- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Singapore – a bastion of the British Empire, an impregnable fortress, fortified to withstand attack and prevent siege. With that in mind, thoughts of evacuation were therefore unnecessary.

What the British refer to as the Far East and Australians South East Asia was mostly dominated by the colonial powers of Britain, France and the Netherlands, with the ex-Spanish Philippines controlled by the United States. All these had considerable armed forces at their disposal, so a move by the Japanese to gain control of their oil, rubber and minerals was a dramatic undertaking without guarantee of success. But help was at hand.

Help from friends

On 11 November 1940 the German raider Atlantis encountered the Blue Funnel liner Automedon. When Automedon refused to stop she was raked by shells, killing the captain and his bridge team. A boarding party discovered a small weighted bag destined to have been thrown overboard. This contained top secret British Cabinet papers addressed to Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, Commander-in-Chief Far East. These explained the inadequacy of British forces to withstand a Japanese attack in the Far East and the Royal Navy’s inability to send a fleet in defence. The report also contained an order of battle for the defence of Singapore and the roles to be played by Australian and New Zealand forces should Japan enter the war.

In recognition of their importance these documents were entrusted to the prize crew of a recently captured Norwegian tanker, Ole Jacob, and immediately sent to Japan. The documents were delivered to the German Embassy which provided copies to Japanese authorities. This information, coupled with its own appreciation, convinced the Japanese War Office of the weakness of the British position (Robinson 2016).

At the same time, bowing to Japanese political pressure and possibly compounding foreseen weakness, Britain withdrew from its Chinese based garrisons at Shanghai and Tientsin and repositioned these regiments in Singapore, leaving the last east Asian outpost at Hong Kong alone and vulnerable.

Japanese expansion – South East Asia

War finally came with Japanese forces attacking the northern beaches of Malaya on 8 December 1941 – because of the dateline, one hour ahead of Pearl Harbor.Within days their attacks had extended to the Philippines and Hong Kong and through a pincer movement, down both sides of the Malay Peninsula. Britain responded, sending the battleship HMS Prince of Walesand the battlecruiser HMS Repulseplus four destroyers to intercept the invasion force. On 10 December both capital ships were lying on the sea bed off the east coast of Malaya with 840 dead and 2000 survivors seeking help from the beleaguered garrison.

As a prelude to events unfolding in Singapore in early December 1941 the Japanese Army’s 38th Division of over 50,000 men massed on the border between China and the British-leased New Territories. Opposed to them were about 8,000 men comprising two battalions of British infantry, two battalions of Indian infantry, and recently arrived, two battalions of Canadian infantry. Also on hand was the elite Indian manned Hong Kong and Singapore Regiment of Royal Artillery (HK&SRRA) and the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force. They were supported by seven obsolete aircraft, one elderly destroyer, two gunboats and eight motor torpedo boats (MTBs). Of the defensive forces only one British regiment and the Indians were prepared for operational service against a superior battle hardened force.

On Monday 8 December the Japanese crossed the border and carried out bombing attacks which completely destroyed the defending aircraft. Despite stubborn resistance and inflicting considerable casualties over 17 days of fighting, Hong Kong surrendered on Christmas Day 1941. The surviving garrison was marched into Japanese prison camps, some never to return.

The Japanese advance through the Malay Peninsula was unprecedented, and despite resistance by numerically superior defenders, appeared unstoppable. Accordingly, large numbers of families of servicemen and civilians were encouraged to leave. When the first bombs fell on Singapore the evacuation began in earnest with torrents of people desperately seeking passage in the next available ship. Many European and Eurasian women and children were evacuated before the end of December. A further 1500 women and children left early in the New Year and a final large contingent of 4000 departed in four passenger liners in late January 1942.

With the Japanese stranglehold over the Malay Peninsula there was no land exit, and after the last few RAF aircraft evacuated on 10 February the enemy controlled the skies. To prevent the remaining ships falling into enemy hands the senior naval officer, Rear Admiral Ernest Spooner, decreed that these must sail by 13 February.

That afternoon the Admiral called a meeting in his office at Fort Canning and told us that the decision that Singapore could not hold out had been agreed and orders had been given for the remaining naval and Air Force personnel, as well as selected Army technicians, to leave that evening (Pool 1987). The first embarkation was to be made as soon after dark as possible in order to allow all craft to clear Singapore and its approaches before daylight the following morning.

With an estimated capacity for 3000 personnel, 1800 spaces were allocated to Army, a few hundred to RN and RAF, and the rest to civil government. Following Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong as many female nurses as possible were to be evacuated. The AIF was given a disproportionately small allocation of 100 places to all ranks.

The Japanese were considered unprincipled in the conduct of war and there are many stories of survivors being killed, but there is another side to this story. The converted riverboat Wah Sui,not an internationally registered hospital ship, but painted white with large red crosses on both sides, had already been used to evacuate wounded from Singapore to Java and was now anchored in the harbour. Japanese authorities asked that she be moved away from the proximity of legitimate shipping targets. Wah Suiembarked a further 300 wounded, plus nurses, and sailed on 10 February. Although buzzed by enemy aircraft she was unmolested and made the safety of Tanjung Priok1.

Army officials were instructed that passes should go to men of outstanding ability with the intention of integrating this nucleus with Javanese troops in Batavia. Crowds now formed at the embarkation areas, some with passes and others without. Adding to the panic, they were being bombed. Radio Tokyo also broadcast messages that the British were not going to be allowed to escape in another Dunkirk.

Lieutenant Richard Pool RN, a survivor from Repulse,had been allocated to ML 310 and writes of his experiences (Pool 1987):

All day long columns of evacuees filed patiently along the approach road and on the wharf and gradually found spaces in the miscellany of craft which now thronged the dockside. Unfortunately, despite all efforts, some military at the point of a gun, forced their way on board. Every conceivable kind of boat, including yachts, was being pressed into service and my thoughts returned to those days of Dunkirk almost two years before. I could not help wondering why such an outflow of civilians, Europeans as well as Asians, should have been allowed at this late hour. I think many of us felt at the time that it was yet another example of the lack of firm leadership.

Michael Pether (Pether 2018), whose parents were in Singapore2, also describes the scene:

On the evening of 13 February 1942 as the Japanese Army tightened its encirclement of the central area of the city of Singapore the Allied troops and civilians endured constant bombing and artillery shelling – the city was in flames; thousands of dead bodies littered the streets and much of the city lay in ruins.

Government authorities had been tardy and inefficient in the evacuation of civilians until only a few days before and now, as the last vessels that could be remotely called ‘ships’ prepared to leave, chaotic scenes were taking place at the Singapore wharves as dozens of European and Eurasian civilian men, together with hundreds of servicemen from the UK, Australia, India and New Zealand scrambled onto any vessel departing that would take them. Most women and children who wanted to escape by ship had already gone – albeit that most of the ships which had left in the previous couple of days were doomed to be sunk.

Lynette Silver (Silver 1990) is more precise:

Rather than face the prospect of spending the rest of the war in prison, many chose to take the perilous journey across the sea to Sumatra, the only escape route now open. Colonels and brigadiers, civilians and civilservants,battle-hardenedwarriorsandarmy deserters intent on escape at any price, left in launches, junks, rowing boats, naval craft, in fact anything that floated.

The Plymouth Highlanders

Malaya and Singapore had an ample supply of defending forces, with a British Army supported by Australian and Indian troops, however, many of these had been hastily put together and quantity was not matched by quality. The Army’s strength was further limited by a lack of tanks, armoured cars and a shortage of anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. Air cover was in a worse state with 158 obsolete aircraft, including four RAAF squadrons, two of Brewster Buffalo fighters and two of Lockheed Hudson bombers.

An exception to the fighting force was the Second Battalion of Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, part of the Indian 12thBrigade, who had been positioned in Malaya in late 1939 to bolster the local forces. The Highlanders, who had trained in jungle warfare, fought well against the Japanese, until they too were overwhelmed. Fighting courageously, they were amongst the last to pass from the mainland over the Causeway and retreat into garrison Singapore.

The Highlanders, now down to 250 men, reformed with the addition of 210 Royal Marine survivors from the Prince of Walesand Repulse. They were whimsically known as the Plymouth Argylls (Plymouth Argyle is a football club).

When the first Japanese came ashore on Singapore Island on 8 February the thinly spread Australians defending the northwestcoast failed to halt the attack and the Argylls were send to help stem the tide in the brief Battle of Singapore. Survivors from this closely knit unit stayed together and some managed to escape whilst others were taken into custody. Brigadier Archie Paris with Major Angus Macdonald commandeered a private yacht Celia, skippered by Captain Mike Blackwood, and together with a number of other Highlanders made their way to Padang, only to join the ill-fated SS Rooseboom. From the composite Plymouth Argylls, 52 Highlanders and 22 Marines finally reached Colombo.

Singapore’s Dunkirk

Lieutenant Geoffrey Brooke served in the battleship Prince of Wales which sank on 10 December 1941. He survived this ordeal and when the opportunity came he and a number of his shipmates escaped in the river steamer Kung Wo. Brooke writes of his experiences in Singapore’s Dunkirk (Brooke 1989), but tragically this episode did not emulate the success of the English Channel crossing.

Another unfortunate consequence leading to confusion was that naval personnel responsible for coding and decoding signals were approved to leave the island aboard HMS Jupiterin the early hours of 12 February. As they had destroyed all code books the Rear Admiral Malaya was thereafter unable to read signals. While the presence of a Japanese Fleet, bound for Sumatra, was known to the Dutch it was nolongerpossibletopassthisinformationto Admiral Spooner. This proved disastrous as by dreadful coincidence the Japanese invasion fleet heading for the Banka Strait converged with the approaching fleet of small ships departing Singapore.

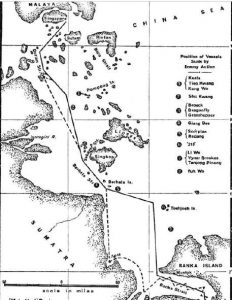

With the Japanese now within gun range on the opposite side of the Causeway a few thousand more persons escaped in an organized convoy on the night of 11/12 February. Afterwards a fragile fleet of forty-four independent unescorted sailings occurred on ‘Black Friday’ 13 February, with a few stragglers coming behind on 14 February. Over the final five-day period before surrender on Sunday 15 February 1942, about 5000 souls escaped but less than one in four made a safe landing, the rest being killed or captured.

On paper the escape plan seemed straightforward, a 20-mile passage over the Singapore Strait at night, and then laying up under cover of one of the numerous Netherlands East Indies islands, before island hopping to cover the next 60 miles and crossing the Banka Strait to the large island of Sumatra. The Japanese, however, were well aware of this deadly game of cat and mouse and had set a trap with aircraft overhead and ships guarding the Straits which caused havoc.

While particulars of all vessels involved in the exodus are incomplete the following participated.

| Ship | Captain | Crew | Passengers |

| HMS Changteh | LEUT D Findlay RNVNVR | 10 | 40 |

| HMS Dragonfly | LEUT A Sprott RN | 70 | 75 |

| Blumut – tug | 5 | 29 | |

| Celia | CAPT M Blackwood – Army | 2 | 15 |

| HMS Dymas | 5 | 16 | |

| Elizabeth – tug | LEUT Nigel Kempson RN | ||

| HMS Fanling – customs launch | LEUT J Upton RNZNVR | 5 | 47 |

| HMS Fuh Wo | LEUT N Cook RNR | 10 | 30 |

| HMS Giang Bee | LEUT H Lancaster RNR | 48 | 245 |

| Heather | LEUT St Aubin RNR | 4 | 50 |

| HMS Grasshopper | CMDR J Hoffman RN Rtd | 70 | 250 |

| Haig Hen | CAPT O Jennings (Army) | 4 | 25 |

| Hung Ho | LCDR H Vickers RNR | ||

| Hung Jao | LEUT R Henman RNVR | ||

| Hock Sieuw | Major G Rowley-Conwy RA | 3 | 166 |

| Kembong | 4 | 25 | |

| Kofoku Maru | CAPT Roy (Bill) Reynolds MN | 9 | 76 |

| Kuala | LEUT F Caithness RNR | 50 | 700 |

| Kung Wo | LCDR E Thompson RNR | 20 | 140 |

| HMS Li Wo | LEUT T Wilkinson RNVR VC | 24 | 60 |

| HMS Malacca | LEUT F Man RNVR | 15 | 62 |

| Mata Hari | LEUT A Carston RNR | 83 | 400 |

| Mary Rose | CAPT G Mulloch RN | 4 | 38 |

| ML 310 | LEUT J BULL RNZNVR | 16 | 28 |

| ML 311 | LEUT E Christmas RANVR | 15 | 57 |

| ML 432 | LEUT H Herd RNZNVR | 15 | 60 |

| ML 433 | LCDR H Campey RANVR | 15 | 60 |

| HDML 1062 | LEUT C MacMillan RNZNVR | 10 | 30 |

| HDML 1063 | LEUT M Innes RNVR | 10 | 20 |

| Panglima – HDML | LEUT H Riches MRNVR | 10 | |

| Pulo Soegi | LEUT A Martin RNZNVR | 10 | 60 |

| Redang | Captain S Rasmussen MN | 13 | 100 |

| Scorpion | LEUT G Ashworth RNVR | 70 | 250 |

| HMS Scott Harley | LEUT J Rennie RNR | 14 | 200 |

| Shu Kwang | CMDR A Thompson RNR Rtd | 25 | 300 |

| HMS Siang Wo | 90 | 142 | |

| Tandjong Penang | LEUT B Shaw RNZNVR | 17 | 220 |

| Tenggaroh | LEUT Whitworth MRNVR | 5 | 42 |

| Tern | 3 | 21 | |

| Tien Kwan | LEUT R Heale SSRNVR | 15 | 300 |

| Trang | LEUT H Rigden MRNVR | 10 | 71 |

| HMS Tapah | LEUT J Hancock MRNVR | 19 | 45 |

| HMS Vyner Brooke | LEUT R E Borton RNR | 47 | 250 |

| Unnamed lifeboat | Major M Ashkanasy AIF | 2 | 38 |

| HMS Yin Ping –tug | LEUT Pat Wilkinson SSRNVR | 14 | 62 |

| Total 45 | 890 | 4845 |

Michael Pether (Pether 2018) has identified another twenty or so small craft which attempted the treacherous crossing. In addition, HMS Laburnumwas badly damaged by bombing and she, together with HDMLsPenghambat(LEUT F Man RNVR) and Penyengat were scuttled at Singapore to prevent them falling into enemy hands. HMS Panjiwas also sunk by enemy gunfire at Singapore. In January 1941 a large component of the Australian Army’s recently raised 8th Division was posted to Malaya. An element of some 6000 men departed Sydney in the liner Queen Maryas part of Convoy US9 on 4 February 1941, arriving in Singapore two weeks later on 18 February. A further 5000 troops in Convoy US111B arrived at Keppel Harbour on 15 August 1941. Under the command of Major General Gordon Bennett, the force initially established its headquarters at Kuala Lumpur. Bennett had urged for specific territorial responsibility for his Division, and this resulted in an area which included Johore and Malacca, coming within his responsibility.

The Australian Army 8th Division in Malaya eventually reached about 15,000 men. An apt description of the commander, Major General Henry (Gordon) Bennett, found in a Veterans’ Affairs publication, (Moremon & Reid 2002) reads:

A prominent citizen soldier, he had proven himself in World War I to be a fierce fighter and leader, but he was well known for his prickly temperament, argumentative nature and proneness to quarrel. His relations with senior British commanders and staff in Malaya were, at times, strained, as he grappled to maintain control of the Australian troops.

Bennett’s independent spirit did not fit into the Allied command structure, however his Division generally acquitted themselves well against a seasoned enemy.

Immediately following surrender of the garrison by Lieutenant General Arthur Percival on the evening of Sunday 15 February 1942, Major General Bennett handed over his command to Brigadier Cecil Callaghan and executed an escape plan (Bennett 1944).

The General, accompanied by his ADC, Lieutenant Gordon Walker, and staff officer Major Charles Moses3plus some Malaysian officers arranged to hire a junk. When the junk did not arrive the ADC swam to a sampan and guided her inshore, allowing the party to cross to Johore. Here they met a Chinese who for payment agreed to take them to Sumatra. After four days at sea they were sighted by the Singapore Harbour Services Launch Tern which took the General and his two aides inshore. Later they were flown to Batavia and from there to Australia. The escape was not well thought of by other senior Army officers, and in parliamentary circles it was politely termed ‘unwise’.

Another well-known escape was of 65 Australian nurses aboard HMS Vyner Brooke which sailed on 12 February. Property of the Rajah of Sarawak, she was requisitioned by the Admiralty, lightly armed andgivenacoatofgreypaint.Sheretainedher civilian crew who were given naval reserve ranks, commanded by Captain Richard Borton. On sailing there were about300 passengers and crew. Just short of Sumatra she was bombed and sunk when about 150 survivors made Banka Island. Nearly all were captured by the Japanese and 21 nurses were summarily executed with a further eight dying in captivity (Shaw 2010). Only 24 Australian Army nurses survived the bombings, massacre and POW captivity.

HMS Yin Ping was a WWI vintage coal burning unarmed tug requisitioned into the local naval forces under the command of an Australian planter, LEUT Patrick Wilkinson SSRNVR. When ordered to leave Singapore she was heavily laden with 14 crew and 62 passengers. She also towed a motor launch Eureka, manned by a petty officer and two ratings. Her passengers included the skipper’s wife, a civilian nurse Alice Wilkinson, and 12 Dockyard personnel, plus 50 from the RAF and Army. Ying Ping was first bombed with some damage but continued to the Banka Strait where she was shelled by an enemy cruiser. She sustained casualties, was soon on fire and had to be abandoned before she sank. It is believed 32 survivors, some wounded, came ashore which included the captain; his wife Alice had been killed during the attacks. LEUT Wilkinson came through the ordeal of captivity as a POW. Alice’s nephew is CMDR Mike Storrs RAN Rtd.

The most positive escape concerns the ex-Japanese fishing vessel Kofoku Maruskippered by Australian master mariner turned mining engineer, William (Bill) Reynolds. In early December 1941 Malayan Police rounded up about 1200 Japanese and impounded their fleet of fishing vessels. A Royal Navy assessment of these vessels was scathing, finding them in poor repair and mostly unseaworthy, and many were later burned. Reynolds had other ideas and as a skilled sailor and engineer he ‘borrowed’ a vessel. With necessary repairs he found that the 1934 built fishing vessel Kofoku Maru (Happiness), with a copper sheathed teak hull and German diesel engine, was a very sound craft and he recruited eight Chinese to crew her. She was similar in size to a Navy HDML but narrower in the beam.

Reynolds made a successful voyage in her from Singapore to Sumatra, taking 76 evacuees. After seeking cover in mangrove river estuaries he worked with local Dutch officials in helping rescue many other evacuees from sunken ships who had become stranded on remote islands. In deference to his Chinese crew Bill renamed his vessel Suey Sin Fah,and armed her with a machine gun before sailing with refugees from Sumatra to southern India. Here she was acquired by the Australian Government, renamed Krait, and shipped back to Australia as deck cargo before taking part in her famous commando operations against Japanese shipping in Singapore (Silver 1990).

A least one ship put up a gallant fight against overwhelming odds, she was the converted ferry cum armed patrol boat, HMS Li Wo, under command of Temporary Lieutenant Thomas Wilkinson RNR. With a makeshift crew Li Wo cast off with 84 passengers and crew and made for the Banka Strait. She suffered air attacks with some damage but then sailed directly into a convoy of enemy transports escorted by warships. With the option of surrender or attack Wilkinson, with the support of his crew, chose the latter and sank one transport and damaged another before Li Wowas sunk. There were only seven survivors and Lieutenant Wilkinson was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Naval Relocations

With the decision taken to relocate major royal naval assets to Java, most naval personnel were evacuated in MV Empire Staron 12 February. This left Rear Admiral Spooner with three river gunboats, Dragonfly, Grasshopper andScorpion, under the command of retired Commander J. Hoffman RN and a squadron of seven motor launches (MLs) under the command of Lieutenant Commander H.Campey, RANVR, plus sundry other small craft.

The once proud naval base, HMS Sultan,was evacuated at the end of January and set on fire with personnel relocated to a hutted camp at Seletar. Those remaining of the ships’ companies from Prince of Walesand Repulse after successive drafts had been sent to other ships, among them two officers, LEUT G. Brooks and LCDR A.H. Terry, with about 200 men.

On the morning of 12 February naval personnel were told they would be embarking in half-a-dozen small ships later that evening. A trio of old Yangtze river steamers Kung Wo, Kualaand Tien Kuangwere crewed as naval auxiliaries: RNR officers Brooks and Terry, plus 100 men, embarked in the largest of these, Kung Wo.Others aboard Kung Wo were a five strong media contingent which included an attractive budding Chinese film actress, Doris Lim.

In the first few minutes of 13 February the headquarters ship Laburnum, signaling by Morse light,gave orders to sail. ML 310was waiting in the stream for Rear Admiral Spooner and Air Vice Marshal Conway Pulford to embark.

River Gunboats and Motor Launches

The Locust class river gunboats were relatively new steam turbine ships of 585 tons capable of 17 knots. They carried 2 x 4-inch guns, 1 x 3.7-inch gun and 8 machine guns, with a crew of 75 officers and men. Scorpionmade her escape on 9 February and suffered air attacks but was able to continue until encountering the Japanese cruiser Yuraand two destroyers when she was sunk. Of the few survivors eight were picked up by the Japanese and later six more were found by the steamer Mata Hari.

Dragonfly and Grasshopper sailed in company on 13 February with about 325 troops, bound for Sumatra. Both ships were attacked by aircraft in the Banka Straits with Dragonfly hit three times, sinking quickly. Grasshopperwas hit twice and set on fire but her captain managed to beach her on nearby Sebayer Islands. There was considerable loss of life and casualties from both vessels, and most survivors were captured.

Fairmile Motor Launches (MLs) were versatile small craft produced in their hundreds and served in most theatres during WWII. They displaced 85 tons, were 112feet in length, with a top speed of 20 knots. They were armed with a single 3 pounder gun and twin machine guns, plus depth charges. They had a crew of 15 and up to 60 passengers could be crammed onboard. A smaller version was the Harbour Defence Motor Launch (HDML).

A number of MLs and HDMLs had completed building at Singapore within weeks of the evacuation. These were MLs 432and 433and HDMLs 1062and 1063. Three other HDMLs for the Straits Settlement Volunteer Reserve (SSVR) were given names in lieu of numbers, Panglima, Penghambatand Penyengat.

After ML310 was attacked by enemy ships she grounded on Tjebia Island about 30 miles north of Banka Strait. To avoid capture, the senior officers came ashore before she was examined by a Japanese boarding party and her engines disabled. The Japanese let the other survivors go ashore and the wreck was used for occasional bombing practice. A US submarine S-39was sent to look for the survivors but they could not be found. In seeking help LEUT Bull and two others eventually made Java where they became POWs. Twenty-two others escaped the island after rebuilding a native vessel but were captured and returned to Singapore as POWs. The remaining nineteen men including the Executive Officer of ML 310, SBLT Malcolm Henderson RANVR, the Admiral and the Air Marshal died of disease when on the island.

On 13 February ML311was attacked and destroyed by enemy surface ships and two days later ML432 was captured when beached off Banka Island. ML 433 and HDMLs 1062 and 1063 and Panglima were sunk by enemy gunfire off Banka Strait.

Halfway House

Ideally the passage over open water was made at night and where possible vessels laid up in the day close to, or under cover of, islands. Rarely did this strategy work and the small and largely defenceless vessels fell easy prey to enemy air attacks. Most were damaged and many sunk with large numbers of casualties. Some did make landfall on a number of islands including Pompong Island (about 80 miles south of Singapore) where they escaped the wrath of their attackers.

While Dutch officials did what they could the local people, fearing reprisals by new masters, were not always helpful. After landing a tortuous trek began across mountainous terrain making for the west coast port of Padang.

The passage of Kung Woas described by LEUT Brooke may be regarded as typical:

After passing through our own minefield at first light we were soon discovered by enemy dive bombers. Kung Woalthough hit with considerable damage there was only one casualty, a Chinese stoker killed by shrapnel. With the ship’s engines irreparable and taking on water the Captain ordered abandon ship. With only two boats it would take several trips to get all personnel to some wooded islands about 5 miles distant. (Brooke 1989)

Kung Wo was able to disembark personnel on Pompong Island and afterwards found their two companions Kuala and Tien Kuang anchored close inshore. As the wreck of Kung Wowas still afloat bombers returned and sank her. They also bombed the other vessels which were set on fire and sank, suffering numerous casualties.

Those ashore on Pompong, with some supplies, were estimated at about 200 women and children, 30 to 40 civilian men and 400 from the three services, which included many with severe injuries.

On 16 February a small Dutch steamer Tandjong Pinang arrived and embarked the women and children and those who were critically injured, but it was sunk about 12 hours later with only 15 persons reaching land. The next day the irrepressible Bill Reynolds arrived in Kofoku Maru and took off a further 70 walking wounded.

Denis Russell-Roberts (Russell-Roberts 1965), an Indian Army officer and later POW in Singapore, whose wife Ruth died on Banka Island, provides an analysis of 47 vessels that escaped from Singapore. This shows nine sunk by aerial bombing, 13 sunk by ship gunfire, three scuttled, 13 captured and seven unaccounted for. Only two vessels were thought to have made their intended destinations. From Michael Pether (Pether 2018) we also know the auxiliary HMS Scott Harley safely made its destination of Tanjung Priok.

Padang

Padang was an important town serving the southwest coast of Sumatra, and the adjacent port was known as Emmahaven. By late February 1942 thousands of men, women and children were crowded here where they were prioritised for transshipment by the occasional merchantman and warships that called. There was then a further dangerous voyage through waters controlled by Japanese warships and submarines to the safety of Colombo for British, and Fremantle for the Australian, personnel.

The survivors who reached Padang had suffered greatly. They were malnourished and frightened, with morale and discipline at a low ebb. Dutch officials were appalled at their unruly behavior and could not wait to be rid of their unwelcome guests. A latter British War Ministry report described the behavior of troops as deplorable, having particular harsh words for a group of Australians, many of whom were deserters from Singapore (Weintraub 2016).

An early relief ship was the small Dutch steamer SS Rooseboom which loaded about 500 refugees, mainly British troops but some civilians. In the early hours of 1 March, while crossing the Indian Ocean, she was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-159. Only one lifeboat with a capacity for 28 persons was launched, into which 135 survivors crammed, including Brigadier Paris. A month later they were washed ashore having returned to within a hundred miles of their departure point. Only six were alive including Corporal Walter Gibson of the Argylls, who wrote of this ordeal (Gibson 2007), and we again meet the resolute Doris Lim, plus four unnamed Javanese crew.

Another vessel to escape from Singapore was SS Ban Ho Guan of about 1,700 tons with a crew of 10 and over 200 passengers including two officers and 100 other ranks from the AIF. Little is known about their escape but it appears unauthorised. The Ban Ho Guan also made Padang and was later bound for Fremantle. After sailing for one day she was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-4 with no known survivors. This tally possibly accounts for the largest number of Australian troops missing after release from Singapore.

An important ship to reach Padang was the cruiser HMS Dragon which embarked many evacuees. On passage she met the armed merchant cruiser HMS Kedah which had sailed two days previously laden with evacuees. As Kedah’s engines could not be repaired she was towed by Dragon and both safely reached Colombo.

Summary

The surrender of Singapore was the largest single wartime tragedy that shook the morale of Australians. This was the greatest known defeat of British forces in the distant Far East. It was also the greatest defeat of Australian forces, but much closer to home in South East Asia, our near north.

Much is known of this and the vain attempt by the Prince of Wales and Repulse to halt the Malayan invasion and, the subsequent incarceration of troops and civilians at Selarang and Changi. Much less is known about the planned escape of thousands of servicemen, civilians and women and children over the last few days leading up to the surrender. The flight from the island became a lottery with the odds stacked heavily against the escapees.

The escape from Singapore is perhaps best summarised by Lieutenant General Percival who wrote (Brooke 1989):

I regret to have to report that the flotilla of small ships and other light craft which left Singapore on the night of 13-14 February encountered a Japanese naval force in the approaches to the Banka Straits. It was attacked by light naval craft and by aircraft. Many ships and other craft were sunk or disabled and there was considerable loss of life. Others were wounded or were forced ashore and were subsequently captured.

The final naval evacuation from Singapore in February 1942 was a tragedy of epic proportions, resulting in death and misery with few redeeming features except the eventual safety of the few survivors. With the prevailing primitive instincts of escape and survival there were few heroes, with the exceptions of LEUT Thomas Wilkinson VC of HMS Li Wo for fearlessly engaging the enemy, and the courageous Captain Bill Reynolds4with his ironically named Kofoku Maru.

References:

Bennett, Lt General Henry, Gordon,Why Singapore Fell, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1944.

Brooke, Geoffrey, Singapore’s Dunkirk, Leo Cooper, London, 1989.

Carew, Tim, The Fall of Hong Kong, Anthony Blond, London, 1960.

Gibson, Walter, The Boat – Singapore Escape, Monsoon, Singapore, 2007.

Pether, Michael, Extensive research papers & web sites,Auckland, 2018.

Moreman, Dr. John & Reid, Dr. Richard, A Bitter Fate: Australians in Malaya & Singapore, Dec 1941 – Feb 1942, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra, 2002.

Pool, Richard, Course for Disaster – From Scapa Flow to the River Kwai, Leo Cooper, London, 1987.

Roberts, Janet I., The ‘Yachties’ Australian Volunteers in the Royal Navy 1940-45, Master of Arts Thesis – University of Melbourne, October 2007.

Robinson, Stephen, False Flags – Disguised German Raiders of World War II, Exisle Publishing, Wollombi, NSW, 2016.

Russell-Roberts, Denis, Spotlight on Singapore, Times Press, Douglas, IOM, 1965.

Shaw, Ian W., On Radji Beach, Macmillan, Sydney, 2010.

Silver, Lynette R., KRAIT – The Fishing Boat that went to War, Cultured Lotus, Singapore, 2001.

Silver, Lynette R., The Heroes of Rimau, Leo Cooper, London, 1990.

Weintraub, Robert, No Better Friend: One Man, One Dog & Their Extraordinary Story of Courage & Survival in WWII, Little Brown & Company, Boston, 2016.

Notes:

1 The official history records Wah Sui sailing with 120 wounded but Moreman and Reid (2002) say six nurses and 300 wounded; those onboard say there were between 350 and 450 passengers, many of whom may not have been wounded. The ship later sailed to Colombo and served as a hospital ship in Burma. Post war she returned to Hong Kong.

2 Michael Pether’s mother (Kathleen) and her baby daughter were evacuated from Singapore on Christmas Eve 1941 and his grandmother escaped on 12 February 1942, all reaching the safety of home in New Zealand. His father and grandfather were interned. Kathleen’s brother, Jack Clark, a member of the Malay State Volunteer Forces was killed in action.

3 Charles Moses served in the British infantry during WWI. After settling in Australia he became known as a sportsman and journalist. He joined the AIF in WWII; post-war he became General Manager of the ABC and was knighted.

4 Bill Reynolds, later working for American Intelligence, was landed behind enemy lines in Malaya in November 1943. Locals revealed his presence and he was captured by the Japanese and subsequently shot by firing squad. This brave man had refused to kneel in order to be beheaded. He was indeed a hero.