- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - Between the wars

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Penguin (Shore Base II – Balmoral)

- Publication

- December 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Robert Stephenson

Part I of this series appeared in the September 2023 edition of this magazine. Since that issue the following information has come to light. With the outbreak of the Korean War there were insufficient fighting forces to meet the expected demand, resulting in the introduction of National Service in 1951. For the early Naval intakes HMAS Penguin once more became a major barracks and movement centre and further training facilities were added to cope with National Service training. During the period 1951 to 1954 Penguin housed the Navy’s National Service Recruit School. The following ships were used in training National Servicemen.

HMAS Condamine was at Broken Bay in November 1953 with Class 14 of RANR trainees doing 13 days continuous on-board training. Later that month these were exchanged with Class 15. On 22 November 1953 she transferred 37 National Servicemen plus two Instructors to HMAS Australia. Also filling in the role of training ships were the corvettes HMAS Junee from February 1953 until she paid off in August 1957 and her sister ship HMAS Murchison from November 1954 until she too paid off in January 1956.

When serving as training ship between 1953 and 1954, the famous cruiser HMAS Australia made a number of calls to Westernport from February 1953 where she would take from 150 to 200 National Service trainees on short cruises around the Australian coast and as far as New Zealand. It is assumed that National Servicemen were aboard during the Royal visit by HM the Queen and Prince Phillip in the Royal Yacht Gothic from February 1954 when Australia accompanied Gothic for six weeks while on the Australian Station. Australia paid off on 31 August 1954.

The aircraft carrier HMAS Vengeance assumed the role of training ship in July 1954 and continued taking National Service trainees on short cruises. The program was altered when she sailed for Japan on 27 October 1954 with the ship absent for six weeks with 281 National Service trainees aboard. Vengeance ceased training duties in April 1955 and later returned to England, reverting to RN service.

HMAS Sydney, another aircraft carrier, was redesignated as fleet training ship in April 1955 and began her role hosting various drafts of National Servicemen until the scheme ended in 1957. Later during the Viet Nam War between 1965 and 1972 she made many voyages carrying Army and Air Force National Servicemen to Viet Nam, being affectionately known as the Vung Tau Ferry.

Burke II – The Last Intake

The last intake of Burke II recruits reported for duty on 07 January 1957 at HMAS Lonsdale, Port Melbourne then marched to the Port Melbourne railway station to embark on a train for relocation to the training base HMAS Cerberus. After disembarking at a siding inside the base we were quickly formed up by petty officers under a large covered parade area for an address by the Cerberus Commanding Officer and Commodore Superintendent of Training, Commodore John Plunkett-Cole RAN, and the National Service Training Officer, Lieutenant Alan Beaumont RAN.

On arrival we were subjected to the usual taunts by the regular sailors such as: ‘you’ll be sorry’ and ‘your mothers can’t help you now’ and so on but at a later stage we managed to adequately extract revenge on most of these perpetrators. We swore the oath of allegiance to Queen and Country and from that point were officially enlisted to become new recruits in‘Pussers’, the Royal Australian Navy Reserve RANR (NS). From a roll call small groups (‘Classes’ of about 12/15 recruits) were formed. My group was allocated to Class SN1 and introduced to training Petty Officer Percy Perfect, who took charge for the duration of our training.

PO Perfect was ex-Royal Navy and a rugged, no-nonsense, disciplinarian specialising in seamanship and gunnery. Being one of the old school with many years’ service including service at sea during WWII, his challenge was to knock Class SN1 into shape so that at the conclusion of our training we became competent Ordinary Seaman trained and rated Seamen Gunners Quarters SG(Q).

The Burke II intake’s recruits were not only training to become Seaman Gunners SG(Q), many others, especially those with trade skills, were trained in separate classes for other branches of the service, i.e. mechanical engineers were known as stokers (MIE), electricians, electricians mates (ElM), radio engineers, signals (Sig), and cooks (C). Some clerks were writers (W) and/or supply ratings (S), others were trained as officers’ stewards (O/S), and so on.

Petty Officer Perfect commenced by outlining the rest of the day’s activities and the basic rules of the base, and nominated Greg Keays as our class leader to which we all agreed. Rules included: classes moving around the base must form up and march at the double (jog) and caps were to be worn at all times when outdoors. He also taught us the Navy’s traditional terminology and unique slang, and became our surrogate father, mother and confessor as well as our teacher but at the same time was always very strict but fair. Any class member who didn’t conform to the Navy’s hair code was ordered to the base barber for the obligatory short back and sides. We learned the Navy salute and were told to salute officers when moving around the base as individuals or give an eyes right or left on the command of the class leader when marching at the double in smaller groups.

After a cafeteria style meal (scran) in the dining area (mess) we doubled to the stores and were issued with our Navy uniforms and cap and various items of clothing (‘slops’ – a seaman’s jumper, shoes and socks, and a heavy canvas sea bag with a long-shanked security padlock for stowage of clothes and kit, plus hammocks for sleeping. We then doubled to our allocated Living and Recreation Huts (mess) for instructions on how to assemble, rig and stow the hammocks. It was here we met and got to know our fellow class mates who were from South Australia and Tasmania with the majority from Victoria. We came from some very diverse backgrounds and civilian occupations but had a keen interest in all things Navy and became great shipmates.

Class SN 1: Names, Nicknames, States

William Aitken (Tubby) South Australia, James Baker (Doughy) South Australia, John Barnes (Skeeta) South Australia, Russell Belyea Victoria, David Brown Tasmania, James Goudie Victoria, Gregory Keays Victoria, Steven Ludham Tasmania, Barrie Pearson (Pancho) Victoria, Robert Stephenson (Slippy) Victoria, Clifton Swift Victoria, Gayne Watson (Barney) Tasmania.

Nicknames are traditional in the Navy and derive from the RAN’s close links with the Royal Navy. Certain names such as Baker automatically attract the tag ‘Doughy Baker’, Clarke becomes ‘Nobby Clarke’ and Miller becomes ‘Dusty Miller’ and so on. However, others already had nicknames that were given to them by friends and/or family and these continued.

Initially, for many of us, getting the hang of slinging a hammock was quite challenging as was being able to swing up on to it and settle down and not roll over and fall off, landing on the unforgiving deck some three to four feet below; however after a number of falls and a few bruises, it became second nature and later it was difficult to go back to sleeping in a bed. Every morning the hammocks were neatly lashed up, resembling a cocoon, and stowed in a wire bin in a corner and the mess then become our recreation room.

We learned to stow our kit and iron our uniforms and tie the ‘tally band’ around our caps secured with a neat bow and the satin dress collar (silk) around the neck. The tally band signified we were National Servicemen with the gold letters RANR (NS). The bell bottom trousers of our blue number one uniform (square rig) were ironed with seven horizontal creases (representing the seven seas) in each leg and the ‘T’ shirts (whitefront or flannel) and jackets were ironed inside out with creases inwards. We quickly learned that creases stayed in place when clothes were carefully folded and placed under the thin ‘paillasse type’ mattress in the hammock pressed by our body heat.

Washing clothes (dhobying) was done in a bucket and hammocks were washed and scrubbed every week. This was done on Sunday afternoons – ‘make and mend day’ after church parade.

The first few weeks involved an intense training regime from sunup to sundown, learning the way things were done in the Navy and the Navy’s special terminology, and the various bugle calls and piped signals that signified reveille, lights out, etc. This involved a lot of exercise, especially moving everywhere at the double, with little or no spare time. We had to learn (for some of us the hard way) that the Navy way was to respond immediately to orders and signals and jump out of our hammocks at reveille, stow the hammock and get to the toilets (heads) and showers before all the hot water was used up, shave, get dressed in our daily work clothes, then move on to the dining mess for breakfast.

However, some slow learners were placed on charges by petty officers to go before the Training Officer for disciplinary action. Discipline usually involved a kit muster in our precious spare time and we soon learned to conform to the Navy way. Keeping the mess clean and tidy was paramount as was hygiene and everyone’s responsibility; random inspections were performed by officers wearing white gloves. A petty officer would enter the mess and call us to attention with ‘Hoi’ and the officer would then carry out the inspection by moving his white gloved hand across various surfaces. If the glove became soiled the whole class would be placed on a charge. The penalties could either be a kit muster for all or additional time marching at the double around the parade ground.

At times, without warning, we were woken in the middle of the night and told to get dressed and be formed up outside the mess in three minutes and taken on a lengthy march at the double up the road leading to the west gate exit from the Base. This was, undoubtedly, to keep us alert and improve our physical fitness. It became second nature to expect this to happen at any time so we were in our hammocks partly dressed and always ready.

Having enlisted for overseas service we received a number of disease prevention immunisations, including cholera, smallpox, tetanus, typhoid and yellow fever injections, suffering the after effects including sore arms for days after and weeping pustules on the upper arm from the smallpox vaccination. Despite the discomfort of the intense training regime it continued with no leave or visitors allowed for the first few weeks after which visitors were welcome on Sundays after church parade.

Generally, the meals (scran) we received were good and there was always plenty but the powdered eggs were a big no-no! The Navy’s slang for food includes ‘RAN Steak’ (lambs fry and bacon), ‘Pope Steak’ (fish on Friday) and ‘Duff’(pudding or sweet). However, there was always the base canteen ‘Millionaires Club’ where an alternative meal could be bought.

Communicating with the outside world was a big problem with long queues at the pay phones which were only accessible in our spare time, or by writing letters. Receiving mail was always a treat and many couldn’t wait to receive news from home or love letters from their girlfriends.

Nasho Ceremonial Guard

We had plenty of marching practice on the base’s large parade ground. Having experience with the Army Cadets at high school, along with a number of others I was selected as a member of the Nasho Ceremonial Guard and daily flag (White Ensign) raising party. This involved dressing in the uniform of the day plus white belt with bayonet scabbard and gaiters and being issued with a rifle and bayonet from the armoury to provide the guard at the morning White Ensign raising ceremonies and other important events.

The Royal Navy’s White Ensign was adopted by Australia from the RAN’s inception and can only legally be flown by the Navy’s commissioned ships. Most naval bases fly the White Ensign as they are commissioned also. On 01 March 1967 the RAN adopted a new Australian White Ensign dispensing with the Royal Navy’s red cross of St George. This came about due to the RAN’s integration with the United States, replacing it with the Southern Cross and Federation Star in blue on the white background but retaining the Union Jack. The lack of British involvement in the Vietnam conflict added impetus to the need to ensure the RAN was distinctly identifiable as Australian.

We were all delegated to various watches, tasks, commonly referred to as ‘tricks’, such as security, i.e. checking the doors and locks on the many warehouses and buildings around the base during the night and key punching Bundy clocks at various points, logging the time of inspection. The training regime included lectures by specialist Navy personnel and instructors where we learned the theory and were given hands-on practical demonstrations of seamanship and gunnery plus safety instructions before our time at sea arrived.

Gunnery Training

We experienced live firing of a number of different weapons at the firing range including rifles and automatic small arms, i.e. Owen and Bren guns. We endured a demonstration of the effects of tear gas in an enclosed area causing nausea and eye irritation and loss of vision which resulted in a mass exodus until the gas cleared. We also witnessed the awesome rapid fire power of anti-aircraft Bofors and their incredible noise and shock waves.

At the West Head firing range we donned flash protection clothing and, in one session along with other classes, fired off 90 rounds of 4.5 inch (115 mm) shells receiving hands on experience at each of the various tasks involved in preparing and firing these big guns, i.e. range finding, elevation, sight laying, etc. Loading the gun involved handling the heavy 4.5 inch shells very carefully across both arms, then locating and pushing them home into the breech with the closed fist protected using a canvas fist pad, then closing the breech, firing on the command of the Gunnery Officer ‘Guns’ beingsure to stand clear of the white hot shell casings as they were ejected from the breech. Any exposed facial or body hair was lost from the flash and heat generated from the breech.

We also suffered temporary hearing loss from the incredible noise and bone jarring shock waves. We weren’t issued with hearing protection. The smell of cordite and smoke emitted from barrel and the breech lingered on our clothing for the rest of the day.

Despite our best efforts we didn’t manage to hit the target, nevertheless it was a fantastic experience especially listening to the shells rocketing through the sound barrier as they sped on their way to the target, a large mooring buoy located a few nautical miles out to sea.

Physical Training

Physical training classes conducted by the PT Instructors (PTIs) were held on a regular daily basis. These vigorous workouts were designed to improve our physical fitness and no one could be exempted.

There were also two swimming pools at the base, one indoor pool and another open air pool which was shark proofed and fenced off in the water near the wharf on the foreshore of Hann’s Inlet. Those who were poor swimmers were given swimming lessons and instruction in their own time by the PTIs to bring them up to the required standard.

As a survival exercise we were instructed to jump into the indoor pool fully clothed with our shoes and socks on and whilst treading water remove our shoes, socks and trousers, and tie the bottom of the legs of the trousers tightly and holding the waist band throw them in the air to fill with air on the way down thus forming a crude buoyancy aid. The outdoor pool was used at a later stage when we had sporting events.

Weekend Leave (Liberty)

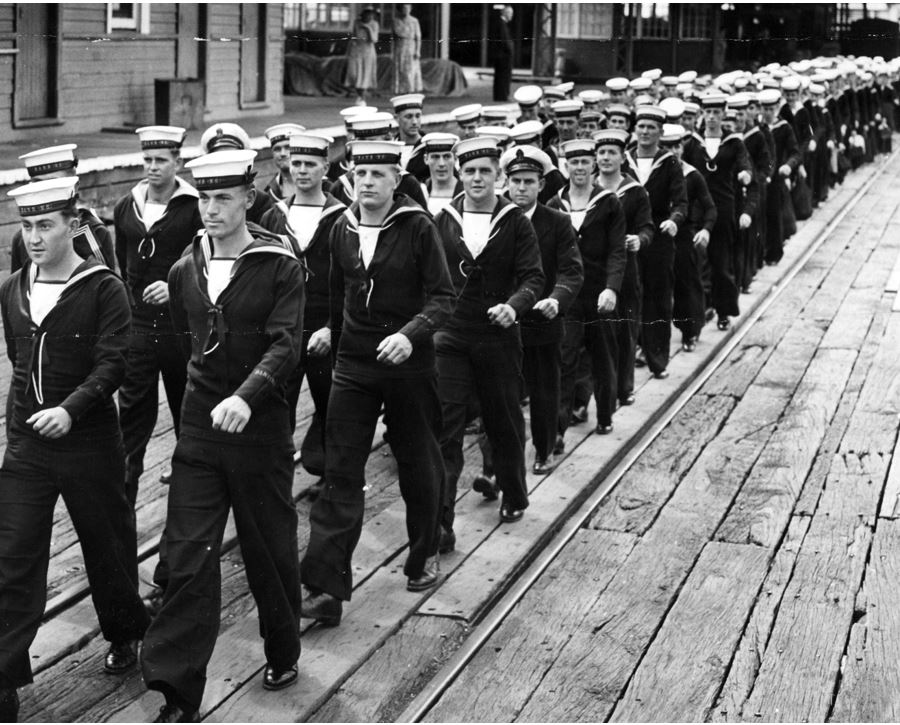

After about six weeks our first weekend leave (liberty) arrived at last and we paraded in full uniform, blue number one (square rig) under the covered parade area adjacent to the siding where we first arrived. Before boarding the train, we were addressed by the training officer on our expected behaviour whilst at liberty and carefully inspected.

Those that passed muster were soon on the train which stopped only at Caulfield Station and Flinders Street Station in the heart of Melbourne, arriving at approximately 1730.

Although Nashos were forbidden to drink at the Cerberus wet canteen the famous Young and Jackson’s pub was directly opposite Flinders Street Station and civilians aged 18 were legally allowed to drink, so some of us made a dash to the pub to order drinks before it closed at 1800.

Young and Jackson’s is also the home of the famous painting of Chloe, the priceless 1875 life-size nude painting of a beautiful young lady by French artist, Jules Joseph Lefebvre. Chloe has been very popular with servicemen for decades especially during the First and Second World Wars and the painting, which is held under tight security, can still be viewed in the hotel’s main dining room on the first floor.

Our Burke II group of fit young Nasho recruits, who had been without female company for some weeks, at a time of extremely conservative attitudes to nudity and sex, found it quite fascinating.

HMAS Sydney III

After the initial recruit training at Cerberus we were ordered to pack up our kit and hammocks and parade outside the mess dressed in our blue number one uniform then marched, sea bags over the right shoulder and hammocks under the left arm, in our class groups to the siding to embark the train bound for Williamstown to join the ship’s company of HMAS Sydney III for our sea-going training.

Thus ends Part II of our Nasho Odyssey.