believe Jim Burrowes and Ron Lee to be the last men standing. A final word from Jim, who says that although he was Army as a Coastwatcher he was also proud to be part of a naval organisation. A future article on Ron Lees is intended.

Further information on Jim Burrowes

Ex-Sergeant James Burrowes is now possibly one of the last surviving Australian Coastwatchers. Further information is available on his website ‘How the Coastwatchers Turned the Tide of the Pacific War’ https://tinyurl.com/coastwatchers-war. His email address is<jim@starbiz.com.au>