- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval Aviation, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

…brought to life with memorabilia from an Australian air ace found on Queensland rubbish tip

By Jim Craigie

The Great Find

A World War I pilot’s helmet worn by Australia’s greatest air ace is at last on public display, in the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Nowra, NSW, along with other memorabilia belonging to Captain Robert Alexander Little. All of this material belonging to Little, who served with the Royal Naval Air Service during the Great War, was discovered early in 2012 on a rubbish tip in the curiously named small town of Texas in Queensland, close to the NSW border.

While fossicking through the tip a collector, who wishes to remain anonymous, came across a leather Gladstone-style bag. It was taken home and put aside. Some 18 months later the collector, at last checking the contents, found a leather helmet, a silk shirt, camel-hair vest, two pairs of long-johns, a cravat, some pressed flowers and a pair of goggles.

In the lining of the helmet was a piece of metal which on closer inspection was found to be a ‘lucky’ gold sovereign wrapped in a photograph of a baby boy. The helmet was marked R.A. Little, Windsor, Victoria, Australia, and with the Latin logo ‘Deo Patriae Litteris’ (For God, for Country and Learning). This is the motto of Scotch College, Melbourne.

Thankfully, the potential importance of the material was recognised. The finder contacted Gareth Morgan, president of the Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians, who in turn sought advice from Mike Rosel, author of Unknown Warrior (the story of Australia’s greatest fighter ace Captain Robert Alexander Little). He confirmed the likelihood of the Gladstone bag contents being genuine. Next, Mr Terry Hetherington, manager of the Fleet Air Arm Museum, travelled to meet the finder, who agreed that the FAA Museum was the best place to display this remarkable memorabilia.

The chance finding in a far corner of Queensland awakened interest in two remarkable shooting stars that lit up the sky over Europe during WW I. Their war was short – from November 1916 to May 1918 – but spectacular. The two stars were Captain Little from Melbourne, and his naval fighting scout, the Sopwith Triplane. Although only about 140 were built, the Triplane was one of the most successful aircraft of the 1914-18 war. Its qualities undoubtedly helped Captain Little become Australia’s top-scoring fighter pilot, albeit serving with the Royal Naval Air Service and later the Royal Air Force. Captain Little was easily our top-scoring air ace with an official tally of 47 victories. He was awarded DSO & Bar, DSC & Bar and the Croix de Guerre.

Early Life: Not good enough for the Central Flying School

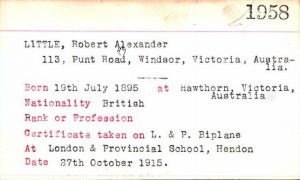

Little, born on 19 July 1895 at Hawthorn in Melbourne, felt compelled to sail to England in 1915 to learn to fly at his own expense, as the Central Flying School at Point Cook at that time would accept applications only from serving army officers. Little had been educated at Scotch College before entering his father’s medical and surgical books business as a salesman.

Entry into the Royal Naval Air Service

The determined 20-year-old earned his pilot’s certificate from the Royal Aero Club at Hendon on 27 October 1915, and entered the Royal Naval Air Service as a Flight Sub-Lieutenant in January 1916. After training at Eastchurch and service at Dunkirk on bombing raids he was transferred to No 8 Naval Air Squadron in October 1916 for scout pilot duties on the Western Front. On a more personal note, he’d had time to woo and marry Vera Gertrude Field at Dover in England. The squadron at that time flew Sopwith Pups. Little joined ‘B’ Flight which was commanded by another Australian, Flight Commander S.J. Goble. On 11 November Little, flying a Pup, shot down his first enemy aircraft, an Aviatik CI, over Beaumont-Hamel.

When the squadron re-equipped with the spectacular three-wing Sopwith Triplanes in February/March 1917, Little’s score stood at nine. He’d been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for ‘conspicuous bravery in successfully attacking and bringing down hostile machines’. In retrospect it would seem that Little, who acquired the nickname ‘Ricki’ (after Rudyard Kipling’s cobra-killing mongoose ‘Riki Tiki Tavi’) and the Sopwith Triplane nicknamed ‘Tripe’ were made for each other. His keen judgment, quick thinking, expert marksmanship and indomitable courage were admirably complemented by the Triplane’s manoeuvrability and speed.

Little preferred ‘infighting’ and would fire only at point blank range. Once he flew so close to an Albatros biplane that he collided with the enemy’s tailplane and had to land with a cracked undercarriage. At another time, after his guns jammed, Little purposely ran his wheels over the top wing of a DFW two-seater in an attempt to force it down.

‘Naval Eight’, as the squadron was known, was in the thick of the fighting and was opposed by the German Jagdstaffel 11 commanded by Manfred von Richthofen. But Little was not one to be deterred by reputation. On 7 April 1917 he single-handedly engaged 11 Albatros scouts which he outflew and outfought for almost 30 minutes. Watchers on the ground, including von Richthofen himself, later testified to the superb tactics of Little and his control of the situation. To Little, an enemy aircraft was something that should not be in the sky. Scouts and two-seaters of many makes – Halberstadts, DFWs, Aviatiks, LVGs, Fokkers and Albatros aircraft – all fell to his guns. In most cases the impact of his close-in firing caused wings, tails and even fuselages to break up in the air.

On 24 April 1917, Little engaged a DFW CV, forcing it to land. He then followed the German aircraft down to claim it as captured and personally take its crew prisoner at gunpoint. The Australian flipped his own plane in a ditch after touching down, however, prompting the surrendering enemy pilot to suggest: It looks as if I have brought you down, not you me.

Naval Eight’s conversion to the Sopwith Triplane in April saw Little begin to score heavily, eventually registering 24 victories in the Triplane to bring his total up to 28, including twin victories four times in a single day. He was the squadron’s top scorer with the Triplane, mostly in one particular airframe, N5493, that he christened ‘Blymp’, after the nickname of his baby son. He personalised this aeroplane by having the pilot’s seat moved forward to improve manoeuvrability and with that speed, and by adding streamers from the wing struts in the cardinal (red), gold and blue of his old school Scotch College.

The Unit then began flying Sopwith Camels, in which he scored a further 10 kills in July to make 14 all-up for the month. When he rotated back to England for rest, he was promoted Flight Lieutenant and credited with a total of 38 victories, including 15 destroyed or captured. A bar to his DSC had been gazetted on 29 June, for ‘exceptional daring and skill in aerial fighting on many occasions’, and he received the French Croix de Guerre on 11 July, becoming – along with fellow Australian RNAS ace Roderic (Stan) Dallas – one of the first three British Empire pilots to be so decorated. In August he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for ‘exceptional skill and daring’, followed by a bar to the decoration in September for ‘remarkable courage and boldness in attacking enemy machines’. He was mentioned in despatches on 11 December, and promoted to Flight Commander the following month.

Eyewitness Accounts

The book Fighting Triplanes by Evan Sadingham contained several vivid descriptions and eyewitness accounts of Little’s extraordinary ability as a fighter pilot, including an interesting study written by Sir Geoffrey Bromet: Little’s tactics were unorthodox and startling in their audacity:…on 10th May Little again found himself outnumbered when he engaged five Albatros scouts…meanwhile Little was at it again, this time attacking three two-seaters…during July, Little was in good form; he was awarded the DSO immediately followed by a bar to it!

Despite Little’s prowess in combat, as an aviator he was said to be ordinary at best, enduring a number of crash-landings. What gave him his edge as a fighter pilot were his keen eyes, excellent marksmanship, and willingness to single-handedly take on entire enemy formations and close in on his prey before opening fire. Fellow No 8 Squadron member Reggie Soar recalled: Although not a polished pilot, he was one of the most aggressive… an outstanding shot with both revolver and rifle… while ace Robert Comptson described Little as: not so much a leader as a brilliant lone hand… small in stature, with face set grimly, he seemed the epitome of deadliness.

Many who knew him saw a sensitive side, however, Soar noting that Little was also a collector of wildflowers, and his wife contending that his appearance in photographs belied his sense of humour. Squadron Commander Raymond Collishaw, who would finish the war as the ‘top-scoring ace of the RNAS’, summed up Little as: an outstanding character, bold, aggressive and courageous, yet he was gentle and kindly. A resolute and brave man.

Following a period of rest in England, Little turned down a desk assignment and volunteered to return to action on the Western Front, joining Lieutenant Colonel Collishaw’s No 3 Squadron RNAS in March 1918. The unit evolved into No 203 Squadron of the new Royal Air Force on 1 April, formed after the merger of the RNAS and the Royal Flying Corps. Now promoted Captain and again flying Sopwith Camels, Little gained a further nine successes, beginning with a Fokker Triplane on 1 April , and concluding with two kills in one day on 22 May, an Albatros and a DFW

In one narrow escape his logbook records: … I was attacked by six other E.A. (enemy aircraft) which drove me down through the formation below me. I spun but had my controls shot away and my machine dived. At 100 ft from the ground it flattened out with a jerk, breaking the fuselage just behind my seat. I undid the belt and when the machine struck the ground I was thrown clear. The E.A. still fired at me while I was on the ground. I fired my revolver at one which came down to about 30 ft. They were driven off by rifle and machinegun fire from our troops.

One fateful flight

On 27 May, Little received reports of German Gotha bombers in the vicinity and took off on a moonlit evening to intercept the raiders. Little’s commander the Canadian Collishaw launched an investigation but it was never established whether the single bullet that hit Little came from a gunner in the Gotha or from the ground. In 1971 Air Vice Marshal Collishaw wrote an appreciation of Little which read in part: The German bombers were making a nuisance of themselves by night and Little was very keen to bring down a German Gotha. He and I often went up in the moonlight periods without seeing anything…I went on leave leaving Little in command…Little decided to resume his search for a Gotha…he left the ground at about 9 PM on 27 May 1918 in his Bentley-engined Camel. Early the next morning a message was received from the army that Little had been shot down dead near Norviz. I conducted a thorough investigation but nothing could be learned beyond the fact that Little’s aircraft had crashed after he was fatally wounded in the groin. Air historians have searched the German records fruitlessly to try to identify who fired the fatal shot. Little’s air fighting career was an inspiration to his contemporaries and a tribute to the high standards of Australian manhood.

There is no doubt that Little was one of the greatest Triplane exponents of the war. The London Times of 24 July 1918 revealed in an obituary that: Captain Alexander Little … held the record among pilots of the late RNAS for enemy machines destroyed. Little was buried in the village cemetery at Nœux, before his body was moved to Wavans British Cemetery in the Pas de Calais. Aged 22, he left a widow, Vera, and a son, Alec. In accordance with her husband’s wishes, Vera travelled to Australia to raise their son, who was born in March 1917. The propeller of Robert’s aeroplane was fitted with a clock and presented to Vera. She remarried in the 1920s, living until 1978 and surviving Alec by a year. The propeller blade from Little’s Sopwith Triplane presented to his widow eventually went on display at the Australian War Memorial, along with his awards and the wooden cross of his original burial place at Nœux.

The Sopwith Pup he flew with No 8 Squadron RNAS, N5182, was rebuilt to flying standard and in October 1976 led a flypast to commemorate the squadron’s Diamond Jubilee, before going on permanent display at the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon. One of the buildings of the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) in Canberra, opened in 1986, was named in Little’s honour.

How the Gladstone bag with its important contents came to be on a rubbish tip in a remote corner of Queensland remains a mystery. We are much in debt to the finder for his generosity in handing over the memorabilia to the Nowra Museum. And we hope any reader or museum visitor who can throw any more light on the memorabilia will let us know. By the way Texas, Queensland, got its name when landowners the McDougall brothers in 1840 engaged in a land dispute they thought similar to that earlier between Mexico and America over Texas USA.

Sopwith Shiners

In 1914 the Royal Naval Air Service had 91 heavier-than-air aircraft and eight lighter-than-air aircraft. By 31 March 1918 these figures had increased to 2,815 and 246 respectively. On 2 August 1917 Squadron Commander Dunning made the first deck landing on a British ship – the first ever to be made on a ship under way – when he flew a Sopwith Pup on to a foc’sle flight deck fitted to the battle cruiser HMS Furious, before it was fully converted to an aircraft carrier.

Several Australians served with the Royal Naval Air Service and enjoyed flying the Sopwith Triplane. The unorthodox arrangement of three staggered main-planes not only led to the nickname of ‘Tripehound’ or ‘Tripe’, it bestowed on the aircraft some excellent flying characteristics. In spite of its medium-powered Clerget rotary engine of 110 horsepower, the aircraft could out-climb its contemporaries and had a remarkable rate of roll. Later modifications introduced the 130 horsepower Clerget, and a smaller-type tailplane which improved the aircraft’s diving capability.

The Germans were very impressed, and surprised when they tested a Triplane which had been captured intact. Partly as a result, several different types of German and Austrian triplanes were produced, including the famous Fokker Dr I.

When the Sopwith Triplane was first wheeled out, with its simple interwing bracing, there was speculation that the design might be structurally weak. But Sopwith’s chief test pilot Harry Hawker had no such doubts and he confidently looped the prototype N.500 within minutes of taking off on the first test flight in May 1916. Fellow Australian Harry Busteed, as a squadron commander in the Royal Naval Air Service, also took part in the testing. On 22 September he flew the 130 horsepower second prototype N.504 over Hendon. The Triplane served with the Royal Naval Air Service until about February 1917, until they were replaced by the Sopwith Camel later in the year.

One Sopwith Triplane, N.5912, has been preserved and is on display in the RAF Museum, Henlow; another is in Russia. On the list of British aces of the 1914-18 War, two Australians – Little and Major Roderic Stanley Dallas from Mt Stanley in Queensland – occupy 8th and 16th positions. Both men achieved many of their victories with the Sopwith Triplane.