- Author

- Swinden, Greg

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Sydney I

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Greg Swinden

The original version of this article was first published in the Supply Newsletter and has been reproduced with minor amendment. Also included is a copy of a letter by Eric Kingsford-Smith to his mother, the original of which is held by the Australian War Memorial. This letter is an important eye witness account of the Battle between Sydney and Emden.

Eric Kingsford-Smith was born in Brisbane, Queensland on 27 February 1887, one of eight children born to William Charles Smith (Banker) and Catherine Mary Kingsford (daughter of Richard Kingsford who was a Member of the Legislative Assembly of Queensland). The family later took the hyphenated name Kingsford-Smith. Eric’s younger brother Charles Edward (1897-1935) later became the famous Australian aviator Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith.

Eric was educated in Brisbane, Sydney and Vancouver (the Kingsford-Smith family lived in Canada during the period 1903-1907 when William worked for Canadian Pacific Railways). In 1904 Eric joined the British Columbia Telephone Company and was employed as an assistant accountant. He returned to Australia in 1907 and worked as an accountant in New South Wales before joining the Merchant Navy. He later qualified as a Purser and served in the passenger liners Zealandia and St Albans. Eric Kingsford-Smith joined the RAN on 26 August 1912 as an Assistant Paymaster (Probationary) and his first ship was the training cruiser HMAS Encounter. He served in her for only a few months before joining the coastal patrol vessel HMAS Gayundah where he served throughout 1913. In January 1914 Eric joined the new cruiser HMAS Sydney and served in her until March 1917.

Eric Kingsford-Smith married Mary Josephine Connah, with Church of England rites, at St Jude’s Church at Randwick, Sydney on 24 January 1914 and they later had two children. The family lived in the northern Sydney suburb of Turramurra.

After war broke in August 1914, Sydney took part on the capture of German New Guinea in September and the destruction of the German cruiser Emden at the Cocos Islands on 9 November 1914. Sydney then operated in the Caribbean and off the east coast of the United States during 1915-16 before proceeding to the North Sea in September 1916. Eric was promoted to the rank of Paymaster (Lieutenant) on 26 August 1916.

The cruiser was based at Rosyth, Scotland and conducted patrols in the North Sea throughout the winter of 1916-17 which was noted for its very bad weather. Kingsford-Smith left Sydney in March 1917 and returned to Australia where he was posted to the depot ship HMAS Penguin. His duties here were mainly administrative tasks and in early 1919 he became the Secretary to Captain J.C.T. Glossop who was the Captain in Charge of the Naval Depot. Glossop had also been Eric’s Commanding Officer during his service onboard Sydney.

In April 1920 Eric joined the cruiser HMAS Melbourne as the ship’s Paymaster (and Fleet Accountant Officer) and served in her until December 1923. He was promoted to Paymaster Lieutenant Commander in August 1921. At the time he served in Melbourne the ship conducted the dramatic rescue of the 18 passengers and crew from the schooner Helen B. Sterling when the vessel foundered in a storm north of New Zealand on 22 January 1922.

Eric returned to Penguin in January 1924 where he was the ship’s Paymaster Lieutenant Commander until July 1926. He then joined the Destroyer Depot and Fleet Repair Ship HMAS Platypus where he served until January 1927. He returned to Penguin but was injured in a fall onboard and punctured a lung; which was later removed. As a result he was medically retired from the Navy in November 1927 and placed on the Retired List of Officers. On 31 December 1929 he was promoted to the rank of Paymaster Commander (Retired List). Eric Kingsford-Smith then followed a career as an accountant and lived in Sydney.

When war broke out in September 1939, Eric Kingsford Smith returned to naval service and was posted as the Base Accounts Officer of the Sydney Naval Depot (Penguin). He remained in this role from September 1939 until February 1941. He then assisted in the re-commissioning of the Repair Ship Platypus; which had been in reserve for several years. In early April 1941 he returned to Penguin and was a member of the staff of the Flag Officer Commanding the Sydney Area until July 1945.

In the final days of World War II Kingsford-Smith served in the Pacific Theatre. From August 1945 until January 1946 he served at HMAS Basilisk (Port Moresby), HMAS Madang (Madang) and HMAS Gilolo (Moratai in the Halmahera Island group); where he was briefly the Command Supply Officer for the Naval Officer Commanding the Moluccas Area.

Kingsford-Smith returned to Sydney in January 1946 and rejoined Penguin. He was finally demobilised from the RAN on 16 September 1946 and then placed on the Retired List on 27 February 1947 at the age of 60. In retirement he continued to live with his family in Turramurra and was a member of the board of directors of Butler Air Transport Limited. He was also a highly talented magician and kept his grandchildren entertained with a variety of magical tricks. His wife Mary died in 1965 and he then lived with his daughter Judith in Wahroonga.

His son Sydney Kingsford-Smith, who had also served as an officer in the Navy during World War II, operated a coffee plantation on the Dunantina River (New Guinea) during the 1960s and Eric was a frequent visitor. It was during a visit there that he died in light aircraft crash at Mount Hagan, on 27 July 1968. His remains were returned to Australia for cremation. It is ironic that Eric and his more famous brother Charles Kingsford-Smith both died in light aircraft crashes.

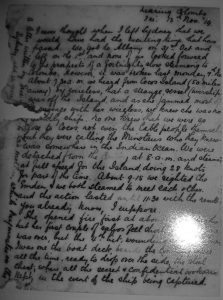

The original of this letter, dated Friday 13 November 1914, is held by the Australian War Memorial. This provides an important eye witness account of the Battle of Cocos between HMAS Sydney and SMS Emden which had occurred only four days previously.

Nearing Colombo

Friday 13th Nov. ‘14

I never thought when I left Sydney that we would have had the exciting time that has passed. We got to Albany on 31st October and left on the 1st and none of us looked forward to the prospects of a fortnight’s slow steaming to Colombo. However it was broken last Monday 9th Nov. About 7.30 a.m. we heard from Cocos Island (50 miles away by wireless that a strange vessel (warship) was off the island, and as she jammed most of the message with her wireless, we knew she was no friendly ship. No one knew that we were so close to Cocos, not even the cable people themselves but they were calling Minotaur who they knew was somewhere in the Indian Ocean. We were detached from the convoy at 8 am and steamed at full speed for the Island, doing 29 knots for part of the time. About 9.15 am we sighted the Emden & we both steamed to meet each other and the action lasted until 11.30 with the result you already know, I suppose.

She opened fire first at about 12,000 yards but her first couple of salvos fell short. The next one was over, but the 4th hit, wounding about six men. I was one (sic) the boat deck, beside the conning tower all the time, ready to drop over the side the steel chest, where all the secret and confidential books were kept, in the event the ship being captured.

I thus had a good view of the whole action. My word Mummy, I will never forget the sound of shrapnel and other shell shrieking and bursting all around. You seem to hear it coming from a good way off, shortly after the flash from the guns, & then with a sort of whistling shriek it whizzes overhead or to the side & the water it kicks up on hitting the sea goes up about 50 feet.

It is a ghastly sound & it was continuous only varied by some of these shells bursting & the sound of countless pieces hitting all round.

We picked up the Emden’s range after our third salvo & did a lot of damage. After about half an hour down came her first funnel, followed shortly after by a second. She was getting very badly punished where we hadn’t much damage done to us. I had three rather close calls. A wire stay i was resting my hand on was cut through about a foot above my hand, then i felt a knock on my arm & a piece of shell about an inch square, bounded from it on to the deck. It was a spent piece & had very likely hit the conning tower first, anyway, it hardly bruised my arm. I have the piece now. Then another piece grazed my leg above the ankle leaving a nasty red mark & making leg and foot pretty sore and bruised for a day or two. Another shell whizzed past about 10 feet away & a few seconds later, I saw a big red pool & splats of blood scattered about where it had gone right through from left to right of an AB’s chest. I couldn’t see him as a canvas screen was between us but I could see his traces. Another shell went clean through the lower bridge. Just over my head carrying away a stanchion & splintering wood work everywhere. Then another went through the upper bridge (or fore control as it is called) just missing the captain & lieutenants & taking the leg off at the thigh of the man working the range finder. The poor chap had to lie for 25 minutes without attention before a stretcher party could come to him. Naturally he died. I had to go up to the Captain shortly after & the fore control was simply soaking in blood. It must have been an inch deep on the deck & pieces of flesh and bone were over everything. A melonite shell burst just behind a petty officer at another gun tearing out half the small of his back & sending a splinter clean through his lung. The poor chap didn’t die until the next day and suffered horribly. Altogether we had two killed on the day itself & two more died next day & nine wounded, not counting minor wounds.

After the Emden’s second funnel went, we kept plugging at her & presently down came her foremast & last funnel. Then we knocked a huge hole, about six feet square, in her side, so that in order to avoid sinking, she ran herself ashore, on North Keeling Island.

Her flag was still flying, but we left her for a time to get her collier, which had been standing off during the engagement & was trying to get away. We chased her & made her heave to & haul down her colours. A Lieutenant & I boarded her, with an armed guard, but found that the prize crew the Emden had put on board her, had opened the sea cock & she was sinking. She was a British collier – The Buresk of London, that the Emden had captured six weeks before. We couldn’t save her, so we took off the officers & crew, & put three shells into her, to make sure of her & came back to the Emden.

Her flag was still flying, so we made a signal to her, to surrender. She didn’t reply so we put another dozen lyddite shells into her at close range, it was awful the damage we did. She was in flames from fore to aft. A couple of shells burst right in the engine room killing 50 & some more on the fore-castle.

She then surrendered. We went back to Direction Island (the cable station) 15 miles away & got another surgeon & came back early the next morning & started getting off the wounded and prisoners. Out of about 400 souls on board only 190 were left & of those a good seventy were wounded. It took us all day to get them off. The Captain & Prince Franz Joseph of Hohenzollen (a nephew of the Kaiser) were amongst the last to come off, both were unwounded.

I didn’t go on board here, but the tales were pitiful. She was simply a confused mess of twisted iron, no wood planking left; it had all been burnt. The decks were simply strewn with heads, arms & legs & were simply swimming with blood. All the guns were out of action & around some whole gun crews had been blown to bits, & pieces of them were splattered on the gun mechanism. The survivors couldn’t bury all the dead & when our party got on board they found a fire lit on the fo’castle & a huge pile of bodies awaiting a funeral pyre.

Emden’s Captain had this as the only thing he could do. Down below the officers’ quarters & Captain’s Cabin were simply unrecognisable, being shot to pieces & pieces of bodies were scattered everywhere. We were lying about ¼ mile from her & dead bodies were continually floating past. There were 18 men on the Island, who had jumped overboard when the ship struck & managed to get ashore through the surf, so we went around to the lee side of the Island to get them.

All but five turned up & they were mostly wounded so we landed a party to look for them. They had to stop ashore the night as they could not find the men. At daylight we got them. Of the 18, three had died on the Island from thirst, or rather from drinking salt water. The others simply rushed the water on board. One man drank 9 cup fulls straight off. The Germans must be awful fools as the Island simply teems with coconuts.