- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Maryborough

- Publication

- December 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

One of the most significant rescue operations of Australian military forces occurred after the Japanese had overrun Dutch colonial western Timor in 1942. At this time Timor, seen as a vital bastion to northern Australia, was defended by a hastily assembled combined garrison of Dutch, Australian and British forces. Following the surrender of the Allied force to numerically superior Japanese invaders a rearguard of 33 Australian servicemen, mainly RAAF, made their escape and this is their story.

To the indigenous people and to Dutch and Portuguese colonials, Timor was home. To the overall Netherlands East Indies (NEI) it was an important defensive outpost. To Australians and the Japanese, it was a critical staging post to northern Australia.

At 31,270 km² the island of Timor is about half the size of Tasmania and at the closest point is 700 km (440 miles) north of Darwin. Only nine degrees south of the Equator, it has a hot tropical climate with a monsoon rainy season from December to March. It is ringed by coral reefs with a narrow strip of fertile land before jungle takes over, extending to rugged mountains; transport is difficult as there are few roads. Timor was politically divided almost equally in two with the eastern portion being colonised by the Portuguese and the western portion by the Dutch.

Sparrow Force

In December 1941 concerns about a Japanese invasion caused the Dutch colonial power to request the aid of Australian forces to help defend the islands of Ambon, Buru and Timor, all having vital airstrips leading directly to Australia. Sparrow Force, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Leggatt, was mainly drawn from the 2/40th Infantry Battalion (766 men) which had been formed in Tasmania, and the 2/2nd Independent Company (268 men), recruited mostly in Western Australia, plus 2/1 Heavy Battery (126 men) and other supporting elements. The combined force of 1,402 troops departed from Darwin on 10 December 1941 in the troopship Zealandia escorted by the armed merchant cruiser HMAS Westralia. They reached Kupang on 12 December where they joined the local garrison of 600 Dutch troops, which included about 200 locally enlisted militia, under the overall command of Lieutenant Colonel Nico van Straten.

Most of Sparrow Force was involved in the defence of Penfui Airfield on the outskirts of Kupang, the capital of Netherlands Timor. The Dutch had already installed two ancient 6-inch coastal guns which had been retired from HMS Hibernia with pedestal mounts from HMAS Sydney (1), which were emplaced to deny the Japanese naval bombardment of the Penfui airstrip. These guns were of minimal value and, because of their limited elevation, useless against aircraft.

A few days after arrival the 2/2nd Independent Company, a commando unit, was joined by locally enlisted men and some Europeans. They embarked in the Dutch training cruiser Soerabaja and made for Dili, the capital of nominally neutral Portuguese Timor, to prevent a Japanese landing. The Portuguese had an armed force of only 150 men in their colony. Reinforcements were on their way from Portuguese East Africa but the Japanese invasion occurred before they arrived.

Since the days of Dampier, Bligh and Flinders Kupang had been known to early Australian explorers as a center for fragrant sandalwood and trepang, the latter sourced from northern Australia. Kupang was a small but pleasant sleepy colonial town situated at the head of a fine but shallow harbour. With the arrival of Sparrow Force, it took on a new lease of life with cafes, restaurants and brothels springing up almost overnight.

American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command

In a desperate effort to coordinate defences against a Japanese onslaught a short-lived supreme command of all Allied forces in South East Asia was formed on 28 December 1941 under the command of General Sir Archibald Wavell. Wavell told these forces that air operations were the governing factor in the enemy’s advances and were likely to be of the greatest importance to both sides. This led to more strenuous efforts being made to improve facilities at Timor’s Penfui airfield. But shortly after the fall of Singapore (15 February 1942) the ill-fated ABDA crumbled and by the end of the month General Wavell had departed and ABDA ceased to exist.

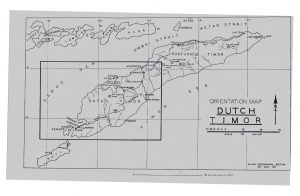

Wartime map of Timor

After dark on 15 February a convoy slipped out of Darwin comprising four transports, the American ships Meigs, Mauna Loa and Portmar and the Australian island trader Tulagi, carrying the Australian 2/4th Pioneer Battalion and a battalion of the 148th United States Field Artillery Regiment plus their supplies. They were escorted by the cruiser USS Houston, the destroyer USS Peary and the sloops HMA Ships Swan and Warrego. Next day they were sighted and shadowed by an enemy seaplane and on the morning of 17 February another seaplane took over shadowing duties. Two Kittyhawks were sent from Darwin to take care of the shadowers but one never returned and the other failed to locate the convoy. Then came an intense enemy air attack on the convoy by bombers and seaplanes. In spite of determined attacks only one ship suffered slight damage with two casualties. The immunity of the convoy was largely due to the accurate and intense anti-aircraft fire which kept the aircraft at high altitude.

ABDA, now convinced that an invasion of Timor was imminent and the Houston convoy would be meeting both naval and air attacks, considered the risk unacceptable and ordered that they return to Darwin without landing. While the defenders soon realized that any further reinforcements were unlikely, surprisingly one group arrived. On 9 February anti-aircraft guns and their crews had been dispatched from Batavia in SS Ban Hong Liong, escorted by USS destroyers Aldenand Edsall and they reached Kupang on 16 February. So Sparrow Force was reinforced by 189 British anti-aircraft gunners from a Territorial Unit, the 79th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery. While disembarking they were attacked by Japanese aircraft but managed to get their men and equipment ashore.

No. 2 and No. 13 Squadrons RAAF

No. 2 Squadron RAAF, recently equipped with American Lockheed Hudson bombers, was under the command of Wing Commander Frank Headlam. On 6 December 1941 the first flight of four aircraft relocated from Darwin to Kupang and on 12 December another flight of eight aircraft reached Kupang. Later some aircraft were repositioned at Dili.

No. 13 Squadron, under the command of Squadron Leader Peter Ryland, was also equipped with Hudsons. At the end of December, they had positioned two flights a further 700 km north to the airfield at Laha on Ambon and another flight of four aircraft to a new base at Namlea on the island of Buru to the west of Ambon.

Both Hudson squadrons undertook reconnaissance flights and brought in supplies from Darwin. Then on 12 January 1942 five Hudsons attacked Japanese shipping but they were intercepted by fighter aircraft and four Hudsons were destroyed, with 16 aircrew missing, assumed dead. A few days later another heavily laden Hudson stalled on takeoff and plunged into the ground where it exploded, killing all eleven passengers and crew. The strength of the squadron had suddenly sunk from 14 to 9 operational aircraft.

The first Japanese air raid against Penfui occurred on 26 January when seven Zeros strafed the base, and two Dutch, one American and one British aircraft were destroyed. Again on 30 January (when the Japanese invaded Ambon) enemy fighters raided Penfui, destroying another Hudson that was taxiing on the runway. Off the coast a Qantas flying-boat en route from Darwin to Koepang and thence Surabaya to evacuate women and children was shot down. Amongst the passengers were two RANR Lieutenants, David McCullock and Bruce Westbrook, who were on their way to join the staff of Commodore John Collins RAN1 in Batavia. Fifteen passengers and crew including McCullock were killed, the remaining five, including Westbrook, swam three miles to shore. Despite the intensity of air raids on Kupang the enemy resisted bombing the aerodrome and damage was comparatively slight with no RAAF causalities on the ground.

As a precaution the Hudsons were moved to an emergency strip about 40 miles to the east near the Mina River where they were camouflaged against a jungle backdrop. On 27 January, in a planned buildup of fuel supplies at Mina River, the US destroyer Peary offloaded a consignment of fuel drums. Sixteen seamen then swam with the drums lashed together to form a raft but they were carried five miles up the coast by the current. After two weeks of intensive labour by a RAAF shore party cutting a path through swamps and jungle the fuel was eventually delivered. Meanwhile a Hudson which had flown the shore party from Penfui to Mina was attacked and destroyed on the ground.

The Americans now tried to provide some fighter aircraft to help in the desperate defence of Java. On 11 February nine new Kittyhawk fighters flew from Darwin to Java, guided by a Beechcraft with a RAAF pilot. The fighters lost the Beechcraft in cloud and couldn’t find their refueling stop at Penfui and as a result all nine crashed in Timor.

With increased attacks on Namlea the base was evacuated at the end of the month. No. 2 and No. 13 Squadrons maintained regular reconnaissance patrols, but as Penfui was only safe at night one crew would take off from Penfui at dawn, complete their patrol and head for Darwin; reversing the procedure, another crew flew from Darwin, covered the patrol, and landed at Penfui at dusk. On 14 February a Hudson from 13 Squadron taking off from Penfui at dawn was struck by lightning and crashed, the pilots Flight Lieutenant Harold Cook and Pilot Officer Viv. Leithhead survived and as a matter of expediency joined up with their colleagues in No. 2 Squadron. These two would later be attached to the Bryan Rofe rearguard party.

On 18 February, following another heavy air raid, there was a reconnaissance report of an enemy convoy steering towards Timor. A decision was then made by the ABDA Command to pull the RAAF out of Timor and return to Darwin, and the obsolete training cruiser HNLMS Soerabaja was ordered from Kupang to the relative safety of her namesake home port in Java. At dusk on 18 February six Hudsons arrived to take RAAF support personnel to Darwin. On their way an enemy submarine was sighted; since they carried no bombs, they dived low and fired their guns but without success.

The volunteer rearguard party of about 30 men was left behind to destroy equipment and airport facilities lest these fall into enemy hands. Two Hudsons were sent to collect this rearguard on 20 February but finding that the Japanese had already invaded they returned empty handed.

Flight Lieutenant Bryan Rofe RAAF

Early in the war it was recognized that meteorological officers were required to assist in accurate weather forecasting and to improve the science of artillery and maritime and aircraft navigation. A recruitment campaign was instituted to attract smart young men with suitable scientific backgrounds. Selected candidates would be given a crash course which condensed most of a three-year degree into six months of intensive training followed up by a further period of field training before graduates became commissioned officers in the RAAF. Science teachers filled most of the 22 places on the initial course including the youngest member, a 22-year-old from South Australia, Bryan Rofe.

On 17 April 1941 Bryan was commissioned as a Flying Officer and posted to RAAF Pearce in Western Australia, and in September, posted to Darwin for duties with a Hudson Squadron. On the morning of 30 September Bryan was at the docks as part of a newly formed Installations Team, which took off in an ex-Qantas Empire Flying Boat for Kupang Bay.

They arrived on one of the Southwest Pacific’s tropical islands, without a care in the world. Initially there were plentiful supplies of local produce, with Dutch beer and American cigarettes, not to mention a number of beautiful olive-skinned maidens. They quickly established themselves at ‘Australia House’.

The Installation Team mostly comprised those who in civilian life had been mechanics, carpenters or radio technicians. None seemed to have any serious expectations of advancement in military service. They were here to work under Dutch supervision with hundreds of locals, involved in extending runways, building communications towers, accommodation barracks, installing diesel generators and fuel supplies. The Installation Team had to ensure that all this worked, especially the radio and direction finding equipment. All had to be in place before the onset of the wet season just three months away.

Bryan Rofe, a weatherman – a mere Met Officer – soon found his responsibilities growing as others began to appreciate his management skills. With no medic on staff but with increasing numbers (up to 30%) going down with various tropical complaints Bryan sought advice from Dr Gabeler who ran a hospice on the outskirts of town. The doctor taught him how to treat patients suffering from dysentery, dengue fever, jungle rot and malaria. Working with the doctor, by the year’s end Bryan was basically conversing in the local language. In exchange Bryan delivered medical supplies to the hospice. He received his promotion to Flight Lieutenant on New Year’s Day 1942.

Paymaster Lieutenant Alan Bridge RANVR

Alan Bridge, a 31-year-old barrister and married man from Sydney, enlisted in the RANVR on 10 January 1941 as a Probationary Sub Lieutenant. He did the usual short officer training courses at HMAS Cerberus and was promoted Lieutenant on 24 April 1941. He was then posted to Navy Office for intelligence duties and thence on 5 January 1942 to HMAS Melville additional for intelligence and staff duties at Kupang.

As far as can be determined, he had little or no sea training or knowledge of naval operations when he arrived in Batavia (Jakarta), first taking up an appointment with the newly minted ABDA who

were first housed in Batavia before relocating to a luxury hotel complex near the Dutch administrative center of Bandoeng. In the mountains the air was cool and bracing and the risk of bombing was less acute. From here he had written lightheartedly to his Sydney law school mentioning: ‘becoming quite expert in diving into appropriate cover from bombs dropped in regular Japanese visits, but hosts of native servants spoilt us utterly so Japs, mosquitoes, scorpions and other attentive friends did not detract from the charms of life’.

On 28 January 1942 Lieutenant Bridge, found himself RAN Liaison Officer at Kupang. In this remote outpost life continued to be pleasant until the Japanese invasion. With the rush to withdraw non-essential personnel from the island, somehow Alan Bridge failed to make the rendezvous with an evacuation ship and was left behind. This sole representative of the Australian Navy, unarmed and resplendent in a white tropical uniform, then joined up with the RAAF rearguard who were armed and in more war-like attire. Alan’s white shoes did not last well and after a few days he went barefoot. When a soldier later died Alan was donated a pair of boots. His Navy cap was soon discarded for a more robust tin hat which could double as a water bowl.

Alan Bridge did not fit into this new unit well and was regarded as something of a passenger. However, from his previous duties he knew that USN submarines were transiting these waters on patrols between their new Fremantle base and the South China Sea. He initiated a life-saving option when he suggested that they ask Darwin if an American submarine returning from patrol could make a rendezvous on the Timorese north coast. While the team was at first not receptive to this idea it eventually gained acceptance as possibly their only hope of salvation.

Steven Farram (2000) says Alan Bridge found the Timorese were 100% anti-Japanese and that this view was shared by other members of the escape party, noting the locals were helpful to the Australians and hated the Japanese, not the least because they ill-treated their women.

The Alan Bridge Narrative – staying one step ahead of the enemy

Alan Bridge’s son Campbell Bridge2 says his father spoke little of his wartime experiences but had written a censored letter which appeared in Alma Mater, the magazine of his old school, St Ignatius, at Riverview in Sydney. Thanks to the school archivist we were able to track this down and the following summarises the narrative.

For some weeks before invasion, Japanese air visits had taught us that the local insect swarms were not the only neighbours who could fly freely and bite hard. Then, one evening, just after sunset, a normally peaceful time which a Dutch officer and I usually devoted to mutual language instruction, the island was set astir by news of two large approaching convoys. After hurried consultations, all Allied troops were rushed to battle positions. Before midnight, the Japanese were detonating naval shells on our town.

Before dawn, public buildings, service quarters and civilian houses were for the most part set ablaze or blown up to render them useless to the enemy who had landed in force at five scattered points. By sunrise, reconnaissance and bombing aircraft as well as artillery fire were unpleasantly frequent, close and potent. While the morning was still young fresh waves of planes came overhead, this time dropping paratroopers by the hundred, each wave being accompanied by other aircraft heavily bombing and strafing the small ground defences.

As the paratroop tactics continued, other ground troops infiltrated wherever their green uniforms found natural cover – in tree tops, into cornfields, behind shrubs and under bushes. While Allied forces resisted, but without aircraft and blockaded against reinforcements and constantly facing numbers and material overwhelmingly greater than their own, they could do no more than delay the invaders.

After the fall of the last defended post, the majority of Allied servicemen were prisoners but many escaped and were at large. In the ensuing weeks Japanese patrols rounded up most of these fugitives, but a party of about 30 Australians, in which I finished up, had the good fortune to remain free. Our party was a mixed bag mainly from non-service backgrounds ranging from 19 to 42 in age. We began our two months together with the clothes in which we stood, we also had a few rifles and ammunition, one axe, some knives, tobacco and matches but most importantly a portable radio plus batteries with which we could contact Darwin.

Foraging for food and staying one step ahead of enemy patrols became the mainstay of our existence. We would dive for cover as searching aircraft passed overhead but thanks to faithful natives we managed to remain clear of enemy foot patrols. Malaria affected us all and with physical weakness we became susceptible to other illness from which four men died. We were forever hungry, having to survive on rice and a limited supply of vegetables and the very occasional luxury of a chicken or goat meat. Our rescue came in the nick of time as we were at a low ebb, food was short, our radio batteries were just about finished and Jap patrols were getting very close. (Alan then concludes by giving credit to the courage of their local hosts and the American submarine crew in making good their escape.)

The Invasion

The invasion of Timor was directly associated with an overall offensive campaign including the bombing of Darwin which first occurred at dawn on 19 February 1942 and largely cleared the skies of Allied aircraft. The first shore bombardment of Kupang began in the early morning mist of 20 February 1942 and intensified as the cruiser IJNS Jintsu,flying the flag of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, joined with three destroyers in pounding the town and setting buildings alight. This was followed up by strafing and bombing raids; noticeably the airfield was not bombed, being intended for Japanese use. After the bombardment troops were offloaded from nine transport vessels to secure the town.

Regrettably with no Allied air or naval defences the landing was unopposed. Now ashore were two battalions from the 228th Regiment of about 4,000 men with five small tanks. Their advance had the unfortunate consequence of separating Dutch and Australian forces.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF) used to spearhead invasions were a volunteer battalion of two 750-strong paratroop units. As the pride of the Japanese military they became known as the ‘Sons of Heaven in the Sky’. On 20 February the RAAF rearguard party witnessed over 300 ‘Sons of Heaven’ conduct precision drop landings north of Penfui. The Japanese paratroopers were from the 3rd Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force under the command of Lieutenant Commander Koichi Fulumi. Limited to 11 paratroopers, plus supplies, per aircraft, this was a large undertaking with about 30 aircraft being involved in the initial drop.

Once on the ground the paratroopers lost no time in regaining their supplies and forming up ready for action. These were far from the stereotyped ‘Little Yellow Men’, they were taller than average, of good physique and obviously well trained – if anything, more like Samurai warriors.

The rough terrain had meant that the drop zone was some hours from their intended objective which was to capture the airfield intact. This gave defenders ample time to prepare and when the fierce battle was over only 78 paratroopers were alive. But the next day they were reinforced by a second wave of a further 185 paratroopers and when they linked up with Japanese ground forces they outnumbered the defenders who, running low on ammunition, were obliged to surrender on 23 February 1942.

The ground forces including the anti-aircraft battery of 8 x 40 mm Bofors put up considerable resistance and 14 kills were claimed on enemy aircraft including two carrying paratroopers with subsequent loss of their troops. Sparrow Force lost 92 killed but many more died when prisoners of war. Some troops escaped to the hills, where they died, and others were captured, but a few eventually joined their comrades in Dili.

The Escape

Before leaving Timor Wing Commander Headlam took a risk but made a wise decision when he appointed one of his younger officers, not from a service background, as leader of the rearguard. Bryan Rofe had demonstrated that he was a sound manager and one who commanded respect. This was an onerous task involving life and death decisions. From his training with Dr Gabeler the young RAAF officer also knew that disease was endemic and the importance of keeping the group together for survivability so the fit could nurture the sick until they recovered.

The rearguard party now had the choice of surrender or make for the coast and with the aid of the radio they had retained make contact with Darwin calling for a seaplane rescue mission. These were not hardened warriors taught to withstand the shock of battle, but mostly ordinary men who a few months earlier had been local tradesmen. Importantly for their survival they were men with practical skills who were resourceful and knew the value of improvisation.

Being almost all from the RAAF they pinned their hopes on being rescued by a seaplane with the commandeered Qantas Empire flying boats being the only ones big enough to carry such a large party. Japanese bombing of Broome had destroyed the flying boats where they were moored and put paid to this option. They then suggested a Hudson might land on a beach which they had surveyed but this was unacceptable to RAAF authorities.

With the aid of locals, who still accepted payment in Dutch guilders, this rearguard group slowly made their way to the north coast and evaded capture for 58 days whilst being pursued by Japanese ground and air units. The loyalty of the Timorese cannot be praised highly enough in looking after the Australians as without them survival would have been impossible. A far easier option for the Timorese would have been betraying the escapees to the Japanese and claiming a reward.

The region was rugged country with few tracks and they had to proceed over mountains with freezing night-time temperatures, hack through jungle, ford crocodile infested rivers, steer clear of buffalo wallows and the inevitable swarms of dawn and dusk mosquitos. With their provisions soon exhausted they had to rely on what they could secure from friendly natives or live off the land. The group suffered from multiple illnesses and four died, including one from a snakebite. The following were laid to rest in Timor: Flying Officer Thompson, Corporal Andrews, Aircraftman Class 1 Graham, all of the RAAF, and Private C. Clements from the AIF (a radio operator attached to No. 2 Squadron).

Eventually Australian and American authorities were convinced of the feasibility of the Alan Bridge suggestion of submarine rescue and a plan was put in place for USS Searaven to attempt taking off the survivors. With Japanese air and sea patrols, a daytime rescue was impracticable so a signaling system was arranged for a nighttime rendezvous.

Twice Searaven approached the shore and launched its 18-foot wherry, a portable boat complete with motor (which did not work). The oars were missing, so improvised oars were made from packing case slats. To take the wherry inshore through surf and bring sick passengers back onboard required strong swimmers, Ensign George Cook was a volunteer together with two others, Petty Officers Joseph McGrievy and Leonard Markeson. Cook swam ashore twice but found no survivors.

On Thursday 16 April Bryan received a letter via a native courier from the local Rajah advising that the war between the Dutch, Australia and Japan was over as all Allied Forces in the Netherlands East Indies had surrendered. Dutch authority did not readily extend into remote villages who still respected their hereditary Rajah. In appealing to the Australians the Rajah was possibly thinking of their welfare and that of his subjects as Japanese reprisals for those helping the enemy were brutal and many Timorese died. This also advised Bryan that his present position had been reported and that his party would be caught if he continued to defy Japanese authorities. The courier told Bryan that 300 soldiers had been dispatched to find them and they would arrive at dawn on 19 April.

On a radio that was now running on dangerously low batteries, one last attempt was made to contact Darwin for a further rescue mission that night. And so it was that Ensign George Cook USN staggered ashore with a torch in one hand and a pistol in the other. Shining his torch, he found a disheveled person wearing what had once resembled navy whites, with Army boots and a tin hat – he had found Lieutenant Alan Bridge RANVR. Shortly after this he was united with the rest of the party. It had been decided that the fittest men would go first, but owing to the time taken in getting them to the submarine a second group could not be taken that night.

Those remaining had to bunker down for another night and hope the submarine returned and in the meantime that they would not be discovered by a Japanese patrol. They need not have worried as at the appointed hour Searaven returned and the reliable Ensign Cook came ashore. This time it was more difficult as the sick survivors, who could barely swim, needed help in getting through surf and on to the wherry, some would not have survived but for the strength of the American petty officers. Getting them into the submarine was also tortuous but eventually all was accomplished and after 58 days on the run they were on their way back home.

USS Searaven – SS-196

USS Searaven, a Sargo-class diesel-electric submarine, was commissioned in October 1939. Her early wartime service was operations in Philippine waters. On her third patrol, under command of Lieutenant Commander Hiram Cassedy, she was directed to make for the Timorese coast and undertake the immensely difficult and dangerous task of locating and rescuing the Australian rearguard party from behind enemy lines. With a complement of 59 officers and men Searavenhad the challenge of finding space for another 33 men, most in very poor condition and needing bunks. In immensely challenging conditions this rescue mission was successfully accomplished over two days on the evenings of 17 and 18 April 1942.

Five days later an electrical fire broke out in Searaven’s engine room which immobilised the heavily loaded boat. After a three-hour battle to control the fire Searaven continued on the surface but, reduced to using batteries, only making two knots of headway. Luckily another submarine, USS Snapper, was in the area and was able to take the stricken boat in tow. In choppy seas Searaven gyrated like a fairground ride making all aboard violently sick. By late afternoon more help was at hand with the US destroyers Paul Jones and Parrott and the corvette HMAS Maryborough standing by. Maryboroughtook over towing duties and the convoy of three surface ships and two submarines made the safety of Fremantle on Anzac Day, 25 April 1942. Here the Timor evacuees were taken for hospitalization in Perth. They were an unforgettable sight on arrival; emaciated, many unable to stand and barely alive.

Recovery, both physical and emotional, took time but most were out of hospital within a month and back with their families. Many later went on to complete military service in the Pacific. However, few fully recovered from the Timor ordeal with recurring attacks of malaria plaguing them.

Awards

For their conspicuous service in the rescue mission of Australian survivors off the coast of Timor the following received recognition: Flight Lieutenant Bryan Rofe, and his second in command Flying Officer Arthur Cole, received the MBE and Corporal Leslie Borgelt the BEM. American Petty Officers Joseph McGrievy and Leonard Markeson received the Silver Star and Ensign George Cook and Lieutenant Commander Hiram Cassedy the Navy Cross.

Life after Timor

Lieutenant Bridge, thoroughly debilitated, obtained a medical discharge from the RAN on 27 August 1942. His life spiraled into depression when his young wife suddenly died leaving him with an infant daughter and son. With an inner strength he gradually recovered and returned to working part-time in the legal profession. He later remarried and had another son. Alan Bridge became a Queen’s Counsel and was elevated to the bench of the Northern Territory Supreme Court. The Honourable Mr Justice Bridge died prematurely in 1966 while still in office, aged 58.

Eight weeks after Searaven arrived at Fremantle the newly promoted Squadron Leader Bryan Rofe married Patricia, his sweetheart from Adelaide Teachers’ College. They had a daughter and through her a grandson Tom Trumble3 who wrote of his grandfather’s wartime experiences. After war service Bryan returned to the Bureau of Meteorology before joining the fledgling Long Range Weapons Establishment in South Australia. His final career change was to the prestigious position of Director of the Australian Antarctic Division based in Melbourne. Bryan Rofe passed away at his home in Melbourne on 27 August 1971, dying of cancer at only 53 years of age.

While this records the exploits of a number of brave servicemen and those who supported them, what about an equally brave ship which made all this possible, USS Searaven?

In 1946 Searaven was one of eight submarines in a total fleet of 95 vessels used as targets in the atomic tests, Operation Crossroads, at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The purpose of these tests was to investigate the effects of nuclear weapons on warships using one air dropped bomb and one bomb detonated underwater. While some ships sank and others were severely damaged Searaven escaped with negligible damage. Searaven, the grand old survivor, was decommissioned on 11 December 1946 and finally she was sunk as a target on 11 September 1948.

Summary

This is a story of heroic bravery set in a maritime environment with major players coming from the RAAF and the USN. For this reason, it may not readily fit into naval history. This is a pity as there is plenty to recommend it in our understanding of the Timor campaign. It provides an insight into the life of one lonely naval officer, who made a difference, which helped save the lives of his comrades.

This narrative also demonstrates three elements of human endeavor which can reach great heights under exceptional leadership. Firstly, the fortitude and courage of a group of ill-prepared Australian servicemen, who against all odds, chose the immense difficulties of escape when surrender would have been a more practicable option. Secondly, the outstanding help and assistance given to the Australians by materially poor, but morally rich, Timorese people who endured further hardship in providing guidance, food and shelter for the escapees. In so doing they were in danger of brutal reprisals and placed their lives at risk. Finally, the determination of a fine band of American submariners who in the most demanding of conditions tried, and tried, and tried again, until they succeeded in finding the elusive fugitives and brought them to safety.

Notes

- After the fall of Singapore CDRE John Collins RAN was appointed to ABDA as Commodore Far East Squadron, comprising RN and RAN ships, based at Batavia.

- 2. Alan Bridge’s son by his second marriage was also named Alan, but to avoid confusion is known by his middle name, as Campbell Bridge. Campbell followed his father into the legal profession; he is now a Senior Counsel and practises in Sydney.

- Tom Trumble was born after his grandfather’s death but later inherited a vast amount of letters written between his grandparents covering their wartime separation. Tom Trumble, a Melbourne based journalist, used these letters as the basis for his book Rescue at 2100 Hours.

References

Bridge, Alan, Bruce, Keith Ian, One Step Ahead of the Japs, Alma Mater School Magazine – 1942 edition, Saint Ignatius College, Riverview, Sydney.

Cuneen, Tony, Bar History – Doing their Bit: Barristers in the Second World War, Bar News – Summer 2011-2012, NSW Bar Association.

Donaldson, Graham, The Japanese paratroopers in the Dutch East Indies 1941-1942, https://web.archive.org/web/20150708104829/ http://www.dutcheastindies.webs.com/japan_paratroop.html

Farram, Steven G., From Timor Koepang to Timor NTT: A Political History of West Timor 1901-1967, Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Charles Darwin University, 2000.

Gill, G. Hermon, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, Vol I, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957.

Gillison, Douglas, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942, Vol I, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1962.

Gregory, Mackenzie J., A History of Submarine USS Searaven who rescued 33 RAAF personnel from enemy held Timor in 1942, Ahoy–Mac’s Web Log, 29 July 2007.

Joyce, J., The Story of the RAAF Meteorological Service, Metarch Papers No 5, October 1993, Bureau of Meteorology.

Macdougall, Tony, Collins of the Sydney, Clarion Editions, Mudgee NSW, 2019.

McLachlan, Grant, Sparrow: A Chronicle of Defiance, Klant, Havelock North, NZ, 2014.

Mildren, Dean, Big Boss Fella All Same Judge: A History of the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory, The Federation Press, Sydney, 2011.

Trumble, Tom, Rescue at 2100 Hours- The Untold Story of the Most Daring Escape of the Pacific War, Penguin, Melbourne, 2013.

The Japanese Invasion of Dutch West Timor Island February 1942, https://dutcheastindies.webs.com/SNLF.html