- Author

- Head, M.A., S.J.

- Subjects

- History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1989 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This routine was broken only by trips to southern dockyards for refits. During the summer of 1915, the units of the 2nd cruiser squadron went south, one by one, to Birkenhead to be refitted and to give the crews extended shore leave. Natal arrived on November 22nd and went straight into dock. Two weeks later she sailed again to Scapa Flow, and from there to Cromarty Firth which she reached on 17 December. During her refit the magazines had been emptied and a new and checked supply of ammunition brought aboard. She had sailed Birkenhead with a number of her crew missing, and three civilian fitters who were still doing finishing work on the ship.

The ship had gunnery practice on the 20th and then settled down to enjoy the Christmas break in port. On the afternoon of December 30 a football match had been organised and a total of 93 ratings went ashore in an auxiliary drifter. The Captain, Eric Back, ran a luncheon in the wardroom to which three wives of the officers, a Mr and Mrs Dodd and their three children and eventually three nurses from the hospital ship, Drina, were invited.

Just after 3.20 p.m. a huge explosion shook the after-section of the ship. Several of the crew, fortunate enough to be on deck, were blown into the water. There was no time to close any watertight doors and about three minutes after the explosion the ship started to list heavily to port. At 3.30 p.m. she capsized and sank.

More than 350 officers and men went down with the ship, together with all the guests at the luncheon party, and two of the three civilian fitters.

Investigations followed rapidly. Jellicoe knew the defences were good, but even so a German minelayer had penetrated the patrols and laid a field just off the entrance early in March. Was it possible that a U-boat had penetrated the harbor? Lt. Fildes, the surviving officer of the watch, was certain it was an internal explosion. This was confirmed a few days later when divers reported that the explosion was internal and had blown out on both sides of the ship. The Admiralty duly reported that Natal ‘…blew up and sank yesterday afternoon while in harbour.’ The court martial which followed acquitted all the survivors but still was unable to come up with any solution. Cordite instability was finally blamed. But was it the cause?

There already had been the Austrian experience. More effective and just as romantic were the German operations in the United States. Here a number of German saboteurs, possibly under the direction of the military attaché, the famous Franz von Papen, set up a factory in the engine room of the interned German liner Friedrich der Grosse and produced over 400 fire bombs. Men like D. Walter Scheele, Paul Koenig, Franz von Rintelen, and Wolf von Igel became associated with this operation. At one stage they planned to blow up the huge construction dockyard at Hog Island, an attack foiled only at the last minute.

One of the weapons produced was known as the ‘cigar’. It was a small cigar-shaped cylinder with a copper plate in the middle and sealed at each end, usually with lead. One half of the cylinder was filled with sulphuric acid and the other with chlorate of potash or picric acid. When the acid burnt through the copper it produced a jet of flame of great heat which could burn for up to two minutes. The thickness of the copper plate dictated how long it would be before the explosion.

The German agents found plenty of willing assistants amongst the Irish dockworkers in the USA, many of whom would have been members of Sinn Fein or at least in sympathy with them. It is estimated they managed to destroy around forty British or French ships which operated from US ports. The Irish would also have had friends or relatives amongst the Irish dock workers in British ports such as Birkenhead, and a little ‘technology transfer’ is not out of the question.

The court of inquiry found defective cordite, but was it just an inconvenient explanation. Some of the survivors believed that sabotage was involved, but no one could prove it. It was unlikely that if someone had planned the bomb, they would have remained on board for it to go off. There was no reason to doubt the crew’s loyalty, and there was no guarantee that any of them would be able to get ashore at precisely the time they would wish if they had set a bomb there. Two of three fitters went down with the ship.

But there is one person of interest. The fitter, an ordnance worker, had left the ship just before Christmas. When the Vanguard blew up in 1917 it killed all but two of the crew. Two fitters who had been working in the ship for several days had left the ship a few hours before. One of them was the fitter who missed being blown up in the Natal. Coincidence?

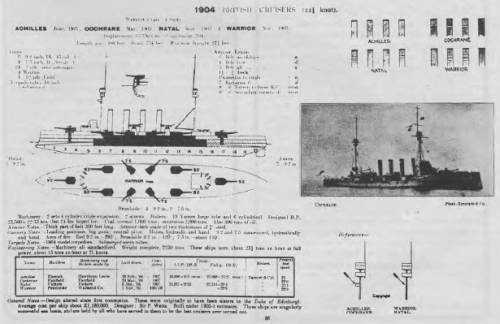

(HMS Achilles, HMS Cochrane, HMS Natal, HMS Warrior)