- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Naval Intelligence, History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Richard Breckon

‘My Darling Mother,

I am writing this in a hurry. All letters are being opened and so I’m getting this posted by a civilian lady who is the mother of my chum. …I am A1 and am transferred on to the Armadale … I am very lucky in getting this letter off, as we are not permitted to say what boat we are on, or when we sail or anything…’

Private Frank Kirby, a 19-year-old warehouseman from Melbourne, wrote the letter to his mother on board a troopship in Albany’s harbour, Western Australia, where the ships had gathered prior to sailing as a convoy. By late October 1914, when Kirby wrote his ‘illegal’ letter, the soldiers were under instructions to post unsealed letters to facilitate censorship. Kirby broke the rule, but, as explained below, he did not evade the censor entirely.

The Australian Imperial Force, comprising three infantry brigades and one light horse brigade, departed Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney, and Adelaide in mid-September to rendezvous at Albany to take on coal and water. After being joined by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, the convoy departed on Sunday 1 November 1914. The 28 Australian ships carried 21,529 troops and 7,882 horses, and a further 10 ships carried the New Zealand forces of 8,188 troops and 3,820 horses. The 38 troopships were protected by four warships.

Before the convoy left Australia, mail that was posted on board the troopships was taken to HMAT Orvieto1 for examination by the censors. A strict censorship of soldiers’ mail was imposed to prevent any mention being made of the names and movements of the ships. The importance of the rule was underlined by an incident involving the Emden. The German raider had passed the convoy near the Cocos Islands at night, but did not detect the ships because they had turned off all lights.

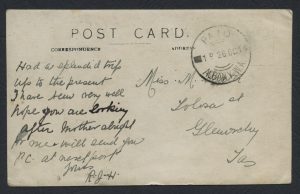

Because stamps were not readily available on the ships, soldiers were told to write across the front of their postcards and envelopes, ‘Stamps not available – on service with Australian Imperial Force’. The amount of postage for letters – up to a half ounce (14 grams) – and postcards was 1d (one penny). A postal regulation required the addressee to pay for postage on delivery, if it was not practicable for the sender to affix stamps. Interestingly, many postmen delivering the (unstamped) letters and postcards to the families and friends of the soldiers did not collect the 1d postage owing. By ignoring the postal regulation, they delivered a patriotic gesture.

Private Kirby had not counted on the vigilant staff at Albany Post Office. They were asked to intercept letters from soldiers that had been posted directly, and to hold these letters back. Along with the mail posted on the troopships, the soldiers’ mail was taken to the Perth General Post Office. The mail was embargoed until 16 November, when it was processed for onward transmission and delivery. By this stage, the convoy had moved well away from Australia. It was censorship by embargo, making direct censorship of the mail unnecessary.

A particular aspect of censorship involved the publication of photographs of troopships departing from Port Melbourne in the Argus newspaper on 28 October, and again on the following day. The publication was authorised by the military censors, but the naval authorities objected. An order was obtained to prevent all mail (from anywhere in Australia) being despatched to the Dutch East Indies, Singapore and the Philippines for seven days, and for newspapers being sent to any overseas destination for 14 days – another example of censorship by embargo.

As the convoy moved towards Ceylon, the soldiers’ mail was subjected to censorship and bagged onboard. The censors’ hand-stamp, ‘AIF Passed by Censor’, was applied to the front of envelopes and postcards and the mail bags transferred to the P&O or Orient Line mail steamers travelling to Australia. On arrival, the mail was taken to Sydney or Melbourne for postmarking before being delivered. This occurred about four to five weeks after the mail was handed over in Colombo and Aden. The mail posted on board ship was carried free of postage to the point of delivery.

Only a few of the soldiers had the privilege of shore leave at Colombo. Generally, officers and senior NCOs were allowed ashore and other ranks remained on board ship. In Aden, there was no shore leave. Those who went ashore in Colombo could write letters home through the normal postal service, but the mail had to be prepaid at the appropriate rate of postage in Ceylon. This mail avoided the convoy’s censors, but it was still subject to censorship on arrival in Australia.

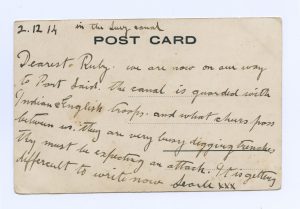

On reaching the Red Sea, the British War Office gave orders for the convoy to proceed to Egypt for disembarkation instead of travelling to England, as was originally planned. The first opportunities for the troops to post mail were at Suez and Alexandria during the first week of December.

The regular receipt and despatch of mail was a very important boost to the morale of the troops and their families, and friends at home. For this reason, Major General W.R. Birdwood, commander of the Australian and New Zealand forces, concluded his talks to the troops with some advice: ‘And, mind, whatever you do, write regularly to your mothers and wives and sweethearts – because, if you don’t, they will write to me.’

Bibliography:

Haynes, B & Pope, B: Western Australia: The Forces, Prisoner of War and Censor Mail, Perth, 1997

- HMAT Orvieto was the senior ship of the fleet which carried Major General Bridges and his staff of the 1st Division plus the official war correspondent C.E.W. Bean.