By Dennis J Weatherall JP TM AFAITT(L) LSM – Volunteer Researcher

HMAS Assault, also known as the Amphibious Training Centre to American personnel, was a combined operations establishment for training Allied personnel in all aspects of amphibious warfare. It also provided operational and logistics support to amphibious units of the Royal Australian Navy. During its short three-year commission (September 1942 to August 1945) more than 22,000 personnel undertook training which was essential for the successful repulsion of Japanese forces from the Pacific Islands. This paper provides insight into its establishment, roles, challenges confronted and personnel who played a significant role in contributing to victory in the Pacific.

In 1942 Australian Forces were heavily committed to the War against Germany and its Allies in Europe then in its third year. As in WWI, RAN units were under the command of the Admiralty and employed against Italy in the Mediterranean and elsewhere. The Japanese had entered the war in Australia’s own area of interest with the invasion of South East Asian countries and the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Following the rapid Japanese conquest by the Japanese of Malaya and the “Fall of Fortress Singapore” on 15th February, Australia found itself threatened for the first time since British settlement. The subsequent Japanese advance through the Dutch East Indies and islands in the South-West Pacific basin brought WWII to the Australian mainland on 19 February 1942 with the bombing of Darwin.

However, by early 1942, the Allies were already planning for the invasion of Europe and had successfully established a “Combined Operations Command”. Australian planners then urged the Australian Government to seek British assistance with information and expertise to establish a similar Australian Directorate. This was essential if Japanese forces were to be repelled from the Pacific Islands. Fortuitously service by many Australians in all three British Services meant there was a pool of experienced Australian available to return home with a small number of British Officers for the task of establishing an indigenous amphibious capability.

The officers seconded to establish an Australian “Combined Operations Base” were; Commander T. W. Cook RAN (ex CO HMS Tormentor British Combined Operations School) , Lieutenant Colonel M. Hope – Royal Artillery, Lieutenant Colonel T. K. Walker – Royal Marines, Wing Commander A.M. Murdoch – RAAF, Lieutenant Commander H. George – RANVR, and Lieutenant D. Richardson – RANVR. All had “Combined Operations” experience and understood the importance of an amphibious capability to push the Japanese out of New Guinea, Borneo, Bougainville and occupied islands between Australia and Japan.

In June 1942, the Defence planners made a strong recommendation for the formation of the Australian “Combined Operations Directorate” to be set up in Melbourne. On 5 June, 1942 the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff, Captain Frank Getting RAN, Commander Cook and Lieutenant Colonel Hope met with General Macarthur’s Brigadier Chamberlain in General Macarthur’s Headquarters, then located in Melbourne. They were informed that any such “Combined Operations” in Australia would come under the command of Macarthur. There was agreement on an immediate start to train three Divisions – one Australian and two American – in amphibious warfare. The RAN was also to produce one third of the total number of crews required and also provide all naval means (craft and crews) for soldiers undergoing training.

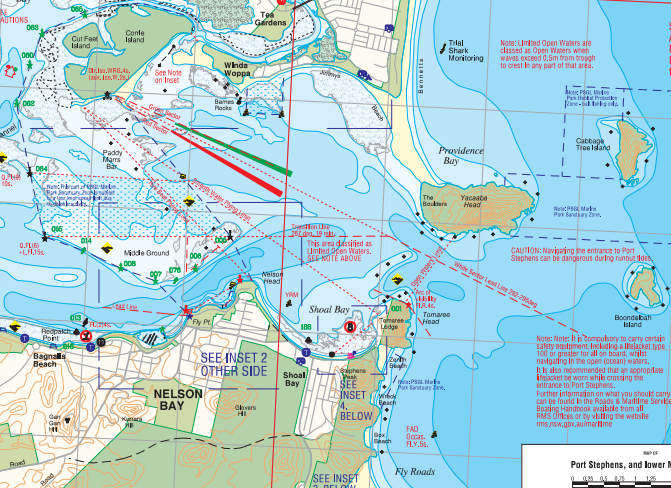

An immediate task for CMDR Cook and LT COL Hope was to find a suitable location to establish the training base. They took to the air and eventually decided that Fly Point in Port Stephens, NSW as an ideal location. A ground inspection confirmed the decision. Then followed the construction from scratch of a shore base in the scrub country away from prying eyes. Training for all facets of amphibious operations (sea, land the air) could be conducted in the immediate vicinity. From a security perspective, Port Stephens being a small fishing village with little other activity in the area, the location was ideal.

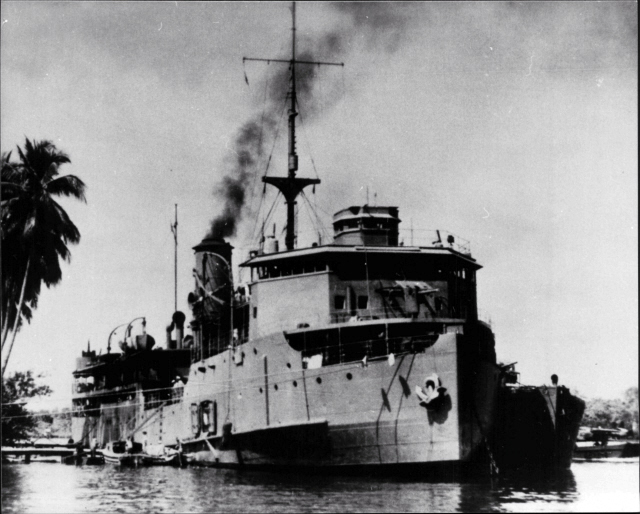

No time was lost awaiting the building of the base. The Auxiliary Merchant Cruiser HMAS Westralia was loaned as an accommodation vessel from 21 August, 1942 and on 1 September, 1942 HMAS Assault was actually commissioned in Westralia with 24 Officers and 280 Seamen Trainees. HMAS Westralia was then designated as a Landing Ship Infantry when she arrived in Port Stephens on 3 September 1942.

It was hoped at the time that Westralia’s sister ships HMA Ships Manora and Kanimbla would also be made available as LSI’s and fitted out with landing craft. Provision was made in planning for these ships to be made available and Flinders Naval Depot made aware of the requirement for trained ratings as they finished their basic training. The Naval Board was supportive and the training pipeline to HMAS Assault commenced.

At the same time, the requirement for landing craft was presented to the Naval Board. It was recommended that these be built locally as they could not be delivered off-the-shelf. Until purpose-built craft were available, training was undertaken in nine motor boats requisitioned from civilian sources. These were referred to by the sailors as the “Hollywood Fleet”. Folding- boats were provided by the Army.

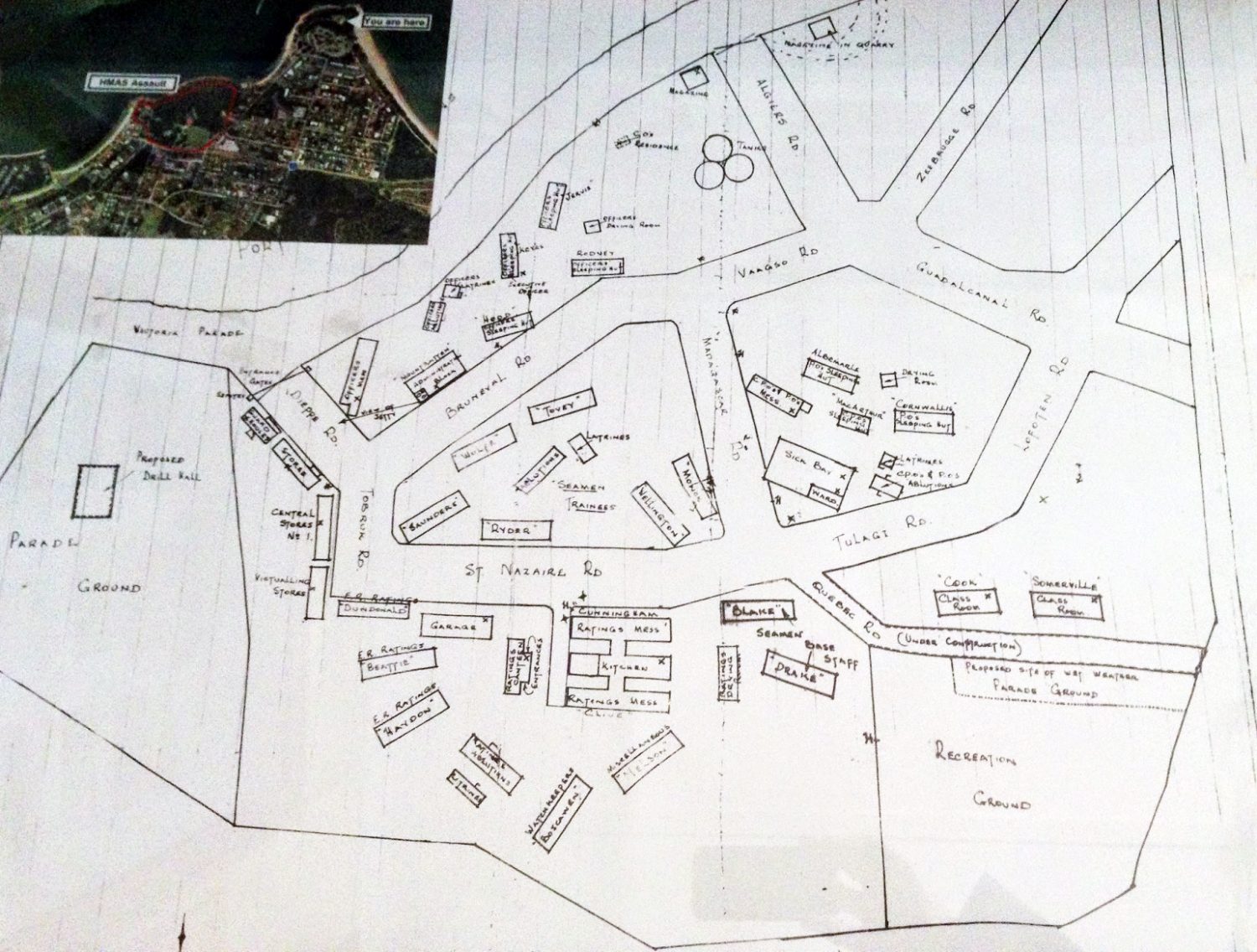

The base was designed from ground up with layout the was first consideration. Accommodation for all personnel, moorings, piers, slipways, maintenance facilities all had to be built in a virgin bushland setting 125 miles north of Sydney.

On 1 October 1943, one year after commissioning ashore it was reported that 100 Officers, 100 Coxswains, 453 Boat Crews, 250 Stokers, 40 Landing Craft Signalmen and 120 Naval Beach Party Commandos had been trained. As it took until 10 December 1942 to complete all buildings the majority many trainees and staff were accommodated in HMAS Westralia for the first three months. Some 90 officers and men were transferred to a Queensland Army Camp at Toorbul following their training. They were then used to train soldiers in certain phases of amphibious warfare. This camp was later taken over by the American Forces and the Australians reposted to Assault.

The roles of HMAS Assault were to train;

- Officers and ratings for boat crews,

- Naval Commandos for beach parties,

- combined operations signal teams, both Naval and Army with spares posted to the LSI vessels,

- act as a base for LSI’s arranging transport, victualling, spares and repairs,

- designated Commanding Naval Officers to also be Naval Officer in Command of a post.

By 1 October 1943 all three LSIs had been supplied with Assault trained Officers and Boat Crews, along with Beach Commandos, with a factor of 25% spare trained personnel.

On 1 October 1943 HMAS Assault commenced a new phase in its evolution. With its training role mature and sufficient personnel trained to commence amphibious landings to re-take Japanese occupied territory the new role was logistics support. This involved;

- operating as a stores depot supplying spare parts for the landing craft carried on the LSI’s,

- operating as a pool depot for a reserve of trained combined operations personnel, and

- assisting with the base’s trained boat crews in training US soldiers passing through the Amphibious Training Centre (ATC).

The ATC was the American organisation responsible for training assault troops and to which HMAS Assault was responsible. Some 22,000 men from various services received amphibious training including 2,000 Australians. The remainder were all US Servicemen.

As expected, trainees who had completed their training at Assault had to wait for postings to the LSI’s and in some cases, subject to their wait time, had to be brought back for various refresher courses. This occurred when such trained personnel had returned to their previous establishments to awaiting a billet on an LSI. As the Assault expanded and more accommodation became available trained personnel were kept onboard Assault and kept in training until posted to sea.

In the early stages of developing HMAS Assault, there was a shortage of actual landing craft until the locally-built Australian craft were delivered. This shortage made training in craft handling difficult. Until December 1942, only two LCA’s (Landing Craft Assault) were actually operational at the base and the requisition civilian craft (nothing like a LCA) were used in conjunction with the two LCA’s. Although not ideal, training continued with what was available. Whilst allowing crews to experience handling twin screw boats, these civilian craft couldn’t replicate running ashore and beaching craft in all conditions of weather and sea states.

On 14 December 1942 sufficient American landing craft arrived for the USN Advanced Landing Craft Base, the name of the American base at Port Stephens. Following delivery of these craft training in all conditions could be undertaken. The Port was an excellent location as within the immediate area and along the coast were steep and shallow, sandy beaches, with or without surf, rock, mud and mangrove areas, all in close proximity to the base.

On 10 January 1943 the Australian-built LCA’s started to arrive. This allowed Assault to return five requisitioned craft to Sydney for deployment to other urgent tasks. On 20 March 1943 19 American landing craft were handed over to Assault control by the American Landing Force Equipment Depot (LFED). Finally there was sufficient craft of various types to provide instruction and gain experience.

In addition to the LSIs, Westralia and Manora, HMAS Assault had on its warrant list several other vessels. These were;

- HMAS Ping Wo, a tender for the transportation of water and stores for the LSIs. She was also used as a training ship. Ping Wo and was an ex Chinese River Steamer of 2,000 tons.

- HMAS Gumleaf, an ex Seine Trawler, 55 ft OA used for escort, patrol and salvage duties.

- HMA Ships Flying Cloud and Kweena, both Auxiliary Patrol Vessels’,

- A variety of landing craft:

- LST – Landing ship tank x 1 (US)

- LCI – Landing craft infantry x 12 (US)

- LCT – Landing craft tank x 4 (US)

- LCM – Landing craft mechanised x 7 (US), 4 loaned to “Assault”

- APC – Auxiliary patrol craft x 2 (US)

- LCV – Landing craft vehicle x 67 (US), 14 loaned to “Assault”

- LCP – Landing craft personnel x 15 (US), 1 loaned to “Assault”

- LCS – Landing craft support x 7 (US)

- LCA – Landing craft assault x 9 (AU)

- Motor boats x 4 (AU), of which 38 were under “Assault’s” control

- Three boat ramps for slipping, scraping and painting

The buildings ashore in HMAS Assault consisted of 67 structures. These were classified as “C” series-type unlined, galvanised iron huts. They were located 800 yards from the landing craft moorings and general pier area. They were described as hot in summer and freezing in winter, but this was nothing new in time of war!

The base was originally designed for 500 officers and men, but as many as 870 were housed, of which 70 were officers and 800 other ranks. As in the British counterpart establishments, roads were named after successful operations and buildings named after military personnel who had achieved success in Combined Operations to date in WWII.

A jetty to suit naval requirements was constructed using as its basis, an existing jetty on requisitioned land. It was altered and extended considerably to reach out 510 feet with a width of 12 feet, and at the end an L-shaped return of 162 feet which formed a boat compound. The outer perimeter of the jetty was enclosed with planking set 3” apart to act as a breakwater. The pier had a depth of 7 feet alongside at low water and could handle 5 ton loads with fuelling points located along its length.

Unfortunately, by late 1943 slipping facilities for the repair and painting of boats were found lacking. This was overcome by the employment of naval divers and by the end of the year the initial work started by civilian contractors was completed. The result was a working slipway and boat shed. Prior to completion, boats had to be slipped at Tea Gardens, some 3 miles distance, and only when the facilities there were available.

The Assault boat shed was 112 feet long x 30 feet wide, set up with a winch to haul boats, along with machinery for general maintenance. The slipway had a capacity of 25 tons but the depth of water limited the size of the vessel that could be slipped. At high water, it was reported only 4 feet 6 inches at the water end, and only 2 feet 6 inches at the shore side. It meant that only boats with an average draft of 3 feet 6 inches could be slipped, and only at high water. The solution would be to extend the slipway another 40 feet at the water end. However, no record could be found of this ever being done.

The slipway came with three cradles which allowed three boats to be lifted out of the water at any one time for maintenance.

Located nearby was the Engineers’ Work Shop, a building of 114 feet in length and width of 42 feet. It was well equipped with; lathes, milling machines, drills, shaping machines, a 60-ton hydraulic press, valve grinder, bench drills, punch shears and an electric welding unit.

One of the biggest problems for the base was spare parts for the overhaul of the landing craft engines, as these were mainly of US origin. Lack of the smallest part could keep a craft alongside for weeks and impact practical craft ship handling exercises.

HMAS Assault was well-located with quite a pleasant temperate climate. However, summer heat could make it more sub-tropical. Unlike bases situated in far Northern Queensland, there was little in the way of environmentally induced illness. The base had a capable hospital which treated mainly casualties from vigorous activities. On 24 May 1943 casualties from a PBY-Consolidated Catalina which crashed into Port Stephens were treated on base. Post WWII the base hospital became the Port Stephens civilian hospital.

Men came and trained, then left. The base had ample sporting facilities available to keep the trainees amused; swimming, surfing, fishing, along with cricket in summer and football in the winter months. In 1943, the Assault rugby team won the First Grade Newcastle League.

Like all bases in war time, religious observances were conducted by Navy Chaplains and the YMCA and Australian Comforts Fund people ran the recreation, with regular parties and entertainment.

The entire concept of establishing HMAS Assault was to train Australian and American sailors and soldiers in the art of amphibious warfare, and to get the Army conditioned to working with the Navy, and vice-versa. When the American Training Group was established the two facilities were combined and designated the ATC – Amphibious Training Centre. This took place in February 1943 under the overall command of the Commander South West Pacific Force, Rear Admiral Daniel E Barbey USN, who answered directly to General Macarthur.

This brought all such training in Australia under American command. From this time until training concluded US Marines, RAN sailors and US Army personnel served together on base.

Training at HMAS Assault was, to say the least, intense. It covered every conceivable aspect of amphibious landing operations to face the enemy on inhospitable landing sites. RAN sailors took part in all the courses, from assaulting beaches to coxswaining landing craft and other vessels of opportunity, not only to meet the enemy face on, but to learn clandestine skills for infiltrating enemy lines. The specially selected naval beach commandos were instructed in all makes and models of weapons and explosives, as well as hand-to-hand unarmed combat.

Lieutenant Donald Davidson RANVR was the chief instructor in hand-to-hand combat. No-one knew from where he originated but at war’s end those he trained knew where he’d been. He was training officer for those selected to be “Special Service Beach Commandos” and sailed on MV Krait, the Japanese fishing boat captured before Singapore surrendered. It was known as the “fishing boat that went to war”! LEUT Davidson was 2IC to Major Ivan Lyons in Krait. Before this Davidson had established the “Special Reconnaissance Department” based on Fraser Island, Queensland. He was later a member of the ill-fated ‘Rimau’ raid on Japanese shipping in Singapore. LEUT Davison was severely wounded in this operation and holed up on Tapai Island. So he wasn’t taken prisoner and tortured for what he knew he took his ‘last resort’ cyanide tablet carried by operatives. Major Lyons died in a fire fight on Soren Island, it’s said whilst holding off over one hundred Japanese soldiers.

Many HMAS Assault trainees went to various postings in the three LSIs. There they operated their landing craft in operations to expel Japanese forces from conquered territory. Some were employed in the Special Operations with Lyons and Davidson, others were posted to US Military Small Ships and even wore US Army uniform. They served on these small vessels throughout the South West Pacific theatre as far as Japan until the end of hostilities.

In early March 1944, training at Assault ceased. It had served its purpose well. On 4 August 1944 the base was designated to “care and maintenance” and manning was reduced to just one officer and twenty-four other rates.

After the dropping of the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Monday 6 August 1945 and three days later the second A-Bomb on Nagasaki the Japanese surrendered and so ended WWII when General Macarthur signed the surrender in Tokyo Bay onboard USS Missouri on Sunday 2 September 1945.

On 7 August 1945 HMAS Assault was decommissioned but not abandoned – it was transferred to the Royal Navy and used as the shore depot for the British Pacific Fleet, known also as the “Phantom Fleet”.

References:

- RAN website HMAS Assault – history

- Sailor & Commando – A.E. Ted Jones, 1942-46, Hesperian Press ISBN 0 85905253 2

- Commanding Officers’ Monthly Reports to the Secretary, Naval Office Melbourne

- Australian War Memorial Canberra – website

- Photographs from various sites – public accessible

- National Archives – Canberra

- Huddart Parker Shipping Company History