- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval Aviation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Cris George

There was plenty of aerial activity attached to this year’s Fleet Entry celebrations in Sydney Harbour. What you might not know is that there was an aerial entry in 1913 too, though it wasn’t officially recorded. Thousands of onlookers along the foreshores saw the remarkable ‘Captain Penfold’ make a balloon ascent from Watson’s Bay. What happened was recorded by the Sydney Morning Herald of Monday 6 October:

‘As the fleet was on the point of entering the Heads the aeronaut dropped several bombs which exploded in mid-air and produced puffs of smoke as a salute. He also waved an Australian flag. The balloon rose to a height of 2,000 or 3,000 feet. The beautiful ascent and descent held the attention for a minute or two of the people and those on the boats that lay within the harbour. Perhaps it also interested the crews of the warships, for the balloonist was throwing bombs down from high up in the air to demonstrate its possibilities in wartime.

The balloonist was actually Vincent Patrick Taylor (1874-1930). He was a Sydney boy, member of an industrious family of shopkeepers who sold flowers, fruit and confectionery and ran a large catering business from a factory in Darlinghurst. His brother George Augustine Taylor (1872-1928) worked with Lawrence Hargreaves on kite development and other aviation experiments. George is acknowledged as leading contender for the first to fly a heavier-than-air aircraft in Australia on 5 December 1905. George Taylor’s wife, Florence Mary Taylor OBE (1879-1969), was an architect, an engineer and the first woman in Australia to fly a heavier-than-air aircraft. It was in a glider of her husband’s design and build, at Narrabeen on 5 December 1909.

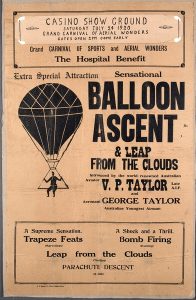

Vincent Taylor was articled by his family to learn the basics of law before entering Sydney University. He briefly entered politics, but was unsuccessful. He became a bookmaker’s clerk before gaining his own licence and working on racecourses around Sydney. But given the aviation leaning of his family Vincent almost naturally decided to become a balloonist and parachutist. It was reported that he offered an aerial pamphlet delivery service at £5 per 1,000 and clients included many important Sydney businesses. He also made well attended display balloon ascents at Randwick, Clontarf, Balmoral and Wonderland City (an amusement park near coastal Tamarama in Sydney).

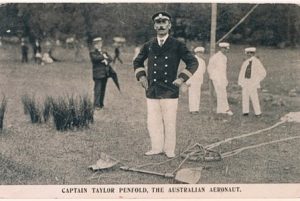

The restless Vincent signed on as a deck-hand on an American ship sailing for San Francisco at the end of 1906. He wanted to learn more about ballooning and parachuting from the professionals then working at Oakland, nearby San Francisco. For day-to-day income he worked as an advertising agent, an extra with several theatre companies, and a rep for a canvas awning firm. He introduced himself to the US balloonists as ‘Captain Penfold, the Australian parachutist’, although he had made no descents. The origin of his stage name remains unknown.

The unpublished biography of Vincent by his son George in the Library of NSW records that Vincent worked in San Francisco with a Thomas Scott Baldwin, who is remembered by the US National Aviation Hall of Fame as follows: Few men in the aeronautical community were better loved than Captain Tom. Inventor of the flexible parachute, builder of the first practical dirigible in America (1904), pioneer designer, builder and flyer of airplanes, his life was unrivalled as a showman, innovator and inventor for his nearly 50 years in aeronautics’.

Perhaps significantly, General ‘Billy’ Mitchell, early advocate of air warfare – most publicly against ships of the USN – was also an early student of Captain Tom, though this was later when Tom Baldwin managed the Curtiss Flying School during WW I.

Vincent made rapid progress learning balloon parachuting. It appears likely that during this period he also learned the materials required, the processes involved and the design of both parachutes and balloons, because he commenced the manufacture of these when he returned to Australia. Vincent soon caught the attention of the American public. On 6 May 1908, sponsored by the San Francisco Examiner newspaper, he made the first of several ‘attacks’ on the USN’s Atlantic Fleet as it entered San Francisco bay. After launching in his coal-gas filled balloon, he climbed through cloud, passing over the fleet and then from about 6000 feet parachuted into San Francisco Bay.

On 11 May 1908 he repeated the feat at night using various pyrotechnics and flares to simulate ordnance dropped upon the fleet as he descended. The first time he was cut free of his parachute by the boat’s crew from USS South Dakota. On the second occasion he landed next to USS West Virginia.

On 23 May 1908 he was involved in the launch and the subsequent breakup of an airship belonging to J.A. Morell of San Francisco. This giant craft was 450 feet long, 36 feet in diameter and had motors of 200 horsepower. Vincent, recorded in newspaper coverage as Capt. Frank T. Penfold, suffered fractures of both legs in the crash.

Late in 1908 Vincent arrived back in Australia. Beginning early in 1909 he made parachute descents every Sunday at Clontarf, usually from about 3,000 feet. He called his new balloon the Baldwin War Balloon and used a parachute of his own manufacture, named Empire, which had a canopy of red, white and blue material. The Australian flag was also usually included.

He was sponsored by businesses and local government to conduct balloon ascents and parachute descents at £25 a day. He favoured a costume of white pants, gold-braided blue coat and gold-braided peak cap, and he sported a curled and waxed moustache. An aneroid barometer was used to determine his altitude.

Vincent established a factory in Castlereagh Street, Sydney to make balloons and parachutes. The balloons weighed over two hundredweight, were made of Japara silk cloth and cost £45 and a parachute cost £14. He appears to have travelled to many regional towns in NSW and Victoria to give his displays, and often donated part of the takings to charity.

In late 1909 Vincent in partnership with his brother George established what was claimed to be the first aeroplane factory in the southern hemisphere. The enterprise opened in Surry Hills and volunteers commenced assembly of eight war kites and one large aeroplane. The aircraft, named Building Australia, was powered by a 30 HP engine made by Gibson and Son, Balmain. During December 1910 the first aviation carnival was held at the Royal Agricultural Society Grounds in Sydney, and although advertised as an attraction, Building Australia did not fly and Vincent Taylor entangled his balloon in overhead wires. There is no further mention of the Taylor aeronautical factory.

In 1912 Vincent went to England to seek his pilot’s licence in conventional aircraft and he received Royal Aero Club certificate No 376 after graduating from the Bristol School Salisbury Plains on 3 December 1912.

While in England he fitted in some balloon ascents and parachute descents including a well publicised ‘Santa Claus’ jump for a chocolate firm. As a consequence of a number of emergencies over a reported two days two passengers were rescued but without their costly movie cameras that had to be ditched to prevent the balloon falling into the sea. But the chocolate company received publicity beyond their expectations. One of his passengers during his ‘Santa Claus’ days was the famous polar explorer Hubert Wilkins (later Sir Hubert) who had served with the Australian Flying Corps.

On his return to Australia Vincent made what may have been the first B.A.S.E. jump in Australia, on Friday 5 June 1914. To test and prove an emergency parachute he had designed for airmen and for escaping from high buildings, he jumped from the North Sydney Suspension Bridge linking Cammeray and Northbridge, at a point 150 feet above the mudflats of Middle Harbour. The canopy opened in 40 feet. Vincent was reported as landing in the shallow water exactly seven seconds from the time he released the patent catch by which the canopy was attached to the ironwork of the bridge. On 30 June 1914 he made a similar jump from a 12-storey building off George Street in Sydney’s central business district. He was ‘hung up’ on a projecting obstruction and rescued by a crane. Nevertheless, he proved his parachute.

Although over age, in World War I Vincent joined the AIF as a driver. He served for two years with the service number 9081 as a member of 10th Battery, 4th Field Artillery Brigade, Second Division. He apparently applied for flying duties with the AFC but was rejected, reportedly due to a lack of availability of positions.

After the Somme battle of 15 November 1916 he was hospitalised for a short time and then returned to Sydney where he was medically discharged in 1917 because of his age and deafness which the examining Army doctors found had been caused by his parachuting and ballooning activities before joining the AIF. This denied him a war service pension.

Vincent returned to civilian parachuting in Sydney around regional Australia, supporting Australia’s war effort including with recruiting. Until 1918 he had jumped under the name ‘Captain Penfold’, but after WWI he jumped under his own name of Vincent Patrick Taylor.

In the 1920s Vincent returned to the US where he met his parachuting partners of earlier years, and continued his parachuting and stunt career until his death in 1930. Apart from reportedly working as a stunt man for movie companies, Vincent engaged in a variety of ballooning, parachuting and water activities in the US. He made parachute jumps off the Niagara Falls River Bridge and the Snake River gorge Twin Falls-Jerome Bridge in Idaho, 476 feet above the water. At about this time Vincent invented and manufactured a dry suit very similar to the now superseded Fleet Air Arm ‘Goon Suit’ of bygone years. He used this to travel down whitewater rivers and even once, while propelled by a double-ended paddle, to simulate a swimmer attack, once again on the US Fleet units.

Vincent’s views on parachuting were expressed in an interview in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on Tuesday 7 August 1928: ‘Parachuting is poetry of motion. In an airplane, one is being dragged along. In a free balloon, he is pushed by the wind, but in a parachute he is supported and carried down like a babe in its mother’s arms.’

But time was running out for balloon parachutists and other ‘daredevils’ as the Depression reduced the money the public had to spend on such spectacles, and also because aeroplanes, which proliferated as a result of WW I, attracted greater attention. In 1930, apparently destitute, he was hospitalised in the charity ward of the County Hospital, Jacksonville, Florida, suffering from a failure of his digestive system. Vincent apparently neither drank nor smoked and was a physical fitness enthusiast and the cause of his fatal condition is unclear. He died alone aged 56. He was buried with military honours in St Mary’s Cemetery after a requiem mass at the Church of the Holy Rosary. A military escort was provided by the Florida National Guard and his casket was draped with the Union Jack. The service and funeral were reportedly attended by representatives of the American Legion and local citizens.

In 1997 a musical about some of Vincent Taylor’s exploits was written and performed in Sydney, but he has no known commerative plaques or memorial to his name. His contribution to Australian aviation is overshadowed by the record of the achievements of others and he apparently is relegated to the ranks of eccentric showmen. That seems to be an unfortunate misjudgement. He was a pioneer who successfully and routinely undertook great personal risk to perform well in his profession. Vincent was also a fiercely proud Australian and perhaps above all an enthusiast.

As a minor prophet of maritime aviation, minor because it appears not many took serious notice of him, well before others Vincent demonstrated in basic form what he saw to be the warship’s vulnerability to attacks by aerial vehicles and also the utility of parachutes before these became an accepted safety system. After performing his ‘attacks’ on the USN fleet, he repeated the event during the RAN’S first entry into Sydney in October 1913.

Within the planning of the 1913 RAN Fleet Entry into Sydney many would have been aware of the emerging potential of the aeroplane as an observation platform and weapon carrier. Mr Eugine Ely, a member of the Glenn Curtiss stunt flying team had been the first to launch an aircraft off a ship from USS Birmingham on 14 November 1910. Commander Charles Rumney Samson RN repeated the feat from HMS Africa on 10 January 10 1912 and was the first to launch from a moving ship HMS Hibernia in May of that year.

The earliest official Admiralty view of aviation however favoured not the aeroplane but the airship as the more likely naval choice. But after an unfavourable beginning by these to a later useful operational service during WW I, during his first term as First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill established the first RN seaplane base on the Isle of Grain in December 1912, followed by others at Calshot and Felixstowe.

As has been the case several times since, control of Navy’s air component was the subject of delaying debate. Then on 1 July 1914 the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps became the Royal Naval Air Service. Formal aviation planning by the RAN had begun in June 1913 when our Naval Board stated a requirement for three aviation bases to assist with the defence of Australia. Each of these was to operate several reconnaissance ‘waterplanes’. The First Naval Member of the Naval Board, Rear Admiral Sir William Rooke Creswell, also identified the need for a Navy aviation school.

In mid 1913 the Australian Naval representative in London reported that despite the hopes and promises of things to come, the Air Service was a shore-based reconnaissance organisation with a reliable operating radius of about 100 miles. The report caused Admiral Creswell to opt, instead of the three seaplane stations, an air group of four seaplanes embarked in the planned submarine depot ship, which was to be fitted out with workshops and accommodation for the embarked seaplane detachment.

The necessary investment to establish this RAN aviation element was identified by the Naval Board but thwarted and postponed by the outbreak of WW I when all priority was given to the development of the Australian Flying Corps which had commenced recruitment in 1911 and flying training at Point Cook on 17 August 1914. RAN ships continued to gain aviation experience during their service with the RN including the embarkation and operation of RANAS aircraft. But that is another story.

At the time of the first RAN fleet entry into Sydney in 1913 naval aviation was at a very early and theoretical stage. No naval or any other aircraft are known to have been part of the ceremonial occasion. But an archival search of the newspapers covering the fleet entry found the Captain Penfold report in the Sydney Morning Herald of Monday 6 October 1913.