- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This paper by Mr C. G. Austin, Honorary Librarian, was read to The Historical Society of Queensland Inc. on Thursday 28 April 1949 and printed in the Journal of The Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Volume 4 Issue 2 (1949). It is now reproduced with the kind permission of the Society.

Mr President, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The title of my paper tonight is ‘The Early History of Somerset and Thursday Island’ for it is impossible to cover the whole of the history of Torres Strait in one night, so much history has been made in that area that a series of papers would be necessary to do justice to the subject. The early navigators, the shipwrecks in those dangerous seas, the pearling industry, and the Torres Strait Islanders deserve separate treatment. I have therefore limited this paper to the foundation of Somerset and the beginnings of Thursday Island.

Many famous navigators had passed through this area; Torres in 1606, Cook in 1770, Captain Bligh on his memorable voyage after the mutiny on the Bounty, the voyages of the Fly, Bramble and Rattlesnake. The first resident of Newstead House Captain Wickham, carried out his work as a marine surveyor in this area.

In the early part of the nineteenth century ships passing through Torres Strait encountered the double dangers of coral reefs and hostile natives. The massacre of the crew of the Charles Eaton, the stories of white women, such as Barbara Thompson, being captured by the natives of the Prince of Wales Island, drew attention to the need for some protection for shipwrecked mariners and those who passed through the Strait to the nearest port of refuge at Port Essington or Timor.

Depots for provisions for mariners in distress were established on Booby Island, west of Thursday Island. Booby Island was named by Captain Cook in 1770, and Bligh in the launch of the Bounty called there. When Bligh became Governor of New South Wales he petitioned the Home Government to form a depot at Booby Island where shipwrecked mariners could find succour in their distress, but it was not until 1824 that Bligh’s request was granted.

Earlier than this, the surgeon of the Pandora, in company with castaways which included some of the Bounty mutineers, declared that what was wanted in the vicinity of Cape York was a settlement. ‘Were a little colony settled here’, he wrote as he listened to what he called ‘wolves’ howling on Horn Island at night, ‘a concatenation of Christian settlements would enchain the world, and be useful to an unfortunate ship.’

The credit for establishing a settlement in the Cape York Peninsula must be given to Sir George Ferguson Bowen, the first Governor of Queensland. During the eight years of Sir George Bowen’s governorship, a line of new ports was opened all along the eastern coast of Queensland from Rockhampton to Cape York and also to the head of the Gulf of Carpentaria; and the pastoral settlers overspread the entire interior, this virtually adding to the British Empire a territory four times larger than the British Isles.

The opening-up of this territory was described very eloquently by Sir George Bowen when he said, ‘Such are the triumphs of peaceful progress; they are victories without injustice or bloodshed; they are conquests not over man, but over Nature; not for this generation only, but all posterity; not for England only, but for all mankind.’

Those of us who are accustomed to the vastness of Australia are apt to forget the huge area of Australia colonised in a short space of time. Our first Governor once pointed out that in the period 1845 to 1865 the English colonisation in Australia alone spread over a far greater space than the aggregate of all the Greek and Roman colonies put together.

The various considerations which pointed to the necessity of a station in the extreme north of Queensland were summed up in a dispatch from the Governor to the Duke of Newcastle on 9th December 1861 – two years after his arrival in Queensland.

‘In a naval and military point of view a post at or near Cape York would be most valuable, and its importance is daily increasing with the augmentation of the commerce passing by this route, especially since the establishment of a French colony and naval station at New Caledonia.

‘Your Grace will perceive from the enclosed Minute of Council, that the Government of Queensland will be willing to undertake the formation and management of a station at Cape York, and to support the civil establishment there. This cannot be considered as otherwise than liberal and reasonable and as strong proofs of the public spirit and of the attachment to the parent State, with which I have ever found the members of the Queensland Parliament to be animated. For the Colony, as such, has manifestly no direct or immediate interest in the foundation of a settlement at Cape York which is twelve hundred miles from Brisbane, that is further than Gibraltar is from London’.

The Home Government was fully prepared to entertain the proposals of the Queensland Government, and the Admiralty agreed that the Governor and the Commodore in command of the Australian Station should together proceed to Cape York. Accordingly, the Governor left Brisbane on 27 August 1862, in HMS Pioneer under the command of Commodore Burnett, for the purpose of selecting the most eligible site for the proposed settlement.

Pioneer made a remarkably good trip under canvas, reaching Booby Island in Torres Strait, the furthest limit of the north-west of the jurisdiction of Queensland, in thirteen days. There was deposited an iron case for the letters generally left on this rock by the passing ships of all nations, to be conveyed to their respective addressees by succeeding vessels.

The site ultimately chosen was at Port Albany, in the passage between the mainland and Albany Island. The settlement was named Somerset in acknowledgement of the readiness with which the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Duke of Somerset, had lent his aid to the undertaking. Portion of the settlement was to be set aside for the use of the Royal Navy. The site was selected on account of its geographical importance, as harbour of refuge, coaling station, and the channel through which trade of Torres Strait and the North Pacific was to pass.

Mr John Jardine, who was then Police Magistrate at Rockhampton, was appointed Government Resident and sent in 1863 to establish the new settlement. He decided on a site on the mainland opposite Albany Island.

Besides the uses pointed out by Sir George Bowen, Somerset was also to be a sanatorium for the people who were just then rushing to the Gulf country to take up land, and in this respect was to supersede the establishment on Sweer’s Island, east of Bentick Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria, near Burketown. About this time there had been a violent outbreak of yellow fever at Burketown, many perished, and the seat of government had been transferred from Burketown to Sweer’s Island.

The Queensland Government contributed £5,000 and the Imperial Government £7,000, besides sending a detachment of twenty-five marines under command of Lieutenant Pascoe, and accompanied by Dr. T. J. Haran as Medical Officer.

The official foundation of the settlement took place on 21 August 1864, when HMS Salamander visited it on behalf of the Imperial Government.

A report of the establishment of the settlement was published in a newspaper by J. O. Burgess, midshipman in Salamander. The ship was commissioned at Sheerness on 9 December 1863 by Commander the Hon. John Carnegie. She was a paddlewheel sloop of 818 tons, barque-rigged, and fitted with a roof and chart room for surveying purposes. After a long voyage of 147 days the ship reached Sydney, and later anchored at the mouth of the Brisbane River on 26 June 1864.

Accompanied by the barque Golden Eagle, which carried government stores, Salamander sailed on 14 July. The passage of the Inner Barrier before the days of lighthouses and buoys was intricate, and from Rockhampton Bay the navigation was chiefly done from the masthead during daylight, anchoring each evening about 6 o’clock until the arrival in Albany Pass on 29 July 1864.

On 1 August, Golden Eagle arrived, also the barque Woodlark, and the schooner Bluebell owned by Captain Edwards, who had established a beche-de-mer station at Frederick Point, the north-western cape of Albany Island. Its building comprised a stone curing house and a store.

Mr John Jardine, Police Magistrate, and Dr. T. J. Haran, Government Medical Officer, being duly installed it remained for the marines under Lieutenant Pascoe and the accompanying landsmen to set to work, clear the ground and erect buildings constructed in the south for what was to be the nucleus of the first settlement at Cape York.

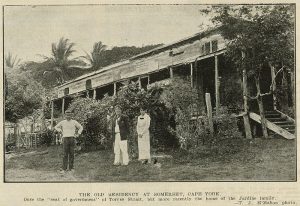

An early sketch of Somerset, drawn by Mr J. Jardine in 1866, shows a Government Residence, Police Quarters and Customs House on the eastern side of the inlet, and Barracks of Marines and Medical Superintendent’s House on the western side. Salamander also appears in the sketch, which is reproduced in The Jubilee History of Queensland, edited by E. J. T. Barton, and published by H. J. Diddams and Co. in 1909.

This area has always been full of surprises, and it is amusing to read that horses and sheep transported on the Golden Eagle were turned loose on Albany Island under the care of a gentle shepherd in the Royal Marine Light Infantry who within twenty-four hours of encampment was much startled by the curiosity of a seven-foot brown snake desirous of exploring his tent. The provisioning and protection of the new settlement was supplied by Salamander, and later HMS Virago, which ships made three trips per year from Sydney to Somerset for this purpose.

Epic droving trip

In 1864 two sons of John Jardine, Frank and Alick, organized and carried to a successful conclusion one of the finest droving trips in the annals of Queensland. It was realised that the new settlement was dependent on sea transport for supplies, and to provide food, a mob of cattle was driven from Rock-hampton to Somerset, up the peninsula in the face of hostile tribes. The party left Rockhampton on 14 May 1864, and reached Somerset on 2 March 1865, ten months later. It must be remembered that the Kennedy expedition, with its attendant tragedy, was made in 1848. Sixteen years later, the Jardine boys traversed the same ground – with success. An offer by the Government to promote funds to meet the cost of the expedition was not accepted as the Jardine family regarded the trip as a private business venture.

During the continuance of the settlement at Somerset several distinguished officers of Her Majesty’s Navy visited the place and contributed to the survey work in the Strait. The Hon. John Carnegie was succeeded in Salamander by Commander Duke Young. The last-mentioned officer was one of the few survivors of HMS Orpheus wrecked on Manuka Bar, New Zealand. The third Commander on the station was Sir George Nares (later Admiral Nares), noted for his Arctic exploration in command of HMS Alert. He also commanded Challenger on her voyage of deep-sea exploration in 1872-4. Other commanders in the Strait were Captain Bingham of Virago, and Commander (later Admiral) Moresby, whose ship the Basilisk was associated with much of the Commander’s valuable work in Torres Strait and on the coast of New Guinea.

The first land sale was held in March 1865. Sir George Bowen described this sale in a letter to the Right Honourable Edward Cardwell, MP, Secretary of State for the Colonies, on 17 April 1865.

‘In my letter to you by the last mail I mentioned that the first land sale at the new township named Cardwell was about to take place, and that speculators would be present from both Brisbane and Sydney. The upset price was twenty pounds per acre, but the competition was so active that all the lots were sold at an average price of 600 pounds per acre. In the same week took place also the first land sale at the new settlement at Cape York. There again the upset price was twenty pounds per acre, but the price realized averaged only 150 pounds per acre. This result means that the speculators in land consider that Cardwell, from its central position and other advantages, has four times a better chance than Somerset of becoming one day the capital of a new Colony.’ Subsequent events proved that the speculators were astray in their judgement.

When John Jardine took up his residence at Somerset, he occupied one of the loneliest positions in the history of Queensland. Normanton, in the Gulf of Carpentaria, and Cardwell were his nearest neighbours; he was restricted to sea transport, and on the Cape York peninsula were many hostile tribes. Somerset justified its establishment as a port of refuge, for the crews of three wrecked ships were able to receive succour there soon after its foundation.

John Jardine, the first Government Resident and Police Magistrate at Somerset, held office until the end of 1865 when he returned to his magisterial duties at Rockhampton. He was succeeded by Captain Henry G. Simpson, RN, who was still in office at the end of 1866. His appointment was for three years, but before the end of this time he left on sick leave and did not return.

The office was vacant at the end of 1867. The appointment was held by Frank Jardine in 1868 and 1869. In the latter year Frank Jardine was granted leave of absence, and H. M. Chester was appointed to succeed him. Frank Jardine again held office from 1871 to 1873, when he was succeeded by Capt. C. E. Beddome and later George Elphonstone Dalrymple. The next Resident was C. D’Oyley Aplin who had been Government Geologist for Southern Queensland in 1868-9. By a curious twist of fate, he had been on the brig Freak when she searched for members of the Kennedy expedition left at the Pascoe River. The remains of two of the party, Wall and Niblet, having been recovered, were interred at Albany Island, D’Oyley Aplin reading the funeral service. Frank Jardine again temporarily held office until the appointment in 1875 of H. M. Chester, who had held the office previously. H. M. Chester was the last Police Magistrate at Somerset and the first Police Magistrate at Thursday Island for in 1877 he was appointed to that office on Thursday Island.

The part played by the Jardine family in the history of Cape York and Torres Strait is recorded and universally applauded as the work of a family outstanding in the Torres Straits area. The part played by H. M. Chester is not so well known. Spencer Browne in his book A Journalist’s Memories describes Chester as ‘a great administrator, a man of extraordinary courage, and who sturdily and worthily, and without any littleness upheld the dignity of the law in that far-flung outpost’. The unpublished autobiography of H. M. Chester was kindly made available by his son, Mr C. L. Chester, of Toowong, and from this information some idea of this outstanding man can be formed.

Henry Majoribanks Chester was born in 1832, the son of the curate of Cripplegate Parish Church, London, the youngest of twenty children. He was nominated to Christ’s Hospital (The Blue Coat School) in 1840 and then attended the London School in Newgate Street, and later the Royal Mathematical School founded by King Charles II, in which boys were trained in the art of navigation as a preliminary to a career at sea. Boys at this school were presented at Court and H. M. Chester was presented at the time his uncle, Sir Robert Chester, was Master of Ceremonies. This uncle was later killed at the siege of Delhi, and the report of the siege records that ‘…he was killed by a round shot from the city, his body falling into the arms of the late Sir Henry Wylie Norman, then a young officer, afterwards Governor of Queensland’. In 1849 Chester was appointed a midshipman in the Indian Navy in which he served eleven years, and performed distinguished service in the Persian War.

‘It would be murder!’

About 1860 occurred an amusing episode with a crack French duellist. This Frenchman had a reputation for duelling which made him a dangerous opponent. Chester arranged an affront, and was duly challenged, but Chester was entitled to select the weapon. Accordingly, he sent his seconds to the Frenchman bearing an envelope in which was a description of the weapon selected. The Frenchman was horrified on opening the envelope to see a drawing of a butcher’s cleaver. H. M. Chester was a very powerful man and the finesse of the swordsman would not counter the strength of Chester. The Frenchman exclaimed to the Englishman, ‘But it would be murder!’ The Englishman politely informed him that it would likewise be murder if Chester had selected swords. Before long the Frenchman hurriedly left town.

When the Indian Navy was abolished in 1862, Chester eventually came to Australia and in 1865 entered the service of the Union Bank of Australia Ltd. at Brisbane. In December of the same year Chester relinquished his position in the Union Bank to enter government service and take up the position of Commissioner of Crown Lands and Police Magistrate in the Warrego district, and there surveyed a township at Charleville and Cunnamulla. In 1868 he was appointed Land Agent for Gladstone and served there and at Gympie for about nine months.

Appointment of H. M. Chester

In 1869, Frank L. Jardine, Police Magistrate at Somerset, applied for leave of absence and Chester was appointed to succeed him. In his autobiography we read: ‘On arrival at Somerset I found the garrison to consist of a sergeant and four town police constables, with five native troopers. One of the constables, a married man, looked after the troopers and lived on the southern hill. There were seventeen horses and a mob of about a hundred cattle running in the bush.

‘Jardine remained for a week and showed me over the Settlement. He impressed on me never on any account to leave the house without carrying a revolver even if only going as far as the stockyard and cautioned me, in the event of a night attack by the aborigines, never to stand upright on the verandah where the aborigines could see me but to go on my hands and knees, the better to see them’.

Chester was left to guard the settlement with six Europeans and three aboriginal troopers, while Cardwell on one side and Normanton on the other were the nearest towns from which assistance could be obtained.

One instance of the difficulties of transport is shown in Jardine’s trip back to Brisbane. Jardine left in the schooner that brought Chester to Somerset and Captain Hannah attempted to beat down the coast against the South-East trade winds, but after nearly three weeks had to give it up and run back before the wind to Somerset, whence they sailed round Cape Leeuwin, and it was nearly three months before they reached Brisbane.

Chester never had much regard for town police as sailors, and one of his first acts was to ask the Colonial Secretary to replace the town police with water police. The main menace to the Settlement was an attack by the Yardargan tribe, who occupied the country about twenty-five miles south of the Settlement and who could put 400 young men into the field. Fortunately, a small tribe of 120, who occupied the district round Somerset, feared the Yardargans and always advised the Settlement when the Yardargans were preparing to attack.

There were very few pearl-shelling stations in Torres Strait at that time, and Somerset being a fine port, the shellers who were all from Sydney got their supplies duty free. They employed aboriginals and Kanakas, and although wages, except to divers, were low, pearl shell was worth £200 per ton. Tortoiseshell was plentiful and a few sticks of tobacco would purchase a pound of it.

In October 1869, the Gudang tribe, who inhabited the Cape York district, reported that a cutter had been captured by the natives of Prince of Wales Island, who had killed the captain and his crew of Malays and carried off the wife and son of Captain Gascoigne, who were living with the islanders. A search of the island revealed the wreck with part of the body of a boy pierced by an iron barbed arrow. Chester applied for assistance, and on 1 April 1870, when the frigate Blanche(Captain Montgomerie) arrived bringing stores, five water police to replace the town police and five additional native troopers, Chester was annoyed to discover that these native troopers were released prisoners from St. Helena gaol, who had served half of a sentence of ten years for attempted rape and robbery under arms. Chester was never one to mince his words and he wrote to Mr Gray, the Under Colonial Secretary, to the effect that, if the Government chose to make him keeper of a convict prisoner they need scarcely enquire what became of the convicts for as there were eight native police and only six Europeans (four of whom had their wives and children with them) to guard the Settlement, some of the convicts would not return should they become mutinous. Blanche left on a punitive expedition against the perpetrators of the outrage on the crew of the cutter. The Mt. Ernest natives were thought responsible and this proved correct, for plunder from the ship was found in their gunyahs, such as the ship’s log book, etc. Three of the Mt. Ernest chiefs who were pointed out by the Cape York aborigines as the perpetrators of the massacre were shot.

New Guinea expeditions

Chester made many expeditions to New Guinea in the 1870s. On one trip he travelled up the Fly River and had a skirmish with New Guinea natives, who tried to attack the ship from their canoes. The expedition proceeded upstream and on the return journey Chester halted at the spot where the skirmish had occurred. He went ashore despite hostile natives and entered the chief’s hut and commenced to palaver. Before he left, all signs of hostility had disappeared.

The crowning event in Chester’s life was the annexation of New Guinea. He left Thursday Island on 24 March 1883, taking with him three water police and two men from the pilot cutter. On 4 April 1883, under instructions from Sir Thomas McIlwraith, Premier of Queensland, Chester took formal possession in the name of the Queensland Government, of all that portion of New Guinea and the islands adjacent thereto lying between the 141st and 155th meridians of east longitude. This was that portion not occupied by the Dutch. The formalities were performed at Port Moresby, the honour of hoisting the flag on this memorable occasion falling to Tom Crispin. Immediately the news was released there was much consternation in Germany for the Germans, as well as the Dutch, were interested in New Guinea.

The matter was soon raised in the British House of Commons and the London Times in a leading article deprecated that all Australian Colonies were not sharing in the administration of New Guinea.

Lord Derby, with diplomatic adroitness, later announced that he had decided to relieve Queensland of the responsibility of the annexation of New Guinea, and determined to make it an Imperial act. Eventually, on 06 November 1884, a British Protectorate was established over the South-Eastern portion of New Guinea.

The main reason for the transfer from Somerset to Thursday Island was that the anchorage in Albany Passage was regarded as very troublesome and even dangerous for large mail steamers – with the tide sweeping through as it does they often had to hold on by both anchors – while Port Kennedy was a safe harbor.

There was another reason in that the maritime boundary of Queensland was about to be extended so as to include all the islands between the coast and the Barrier Reef. Up to this time, fugitives from Queensland law were out of the jurisdiction of the State, if they were living on these islands. This extension of the Queensland boundary was provided under The Queensland Coast Islands Bill of 1879.

Mr H. M. Chester was appointed Police Magistrate at Thursday Island, with the subsidiary offices of sub-collector of customs and harbor-master, on 20 July 1877. Mr Allan Wilkie was appointed pilot on 14 September of the same year. The first reference in Pugh’s Almanac to Thursday Island as a settlement is contained in the information for the year 1884. Mr Chester was still Police Magistrate, Mr F. G. Symes sub-collector of customs, and Mr D. Cullen Postmaster.

Pugh’s Almanac

‘The E. and A. Coy. make this their first port of call and have a fine hulk – The Belle of the Esk – as their receiving ship where there is always a plentiful supply of coal. The Tinganini or Gunga take all the Normanton cargo from here. There are two hotels, the Torres Strait (Cockburn) and the Thursday Island (Mr T. McNulty)’.

In the early eighties communication with Brisbane was by the steamer Corea (Captain James Lawrie) of the Q.S.S. Coy. Ltd. She made monthly trips, taking supplies to the various pearling stations and bringing back pearl shell on the return trip. The pearling stations, or shelling stations, were located on the various islands round Thursday Island, and each station had a smart little fore-and-aft schooner yacht of from thirty to fifty tons register to transport the shell from the stations and carry the provisions back.

In 1882 a new very rich patch of shell was discovered west of Torres Strait, on what was locally known as the ‘Old Ground’. The water was comparatively shallow, being from six to ten fathoms in depth.

Progressive shellers made haste to increase their fleet. One, Mr James Clark, purchased in Brisbane the oyster cutter Amy. This vessel left Brisbane for Thursday Island in September 1882, with a crew consisting of Messrs. John Tolman, Wm. Wilson, and P. P. Outridge.

The first marine produce brought from this area was not pearl shell, but beche-de-mer, also known as trepang. It will be remembered that at the time of the foundation of Somerset in 1864, a beche-de-mer station was already established at Albany Island owned by Captain Edwards. Trepang is somewhat like a large sized eel, of many colours, and has always been popular in the Chinese market. Beche-de-mer was found on the reefs from Cape York southwards, and was also prolific on the Warrior Reef.

Beche-de-mer is responsible for changing the character of the inhabitants of the northern coast of Australia. For centuries Malay proas from the Dutch Indies have visited the coast as far east as the Gulf of Carpentaria. In February 1803, Lieut. Matthew Flinders in the Endeavour met six Malay proas beche-de-mer fishing near the western entrance to the Gulf of Carpentaria, part of a fleet of sixty sailing from Celebes. They took the catch to Timor for sale to Chinese traders. This fleet was accustomed to come down annually in the north-west season, returning after the south-east change, and continued to do so up to the 1890s. Then the South Australian Customs intervened to collect export duties and the regular trade ceased.

The Malay visits had a distinct effect on the aboriginal natives for along the Northern Territory coast the natives understand the Malay language and have adopted some of the Malay customs. This influence spread to the Gulf of Carpentaria for the present Bishop of Carpentaria related how on one occasion he landed near Groote Eylandt, and met aboriginals who had not been in touch with missionaries. These natives could not understand the language spoken by his Torres Strait boys but understood quite well the language spoken by his Malay boys.

One body which exercised a great influence in this area was the London Missionary Society. As early as 1871 the first missionaries, Messrs. A. W. Murray and S. McFarlane, arrived at Somerset to commence their work in the area. Murray remained two years and McFarlane returned to the Strait in 1874 and remained sixteen years. The Rev. W. Wyatt Gill arrived in this area in 1872. The well-known James Chalmers joined the Mission in 1877, but his main field of work was New Guinea. In 1877 McFarlane moved to Ma (Murray Island) and in 1879 established a school there. He secured the services of Robert Bruce for the school under whose direction several houses were built. The opening of the telegraph line to Cape York was a step forward in the development of Cape York. The credit must go to John Richard Bradford, who in 1883 led the preliminary exploration party from Cooktown to Cape York to select the route for the telegraph line. The party consisted of Bradford, William Healy as second-in-charge, Messrs. J. Cook, W. MacNamara, J. Wilson, Jimmy Sam Goon (a Chinaman) and Jacky, an aboriginal. The party left on 06 June 1883, and on 29 August Bradford and Healy, leading their horses, walked into Somerset, and were hospitably received by Frank Jardine.

The Society is fortunate in having in its possession a copy of the first issue of The Torres Straits Pilot published on 02 January 1888. This copy is on silk, and was donated by Mr Jack McNulty, well known to anyone who has lived on Thursday Island.

The Society also has in its possession a copy of The Torres Straits Pilot published on 27 January 1942. This edition recorded the immediate evacuation of the civilian population from the area for war purposes.

The Torres Divisional Board is first recorded in Pugh’s Almanac at the beginning of 1886. The members are given as Captain W. T. Boore, Vivian R. Bowden and Henry F. Houghton. The auditors were Thomas Braidwood and Alex. Stewart. The next year records Captain W. T. Boore as chairman, and members Vivian K. Bowden, H. Dubbins, Frank Summers and W. H. Bennett. The auditors were James T. Dewar and Edmunds L. Brown. This Board eventually became the Torres Shire and later the Thursday Island Town Council. At the close of the nineteenth century the chairman was Thomas Fleming, Clerk and assessor David Dietrichson and the members Geo. Hartley, R. Cuherr, W. J. Graham, F. E. Morey, E. E. Slaughter, W. Noelke and C. H. Ashford.

The Torres Strait Service

One factor which played an important part in developing the Torres Strait Service which provided direct communication between North Queensland and Great Britain without transshipment, and the streams of immigrants who reached Queensland by that fleet were landed at their intended destinations without, as was often the case when they came via southern ports, being seduced by the lure of the capital cities against finishing their journey. In keeping with the turbulent history of Thursday Island, this service was launched in a political storm. The service dates back to July 1860, when the then Premier (Sir R. G. W. Herbert) carried a motion through the Legislative Assembly: 1. That in consequence of a late arrangement under which English mail steamers no longer proceed beyond Melbourne. 2. That the route via Torres Straits and Singapore is likely to prove more expeditious and economical and to offer greater general advantages to Queensland than any other. 3. That communications ought to be entered into between the Government of Queensland and the Governments of other colonies (New South Wales and New Zealand) with a view to considering adoption of the above route and the subsidy payable… But Herbert got no further than an expression of opinion and it was twenty years before the masterful Sir Thomas McIlwraith forced the necessary measure through Parliament to provide what ultimately became a great boon.

McIlwraith obtained a tentative contract with the British India Company which had to be ratified by Parliament by 6th August. The contract provided a subsidy of £55,000 per annum for five years, and Sir Samuel Griffith led a very strenuous and determined opposition against this measure which he regarded as unconstitutional.

The date of ratification (6th August) passed without the necessary Parliamentary sanction, and Griffith cabled the company that the Opposition, claiming a large majority, repudiated the contract. Not to be beaten, McIlwraith arranged for the ratification date to be extended from 6th to 12th August, and on the latter date cabled the company: The Legislative Assembly not having disagreed to the mail contract it stands ratified.

At the beginning of the twentieth century there were 260 boats ranging from ten to thirty tons, employing about 1600 men, engaged in the pearl shell and beche-de-mer fisheries. The Resident Police Magistrate was the Hon. John Douglas, with Mr W. G. Moran as Clerk of Petty Sessions. The Government Medical Officer was E. Tilston, the hospital doctor being G. B. White. The average attendance at the State School was seventy, the Head Teacher, Mr P. Robinson, being assisted by one pupil teacher.

It is fitting to bring this paper to a close with a brief reference to the part played by the Hon. John Douglas in the history of Thursday Island. It was he who sponsored the Bill for the annexation of the islands, and the transfer of the settlement from Somerset to Thursday Island. The Hon. John Douglas first visited Thursday Island in 1877 to choose the site of the school and post office reserves. As he said, ‘It certainly never occurred to me then that I should be privileged in my latter years to take an active share in the administration of the affairs of the islands in the Strait’. As Government Resident and Police Magistrate from 1885 he left his mark in Torres Strait.

Notes on Green Hill Fort, Thursday Island

Green Hill Fort on Thursday Island was built between 1891 and 1893 as part of Australia’s defence against a possible Russian invasion. It was eventually decommissioned some-time in 1927 and the buildings were demolished and the guns spiked. Green Hill is a small grassy hill about 58 metres above sea level at the western end of Thursday Island.

The guns that formed part of the pre-Federation fort were:

Four rifle muzzle-loading (RML) 7-inch guns

Four sixteen-pounders (King 1983:98)

Two Mark VI 6-inch breech loading guns

Two Mark IV 6-inch breech loading guns

There are five rooms with 600 mm thick concrete walls used for ammunition storage. The initial buildings on site were the general storeroom, shell store, cordite room, lamp room and artillery store. A timber and corrugated iron guardhouse was also built over a 20,000 gallon underground well. A cooling plant, machine room and a powder room were added in 1912. Air conditioning ducts were installed from the cooling plant machine room to the cordite store.