- Author

- Head, M.A., S.J.

- Subjects

- History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1989 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

There is no more frightening end to a warship than the sudden death of the internal explosion. One moment a ship can be lying quietly in harbour and the next, torn apart by a devastating explosion. The suddenness of the end usually gave the crew very little chance of escape.

In the first years of the century internal explosions in magazines, which usually were violent enough to destroy a ship, were quite common. The reason generally given was instability of the cordite, a gelatinsed nitro-cellulose, which had been introduced as the main propellant in the Royal Navy in the 1890s and passed from there to general use. An improved type, Cordite MD, had been introduced in 1901, but experts still realized that if manufactured with impure materials it could have a nasty habit of exploding spontaneously. The French had lost the old Irena in a Toulon dock when she suddenly blew up on 12 March 1907. They later lost the new battleship Liberté in September 1912.

During the First World War the pressures and demands for greater production could well have resulted in less than perfect quality in the manufacture. Whatever the reasons, the Russians lost the dreadnought Imperatritsa Maria when she suddenly blew up at Sevastopol on 20 September, 1916. The Japanese lost their first dreadnought, Kawachi, when she erupted in a ball of flame in Tokuyuma Bay on July 12, 1918. The Kawachi followed in the tracks of the small battlecruiser Tsukuba which had been lost in Yokosuka on January 14 the previous year.

In Italy the pre-dreadnought Benedetto Brin blew up at Brindisi on 27 September, 1915, followed by the new dreadnought Leonardo de Vinci in Taranto on 2 August, 1916. The Italians believed that both of these ships were blown up by Austrian saboteurs, and that remains a strong possibility.

Speculation and investigation continued into the instability of the cordite. Eventually it was to be discovered that a small quantity of iron pyrites in the atmosphere could cause serious chemical breakdown. Another source of difficulty was the solvent used to bond the cordite, usually a type of petroleum jelly. This had the nasty habit of going up in a flash if exposed to fire or explosion. The Germans introduced a new mixture known as Centralite into their RPC/12 propellants which made a stable mixture which would certainly burn, but would never flash.

It is sometimes believed that German magazine security was much better than anyone else, and therefore contributed to the fact that they lost no ships to magazine explosions, either in action or spontaneously. This is actually not true and their precautions were inferior to those of many other nations. However, the British cordite was stored in silk bags with an igniter of black powder at each end. It was so fine that it tended to seep through the silk. If the charges were stored end to end, then the flash could very easily pass down the line from one to the other. The German advantage lay in the superior quality of their propellant and the fact that it was stored in heavy brass cases, which meant that the black powder igniters were much less exposed. The British, however, did notably tighten their quality control in the making of MC cordite after mid 1917, and over 6,000 tons of defective cordite was withdrawn.

The British, however, did lose three major ships to internal explosions, the pre-dreadnought Bulwark in 1914, the armoured cruiser Natal in 1915, and the dreadnought Vanguard in 1917. I believe it was said by James Bond, ‘Once is an accident, twice is coincidence, and three times is enemy action.’

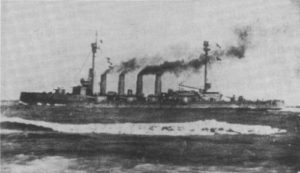

The armoured cruiser Natal had joined the fleet in 1907, one of four new Warrior class ships with a displacement of about 13,550 tons and mounting six 9.2″ and four 7.5″ guns. The maximum armour thickness was about 6 inches and they had a speed of 23 knots. The Warriors were considered good ships for their time, but their time was brief, the first of the battlecruisers were already nearing completion.

During 1915 the Natal spent most of its time with the Grand Fleet in the 2nd Cruiser Squadron with the sister ships Cochrane and Achilles, and the slightly larger Minotaur and Shannon. The squadron alternated between patrols and lying in a base, usually Scapa Flow. However, Jellicoe had already started to rotate his ships through Cromarty on the Moray Firth to provide at least some recreational facilities for the crews, as there was little for them on the bald rocks of the Orkneys.