- Author

- A.N. Other and NHSA Webmaster

- Subjects

- History - post WWII

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 1994 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Battle for Falkland Islands – 1982

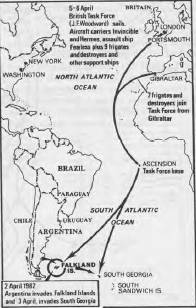

The Argentine seizure of the Falkland Islands (las Islas Malvinas) on 2 April 1982 took place at a time when the British Royal Navy was under threat of cuts imposed by the new Secretary of State for Defence, John Nott. Despite warnings from the Royal Navy that the ice patrol ship Endurance was a cost-effective reminder to Argentina not to press her claim to the islands with excessive force, she was listed for early scrapping. At the same time the ruling military junta in Argentina was under internal pressure from popular unrest at economic problems, and when they saw what appeared to be the first sign that Britain was at last prepared to withdraw her claim to the islands, they decided that the time had come to use force to accelerate the process and at the same time divert public attention to an external issue.

Both sides paid dearly for their miscalculations. The British government, outraged at what they saw as a violation of international law, immediately dispatched a powerful task force to repossess the islands, while a divided group of senior Argentine military officers tried to fend off or escape the consequences of their actions by haphazard diplomatic efforts. One by one the diplomatic initiatives collapsed, as they came up against two hard facts: the British regarded the islands as theirs legally, and the Argentine military junta’s precarious prestige could not survive a climb-down.

We now know that the junta finally accepted that hostilities were inescapable when on 1 May a single RAF Vulcan bomber flew from Ascension Island to bomb the runway at Port Stanley. Believing that the British intended to bomb Buenos Aires, the Argentine high command gave permission for two naval Super Etendard aircraft to launch a missile strike against the British next day, in the hope that a severe loss would force the British task force to withdraw. A small British detachment had already recaptured South Georgia, 800 miles beyond the Falklands, but the facilities there could not support a fleet, and on the advice of Admiral Anaya the junta believed that the British would soon be forced back to Ascension.

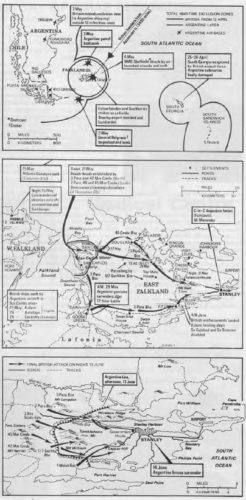

The Super Etendard sortie was launched but was abandoned when the two aircraft failed to rendezvous with their tanker, but in the meantime the nuclear hunter-killer submarine HMS Conqueror had found the old cruiser General Belgrano steaming just outside the Total Exclusion Zone which the British had proclaimed around the islands. With-some units of the task force already on the south-western side of the islands, and two Exocet-aI’med destroyers escorting the cruiser, Admiral John Woodward and his superiors at Fleet HQ, Northwood, decided that the Belgrano task group was a threat and, after consultation with the British government, Conqueror was given permission to sink her. Some 350 of the Argentinian crew went down with the ship or succumbed to exposure before they could be rescued.

Two days later the Super Etendards made another sortie and this time one of their AM39 Exocet missiles hit the air defense destroyer Sheffield. A fierce fire took hold and about five hours later the fire parties abandoned the ship. In fact the gutted hulk stayed afloat for another six days but when the weather worsened she was scuttled.

Contrary to Argentine predictions the British did not withdraw, and during the next 17 days Sea Harrier strike aircraft and individual ships probed the defenses, bombarding Port Stanley’s airfield, sinking any Argentine ships still in the Exclusion Zone and ‘inserting’ SAS and SBS forces ashore. On the night of 15 May a raid on Pebble Island destroyed aircraft and fuel dumps, and incidentally confused the defenders about the point of assault. At dawn on 21 May the main land forces under Major General Jeremy Moore RM landed at San Carlos on the western side of East Falkland. They had achieved the ideal amphibious landing, taking the defenders by surprise and not losing a man.

After a week to consolidate the troops broke out of the bridgehead and captured Goose Green, but the speed of advance was hampered by lack of heavy-lift helicopters. Air attacks by Argentine Air Force Mirage fighter-bombers and Navy Skyhawks had sunk two frigates and damaged a number of ships in San Carlos Water, culminating in a massive series of raids on 25 May. Once again the Super Etendards were in action and their Exocets crippled the big transport SS Atlantic Conveyor. In the fire which engulfed her three Chinook and 12 Wessex helicopters were destroyed, as well as a vast quantity of military stores.

With only one Chinook surviving to carry the largest loads to the forward battle zone the decision was made to economize on carrying capacity by getting the Marines and Paras to make their way to Port Stanley on foot – the epic ‘yomping’ and `tabbing’ (as the soldiers’ slang described it) which outflanked the Argentine defenses. Thereafter the pressure on Port Stanley was inexorable, marred only by a setback at Bluff Cove on 8 June. In a rash attempt to speed up the advance two landing ships, Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram moved detachments of the Welsh Guards into Bluff Cove in daylight. There they were caught by Skyhawks which set both ships on fire. In the confusion some 50 soldiers died and the Sir Galahad was so badly damaged that she was subsequently scuttled.

While the troops tightened their grip on Port Stanley the task force continued to supply them with their munitions and supplies, and the two carriers Hermes and Invincible flew off constant Sea Harrier strikes. On 31 May the Argentines made their last attempt to break the naval stranglehold. A force of six Skyhawks and two Super Etendards with their single remaining Exocet missile attempted to sink the Invincible but ran into a well prepared defense. The destroyer Exeter shot down two Skyhawks and in the confusion the Etendards were forced to make their attack at maximum range. The pilot who fired the Exocet mistook the still smoldering hulk of the Atlantic Conveyor for a carrier, and thus wasted the last of these deadly weapons.

The last major naval engagement was on the night of 11 June, when the destroyers Exeter and Glamorgan bombarded the Port Stanley defences. As they moved out to sea an Exocet missile mounted on shore was fired at them. Fortunately the Glamorgan was alert and turned her stern to the approaching missile to minimize any damage. The missile did not explode but wrecked Glamorgan’s helicopter hangar and after auxiliary engine compartment, killing 13 and injuring 14 men.

Port Stanley surrendered on 14 June. Casualties had been remarkably light, roughly 250 British and 1000 Argentines, about 75 percent lower than the British had estimated at the start of the campaign. The long-term future of the Falklands remains unsure but to prevent another Argentine attack the British have left a powerful garrison in the island and have built an airport capable of handling wide-bodied transport aircraft. Port Stanley’s harbor facilities were also improved to permit RN warships to spend the winter ‘down South’. The strategic value of the islands now obscures any considerations about the welfare of the 1800 inhabitants.

Not only the Royal Navy but other Western navies learned important lessons from the Falklands. The danger from sea-skimming missiles was already known but the need to deploy electronic countermeasures promptly was not widely understood. Nor was the risk from smoke in a damaged ship appreciated; new designs emphasize preventing smoke spreading and the elimination of materials which generate toxic smoke. Designs of antimissile guns were under development before 1982 but now they are widely used.

On the positive side the British Sea Harrier STOVL (short take off/vertical landing) aircraft proved a match for Mirage IIIs capable of flying at twice the speed, and their heroic air defense decimated the Argentine Air Force and Navy strikes sent against the task force. The Argentine Air Force was handled bravely but failed to drive away the British; the Navy was handled very badly, and after the sinking of the General Belgrano returned to harbor.

The British devoted considerable energy to countering the threat from submarines but out of four boats available to the Argentines one was already stripped for scrapping, one was sunk while running reinforcements into South Georgia and a third was laid up with machinery trouble. Claims were made that the fourth, the San Luis, had torpedoed HMS Invincible with a ‘dud’ torpedo, but the submarine captain’s own testimony revealed that he fired three torpedoes in 34 days, two at surface escorts and one at a submarine, all apparently at long range and without success. British submarines proved a major deterrent to Argentine surface forces, and also played a useful role in landing and recovering SAS and SBS patrols.

One of the best known of these was the cruise liner Canberra, shown here during a refueling operation, which became a troop transport with a minimum of conversion work.