- Author

- Hobbs, D.A., MBE, Commander, RN

- Subjects

- WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2000 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

“Whatever its demerits, into the execution of this plan as it stood the squadrons put the limit of human endeavour; that they achieved so great a measure of success against a not easily accessible and heavily defended target justifies an outlook of high promise for the future besides being ever most creditable to the officers and men concerned.”

Vice Admiral Sir Phillip Vian 10 February 1945

The Target

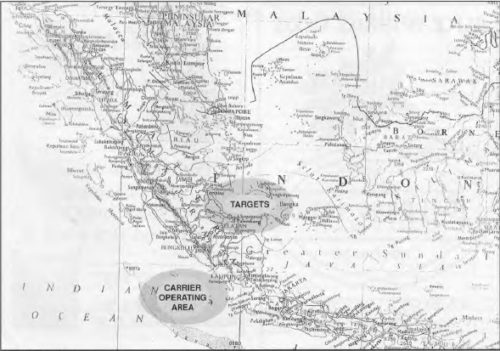

The city of Palembang lies in south eastern Sumatra on the north bank of the River Musi, forty miles from its mouth. In 1945 it was an important centre for road, rail and river transport and was the Headquarters of Japanese Forces occupying Sumatra.

Five miles downstream the two target refineries lay on the south bank of the Musi, divided by the River Komerine at the point where it joined the Musi. Pladjoe, to the west, owned by Royal Dutch Shell was the largest oil refinery in the Far East. Key installations were widely dispersed and largely duplicated making its neutralisation more difficult. Soengei Gerong, to the east, had been built by Standard Oil and was second in production only to Pladjoe. It was more compact with less duplication of key equipment. Between them they were capable of producing three million tons of crude oil a year and supplied 75% of the aviation spirit needed by the Japanese.

Both refineries were captured in February 1942. Engineers had attempted to wreck them but in both cases destruction was incomplete and production had been resumed by the end of 1942. Engineers from both Royal Dutch Shell and Standard Oil assisted British Pacific Fleet Staff in building models of the refineries and in planning the most effective way to attack them with precision air strikes.

The Japanese Defences

Two battleships, two heavy cruisers and two destroyers were sighted in Singapore on 18 January. It was believed that a few motor torpedo boats and light escort vessels might be based on Batavia with the possibility that some might be encountered off the west coast of Sumatra. A German U-Boat, which had been operating off the coast of New South Wales was thought to be returning to its base via the Sunda Strait. Others, based on Batavia were believed to be about to set passage for Germany via the Sunda Strait and the Cocos Islands. No Japanese submarines were reported in the area.

The main threat came from Japanese air forces in the region. These were believed to comprise 50 “Tojo” and 30 “Oscar” fighters in southern Sumatra together with 4 “Dinah” reconnaissance aircraft. With the plentiful supply of gasoline in Sumatra, many of these aircraft were used in operational training squadrons and the aircrew included a high proportion of instructors.

Japanese Forces in Sumatra could be reinforced at short notice from Singapore and Java. 36 “Oscar” fighters and 25 other aircraft including torpedo and medium bombers were available in the former and 30, including 10 “Zeke” fighters in the latter. A further 140 aircraft equipped training squadrons in Java which were known to include at least 10 “Oscar” and 5 “Tony” fighters.

No regular deep patrols were known to be flown from southern Sumatra or Java although occasional reconnaissance sorties were flown by “Dinah” aircraft from Mana airfield over the Cocos Islands which had never been occupied by the Japanese. These had covered the sector 165 to 270 degrees from Mana out to 325 miles and, on occasion, 435 miles.

A vigorous reaction was expected from the fighter defences based on airfield around Palembang. The “Tojo” was a good fighter but much would depend on the key element of surprise, how much warning the enemy got to position his aircraft and how good their individual pilots were. Recent encounters by the Eastern Fleet and during the strike on Pangkalan Brandan suggested that the opposition was not as formidable in fact as it looked on paper.

Enemy radar stations were known to exist at a number of locations including, it was suspected, Engano Island and the approaches to the Sunda Straits from the south.

Formation of the British Pacific Fleet

Although Churchill had promised a British Fleet to fight alongside the United States Navy in the Pacific during 1944, the creation of the necessary logistical support delayed its formation. There were many in the United States, including Admiral King, the Chief of Naval operations, who did not believe the Royal Navy capable of fighting the sort of open ocean carrier warfare that had developed in the Pacific. In the west and in the Indian Ocean the RN had relied on sea operations of short duration returning to one of a widespread system of bases for replenishment. A British fleet of auxiliaries capable of supplying the fighting units with everything they needed in protracted operations at sea simply did not exist and had to be created from scratch.