- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- None noted

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Australia I, HMAS Sydney I

- Publication

- December 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Lieutenant Commander Desmond Woods, RAN

This article was presented by the author at the Anglo-German Naval Race and WWI at Sea Conference held at Portsmouth, England in July 2014.

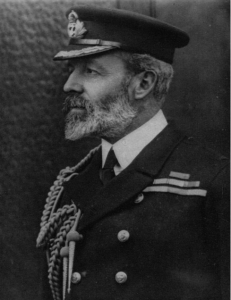

On the morning of 4 November 1914 news reached the Admiralty of the disaster that had overtaken Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock at Coronel on the evening of 1 November. Cradock and all 1,600 men of his outclassed, under- gunned and obsolete cruisers had been destroyed – without inflicting any serious damage on Vice Admiral Maximillian’s von Spee’s armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorstand Gniesenau and his cruiser escorts. At the Admiralty it was the first day of Admiral ‘Jacky’ Fisher’s return after taking over from Prince Louis of Battenberg as First Sea Lord.

As the scale of the defeat and loss of life became apparent Fisher demanded to know where ‘his greyhounds’ had been. Specifically Fisher wanted to know why von Spee’s armoured and light cruisers had not met the fast powerful battle cruisers that he had built to, in his phrase, ‘eat German cruisers as an armadillo eats ants.’

The First Lord, Winston Churchill, reacted swiftly asking among many other questions where was the most powerful warship in the Pacific, HMAS Australia? It must have been a rhetorical question as Churchill knew perfectly well that the RAN flagship was patrolling the Pacific off Suva looking for von Spee. What she was still doing there in November weeks after the German Squadron had left the mid Pacific was a more difficult question to answer.

Kaiserliche Marine

Throughout September and October, as von Spee made his way across the Pacific, Churchill himself had denied Cradock the powerful reinforcements for which he had asked. Instead he sent him the slow and unreliable pre dreadnought HMS Canopus. Because she carried 12 inch guns Churchill romantically described this reserve-manned elderly battleship with worn out machinery as the ‘citadel’ round which Cradock’s squadron was to concentrate. Churchill had no personal navalexperience and appears to have believed that the calibre of a ship’s guns could be used to assess her total fighting power, regardless of all other factors including her age, her stateof manning and general battle readiness. Cradock soon discovered that the lumbering Canopus was nothing more than a steel weight that inhibited rather than enhanced his ability to manoeuvre and fight.

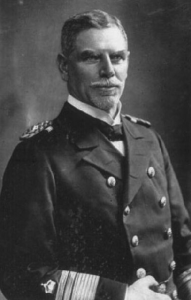

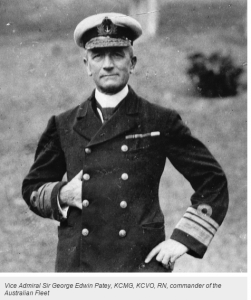

Had Fisher been deploying the fleet from the start of the war — rather than Churchill, Battenberg and the Chief of War Staff at the Admiralty, Vice Admiral Sturdee, — it seems at least possible, that Cradock would have had HMAS Australia at the Falkands as his ‘citadel’ ship. An equally possible scenario is that Rear Admiral Sir George Patey flying his flag in Australia, would have defeated or disabled von Spee at Samoa in September. Australiahad eight long range 12 inch guns with which to engage the 8.2 inch guns of the two German armoured cruisers. Three RAN cruisers, HMA Ships Melbourne, Sydney and Encounter would have scouted for Australia before taking on von Spee’s light cruisers. If von Spee had evaded Patey in the Pacific and reached the coast of Chile then Cradock’s ships Good Hope, Monmouth and Glasgow could have been under the protection of the fast and powerful Australian ship. In both scenarios the Germans’ main armament would have been outranged, and Australia’s heavy armour piercing 12 inch shells would have rained down on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau till they were disabled. They would have met their match. Patey would probably have damaged and possibly sunk one or both of the armoured cruisers. Whatever the outcome of an engagement in the Pacific von Spee’s plan to enter the Atlantic around Cape Horn and attack shipping routes in the South Atlantic, as he fought his way home, would have been defeated.

Counterfactuals are not history and are necessarily speculative, but it seems reasonable to assume that had Patey and his ships been released from the central Pacific in good time to pursue von Spee, then the gallant Cradock and his doomed sailors might have lived to fight another day in better ships. The Royal Navy would have avoided its worst defeat at sea for over 100 years. Why that possible outcome did not happen, and tragedy and disaster ensued instead, is the subject of this paper.

The new strategic calculus in the Far East and Pacific in 1913

In October 1913 the strategic calculus in the Pacific shifted dramatically in favour of British maritime interests when the Australian Fleet Unit, led by the new battle cruiser HMAS Australia, steamed into Sydney harbour. With the flagship were two Chatham class cruisers, Sydney and Melbourne, build for the RAN and a third older cruiser, Encounter, on loan from the RN. Rear Admiral Patey relieved Admiral Sir George King-Hall, the last of the RN’s commanders of the Australian Station. The Australian government had bought and, with the assistance of the parent navy manned, a formidable maritime deterrent. The persistent colonial fear that in wartime Australia would have its ports blockaded or bombarded, and its trade routes raided by the German East Asia Squadron was lessened but not eliminated. Australians rejoiced as they welcomed their new Navy and politicians basked in the reflected glory of this long awaited maritime muscle. In May of 1914 the deterrent power of the guns of the new fleet was augmented by two E class submarines with the capacity to attack German ships with torpedoes.

August 1914

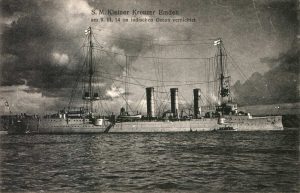

Nine months after the arrival of the Fleet, on the day war was declared, HMAS Australia steamed out of Sydney in all respects ready for battle. She would not return until 1919. Admiral Patey and the young RAN were ready for offensive or defensive operations, depending on what von Spee, and the Naval Staff in Berlin were planning for the East Asia Squadron. In 1911 Berlin had reinforced the Squadron with two modern armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gniesenau and several fast light cruisers and had given this prized command to Count von Spee, a respected commander and a man of undoubted personal courage.

Berlin’s Pacific war plan

The German Naval Staff’s Pacific war plan was to wage a cruiser war – against trade routes in the South China Sea, to the north of Australia and in the Indian Ocean. German archives reveal that this was the strategic intention in the years before 1913 and the arrival of the RAN Fleet Unit. Berlin took the view that food and raw materials from Australia and New Zealand were essential to Britain sustaining a long war and attackingthem justified the inherent risks to the commerce raiders of meeting more powerful warships. It was assumed in Whitehall that the German Squadronwould operate from its naval base at Tsingtao in northern China. British naval war plans called for Vice Admiral Sir Martyn Jerram, C-in-C China Fleet based at the British concession Wei Hei Wei, to attack Tsingtao as soon as hostilities were declared.

The RN’s China Fleet War Plan thwarted

When the opportunity came Admiral Jerram was in position to execute the Admiralty’s pre-war plan with his powerful armoured cruisers HMS Minotaur, HMS Hampshire and two modern light cruisers. On the point of carrying out his orders Churchill, supported by Sturdee, signalled Jerram giving him orders to sail south to Hong Kong to join the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Triumph which was unmanned and in dry dock. Jerram was furious and wrote to his wife:

‘All being ready I raised steam and was on the point of weighing to proceed to a line to the south of Tsingtao, my recognised first rendezvous in the war orders submitted by me and approved by the Admiralty. To my horror, I then received a telegram from the Admiralty, dated 30 July to concentrate at Hong Kong, of all places, just over 900 miles from where I wanted to go. I was so upset that I nearly disobeyed the order entirely. I wish now I had done so.’1

The cost of not capturing SMS Emden at Tsingtao

This reversal of plans by the Admiralty was to have profound ramifications and the rationale for it was never satisfactorily explained after the war by Churchill. There was no threat, real or imagined, to Hong Kong to justify Jerram being despatched there. Had Jerram been permitted to attack Tsingtao on the declaration of war he would not have caught Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which were far to the south east in the Caroline Islands, but he would have captured the fleet train and colliers in Tsingtao which instead survived to join von Spee at Pagan in the German Mariana islands in the Western Pacific. It was these ships that fuelled and supplied the German squadron across the Pacific.

Most significantly, Jerram would also in all likelihood have caught Emden and her collier Markomania and sunk or captured them. That action would have avoided the later loss of 16 British ships and their cargos that Emden’s Captain Karl von Müller captured or sank in the Indian Ocean. His raidingstopped British shipping fromsailing to and from Indian ports for several weeks. Emden’s destructionwould also have prevented von Müller sinking a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer at Penangand the burning of the British oil storage depot in Madras. With Emden stopped before she began her successful cruiser war, Jerram’s armoured cruisers Minotaur and Hampshire could have been available for the main event — the pursuit of von Spee.

Instead the moment for a surprise attack was lost; Jerram was ordered south and Karl von Müller, to his surprise and relief, found that his home port was still open to enter and leave. After coaling and storing he escorted the converted armed merchant raider Eitel Frederich and von Spee’s fleet train, including the heavily laden colliers, out of Tsingtao, and proceeding to join his admiral at Pagan. Jerram, languishing pointlessly at Hong Kong, had effectively been played out of the war in the Pacific by the Admiralty.

Franz Joseph, Prince von Hohenzollern, the Kaiser’s nephew, serving as Emden’s second torpedo officer, wrote in his memoirs of the surprise that he and his fellow officers felt at their freedom to enter and depart from Tsingtao in these last days of peace and the first days of war: ‘Only later did we learn that Admiral Jerram had intended to cruise outside Tsingtao and seize any of our ships he encountered. This had always been a possibility. What a rich prize the Royal Navy would have gained as the greater part of our colliers and supply-ships lay in Tsingtao. Happily we had an involuntary ally in Winston Churchill who ordered the British Squadron to assemble in Hong Kong. This bought us time we could not otherwise have enjoyed.’2

Patey’s ‘raid’ on Rabaul – 11 August 1914

Von Spee’s signals to his cruisers were heard but were not able to be decoded for meaning by naval intelligence staff in Navy Office in Melbourne.3The code breakers could not give Patey the German Squadron’s exact location, but he was told that the signals appeared to be strengthening daily. Navy Office deduced that von Spee was steeringsouth east, and made the reasonable assumption that he could be heading for Rabaul, the main port in German New Guinea.

As a consequence of receiving this intelligence Patey steamed the RAN fleet unit to Simpsonhafen. He mounted an operation on 11 August to surprise the Germans ships he hoped were there with a night torpedo attack using his three destroyers and HMAS Sydney. With Sydney waiting as their support ship, the blackened destroyers cleared for action and slipped into the anchorage and found nothing. The signal strength intelligence was misleading; the harbour was empty. Von Spee was at still at Pagan, 3,000 kilometres to the north, where his fleet was monitoring signals from the German WT station near Rabaul at Bita Paka. He learned from these signals that just six days after the war had been declared the RAN had made a raid on a German port, 3,000 km from its base in Sydney. Von Spee now knew that there was no safe German base for his ships in the South West Pacific and he appreciated that he was opposed by a powerful Australian Squadron, capable of swift deployment and which was actively hunting his ships. It must have been a bitter moment for him. On 18 August he acknowledged this reality explicitly when he wrote that the arrival of an RAN battle cruiser in 1913 had made any pre-war plans in Berlin for the squadron operating as commerce raiders on trade routes in the South West Pacific overly ambitious and dangerous. His well-known understatement written to his wife read: ‘The Anglo Australian Squadron has as its flagship Australia, which by itself, is an adversary so much stronger than our squadron that one is bound to avoid it.’

Invidious options for von Spee

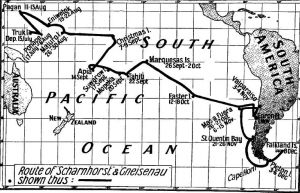

On 25 August Von Spee learned that the Japan had declared war on Germany. The powerful Japanese fleet now made the North West Pacific hostile. Tsingtao was about to be under siege from Japanese troops and was no longer an option for basing or supply. There remained only one course open to von Spee. He had to cross the vast Pacific, round the Horn and attempt to fight his way home against whatever the RAN and the RN could place in his path. He knew it was a dangerous, probably impossible option, and a logistical nightmare, but it was all he had left to offer his men and his Kaiser. As long as he could stay afloat and keep moving he was effectively a ‘fleet in being’ and could divert British naval resources that were needed elsewhere.

Changing Pacific priorities 1913 -14

The Admiralty’s pre-war plan for the Pacific formed part of its world-wide commerce protection effort. Consequently both Admirals Jerram and Patey believed that their first priority was to find and destroy enemy commerce raiding cruisers. But once the war started competing British and Australian government priorities emerged. These included the seizure of German Pacific territories and the silencing of their German wireless telegraphy stations. Churchill and Sturdee therefore changed their priority to the elimination of the WT stations and the seizure of the German colonies across the Pacific. The stated aim was to sever German communications which could aid German warships; the unstated intention was to use the territories as bargaining chips when the war ended. The Australian government was also keen to forestall the possible Japanese seizure of German colonies on Australia’s doorstep, particularly in New Guinea.4

The Samoan Operation – Taking the Kaiser’s Colony

In the event of war the New Zealand Government had volunteered to occupy German Samoa and take over the WT station in Apia. It was now asked to do so by both Churchill and the Secretary of State for War, Kitchener. Seizing Samoa was deemed to be: a great and urgent Imperial Service.5

On receiving Admiralty orders Patey assembled at Noumea an escort consisting of his flagship and cruisers, including the French cruiser Montcalm. He believed the threat to the New Zealand troop convoy from von Spee was real and he reasoned that if the German squadron was heading for Samoa, to defend the Kaiser’s colony, he could be brought to battle there. On the basis of the knowledge then available it is hard to fault the proposition that the Samoan expedition was the best chance of achieving a favourable encounter with the German ships.6It was a reasonable and prudent assumption and only a few weeks premature. Von Spee would head to Samoa in early September once he learned that it had been seized.

On route to Samoa Patey learnt that the Japanese had entered the war and he was more than ever convinced that von Spee had no choice but to head for South America where re-supply was guaranteed in nominally neutral, but de facto pro German, Chile. Patey reasoned that Von Spee’s way into the Indian Ocean was blocked by Jerram’s fleet and he would have no chance of getting coal supplies there. It would be a logistical trap from which his fuel-hungry coal fired heavy cruisers could not escape.

The German Governor of Samoa refused to formally surrender but wisely offered no resistance to the New Zealand force of 1500 volunteers who landed on 29 August 1914. Had Patey been permitted to stay at Apia, as he wished, to await von Spee, battle would have been almost inevitable. But the Admiralty, which was not keeping up with the Melbourne signal intelligence believed, without evidence, that von Spee was probably somewhere off northern China. They optimistically stated that his squadron was: being covered by Jerram. The scale of the Pacific was apparently unfamiliar to the Admiralty who appeared to be applying European frames of reference to the immensely greater distances of the Far East and Pacific.

Once the Samoan expedition had succeeded the Admiralty reinstated the delayed expedition to be mounted to capture the Bita Paka WT station near Rabaul and to occupy German New Guinea. When first asked his opinion of the New Guinea operation Patey told the Australian Naval Board that: wireless stations will have to wait for now. After the war Patey, wrote that his intention in going to Samoa was not only to cover the troop convoy but in the hope that: ‘I might have the opportunity of bringing Admiral von Spee to action, as I felt sure he would be in the vicinity, and I thought that once I had got so far east I might be left to free to deal with the German Squadron in my own way.’

This was overly optimistic. The WT revolution combined with older cable links meant that Patey, like all other flag officers at sea, could receive orders from Whitehall in a maximum of forty eight hours and became merely the executor of Admiralty orders. The era of independent command was over. The Admiralty became the de facto operational commander and the Australian Naval Board concurred in the decisions made in Whitehall. Unfortunately during the early years of the Admiralty War Room’s operations its limited staff discovered that it was much easier to assumecommand of world-wide naval operations than to actually try and conduct such operations from afar.7

The Australian Naval and Military Force – the Battle of Bita Paka

The original Admiralty order of 6 August now required Patey to escort the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) to Rabaul. It spoke of the removal of the WT station, but also tellingly re-stated that: all territories taken would at the conclusion of the war be at the disposal of the imperial government for purposes of an ultimate settlement. Churchill spoke of the colonies as: diplomatic hostages for the liberation of Belgium. Maritime strategy in the Pacific was being made subservient to theoretical post-war diplomacy. The admittedly difficult task of locating von Spee, which should have remained an urgent necessity, was now dropped in favour of the capture of another German wireless station whose usefulness to von Spee was at an end as he proceeded ever further to the East.8

The German Squadron ‘raids’ Apia in Samoa

Von Spee, having heard of New Zealand’s seizure of German Samoa, diverted from his easterly course, left his fleet train and sailed his warships south to the occupied colony. He arrived on 14 September hoping to surprise Patey. But Patey had left Apia on 31 August and Australia and the RAN cruisers were back in Rabaul harbour supporting the operation to take the Bita Paka WT station. Had Patey’s wish to remain at Apia been granted by the Admiralty we might now be discussing the Battle of Samoa, not the Battle of the Falklands, as being the decisive engagement fought by the German East Asia Squadron in 1914. Certainly von Spee and his men were keen to fight the Australians. They cleared for action before dawn and entered Apia Harbour to mount a surprise attack on whatever might be there. They hoped to find an anchored battle cruiser.8Instead, like Patey at Rabaul in August, they found the harbour frustratingly empty. Captain Pochhamer, the First Officer of the Gneisenau makes much of the general disappointment in the squadron that Australia was gone when the Germans arrived.However he also wrote more realistically that Australia’s 12 inch guns: inspired a certain respect.9

If Australia had been at Apia, and had the Germans achieved surprise at close range with their excellent gunnery an Australian victory is not certain. However the probability is that the duty patrolling cruiser and the New Zealand lookouts at the WT station would have provided Patey with the warning he needed to weigh anchor and proceed into battle at an advantageous range of his choosing. Under these circumstances the likelihood is that von Spee would have lost ships. Even if he had escaped destruction his ammunition supply for his main armament would have been too diminished to allow him to engage in battle again. His chance of getting back to his fleet train would have been low. In practice any encounter with the RAN off Samoa would have stopped von Spee’s progress across the Pacific. Once in Apia harbour Von Spee sensibly made no attempt to re take the German colony or to shell its WT station now being operated by New Zealand signallers. He knew his gunners were going to need every one of their irreplaceable shells when battle was eventually joined.

Emden calls the shots

On 19 September the Admiralty learned that Emdenwas sinking British ships in the Indian Ocean as and when she met them and sending their crews to India with accounts of their humane treatment. Battenberg up to this point had made his priority finding the German East Asia Squadron and bringing it to battle. But Churchill’s focus had already shifted to getting Australian and New Zealand troops to the Western Front. The Admiralty’s attention, and that of the British cabinet and Australian and New Zealand Governments, shifted to the pursuit of von Müller which imperilled this strategic objective. The urgent priority was now to assemble a powerful escort to get the NZEF and AIF Divisions from Wellington to Albany in Western Australia, and then to Egypt and potentially into the trenches in France to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force.

Understandably, the Australian and New Zealand Governments had no intention of sailing their troops across an ocean known to contain a daring German raider without a powerful covering force to guard them from a potentially catastrophic attack. Churchill overrode Battenberg’s objections to this shift of priority away from von Spee to von Müller. The First Sea Lord was forced to concur in Churchill’s view that getting the troops to the Mediterranean was: ‘so important that nothing except the certain prospect of fighting enemy ships should delay it’.10Jerram’s flagship Minotaur was sent to Wellington to escort the New Zealand troop transports across the Tasman and the Great Australian Bight to Albany. Patey was stripped of Sydney and Melbourne which with Minotaurand Ibukimade up the powerful convoy escort which finally sailed on 1 November after being delayed since mid September by Emden’s depredations in the Indian Ocean.Australiawas also briefly ordered to escort the troop convoy, and proceeded south on 15 September only for the orders to be cancelled two days later. Once again the Admiralty’s indecision wasted four more days of Patey’s movements.

When news of the disaster at Coronel reached Fisher in London he detached Minotaur, from the convoy and sent her to Capetown at her best speed. Fisher reasoned that it was not impossible that von Spee might cross the South Atlantic and appear off German South West Africa and seek refuge in the deep water harbour at Walvis Bay. From there he could attack the multitude of British ships using the Cape route.

Emden’s strategic achievement in the Indian Ocean

Von Spee had released Emden at von Müller’s request to engage in cruiser war in the Indian Ocean. Tactically he did that brilliantly, but strategically he did far more. He threatened all British trade in the Indian Ocean and diverted all available allied warships from their alternative task of pursuing the German East Asia Squadron. Von Spee commanded the only German naval force outside Europe still able to inflict a significant defeat on the Royal Navy, if luck and circumstanceswere right. Emden’s cruise was a distraction from this unresolved fact. Nine days after the Anzac TroopConvoy sailed, Emden’s nemesis overtook her in the shape of the convoy escort Sydneyat the Battle of the Cocos Island. By then von Müller’s job of holding the world’s attention while von Spee proceeded unhindered was accomplished.

It is interesting to note that the perceived threat to the troops, who were to become the Anzacs, from Emden was real. After von Müller was captured he was asked by Sydney’s Captain John Glossop what he would have done if he had known of the convoy of thirty seven troop ships passing so close to Cocos Island. Müller said that Emden would have shadowed the convoy in darkness and at first light attacked troop transports with guns and torpedoes until he was out of ammunition or sunk by the escorts, which ever came first.

Von Spee’s Pacific progress to South America

While von Müller was attracting a massive hunt in the Indian Ocean his admiral was solving unprecedented logistical difficulties in getting to South America. Coal consumption was the over-riding concern and dictated a slow speed. Fresh food and water were also limited, and the German warships were not designed for steaming over such long distances.

After being frustrated at Samoa von Spee visited Bora Bora in the Society Islands. He flew no flags, and greeted the French Chief of Police in English. French colonists resupplied him with pigs and fruit and bread before an observant and literate native in a canoe pointed out the word Scharnhorst painted over on his stern. France apparently did not send her more observant police to the central Pacific. Von Spee paid the French, thanked them for their help and sailed on to Tahiti intending to seize the coal stocks he needed. A junior French naval officer, who knew from Samoa’s WT warning that von Spee was coming, set fire to the island’s coal supplies. Von Spee sank his French gunboat, silenced the boat’s disembarked battery that bravely fired on him, bombarded Papeete and burned the market before sailing away without coal and frustrated.11

A ‘Ruse of War’ and its consequences

Knowing he was being observed, von Spee sailed northwest over the horizon from Tahiti before resuming his easterly course. This elementary mariner’s ruse of war was later reported to the Admiralty who fell for it and concluded, without corroborating evidence, that von Spee was heading back into the north Pacific. As a result of this deception Cradock in his old ships at the Falklands would wait in vain for the armoured cruiser HMS Defence which he believed to have been sent to reinforce him from the Mediterranean. Defencewas not coming to his aid because it was now believed in the Admiralty that von Spee was not heading for Cape Horn and the South Atlantic. The Admiralty did not inform Cradock of this change of plan or the assumption on which it was based.

By October, on Admiralty orders, Patey in Australia was back at Fiji conducting pointless patrols, searching for the supposed return of the German East Asia Squadron to the western Pacific. Meanwhile through October von Spee made his slow progress via Easter Island – where he was willingly re-supplied from a British cattle farm manager who had not heard that a war had started – and on to Juan Fernandez. There he fuelled from colliers escorted to him from San Francisco by the light cruiser Leipzig. From there it was a short voyage to the ports of Chile and the snow capped Andes. But before his welcome in Valpariso would come his victory at Coronel.

HMAS Australia and Patey – a dog tethered to its kennel

While this laborious trans-Pacific progress was occurring, Patey continued to patrol off Fiji, and it would not be until 8 November, a week after Coronel had been fought and lost, and Fisher was back at the helm, that the Admiralty ordered Australiato sail to South America. For nearly two months Patey had been in a state of impotence described by Arthur Jose, the Official Australian War historian, as being ‘like a dog tethered to his kennel.’

Hindsight is a wonderful asset and it is easy to be wise about what should have been done with its assistance. But two contemporary naval strategists who were in the midst of these events and who deplored what they saw, cannot be lightly dismissed. Admiral Jerram, observing events, lamented what he called: blundering about in the Pacific achieving nothing. He wrote to his wife: ‘The Australian Squadron, were within about 1,200 miles of the German cruisers and by Admiralty order footling about with expeditions to New Guinea and Samoa, operations which could not possibly have any effect on the outcome of the war and which might have been undertaken at any slack time later on. Absolutely contrary to all principles of Naval Warfare, as in the first place, they were extremely dangerous due to the near presence of a powerful cruiser force and, in the second, they gave time for the enemy to collect coal store etc.12

Commander Hugh Thring, who had prepared the RAN war book and was the most experienced Pacific planner and maritime strategist in Australia, called the Samoan Expedition ‘futile and a waste of precious weeks.’ With the benefit of hindsight it is hard to disagree with the opinions of these two contemporary strategists.

What might have been had HMAS Australia joined Cradock

An alternative possibility for HMAS Australia’s deployment could have been considered. It would have required more knowledge, and also more strategic imagination, than was available in the Admiralty or in the Australian government. However if at the beginning of September, instead of returning to New Guinea from Samoa, Patey had been supplied with a fast collier and high quality Westport coal from New Zealand to increase his range and endurance Australia, perhaps accompanied by either Sydneyor Melbourne, might have joined Cradock at the Falklands before von Spee arrived at Coronel. The RAN ships could have taken the southerly great circle route into high latitudes round the Horn to minimise the distance into the South Atlantic. One can only imagine the relief that Cradock and his sailors would have felt as the tall masts and powerful turrets of the Australian battle cruiser became visible from Sapper Hill above Port Stanley in late October. Alternatively, they could have travelled a shorter distance and met Cradock’s ships off Chile and together waited for von Spee’s inevitable arrival in the waters off Valparaiso.

It was not to be and on 4 November Churchill, who had ordered Patey to remain in Suva, would ask where exactly HMAS Australia was. The answer was that she was where she had been ordered to remain by the Admiralty in mid Pacific, doing nothing useful. Like Jerram sent pointlessly to Hong Kong in August when he wanted to be dealing with Emden and von Spee’s fleet train in Tsingtao, Patey had been played out of the game by the Admiralty. The opportunity to bring von Spee to battle had been frittered away. The Royal Navy had been defeated at sea, The British public were appalled and were demanding accountability and revenge.

Fisher now took charge and ordered a reluctant Jellicoe to detach Australia’s two half sisters, Invincibleand Inflexible, from Rosyth to take their revenge on von Spee. Churchill had to be convinced by Fisher to send two battle cruisers, not just one to the South Atlantic.

Fisher ordered Patey to take Australia and block the Pacific side of the Panama Canal in case von Spee had plans to go north and use it to return to Europe. With the old Sea Lord back in charge serious strategic thought was being given to all logical possibilities in the Pacific.

HMAS Australia after Coronel – the nearest point of contact

After the Battle of the Falklands and the destruction of the German Squadron by Inflexible and Invincible, Australia was ordered to sail to the United Kingdom via Cape Horn. As the flagship steamed through the waters off the Falklands, where Fisher’s other two greyhounds had avenged Cradock, Australia stopped to pick up a souvenir of the battle spotted by the officer of the watch. It was a lifebuoy with the word Scharnhorst on it. It was taken to Patey to examine. That lifebuoy was the closest that Fisher’s antipodean greyhound, HMAS Australia got to the enemy that she had been designed to counter in the Pacific and bring to battle. Admiral Patey and his ship’s company must have been above the wrecks of the East Asia Squadron’s ships containing the bodies of Vice Admiral Maximillian von Spee, his two sons, and nearly 2,200 German sailors. These men had joined RearAdmiral ChristopherCradock and his 1,600 Royal Navy sailors on the sea bed of the southern ocean.

Footnotes:

- Jerram Private Papers, letter to wife Clara, Nov 1914, GB 00064, quoted in Carlton. M., First Victory 1914 p 83.

- Hohenzollern-Emden, Prince Franz Joseph, Emden: The Last Cruise of the Chivalrous Raider, 1914 p 32

- Navy Office in Melbourne had the German merchant marine codebook but not the naval codes von Spee was using. This was useful but not definitive intelligence.

- The Australian view of the Anglo Japanese alliance was very different from that of the Imperial government. Before the Battle of Tsushima Australians viewed Japan with suspicion. After that first victory at sea for an Asian power against a European, Australians viewed the Japanese navy with alarm.

- Samoa could have been occupied at any time, with relative ease, after the destruction of the German East Asia Squadron. It was of no particular strategic significance as there was no coal stockpiled there. Von Spee would have had no logical reason for using Apia as a base, as it was well away from the main shipping lanes which would have justified his operating from there as a commerce raider.

- Stevens, D. The RAN in World War 1, p 45

- Lambert, N. pp 385 – 387

- Bita Paka WT station was duly taken on 11 September with the loss of one RN officer, five Australian sailors, an Australian Army doctor, one German regular and approximately thirty native German irregular police.

- Pochhammer, Hans. Before Jutland: Admiral von Spee’s Last Voyage.

- Stevens and Reeve, p 255.

- The French navy court martialled the officer in Toulon for losing his gun boat before later decorating him posthumously for his bravery.

- Jerram Private Papers, GB 0064 JRM, quoted in Carlton p 171

Bibliography:

Bean, C. E.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18.University of Queensland, 1921

Carlton, Mike. First Victory 1914- HMAS Sydney’s Hunt for The German Raider Emden.William Heineman Australia, 2013

Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis, 1911 -1918. Odhams Press, London 1938

Corbett, Sir Julian S. Naval Operations, Vol. 1, Longmans, Green & Co. London 1920

Gilbert, Gregory. Steaming to War: HMAS Australia (I) in August 1914– AWM Wartime Magazine 2014

Hohenzollern-Emden, Prince Franz Joseph. Emden: The Last Cruise of the Chivalrous Raider, 1914. Lyon Publishing International, London 1989.

Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel: Britain Germany and the winning of the Great War at Sea.Random House, 2003

Overlack, Peter. The Commander in Crisis. Graf Spee and the German East Asian Cruiser Squadron in 1914. In: J. Reeve & D. Stevens (Eds) The Face of Naval Battle. The human Experience of Modern War at Sea.Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003

Pochhammer, Kapitan zur See Hans. Before Jutland: Admiral von Spee’s Last Voyage. Jarrolds, London, 1931

Stevens D and Reeve J. Southern Trident. Strategy, History and the Rise of Australian Naval Power. Sydney, Allen and Unwin 2001

Stevens, D. From Offspring to Independence, in Dreadnought to Daring. Seaforth 2012

Stevens, D. The RAN in World War 1, 2014(unpublished manuscript pages 44-45)

The Australians at Rabaul. Vol. X

The Royal Australian Navy 1914-1918. Vol. IX

The Story of Anzac. Vol. I