- Author

- Gordon, John

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 1989 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This account is written from memory, after reading it in “We Captured a U-Boat” by Rear Admiral Gallery, USN. First published in about 1960.

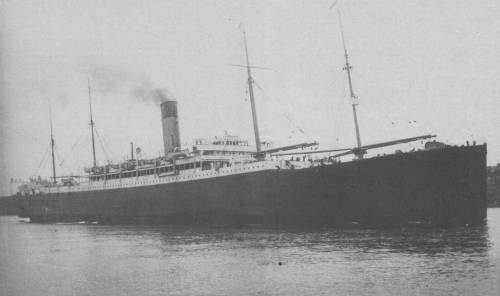

The Ceramic was sunk about 400 miles west of the Azores in December, 1942. She was built about 1912 and was owned by the Shaw Savill and Albion line when she was sunk and spent all her working life on the England-Australia run.

After war broke out, some ships had to be used to carry people with a legitimate reason for travelling between England and Australia and the Ceramic was chosen. She made several successful trips. It was a calculated risk which meant that it was okay so long as it succeeded. She almost always carried some women and children.

On her last voyage she sailed from Liverpool with a convoy bound for North America and stayed with it for security until it reached mid-Atlantic. She was carrying about 400 passengers and a crew of about 250.

on her inaugural passage to Newcastle, NSW Sunday, 19 October 1924.

In mid-Atlantic she turned south and left the convoy to proceed unescorted to Capetown. Some days later at about the latitude of the Azores, late one afternoon, she was sighted by a German submarine running on the surface which thought she was a troopship. This submarine had been sent out there by Doenitz on the off chance of picking up the odd ship that might be travelling alone. It was not a popular arrangement, as day after day went past and no ships appeared.

The submarine correctly estimated the Ceramic’s course and speed, she was not zig zagging, and set a course to intercept at about midnight.

At midnight the Ceramic appeared and was torpedoed. She stopped and passengers were ordered to their boat stations, the ship however remained afloat and they were reluctant to get into the boats. After about 20 minutes the submarine put another torpedo into her. The Ceramic’s captain now knew that the submarine knew exactly where he was, so ordered all people into the boats and put on all lights. One lifeboat was hung up on one end on the way down spilling its passengers into the sea where they perished. A third torpedo went into her but still she floated and it took a fourth to finally sink her.

Of the approximately 650 people aboard her, about 150 had probably been lost in the actual sinking, leaving 500 people still alive in lifeboats, liferafts or just in the water.

The submarine came to the surface and moved slowly forward. The submarine’s captain was named Henke, and until this time he thought he had sunk a troopship and was very surprised to see women and children in the boats and in the water.

Several people had managed to clamber onto the submarine’s after deck and he ordered a few men to push them over the side, which was done, but some clambered back to lay on the deck. Henke tried to find the Ceramic’s captain but without success. He saw a man in uniform on one of the rafts. His name was Sapper Munday of the Royal Engineers and he was taken prisoner, the only one taken.

Henke then ordered ‘full speed ahead’ and then ‘dive’. One of his crew told him that there were people on the after deck but the ‘dive’ order stood and that was the end of them.

Previously his radio operator had told him that the Ceramic had sent an SOS but that he doubted anyone had heard it, due to heavy static and he asked if he could send another one for her. The answer was ‘No’!

When the submarine left the scene there must have been nearly 500 people still alive, of which about 250-300 would have been in the boats, the rest on rafts or clinging to pieces of wreckage and given reasonable weather about half could well have reached the Azores or been picked up by passing ships, but early in the following morning the weather deteriorated till the next day it blew a full gale. By the next night probably no one from the Ceramic was left alive (except Sapper Munday) for none were ever seen again.