- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Rushcutter

- Publication

- March 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Java is heaven, Burma is hell but you never come back alive from New Guinea – Japanese wartime saying

An eagle-eyed member of our Society drew attention to this short news story appearing in his local paper, the Northern Territory News, dated 3 November 2016.

News that the historic Rushcutter may be left to rot on the bottom of Darwin harbour is saddening to say the least. The boat, formerly known as HDML 1321, is an integral part of not just the Territory’s past but the nation’s. Its history is remarkable. Built with Huon pine before the Second World War [she was built in 1943 – Ed.], it played a crucial part in Australia’s battles with the Japanese.

It provided vital support for missions around New Guinea, including a mission which involved launching four folding kayaks with eight Z Special commandos into the Bismarck Sea. Documentaries have been made about the audacious mission and the HDML1321 played a key role. Ironically, it was also involved in a recent plot by alleged “wannabe” Australian terrorists to use it to get to Syria.

For years it worked as a harbour defence vessel in Sydney and was renamed the HMAS Rushcutter before being sold to private owners.

The boat’s links with the extreme sacrifice made by our army and navy deem it worthy to be held in pristine condition in a museum or the Australian War Memorial — not at the bottom of the ocean. The only thing keeping this boat from re-emerging is money. The owners need $50,000 to raise it but seem unable to pay that amount. They are asking the Port’s owners, Landbridge, to fork out for the salvage mission but the Australian War Memorial should also not stand idly by and let a piece of Australian history disappear.

In its time, the boat provided valuable reconnaissance information which helped save Australian lives. It is time to return the favour to this historic old boat and pull it from its watery grave.

Motor Launches and Harbour Defence Motor Launches

With the emergence of WWII the Royal Australian Navy was desperately short of patrol craft resulting in the introduction the British ‘Fairmile B’ Motor Launches (MLs). They were designed by car manufacturer and Royal Naval Volunteer Officer, Noel Macklin, who lived in Fairmile, near Cobham in Surrey.

Twenty launches were prefabricated in the United Kingdom for assembly at the Green Point shipyard on the Parramatta River. A further fifteen vessels were built by local boat-builders Lars Halvorsen at Ryde in Sydney and Norman Wright at Bulimba in Brisbane. These craft were augmented by a further twenty-eight similar but smaller vessels known as Harbour Defence Motor Launches (HDMLs). Most were supplied from American (16) and British (3) boat-builders and shipped as deck cargo, but nine boats were constructed in Australia by various local yards.

The first of the motor launches to arrive was HDML 1074 which had previously briefly seen service with the Royal Navy. She was shipped out in MV Port Auckland and commissioned into the RAN on 7 October 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Norman Grieve, RANVR. HDML 1074 and her two English sisters retained their RN pennant number while serving in the RAN. Grieve joined the RAN under the Dominion Yachtsman Scheme and after initial training in England was posted to the 6th Motor Launch Flotilla serving against the enemy in the North Sea where he received a commendation for bravery. Because of his wartime experience he was brought back home to take command of the first RAN ship of this type.

In his memoir A Merciful Journeyyoung Sub Lieutenant Marsden Hordern, when at Brisbane in ML 814, provides an account of what life must have been like in these small vessels, he wrote:

One day HDML 1074 arrived from Port Moresby under the command of Lieutenant Norman Grieve, RANVR; she had seen hard service in New Guinea, had crossed the Coral Sea in bad weather, and was salt-stained, leaking badly, and everything below deck – dirty clothes, wet oilskins and bedding – smelt of sweat and mildew. Her crew – half-naked, with flowing unkempt hair and beards – looked like a bunch of pirates. To my impressionable eye they had an enviable buccaneering aura, and from that time I cherished a vision of achieving such a swashbuckling image.

Marsden Hordern, one of the few remaining stalwarts from this era, went on to have a successful career in command of ML 1347, says he was in awe of the older and experienced Norman Grieve, whom he later came to know quite well. MLs were small and uncomfortable, where even hardened sailors could not always avoid sea sickness. In rough weather cooking was impossible and working in the engine room almost unbearable. Despite all these hardships they were well built, and when well led, their young crews were generally a happy bunch with pride in their small ships.

The first motor launch to be constructed in Australia was HDML 1321 (she also had the distinction of being the last in RAN service) which was built largely of Huon pine by Purdon & Featherstone in Hobart. She was laid down on 24 July 1942 and commissioned on 11 November 1943 under the command of the now experienced Lieutenant Norman Grieve, RANVR. His First Lieutenant in his new command was Sub Lieutenant Ambrose E (Ernie) Palmer, RANVR.

After commissioning, HDML 1321 proceeded to Williamstown, Victoria, before continuing passage via Sydney, Brisbane and Townsville to Milne Bay, New Guinea, arriving there on 1 February 1944. Here she was placed under the operational control of the Supervising Intelligence Officer North Eastern Area with orders to conduct special wireless telegraphy intelligence work and support Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) personnel and Australian Coastwatchers operating behind enemy lines. The vessel had been especially modified for clandestine work and her appearance was visibly different to others of her class. The most striking feature was her bridge superstructure which was extended aft, making her look more like an island trader.

Shortly after arriving in New Guinea Lieutenant Grieve was posted ashore and Palmer assumed command of 1321. Ernie Palmer, now promoted Lieutenant, would not disappoint. The son of an ‘old soldier’ turned planter in the Solomon Islands, he had a wealth of local knowledge and had established himself as a trader, recruiter and diver. On first enlisting for wartime service Palmer had joined the Army and had served as a commando in small ships before transferring to the RAN. Sub Lieutenant Russel Smith joined as the First Lieutenant and his reflections provide an insight into his commanding officer and the nature of work involved:

Our captain was one of our country’s unsung heroes. He was totally fearless, leading his young charges with marvellous wisdom and skill. The vessel was unique in that it had been seconded to the AIB and we were allocated the duty of servicing the famous coastwatchers, taking in their food and equipment, bringing out their sick and so on. To do this we operated the whole time amongst the occupied islands in enemy waters. The Japanese used powerful barges and they were a constant hazard as they were armed with a 20 mm twin-barrelled pom-pom on a two-man mounting and were very accurate and dangerous. To counter the enemy menace, and with the help of our American friends, we armed our vessel in an unorthodox way. We added two automatic 37 mm cannons plus four 0.5-inch heavy machine guns to back up our 40 mm Bofors, 20 mm Oerlikon and four rapid fire .303 machine guns.

Model maker and HDML aficionado, Roger Pearson, has been most helpful in providing background on these vessels.

The Guns of Muschu

Throughout 1944 HDML 1321 operated from Milne Bay and landed at isolated settlements on the Huon Peninsula between Lae and Madang. In April 1945, Z-Special Unit used 1321 in a mission, codenamed Operation COPPER. At Aitape she embarked eight operatives and their four Folboats (folding kayaks), taking them into enemy territory for a night landing on the island of Muschu near enemy-occupied Wewak. Muschu and Kairiru are adjacent islands lying off Cape Wom to the north of Wewak. Kairiru, the larger island, extends about 13 kms from east to west and 5 kms from north to south; it is mountainous with fertile volcanic soil. Its smaller sister Muschu is relatively flat and with many swamps is less fertile.

There were reports of two 140 mm (5.5-inch) naval guns on Muschu Island which had sufficient range to compromise planned Allied landings for the invasion of Wewak. The purpose of the mission was therefore to carry out reconnaissance of enemy strength on the islands, identify gun positions and, if possible, take a prisoner for further interrogation. Muschu and Kairiru were occupied by the Japanese in January 1942. St John’s Mission on Kairiru was requisitioned as naval headquarters with a nearby seaplane base, submarine and barge depot; at its peak it was occupied by 3,000 mainly naval personnel. In March 1944 the headquarters was severely damaged by American bombing. Caves, and many tunnels which were excavated, provided shelter from bombing attacks.

Japanese forces operating out of Wewak were able to maintain supplies by using barges. This traffic was harassed by USN PT Boats, which in turn were attacked by enemy gun positions on Kairiru where it was believed there were at least two 75 mm gun batteries. These had been subjected to American bombing and bombardment by RAN ships, seemingly without success.

The insertion took place on the night of 11 April but it did not go according to plan. Although the eight operatives were successfully disembarked from 1321, their boats were swept south by strong currents. Three of the Folboats capsized after being caught in a shore break, losing a radio, two Sten-guns and a paddle. In spite of this setback, the group made it ashore, setting out immersed equipment – including their remaining radios – to dry, and then resting before continuing their mission. The following morning they encountered numerous unmanned defensive positions, including several heavy machine-guns which they dismantled and tossed into the sea. They then struck inland encountering a lone enemy soldier who was successfully captured, bound and gagged.

Although the Australian’s fortunes appeared to have changed for the better, the return trek to their temporary base camp proved otherwise. A wrong turn was taken and a Japanese patrol sighted. Taking cover in the jungle the patrol passed by but their captive was able to remove his gag calling out to his countrymen. The Z Unit were then forced to shoot their prisoner and engage the advancing enemy before breaking contact and retreating into the jungle.

After regrouping and resting for a period they made their way back to their temporary base but observed the enemy waiting in ambush. A Japanese patrol had found the lost paddle washed ashore and were alerted to the landing of Australian commandos. After an intensive search the Folboats, hidden in undergrowth, were discovered, and then an ambush was set for the returning commandos.

At night the unit moved to a cliff overlooking the pre-determined rendezvous point for recovery by 1321. Without radios and their torches unusable (they were not waterproof and had been soaked on landing), they were unable to signal 1321 which frustratingly could be clearly heard cruising close inshore. In later testimony Lieutenant Palmer says they returned to the rendezvous for the next five nights searching for the commandos but with no evidence of survivors 1321 was ordered to return to base.

The Log Rafts

At daybreak the survivors decided to construct a log raft with which they hoped would be sighted by the searching 1321 or reconnaissance aircraft. That night all eight men put to sea in their crude craft. Again they were caught in steep surf and the raft broke up, with all eight men being swept back ashore. All except one lost their weapons and packs. With the situation now becoming desperate a vote was taken on the best plan of escape. Four voted to try again but this time using individual logs, while the other four decided to go to the western end of the island, the shortest distance from the mainland, and attempt to swim the strait.

More recent computer generated calculations of the tidal drift for the period in question indicates that those on rafts may have been swept towards nearby Kairiru Island. After enlisting the help of ‘Missing in Action Australia’ a private expedition was organised to Kairiru in July 2010 by the late LTCOL Jim Bourke, AM, MG. From this expedition the fate of the men was determined and the location of two bodies found. The Australian Government War Casualties Unit then exhumed the remains of two men, which with the aid of forensic evidence and documentation in Government archives, indentified these as Corporal Spencer Walklate and Private Ronald Eagleton. The two were alive when washed ashore where they were captured and beheaded. Their remains were finally laid to rest with full military honours at the Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery on 16 June 2014. Their old comrade Mick Dennis attended this service and nearly a year later, on 09 November 2015 at age 96, this grand old veteran died peacefully in his sleep.

The other two on log rafts, Lieutenants Alan Gubbay and Thomas Barnes were believed to have drowned and their bodies later washed ashore on Kairiru Island. These were found by natives and buried. The Bourke expedition, after questioning locals, determined that the bodies had been removed by an Australian Army unit in June 1946 and were buried in the Lae War Cemetery as ‘Soldiers known only to God’. They were later identified by DNA analysis and their graves marked accordingly.

The Swimmers

On 14 April the remaining four men set out on foot, returning to their equipment cache where a radio was retrieved. They then headed for higher ground to set up the radio and hopefully make contact with the HDML. When approaching bomb craters where fresh water might be found, they ran into a Japanese patrol. In an exchange of fire two Japanese and three Australians (Sergeant Malcolm Weber and Signallers Michael Hagger and John Chandler) were killed. Sapper Edgar Thomas (Mick) Dennis then escaped into the jungle. Alone, he continued on to Cape Samein killing another enemy soldier and destroying a heavy machine-gun on the way. After dusk on 17 April Dennis, who was a champion swimmer and wrestler (his sister Clare Dennis was an Olympic gold medallist swimmer), put to sea on a self made improvised surf board and drifted and swam for about ten hours to the mainland, some 5 km distant, landing in darkness at about 0400 the following morning. He was recovered by a patrol on the banks of the Hawain River on the afternoon of 20 April, nearly ten days after the initial insertion. In recognition of his actions, Dennis was later awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the field.

With news of Dennis’s survival two other MLs, 804 and 427,were immediately dispatched to search for any other survivors who may have escaped from Muschu, but this proved fruitless.

Sapper Mick Dennis wrote of his experiences in a diary which eventually passed to his nephew, Don Dennis, a retired Australian Army officer who had served in Vietnam. From this and interviews with his uncle, Don Dennis wrote of these events in The Guns of Muschu, published in 2006. Don Dennis has been most helpful in vetting much of the material used in this article.

The Naval Unit that Vanished in the Jungle

In January 1942 a young Japanese doctor who had just graduated was enlisted into the Imperial Japanese Navy as a Surgeon Sub Lieutenant. His name was Tetsuo Watanabe and luckily for posterity he also maintained a diary, and even more remarkably, because of his wartime experiences, this document survived. Many years later in 1982 this small volume was published in Japanese and, in 1995, was translated into English as The Naval Unit that Vanished in the Jungle. From this we are to gain a first-hand account of the Muschu venture, seen through Japanese eyes.

Watanabe was the last naval doctor to be posted to New Guinea, arriving from Rabaul by submarine I-181 in December 1943 at the Japanese base of Sio, strategically placed on the Huon Peninsula about half-way between Lae and Madang. He had been posted to the 82nd Naval Garrison which had landed in this area with 7,000 men in June 1942. His introduction was to a meeting of the headquarters group which was held in a cave. As the garrison was in danger of being cut off without the possibility of future supplies, he was told of the planned withdrawal from the area and, as they could not take sick or weak troops, his job was to select those fit enough for the trek northwards. On 23 December those of the 82nd Naval Garrison classified as fit were underway, traversing the inhospitable terrain of mountains, ravines, rain forests and swamps.

This was part of an overall push by the 18th Imperial Japanese Army to relocate to better positions further northward in New Guinea. Many died from starvation, disease and insanity, killing themselves or asking to be killed. They had to divide into small platoons to reduce the risk of further losses from constant air attacks. Exhausted, with depleted numbers, the survivors reached the relative safety of Madang on 18 February 1944, where they had their first decent meal in over two months. After recuperation the force was again on the move before Madang fell to the Allies in April and in early May they reached their next and final stronghold of Wewak1.

We were surprised to see a nice road made by the Army’s Road Construction Unit. But Wewak airfield on the left hand side was a frightful spectacle. It was totally destroyed by bombardment. Similarly countless remains of our ships were lying in the harbour. The night march of 30 kms was not so tiring, as it was cool and the road was good. We slept in native huts at Cape Wom.

When they had started off from Sio some four months earlier the Unit to which Tetsuo Watanabe was attached comprised 200 men. When they reached the end of their march at Cape Wom this was down to just three survivors – Lieutenant Kakiuchi, Petty Officer Wada and Dr Watanabe. The remainder, with thousands of others, had just vanished into the jungle. From Cape Wom they were transferred to a naval base on Kairiru Island lying a few miles offshore.

By this time Watanabe had developed severe malaria, jaundice and hepatitis and must have had some retinal detachment or haemorrhage in the right eye, as he lost sight in that eye. Watanabe was as well cared for by fellow surgeons as the circumstances permitted and gradually began to show signs of recovery. The Chief Surgeon at Kairiru requested Dr Watanabe’s return to Japan on the last submarine to call at the island on 27 May 1944, but this request was refused. Eventually, and now with one eye, Watanabe returned to his duties and again began treating patients.

In September 1944 the unit was moved and consolidated on the nearby Muschu Island. From here they could see American and Australian troops relaxing on the beach across the water on the mainland near Cape Wom. Although the Japanese on the islands were constantly bombed, their camouflaged and fortified camps were not located and no men were lost in these raids. With ever decreasing food supplies their greatest fear was dying of starvation.

There was only one case of direct contact between the opposing forces when eight Australians from Z Force landed on Muschu Island on 11 April 1945. In that operation (according to Japanese records) three Australians and three Japanese were killed and four other Australians drowned. Dr Watanabe treated the wounds of two injured Japanese soldiers who were shot during this incident, one of whom died and the other survived.

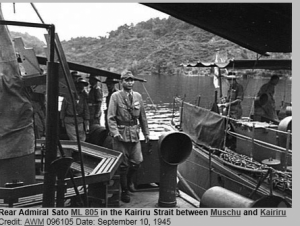

After news on 15 August 1945 that the Japanese Emperor had ordered the surrender of his forces and that the war was over, intelligence was received suggesting the garrison on Kairiru and Muschu Islands might be induced to surrender. Accordingly two RAN ships, MLs 805 and 809 circled these islands flying white flags from their mastheads and using a captured Japanese prisoner to broadcast surrender messages. This continued without results, and then suddenly on 17 August 1945, a small group of Japanese ventured onto a beach carrying a white flag. ML 805 lowered a boat with an Australian Army Intelligence Officer and an interpreter and a meeting was held on the beach. This was the first formal contact made during the war between Allied and Japanese forces in the South-West Pacific. As a result the Japanese garrison, comprising the 27th Naval Base Force, which was in radio contact with the overall commander of their forces on mainland New Guinea, Lieutenant General Adachi, was given permission to conclude a surrender agreement. On 10 September 1945 ML 805,with Major General Horace Robertson, Commander of the Australian 6th Division, embarked, proceeded to Kairiru Island where Rear Admiral Sato Shiro boarded and formally surrendered the approximately 800 mainly naval forces under his command on Muschu and Kairiru Islands.

Lieutenant General Hatazo Adachi later surrendered himself to the Australian command. He was flown to Wewak on 13 September 1945 where a formal surrender ceremony was conducted at Cape Wom after which he handed his sword to Major General Robertson. The surrender document was signed using the wardroom table taken from ML 805 which had been used for a similar purpose three days earlier. This historic table is now in the Australian War Memorial. Some fighting continued, as it took another two weeks for news to finally filter through to Japanese forces hiding in jungle retreats. MLs 805 and 809 were despatched to the Sepik River to advise natives and Japanese of the surrender. They proceeded on a remarkable feat of navigation, steaming 212 miles upstream encountering many Japanese living on friendly terms with villagers; many of the soldiers were sick and no resistance was offered.

After the surrender Muschu Island was used to detain Japanese POWs from the entire Wewak area. Many were sick and weak from disease. Of the estimated 11,000 to 12,000 prisoners held on the island less than 10,000 survived to return to Japan, but all survivors were repatriated by March 1946. In the Australian official war history it is estimated that more than 1,000 Japanese prisoners died during the march to, or on, Muschu Island because of malnutrition. This was not helped by a lack of food and medical supplies then available to both Australians and Japanese.

Marsden Hordern, then in command of ML 1347, visited Muschu Island a number of times when it was used as a prison camp as his ship was involved in ferrying POWs from the Sepik region to Muschu. He notes the Japanese had built a temporary hospital, a long thatched palm structure, with open sides built of local wood. Conditions in the hospital were horrific with many dead and dying, and burial parties constantly at work.

On 26 November 1945 the cruiser HMAS Shropshire was embarking Australian troops from Wewak for their return home. By coincidence on the same day, ML 1347 had the unusual task of leading the former Japanese cruiser Kashimato an anchorage off Muschu where she embarked 1,100 prisoners for return home. She made another voyage to Muschu on 8 January 1946, embarking an unspecified number of prisoners for a similar return to Japan. Kashima, which had been a flagship involved in the capture of New Guinea, was one of the few major Japanese naval ships afloat at the end of the war; with her armament removed she was converted into a transport and over the course of a year repatriated about 6,000 Japanese troops from around the Pacific to their homeland.

In 1969 a Japanese mission visited Kairiru Island and with the assistance of local people located and exhumed a large number of the remains of Japanese servicemen who had died here during and post WWII. The remains were cremated in accordance with Shinto faith ritual and the ashes returned to Japan. A small memorial was also built on the island.

A Canadian, Robert (Bob) Henderson, who lived in the Wewak area for three years, wrote of his interest in an article titled Beautiful Muschu Island – Japanese Hell. From stories told by locals he says Japanese POWs were left on the island with virtually no provisions; many perished before the survivors were repatriated some months later. He also notes that a landslide in 1976 revealed a cave where the remains of more Japanese were discovered. These remains were later cremated by Japanese authorities and the ashes returned to their homeland.

What next for HDML 1321

HDML1321 continued to serve in New Guinea throughout the remainder of 1945, punctuated by brief visits to Townsville and Brisbane. She was next lent to the Northern Territory Administration until 1951. Upon return to Sydney she was attached to the naval base HMAS Rushcutter, reclassified as a Seaward Defence Motor Launch (SDML 1321), used for RANR and Naval Cadet training. In common with other attached vessel in 1953 she assumed the name of her parent establishment, confusingly also becoming HMAS Rushcutter. She decommissioned in 1970 and in August 1971 was sold for $14,200 to private owners who converted her into a cruise launch named MV Rushcutter.

In 2006 Rushcutterwas purchased by the eccentric mother and daughter team of devoted maritime enthusiasts, Wendy and Tracey Geddes. They took her to Nhulunbuy, NT where she was painstakingly refurbished over three years at a cost of about $150,000 as a cruise and dive craft. In her new role she was based at Darwin.

A survey of the 73 year old vessel was carried out in early 2016 revealing the hull to be in excellent condition and the original two American-made six cylinder Buda-Lanova (later generations know these as Allis-Chalmers) diesel engines still functioning, although one was slightly down on power due to wear of the original cylinder liners.

Thinking of retirement, in 2016 the Geddes put their baby up for sale. In April a small group of prospective buyers travelled to Darwin to inspect the boat. Apparently these were ISIS sympathisers who were trying to find a suitable vessel to travel to the Middle East. As the Federal Police got wind of this the sale fell through.

Finally came the tragic accidental sinking of Rushcutter at her moorings in Darwin’s small boat anchorage on 19 October 2016. She was subsequently raised a month later on 20 November. Now needing much more love and attention which her owners cannot afford, her fate is uncertain. Would not this historic vessel, the last of her type in Australia, make an important contribution to a maritime museum?

In a Parliamentary speech on 22 November 2016, Luke Gosling, the Federal Member for Solomon (Darwin metropolitan area) addressed the need for the restoration of this important historic vessel. He thanked the Darwin Port Authority and Bhagwan Marine for helping refloat Rushcutter and for the assistance of the Paspaley Pearl Group in providing hard-standing for potential restoration. He also thanked local volunteers including Ambrose Palmer, son of her former captain.

Our latest information (February 2017) is that the Geddes family have generously sold HDML 1321 to a Darwin based committee ‘Save Motor Launch 1321 Inc.’ for the princely sum of $2. It should have been $1 but no one could produce a $1 coin at the time of the transaction. The committee, chaired by Vikki McLeod, who is an Army reservist engineer and on the board of the Darwin Military Museum (DMM), aims to carry out the difficult task of recovering and restoring the ship to her wartime condition and then putting her on display at the DMM.

Notes:

- There are difficulties in estimating the total number of Japanese forces fighting on the mainland of New Guinea over the period of the conflict. After the war Major General Kane Yoshiwara, General Adachi’s chief-of-staff, gave the maximum strength of the 18th IJA as 105,000, which had shrunk to 54,000 by March 1944. Many more perished during the final retreat towards Wewak, leaving about 13,000 at the time when General Adachi surrendered his forces. General Adachi, an honourable man who accepted responsibility, before taking his own life, wrote: “During the past three years operations more than 100,000 youthful and promising officers and men were lost and most died of malnutrition”.

References

Dennis, Don, Guns of Muschu –Eight Men went in – only one Returned. Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 2006.

Dexter, David, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Series One: Army, Volume VI – The New Guinea Offensive. Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1961.

Evans, Peter & Thompson, Richard (Eds.), Fairmile Ships of the Royal Australian Navy, Volumes I & II. Sydney, Australian Military History Publishers, 2005.

Gill, Hermon G., Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Series Two: Navy, Volume II – Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945. Canberra, Australian War Memorial, 1968.

Henderson, Robert, Beautiful Muschu Island – Japanese Hell, viewed 23 December 2016, http://www.writing.com/main/view_item/item_id/1573388-Beautiful-Muschu-Japanese-Hell.

History of HDML 1321, Seapower Centre, Canberra, viewed 08 December 2016, http://www.navy.gov.au/hdml-1321.

Hordern, Marsden, A Merciful Journey – Reflections of a World War II Patrol Boat Man. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press, 2005.

Johnston, Vanessa, Remembering the War in New Guinea– Summary of the Experiences of NavalSurgeon Tetsuo Watanabe.Canberra, Australian War Memorial, viewed 08 December 2016, http://ajrp.awm.gov.au/AJRP/remember.nsf.

Report of Proceedings HDML 1321 and ML 805 August/September 1945. Canberra, Australian War Memorial.

Watanabe, Tetsuo, The Naval Land Unit that Vanished in the Jungle, first published in Japanese 1982 with English translation by Hiromitsu Iwamoto. Canberra, Tabletop Press, 1995.

Watters, David, Stitches in Time– Two Centuries of Surgery in Papua New Guinea. Sydney, Alibris Corporation, 2011.

Worledge, G. Ron (Ed.), Contact – HMAS Rushcutter & Australia’s Submarine Hunters 1939-1946.Sydney, The Anti-Submarine Warfare Officers’ Association, 1994.