By Zuhal Sharifee

In the pre-Chernobyl and Three Mile Island world of 1962, nuclear power was widely regarded as a cost-effective, efficient, and relatively safe way to supply energy. This perspective led to the ambitious idea of placing a nuclear reactor in Antarctica, a plan that seems unthinkable today given the region’s ecological sensitivity. The supply of power to Antarctic research stations came with a logistical challenge. In the 1960s, shipping millions of gallons of fuel to the Antarctic was arduous and expensive: one litre of diesel cost the USN 12 cents a litre; by the time this was shipped to McMurdo, the cost had risen to 40 cents a litre.

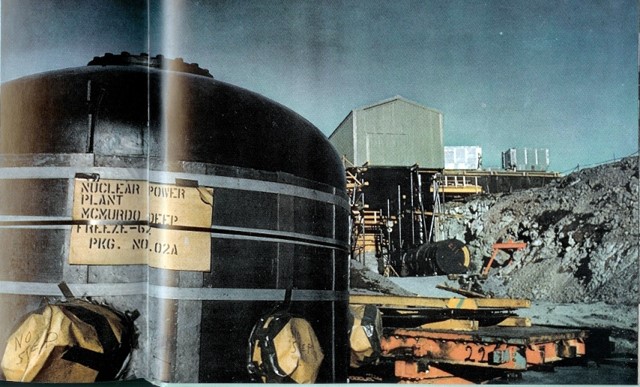

Building the nuclear reactor would not only pose a logistical solution to saving costs on transporting supplies but would also push a political agenda. President Dwight D. Eisenhower aimed to sell the idea of nuclear energy to the American public, through a program known as Atoms for Peace. The Atomic Energy Commission produced a study about the economic advantages of nuclear energy in remote places. The Pentagon contracted with Martin Marietta to build the McMurdo nuclear reactor for $US1.4 million, which eventually cost $US3 million.

The reactor was a portable plant designed by Martin Marietta and was known as a PM-3A portable medium powered unit (Long, 2011). It was an air-cooled, 1.75 MW pressurised water reactor designed to provide electricity, heat, and desalinated water for the US base using 93% enriched uranium fuel. PM-3A was not encased in concrete, instead its four main parts sat in steel tanks embedded in gravel and covered in a lead shield, which was necessary because in the frigid climate concrete would not cure. (O’Malley, 2024).

US Seabees completed site preparation in 1960-61 and construction of the plant the following year. The reactor went critical on 4 March 1962 and began providing power on 12 July 1962. A 25-man team used to run the plant were from the Naval Facilities Engineering Command. The plant was officially known as a ‘Naval Nuclear Power Unit’ which was nicknamed ‘Nukey Poo’ by the team.

Issues with the Reactor

Problems with the reactor arose from the beginning. In the first year a hydrogen fire broke out in the tanks which led to the reactor being out of service for eight weeks and McMurdo had to be provided with emergency diesel fuel. A 2018 article by ‘The Conversation’ describes the experience with the reactor: ‘A decade later, the optimism around the plant had faded. The 25-man team required to run the plant was expensive, while concerns over possible chloride stress corrosion emerged after the discovery of wet insulation during a routine inspection. Both costs and environmental impacts conspired to close the plant in September 1972’.

Decommissioning the plant presented a whole new dilemma. Decommissioned nuclear plants are entombed in concrete, but provisions in the Antarctic Treaty made this impossible. Consequently, the dismantled plant – along with some of the contaminated ground surrounding it – was bundled aboard the US Military Command Sea Lift vessel USNS Private John R Towle for shipment to a disposal site in California. In total 12,000 tonnes of irradiated gravel and soil were removed on supply ships, to be buried in concrete lined pits in the United States. (Maize, 2024).

Aftermath and Health Concerns

But that’s not the last we hear about the reactor, because in 2011 an investigation by News 5 Cleveland found evidence that McMurdo personnel were exposed to long-term radiation, and in 2017 compensation was paid to some American veterans of the base. A year later, New Zealand officials announced that it was possible that New Zealand staff were also affected. In 2020, the Waitangi Tribunal, a permanent commission in New Zealand hearing cases against the Crown, began an investigation into concerns about ill health suffered by four New Zealanders who served on McMurdo Base. This investigation is still ongoing.

Some of the Americans who served at McMurdo in the 1960s and 1970s contracted cancer and have since passed away. In one instance Jim Landy, an aviation flight engineer with the US Air Force, served eight tours at McMurdo between 1970 and 1981. Jim contracted cancer and died in 2012. For many years, Jim’s wife, Pam, battled the US Department of Veterans Affairs to recognise Jim’s cancers and receive survivor’s benefits (Harvie, 2018).

New Zealand’s anti-nuclear policy

The experience with the ‘Nukey Poo’ reactor may have significantly influenced New Zealand’s stance on nuclear issues. The origins of New Zealand’s nuclear-free movement can be traced back to the 1960s, where there was a push for an independent ethical foreign policy which grew out of opposition to the Vietnam War and environmentalism, which sought to preserve New Zealand as a green unspoilt land. Two main issues emerged for New Zealand during the early 1970s to mid-1980s: French nuclear tests at Mururoa and visits by American warships to New Zealand. The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior occurred in Auckland in July 1985. In 1984, New Zealand adopted a strict anti-nuclear policy, which included banning nuclear-powered or nuclear armed ships from entering New Zealand’s territorial waters (Coughlan, 2023). This policy has shaped New Zealand’s international relations, particularly with nuclear-powered allies like Australia and the United States.

Following Australia’s decision to join the AUKUS agreement to build nuclear submarines, Jacinda Ardern, the former prime minister of New Zealand, has declared that Australia’s new submarines will be banned from entering New Zealand’s long-standing nuclear-free zone. New Zealand’s anti-nuclear policy presents a significant challenge to the AUKUS alliance. The differing stances on nuclear power may create tensions in the traditionally close relationship between New Zealand and Australia.

However, if deployment of the nuclear submarines was imposed upon New Zealand, this could lead to escalating tensions with China. The Pacific nations desire a peaceful existence free from militarisation and fear that introducing nuclear weaponry could provoke a counter-response from China (Keen, 2023).

Despite its nuclear-free stance, New Zealand remains interested in the broader aspects of the AUKUS partnership, particularly in the space and technology sectors. As New Zealand’s Defence Minister Judith Collins stated, the challenges AUKUS presents to New Zealand’s space and technology sector are immense (Knott, 2024). This interest aligns with New Zealand’s commitment to technological advancement while maintaining its anti-nuclear principles. New Zealand does not seek to acquire nuclear-powered submarines or to be included in that aspect of AUKUS. Instead, the emphasis is on working closely with Australia and the United States on defence procurement to ensure interoperability in weapons and military technology.

Lessons Learnt

Nuclear power-generating reactors have evolved significantly since the 1950s. Initially, designs focused on pressurised water reactors, which use water as both coolant and neutron moderator. Over time, reactor technology varied to include gas-cooled, molten salt, and liquid metal-cooled reactors, each offering efficiency and safety improvements. Modern reactors emphasis passive safety and advanced fuel cycles, and these advancements aim to make nuclear power a more viable, safe, and economical part of the global energy mix.

The ‘Nukey Poo’ reactor serves as an example of the complexities and challenges associated with nuclear power, especially in ecologically sensitive regions like Antarctica. The initial optimism around nuclear energy as cost-effective gave way to operational challenges, environmental concerns, and long-term health impacts on personnel. These experiences contributed in shaping New Zealand’s strict anti-nuclear policy, a policy that continues to influence its international relations and defense strategies today.

References:

Coughlan, T. (2023). New Zealand Reminds Australia of Nuclear Weapons Ban, as Australia goes on Submarine Shopping Spree. The New Zealand Herald, 13 Mar. 2023.

Harvie, W. (2018). Kiwis fear cancer after working near leaky US nuclear reactor in Antarctica. Stuff. Kiwis fear cancer after working near leaky US nuclear reactor in Antarctica | Stuff

How nuclear power-generating reactors have evolved since their birth in the 1950s. (2015). The Conversation. How nuclear power-generating reactors have evolved since their birth in the 1950s (theconversation.com)

Keen, M. (2023). AUKUS in the Pacific: Calm with undercurrents. Lowy Institute. AUKUS in the Pacific: Calm with undercurrents | Lowy Institute

Knott, M. (2024). New Zealand moves closer to being included in part of AUKUS partnership. The Sydney Morning Herald. AUKUS: New Zealand moves closer to being included in part of partnership (smh.com.au)

Long, T. (2011). Nuclear Age Comes to Antarctica. March 4, 1962: Nuclear Age Comes to Antarctica | WIRED

Maize, K. (2024). The cold sad tale of ‘Nukey Poo’. The cold sad tale of ‘Nukey Poo’ – The Quad Report

O’Malley, N. (2024). The dirty history of ‘Nukey Poo’, the reactor that soiled the Antarctic. Nuclear power: How ‘Nukey Poo’ soiled the Antarctic (smh.com.au)