- Author

- Wright, Ken

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Ken Wright

This article covering the exploits of Commander Norman Holbrook, VC, RN, is a timely reminder of these events which occurred a century ago. Surprisingly, looking through back copies of this magazine, there has been very little devoted to this exceptional submariner other than a short article in March 1996 and ten years later in March 2006 another article (Submarine in the Bush) relating to the establishment of submarine memorial at Holbrook. We trust this helps to redress the balance.

In the wake of the 28 June 1914 assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, the Duchess of Hohenberg, by a young Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, the madness of war enveloped many countries in Europe and for one reason or another they declared war on each other. August was a particularly busy month for war fever as Germany declared war on Russia and France, Russia on Germany then Great Britain on Germany. Just to complicate things even more, because of her alliance with Great Britain Japan also went to war against Germany.

Initially, Turkey (Ottoman Empire) remained neutral but when Britain seized two warships that were being built in England for the Turkish Navy and which had been paid for, Germany stepped in and donated two of their warships; the battle cruiser SMS Goeben and the light cruiser SMS Breslau. In October 1914, Turkey closed the Dardanelles to Allied shipping and supported Germany against Russia. Having strategic interests in the Dardanelle Straits and an alliance with Russia, Britain and France had no choice but to go to war against Turkey on 5 November.

The Dardanelles

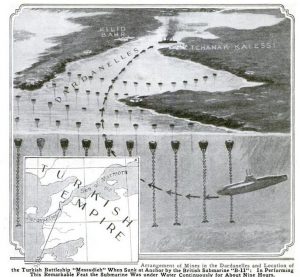

The sixty-six kilometre long Dardanelles Straits is a narrow strait in north-western Turkey that links the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. Known in ancient times as the Hellespont, the strait is only six kilometres across at its widest point with depths varying to a maximum of eighty metres with the water flowing in both directions. From its mouth at Cape Hellas to the Sea of Marmara, the narrow waterway is bounded by the Gallipoli heights and by many lesser hills. The entrance to the straits was guarded by four forts, two on either side. Seventeen kilometres up the straits was another series of forts and a single line of sea mines strung from shore to shore. At the Narrows, just twenty two kilometres from the entrance, the channel has a width of less than 1,463 metres and is protected by more forts.1

Three days after Britain declared war on Turkey, British and French ships shelled the Dardanelles’ outermost forts and after a twenty minute bombardment and two lucky hits, the forts of Kum Kale and Seddülbahir were put out of action. This in turn gave the Allies a false sense of their ability to destroy all the forts and all but advertised that they might be planning, at some point soon, to sail up the strait and perhaps attack the capital city Istanbul (Constantinople). Turkey naturally began strengthening their defences including onshore fixed torpedo tubes, the placement of an assortment of artillery pieces of varying calibres and increasing the sea mine field.

In 1914, sea mines were usually either spherical or egg-shaped and had the detonators, or horns, mounted near the top of the mine. They were relatively cheap and simple to produce and as a weapon, very effective. A typical sea mine consisted of a concrete or stone weight and a length of cable attached to the mine with a percentage of the weight and size of the mine devoted to maintaining its buoyancy. Moored mines contained smaller explosive charges than land mines and could be tethered at various water depths. A ship or a submarine only had to touch one of the horns to cause detonation. In the case of a submarine, the diving planes or any other protrusion might simply snag the cable and the submarine’s movement would drag the mine down enabling one of the horns to make contact with the hull.

When war was declared against Turkey the submarine B-11, which was one of the oldest classes of British submarines, was ordered to the Mediterranean and based at Malta. In December 1914 she was ordered forward to the Dardanelles. The B class submarines were primitive and difficult to handle when submerged. In addition, fumes from their petrol motors often caused symptoms similar to drunkenness to the small crew, all of who had to sleep among the pumps and motors of the cramped interior.2 The battery power was limited and required constant resurfacing to recharge, which in theory precluded the B class making it under the minefields of the Narrows into the Sea of Marmara. These considerations aside, both the French and British submariners longed to get into the strait and do something positive rather than spending their time on tedious patrols of the entrance.

Twenty–six year old Lieutenant Norman Douglas Holbrook, RN in command of B‑11 was ordered to attack Turkish shipping at Cannakale. Lt. Holbrook may have thought it was action at last, but it could be viewed as a suicide mission considering the strength of the Turkish defences and in particular, the sea mine field, a formidable obstacle plus the fact that the B-11 was already well past her prime. In recognition that the undertaking was perilous each man in the crew (2 officers and 14 men) left a farewell letter to his friends, to be posted if the writer failed to return.

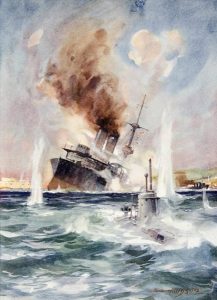

To achieve his objective, he would have to take B-11 under the minefield from Kephez Point and surface at Cannakale. Equipped with improvised mine guards on the fore and aft hydroplanes and a jumping wire from lessons learned from actions of the North Sea, B-11 set off at 0300 on 13 December.3 At 0415, the Turkish search-lights switched off just as they did each morning just before dawn. Holbrook crept along the coast at the mouth of the strait on the surface. When he began to submerge, there were vibrations coming from outside the submarine. On inspection, it was found part of the improvised mine guard around the forward hydroplanes had come loose and had to be jettisoned. Crew members jumped into the water and struggled to unscrew the guard as dawn was breaking. Holbrook watched from the tiny conning tower and worried. Would they be spotted in the growing light and fired upon? Without the guard, there was the risk the hydroplanes could hook a mine cable and drag a mine down for contact with the hull. Nevertheless, Holbrook decided to take the risk. Moving up the strait, Holbrook had to surface every forty-five minutes to fix his position. At 0830, nearing Kephez Point, he took the B-11 down to twenty-four metres and spent the next four hours feeling his way under the minefield. The submarine was, unknown to the crew, swept along by the deeper inward flowing current because when Holbrook surfaced to take his next periscope sighting, he was surprised to find himself off Cannakale and about 1.5 km away from the old Turkish battleship Messudiyeh at anchor in Sari Siglar Bay on the inside of the mine field.

From a letter to his parents dated 14 December, Holbrook wrote in part: ‘After five hours, I sighted a large warship on my starboard beam so altered course straight through the mine field for her and fired one torpedo at her when 1000 yards off. I heard an explosion and came up and she opened fire on me with every available gun, so I went down again and at the same time, my compass chucked its hand so all I knew I was in the middle of the mine field. Hadn’t the faintest notion of what direction I was pointing.’4

At the same time the torpedo was heading towards its target, the American Vice-Consul at Cannakale, Mr Cornelius Van H. Engert, was enjoying the winter sunshine in a rowboat in a peaceful spot just up from the great fortress of Killitbahir whose guns guarded the Narrows on the Gallipoli side of the strait. Suddenly, a huge explosion occurred. He looked down the straits and witnessed the last moments of the Messudiyeh. The ship was enveloped in a great cloud of smoke and shells from its guns were landing in calm water between it and Kepez Point as if the gunners were trying to hit some object. The battleship began to sink by the stern then keeled completely upside down in the shallow water. Members of the crew were seen scrambling all over the upturned hull. Fortunately, rescue efforts began very soon after but Turkish casualties amounted to ten officers and 25 crew. Meanwhile, B-11, swept by the currents, ran aground.

Holbrook: ‘Suddenly I hit bottom some [or something] hard at 40 feet which brought me up 10 feet so I came up to have a look around and saw the cruiser apparently settling by the stern, judged as best I could the way out, all I could see was land all round me and went down again and continued to hit the bottom for ten minutes when luckily I got into deep water. I had to come up twice more in the mine field to find out where I was and each time I was practically running ashore, but finally managed to get the boat more or less pointing for the open [entrance], the man at the wheel steering by a dirty mark on the compass which was all he could see.’

Holbrook now desperately needed a compass fix to plot his course for the open mouth of the strait to make his escape but without a compass, Holbrook was forced to surface and take sightings. Fortunately, he saw the entrance but without the compass, he still had to dive and surface to check his position as the submarine moved down through the minefield.

‘They sent a TB [torpedo boat] to chase me, luckily I never saw her as I only came up twice more during the last ten miles. I put in nine hours under water all told which I think is a record for a B class boat.’ After two hours of bobbing through the minefield and sneaking under the Turkish guns, B-11 surfaced at 1410 just off the Dardanelles entrance near Cape Hellas only to find herself near a British destroyer. They were home free. When the hatch was opened, a poisonous cloud of greenish-yellow gas issued from the submarine and it took thirty minutes before sufficient clean air had entered before the 600 hp petrol engine would start.

A Hero’s Welcome

Holbrook instantly became one of the early heroes of the war and in late December 1914 was the first submariner to be gazetted for the Victoria Cross. B-11’s First Lieutenant, Sydney Winn, was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and all other members of the crew received the Distinguished Service Medal. In addition to Holbrook’s VC, he was awarded the French Insignia of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. Even the enemy praised him. In his report to his government on the sinking, the American Vice-Consul Van Engert quoted the German Vice Admiral Johannes Merten who was in charge of the Dardanelle defences as saying in effect that the sinking of the Messudiyeh had been: ‘brilliant, daring and a mighty clever piece of work.’

During the time of the Dardanelles campaign, thirteen Allied submarines had completed twenty seven successful passages through the strait. Although seven were sunk, the Turkish losses were much larger – two battle ships, a destroyer, five gunboats, eleven transports, forty four steamers and one hundred and forty eight sailing boats. Norman Holbrook and all the submariners who followed into the Dardanelles were trailblazers of extraordinary skill and courage, diving their early boats into perilous situations while devoid of any technical aids. Of the thirty-nine Victoria Crosses that were awarded for deeds of gallantry performed during operations designed to wrest control of the Dardanelles from Turkey, three were awarded to submariners. Lieutenant Norman Holbrook was followed in April 1915 by Lieutenant-Commanders Edward Courtney Boyle in E-14 and by Martin Nasmith in E-11 in May 1915.

Holbrook’s exploits made world news at the time but the small farming town of Germanton in Australia was taking a more than normal interest in the VC winner. When Britain declared war on Germany, Australia followed suit with the Prime Minister Andrew Fisher declaring that Australians were with England ‘to the last man and the last shilling.’ During the first months of the war, Australia began to undergo a fierce anti-German phase which escalated into repressive conditions for the Germans living in Australia. They had to register at local police stations and report weekly, were forbidden to buy or sell property and not permitted to speak German either in public or on the telephone. They were often fired from their jobs and a great many were placed in internment camps as well as being subject to many other archaic restrictions.

In the Australian state of New South Wales, approximately 400 kilometres inland from the coast, the town of Germanton was suffering a major identity crisis. The town’s name now seemed unpatriotic and the councillors and citizens decided to change the name to something more appropriate but to what? When news of Lieutenant Holbrook’s exploits and that of his crew fired the imagination of British subjects around the world, the problem was solved and Germanton was officially gazetted as ‘Holbrook’ in 1915. The first official Holbrook town council meeting was held on 24 August.5

When Lieutenant Holbrook was officially notified of the re-naming of the town, ‘in memory of the valiant deeds done by you in the Dardanelles,’ he wrote in reply; ‘I feel that no higher tribute could be paid to any man, and I wish to assure the Council and inhabitants of your town that I shall ever regard their adoption of my name with feelings of pride and pleasure, that humble effort of mine to serve my country in this critical period of its history should have deemed worthy of such distinguished recognition. I trust that some future time, it may be my good fortune to visit Holbrook and make the acquaintance of its loyal inhabitants.’

Later Career

Lieutenant Holbrook’s service after the sinking of Messudiyeh consisted largely of patrolling duties until August 1915 when he was slightly wounded by gunfire from an enemy ship which had first shown a white flag before the submarine closed it. Thereafter he was engaged in minelaying duties and was Mentioned in Dispatches for this work in July 1917. Service with the Grand Fleet in the submarine flotilla followed. In August 1918 he left the submarine service as a Lieutenant Commander to serve on exchange in the Russian cruiser Askold. He retired at his own request in 1920 and was promoted to Commander on the Retired List in 1928. In 1921 he became Chairman of Holbrook’s Printers and newspaper proprietors of which his father, Sir Arthur, had been a founder. During WW II he was recalled and served in the Admiralty Trade Division. His brother Leonard Holbrook served as Commodore Commanding HMA Squadron in 1931/32 and was later promoted Rear Admiral.

After World War One and the Second World War, the bond between the Holbrook family and the Australian town named in his honour grew strong. Holbrook visited three times before his death on 3 July 19766 and in 1982, his widow Mrs Gundula Holbrook donated her husband’s medals to the town. However, Holbrook the town was not content just to have a connection with the WW I hero. They wanted a more fitting tribute that would encompass not only Norman Holbrook but all the brave submariners who served in time of war and peace. After a lot of planning, official red tape, generous donations from the public and a most amazing gift of $100,000 from Mrs Holbrook, the town purchased the de-commissioned 90 m long submarine HMAS Otway. The Australian navy was astonished! A submarine inland? Otway was transported in sections on low loaders and reassembled by volunteers and trainees from a government employment program. The submarine was permanently sited in one of the town’s parklands and a first rate submarine museum was built nearby. In addition to Otway, there is a large scale model of B-11. The Submarine Memorial was opened during the Queen’s Birthday weekend on 7-8 June 1997 with Mrs Gundula Holbrook as the official guest. In 2009, the Australian War Memorial in Canberra acquired Commander Holbrook’s Victoria Cross which is now on public display.

Although Commander Holbrook now rests in St James Old Churchyard in Stedham, West Sussex in England, his trip up the Dardanelles and back in 1914 will always be remembered in the Australian ‘submarine town’ of Holbrook.

Footnotes

1 The Allied fleet tried three times to sail up the straits but the third attempt ended in complete disaster and the fleet was forced to withdraw, beaten and humiliated by a few inexpensive sea mines.

2 What the submariners of the time underwent due to the petrol fumes, thrill seekers today would call ‘petrol sniffing’

3 A jumping wire is strung from the bow to the stern via the conning tower to deflect a mine cable.

4 In the letter he wrote to his parents Holbrook modestly called his exploit the ‘stunt’.

5 This is the only Australian town to be named after a VC winner.

6 His first visit was on 9 March 1956. In 1965 Commander and Mrs Holbrook donated funds to establish a scholarship aimed at assisting local students enter High School. That scholarship continues today.

The author is indebted to Elizabeth Brenchley, co-author of Stokers Submarine published by Harper Collins in 2001 for permission to quote excerpts from the book and Lauren Ryan from the Holbrook Submarine Museum,

www.holbrooksubmarinemuseum.com.au for her invaluable assistance. Thanks also to the Greater Hume Shire Council for permission to quote from Lawrence Ryan’s excellent booklet Holbrook-The Submarine Town and use of their photographs.

Insert photo: Plan of Dardanelles – Popular Mechanics March 1915

Insert phot: Submarine B-11 – cyber-heritge.co.uk

Insert photo: Turkish Battleship Messudiyeh

Insert Photo: LT Norman Holbrook,VC, RN