- Author

- Francis, Richard

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2003 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

I HAD NEVER SEEN an Admiralty Writ before but was aware of the folklore, that if one was issued to seize a ship as security for some unlawful action, the Admiralty Marshal or Provost came aboard and nailed the writ to the mast to effect the legal claim. In the sailing ship days gone by it would have been a relatively easy matter to do this with wooden masts but not so now.

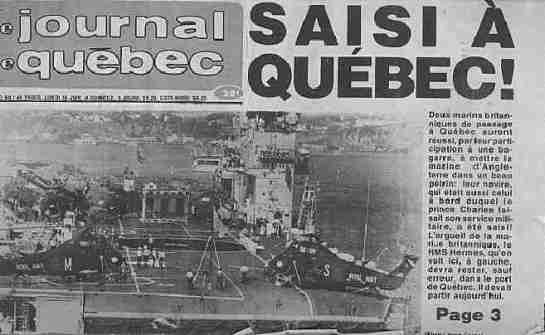

My ship at this time was the amphibious commando carrier, HMS Hermes, and we had been conducting NATO amphibious exercises and good will visits on the eastern seaboard of Canada that spring. After a successful visit to the largest Canadian city, Montreal, we had sailed down the St Lawrence Seaway for a final port visit to the ancient bastion of French-speaking Canada, Quebec. We had enjoyed a fine welcome, explored the historic and scenic areas, practised our schoolboy French, and realised that once the locals appreciated that we were not American tourists but British servicemen (we had a full Royal Marine Commando embarked) everything turned out well. On the final day of our visit, a Sunday, the ship was open to visitors and several thousand of the local inhabitants turned out to come aboard. I was Duty Lieutenant Commander, and spent most of the afternoon on deck supervising the overall arrangements, which had been very successful. Shortly after the ship was closed to any more visitors and the remaining few hundred were being herded ashore over the gangways I noticed a small group of businessmen escorted by a policeman come aboard the after officers’ gangway. In the absence of the OOW, I asked their business and was greeted with a babble of French and the production of a stiff brown envelope, gathering that they wished to view the mainmast. Innocently, I began to explain that this warship had a steel mast and that it was far and remote on the island superstructure, well away from the quarterdeck.

My suspicions began to be aroused and I opened the envelope, to the satisfaction of those present, to reveal a handsome parchment document embossed with gold lettering. A few more simple questions made me understand that it was some sort of legal summons, but glancing at it I discerned that it was all written in French, beginning: ‘La Reine Elizabeth du CANADA a dit . . . etc. etc’. Having accepted the document all present seemed to relax, and so did I, wishing them a cordial ‘Bon Jour’ and ‘Au Revoir’ as they disembarked over the gangway. Then I returned to my other priorities, observing the duty watch escorting the last remaining visitors ashore. Some half hour afterwards my Captain returned on board in plain clothes and asked me how the ‘Ship Open to Visitors’ had gone and I was able to reassure him that this had been highly successful, without any incidents to report, and he proceeded below to his cabin. Then I remembered the legal document in its envelope, so I followed him below to his cabin where he was relaxing with a cup of tea. ‘This document was delivered onboard, Sir, and my rusty French indicates that it is some sort of legal summons to do with one of our libertymen ashore yesterday.’ The Captain took the envelope from me and absent-mindedly sat down again with his cup of tea and I returned on deck.

About ten minutes later the Captain’s buzzer sounded at the gangway and I went below again to report to his cabin. He seemed somewhat agitated: ‘Don’t you realise what this is?’ he said ‘It’s a bloody Admiralty Writ! Go and find the Commander immediately.’

* At this time Prince Charles had already left the ship (in Montreal) to return to Royal duties.

The buzz gradually spread through the ship at about breakfast time the next morning, as we prepared for sea, homeward bound. The telephone lines had rung hot that night between Quebec, the ship, Ottawa, the British High Commission, and Whitehall in London. We had been deployed for several months and all thoughts were of our homecoming. Before disconnecting the phones before sailing, several members of the ship’s company took the opportunity to ring home and reported that there seemed to be some concern in UK that the ship was to be delayed sailing in Canada and a big political storm was brewing. This was later confirmed by an overseas BBC news broadcast ‘HMS Hermes has been arrested by Canadian authorities in Quebec with an Admiralty Writ nailed to the mast (sic)’. The sailors began to be alarmed and their concerns were passed upwards by the divisional system, although there had been no outward indication that actual sailing at 0900 had been delayed. A large crowd of local Quebecois and well-wishers had gathered around the ship’s berth and a contingent of media representatives arrived, curious at to whether the Mounties would prevent the ship from sailing.