- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Dr Simon Smith AM FRHSV

Dad, what did you do in the war? A question most baby boomers would have posed as they grew up and became conscious of the impact of World War II. Almost certainly any answer, if one was given, would have been minimal. Understandably, people closely exposed to the horrors of the war were keen to put the experience behind them. Instead, fuller answers usually came from other family members or friends. In my own case it was my mother Nancy Smith (1921-1995), as the keeper of the family’s oral history, who shaped my understanding of what my father Peter Smith had done whilst in the Navy. However, it was not until 2023 when historian Janet Roberts Billett published her excellent book The Yachties: Australian Volunteers in The Royal Navy 1940-45 (2023), that I was able to fill in the gaps and understand what a fascinating story it was. That book chronicled a small group of approximately 500 Australians who were recruited from Yacht Clubs and beyond to join the Royal Navy as part of the Dominion Yachtsman Scheme. Most of these ‘Gentleman Yachties’ became officers. As a group they are one of the most decorated of all Australian service units

Peter Fitzjohn Smith (1914-1991) was born in the looming shadow of the First War. His family lived in Fitzroy, then a poor inner suburb of Melbourne. His father was a French polisher and his mother a cleaner. As a ‘Roy Boy’, things were tough although his mother’s determined Methodist faith had seen him spend his last two years of schooling at Wesley College, Melbourne’s Methodist private school. There, his reports gave faint praise when they noted ‘he is a reliable worker, who should succeed (but) his weakness is arithmetic (which) is mainly due to carelessness.’ There was irony in the last comment given his eventual profession as an accountant. After leaving school he had clerical jobs while he studied accountancy by correspondence. However, these were Depression years and when he was 21, he was able to find a full-time job with the British Phosphate Commission. This saw him spend 1935 to 1936 working as a clerk on OceanIsland (Gilbert Islands Group), an isolated phosphate-rich atoll atop the equator. Hot and humid, it was hardly a Pacific paradise. The only way to get to and from the island was by the company steamer MV Triaster. This was my father’s only nautical experience to that time.

Returning to Melbourne, now fully qualified, Dad found work as an accountant with the Egg and Egg Pulp Marketing Board but as the Second World War got underway his focus was on personal life and in December 1941, aged 27, he married at the Methodist Church in Northcote. Mum would say that it was a time that the second front was shaping and each Saturday the scene in High Street Northcote was of ‘wall to wall’ couples as they hurried to marry before the groom went to war. A short honeymoon at Lorne followed before Dad entered Flinders Naval Base (HMAS Cerberus) in January 1942 for training. It was the start of a three-year separation from home. Why he was selected for the Yachtsman Schemeis unclear. To that point his only nautical experience was steaming to and from Ocean Island in the mid Pacific. As it happened his intake was the last to be sent overseas to the Royal Navy. As the number of available yachtsmen had fallen away the recruitment focus had shifted to people with mathematical aptitude who could be trained as navigators and officers. Accountants apparently met that criteria. Also of possible relevance was Dad’s two years at an elite private school, reflecting an underlying class bias in selection for potential officers. What is clear is that the navy was second choice as an earlier attempt to join the air force was unsuccessful because he was seen as under weight.

After five weeks basic training at Flinders things moved fairly quickly. By the middle of February 1942, as an ordinary seaman, he was aboard MV Aorangi, a Union Steamship Company liner requisitioned for the war effort. They were bound for Halifax, Canada via the Panama Canal. Dad would later learn that while he was at sea during February/March it was a period of much U-boat activity off the coast of Florida and many Allied ships were sunk. He believed the safe passage of Aorangi may have reflected its faster steaming speed of 15 knots. No sooner had she arrived in Halifax, then Aorangi set off again, in convoy, this time for Glasgow. She had on board a full complement of troops and equipment.

From Glasgow Dad proceeded to Fareham near Portsmouth for entry training of seven weeks at HMS Collingwood. After that he was drafted with a ‘Yachtie’ friend Alan McIntyre (1916-1988), to HMS Georgetown, an American destroyer made available to Britain under the Lend Lease programme. They were to join the ship in Glasgow but as she was at sea, they had to wait for her to arrive. Most likely this was when Dad enjoyed the hospitality of the Haig family of whisky fame, an example of the friendship extended to visiting uniformed members of the Empire. While on leave Dad would play a round of golf at St Andrews, the home of golf; it had been made available to servicemen. A golfing experience only matched many years later when he played a round with Greg ‘the Shark’ Norman in a Melbourne Pro-Am.

Convoy Escort Duty

Service in HMS Georgetown was no pleasure cruise. In late September 1942, as winter loomed, she crossed the Atlantic to Halifax via Iceland. For the next three months she was engaged in convoy escort duty on the east coast of the US and Canada from Boston to St Johns, Newfoundland. Lasting impressions for Dad were his sea sickness on the first day of each voyage, the severity of the North Atlantic storms and the experience of being part of a whaler’s crew searching for survivors amongst wreckage after the sinking of a merchant ship. Just before Christmas 1942, he left Georgetown and boarded the Cunard liner HMT Queen Elizabeth for another Atlantic crossing, to Glasgow. That ship, at that time the largest passenger liner ever built, was fully laden with troops as the Allies slowly prepared for the next phase of the war. Dad recalled that Queen Elizabeth travelled without escort as she was too fast for any destroyer to accompany her. Her average Atlantic crossing took three days and eight hours.

Upon return to Glasgow Dad and Alan McIntyre proceeded to Hove, near Brighton on the south coast, for officer training at the shore facility, HMS King Alfred. After two months both men emerged as temporary sub lieutenants RANVR. After hastily purchasing a full officer kit from the naval tailors Miller, Rayner & Haysom (London) for the princely sum of £44.1.5d, in May 1943 Dad boarded the requisitioned French liner HMT Pasteur at Liverpool. He was to make yet another Atlantic crossing, this time to New York. His posting was an appointment as gunnery and watch keeping officer with Landing Ship Tank LST 237 that was still under construction at the shipyards in Evansville, Indiana. Delivery of LST 237 would take a further two months and during that time Dad was billeted at the art deco Hotel Barbizon Plaza (now Trump Parc). Two floors of the hotel were reserved for Royal Navy officers based in or passing through New York. While in residence they were likely to have been served tea every afternoon by New York society ladies. In New York dad spent periods as a duty officer interspersed with navigation classes at Asbury Park in New Jersey. That seaside location became known as ‘HMS Asbury Park’, so numerous were the British sailors on ‘rest and recreation’ awaiting assignment to Lend Lease ships. The delay also enabled Dad to connect with Smith relatives in Cleveland, Ohio. First and second cousins, that branch had emigrated from Cambridgeshire in the 1880s at the same time the Smiths established in Australia. They were thrilled to welcome their Australian cousin, particularly ‘Lieutenant Smith of the submarines’, the rank of sub lieutenant not being used in the US navy where the rank was Ensign.

By July 1943, construction of LST 237 was complete and she sailed down the Mississippi to New Orleans to be handed over to her British crew. Dad had also travelled to New Orleans but by special train comprising ships’ companies for three LSTs. Family legend recounts that the officers in charge of the train clubbed together to buy supplies of Coca Cola to sell to the enlisted men, at a small profit. On the three days the journey took they would also stop the train in remote spots to enable the enlisted men to stretch their legs without disappearing.

From three pages of recollections written by Dad nearly fifty years after the war we know that LST 237 then undertook a ‘shakeout trip’ from New Orleans to Philadelphia via Chesapeake Bay. At Philadelphia, a full complement of American troops, stores and trucks were loaded. All were bound for North Africa. By early August 1943, LST 237 was ready and she sailed to the massive naval station at Norfolk, Virginia to join a squadron of six LSTs. They were all to move in convoy across the Atlantic, and it took seventeen days to arrive at Algiers in the Mediterranean. There, after the troops were disembarked, four of the LSTs continued on to India while LST 237 and another remained in Algiers.

The Battle of Anzio

Between September and December 1943, from a base in Algiers, LST 237 would make many trips to Sicily and Naples and the occasional trip to Sardinia and Malta, transporting British and American troops, trucks and tanks. By January 1944, two years after Dad had joined the navy, all was ready for what became known as the Battle of Anzio. That battle commenced with an amphibious landing (Operation Shingle) on the west coast of Italy. LST 237 had prepared in Naples for the 22 January 1944 landing at Anzio where they unloaded British troops, trucks etc. Years later Dad recalled that his vivid impressions of this landing were the shelling of the LST by German artillery from the high slopes overlooking the harbour and the occasional dive bombing by the single seater Focke-Wulf fighters (FW-190s). For the next two months LST 237 continued to ferry reinforcements to Anzio from Naples until April 1944 when she was ordered to England to make ready for the next major phase of the war, Operation Overlord: the D Day landings.

D-Day: A Huge Armada

In Britain, home base was Devonport on the south coast. After a short stay there LST 237 proceeded to Harwich on the east coast to make ready for D Day. After loading British troops and equipment from the 50th Division, LST 237 sailed for Normandy on the evening of 5 June 1944. Sailing in convoy with other LSTs they arrived off Gold Beach (Arromanches) at 11 am on 6 June 1944 but did not unload troops on the beach until the next day. The landing would see Bayeux become the first French town liberated following the invasion. Dad’s memories of the invasion included the huge armada as far as the eye could see. Anchored as they were next to the cruiser HMS Ajax, they rolled from side to side every time that ship fired her guns. Late in the day they watched in awe as a formation of 1200 Flying Fortress bombers flew over towards France. LST 237 would continue to transfer reinforcement troops to France over the next few days until steering problems resulted in a collision at Southampton and a hole in her bow. That was the end of her channel crossings and she was directed to Appledore in Devon for experiments in launching Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) from LSTs. It was also the end of Dad’s participation in the European operations. In November 1944 he was directed to make ready for onward passage to Australia. It was a recognition that it was now a European land war mainly involving the British and Americans and Australian naval personnel were now needed in the southern hemisphere. His final confidential report from LST 237 noted he was a ‘good mixer’ and that he had carried out his duties as Gunnery Officer to the ‘every satisfaction’ of his commanding officer.

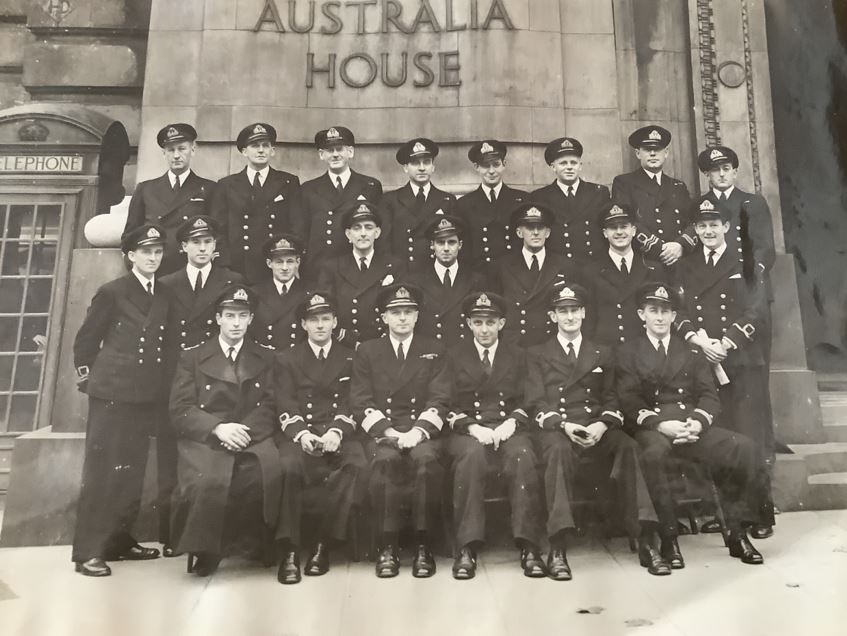

Before leaving Britain, Dad was one of 24 Australian naval officers who were given a ‘send-off’ reception at Australia House in the Strand, which was reported on in Australian papers. Just before Christmas 1944, he would embark for Melbourne from Liverpool on the requisitioned Blue Funnel liner SS Nestor. Six weeks later, having travelled via Durban and Cape Town, as his own father had done as an immigrant child in the 1880s, he arrived in Australia. It was almost three years to the day since he had joined up and had last seen his wife. He would spend the next the next four weeks enjoying married life in Melbourne before in March 1945 being posted to HMAS Westralia as Confidential Book and Watchkeeping Officer. It would be his last naval appointment.

The main role of Westralia was to transport troops from Australia to New Guinea and further north as required. In a quirk of fate for Dad, it was a return to the area around Ocean Island where he had spent some of the 1930s. Westraliawould participate in landings along the Borneo coast including at Tarakan, Labuan and Balikpapan. In August 1945 she would also land 1000 troops in Bougainville in New Guinea. She would spend VJ day (15 August 1945) in the Solomons and thereafter moving troops about including a large number of American ‘Seabees’. After collecting 1500 troops from a fighter base at Morotai Island Westralia proceeded to Amboina (Ambon), the confronting scene of a large prisoner of war camp. Dad observed that the few remaining prisoners ‘were in poor physical condition but one could not but admire the courage of men who could relax with a smile at their tales of fight for life and self-preservation’.

Westralia would spend the remaining months of 1945 transporting troops home for leave and eventual discharge. In mid-January 1946, Dad completed his final voyage as she returned to Brisbane. He would be discharged from the navy in February 1946 after four years of service. The next year he received a letter from the Secretary to the Naval Board thanking him for his ‘service during the War’. He would put the navy and the war behind him as he began a family life including three children and the rebuilding of his career as an accountant.

He never participated in the Anzac Day March. His view was that it was for the army and their larger groupings. Indeed, in his time at sea he was often the only Australian officer amongst the crew. His only concession to wartime service was his attendance at the annual London Naval Officers Dining Club Dinners. They were held at the Melbourne Naval and Military Club. His friend Alan McIntyre disappeared from his life but not before Alan had a short marriage to Vogue editor Shelia Scotter. Dad died from heart failure in 1991, aged 77. In a fitting tribute members of the Westralia Association attended the funeral and provided a proper naval send off with the casket draped in the White Ensign.

Lest We Forget:

Lieutenant Peter Fitzjohn Smith RANVR Rtd.