- Author

- Lind, L.J.

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1974 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Banjo Paterson, the Australian poet, once deserted his dusty sunlit plains to write a poem of the navy. The subject he chose was the saga of HMS Calliope at Apia in 1889. Paterson succeeded in capturing the era of wooden ships and iron men as few poets have done before or after him.

‘By the far Samoan shore,

Where the league long rollers pour

All the wash of the Pacific on the coralguarded bay,

Riding proudly at their ease,

In the calm of tropic seas

The three great nations’ warships at their anchors proudly lay.’

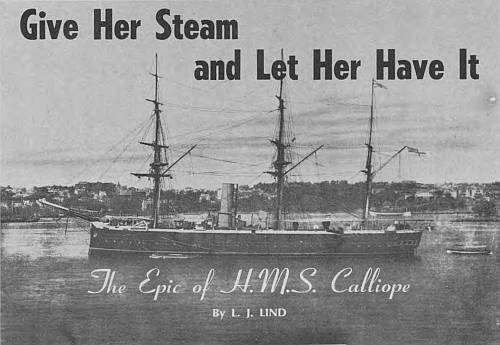

Early in March 1889, the light cruiser HMS Calliope slipped away from her berth at the Naval Depot, Garden Island, and turned her ornamental bows towards Samoa. The skipper, Captain Kane, carried instructions to show the flag in Apia Harbour and forestall any annexation attempts by USA and German fleets known to be in the area.

The voyage was uneventful and no foreign warships were sighted until Calliope steamed through the narrow coral entrance to Apia Harbour. There were the USA and German fleets impudently riding at anchor. The lookout on Calliope called their names. Trenton, Vandalia and Nipsic of the US Navy and Adler, Eber and Olga of the German Navy.

Britannia ruled the waves and Captain Kane was not impressed by ‘wet behind the ears’ Yankees or stiff-necked Prussians. Streaming a black cloud of Westport coal smoke, Calliope steamed through the opposing fleets and dropped her anchor close to the beach.

‘When the gentle offshore breeze,

That had scarcely stirred the trees,

Dropped down to utter stillness, and the glass began to fall,

Away across the main

Lowered the coming hurricane,

And far away to seaward hung the cloud wrack like a pall.’

The barometer began to fall on Thursday 14th March. Skippers of the warships in Apia Harbour ordered steam to be raised. However, the shore authorities were unconcerned. ‘Just a few heavy showers – the normal weather pattern.’

Friday morning saw the barometer still lower. The sailors’ eyes were on the threatening skies, now a leaden black. Again the shore authorities chided them for worrying.

In the dark hours of Saturday morning a hurricane struck Samoa. The wind screeched across the low coral reefs and gusts of 80 miles per hour were registered aboard the ships. Enormous waves crashed down on the coral and blotted out the narrow escape channel. The twenty ships in Apia Harbour were caught in a boiling cauldron.

‘When the grey dawn broke at last

And the long, long night was past,

While the hurricane redoubled lest its prey should steal away,

On the rocks, all smashed and strown,

Were the German vessels thrown,

While the Yankees, swamped and helpless, drifted shorewards down the bay.

Then at last spoke Captain Kane,

‘All our anchors are in vain,

Give her steam and let her have it, lads, we’ll fight her out to sea’

Dawn didn’t break on the 16th. No light pierced the blackened skies, and sea and sky were joined by a fall of flying spume. Every ship in the harbour was in trouble. Buffeted by the punching fury of the 80 mile per hour hurricane, anchors dragged and slowly the ships closed with the maws of the waiting coral.

First to go was the German Eber. Lifted bodily by a monstrous wave, she was dashed in two on the reef. Five out of her crew of 80 were to survive.

Two hours later the second German ship, Adler, was picked up and tossed like a cork on to the coral. Her smashed hulk came to rest 100 yards inland. Thirty German sailors died in those brief minutes.

The American Nipsic did not wait her turn. Losing her cables, she turned and ran for the beach. Midway across the harbour she collided with the remaining German ship, Olga. Ordering her last reserve of steam, the skipper of Nipsic wrenched his ship clear of the Olga and ploughed high and dry on the sand between two reefs. By some miracle unexplained Nipsic suffered no casualties.

Midmorning found four warships still afloat. Most of the merchant ships were wrecked and the hurricane continued unabated.

The USS Vandalia followed the Nipsic. She turned and ran for the beach, but the sea gods weren’t to be cheated. A wave caught her beam on and smashed her on the reef. Forty three of her crew died and the survivors were to cling many hours on the rigging before rescue.

Three ships remained – Calliope, Trenton and the disabled Olga.

Late in the afternoon Trenton began to bear down on the Calliope which was closest to the reef. Captain Kane, far from beaten, was biding his time. All through the long day he had fed Calliope’s fires with the fine Westport coal. Steam was up and Kane waited.

The distance between Trenton and Calliope narrowed. The reef was only feet away. Captain Kane roared his red meat order down the engine voice pipe and Calliope pranced forward like a thoroughbred.

‘Like a foam flake tossed and thrown,

She could barely hold her own,

While the other ships all helplessly were drifting to the lee,

Through the smother and the rout,

The Calliope steamed out

And they cheered her from the Trenton that was foundering in the sea.’

The Britisher was the only ship in the harbour to challenge the sea. Kane was gambling on finding the treacherous channel in the reef and driving his ship through the foaming funnel before the cross-seas cast him up. Britannia ruled the waves and Calliope would teach those foreigners a lesson in skill and courage.

Plunging past the doomed Trenton, Kane drove his ship directly at the reef. From the Trenton came the Yankee cheers and then all was lost in a world of foam and spume.

Calliope found the opening in the reef and like a live creature squirmed her way through the crashing mountains of water. Clawing firstly deep water and then thin air, her propellers thrust her forward to freedom. One final surge and she was in the open sea, she had cleared the coral entrance by a bare sixty yards. The giant seas that broke on her now were nothing. Proudly she tossed them off and stood out to sea and safety.

Trenton, her fires washed out, awaited her doom. By a miracle a rag of sail was raised and she swung clear of the nearest reef. The skipper steered for the narrow beach and the crew prayed One wave, bigger than its predecessors, lifted Trenton and her bottom grated on the sand.

The helpless Olga, last of the fleet of twenty vessels, was waiting her destiny. Buffeted and broken, her crew clinging desperately to the remaining rigging, she grounded on a stretch of sand at the tip of the reef.

Apia’s black day came to a close. Nineteen good ships lay wrecked and the sea had claimed over 100 victims. The town of Apia and most of Samoa was devastated.

Out to sea the sole survivor Calliope, named after the Greek Goddess of heroic poetry, wallowed in the heaving waves. A wooden ship manned by iron men and fired with good Westport coal, the finest in the world, as the New Zealanders claimed.

When the weather moderated Calliope returned to Apia and brought relief to the stricken town. Emergency stores and medical supplies were landed and essential services restored.

On 4th April Calliope arrived at Sydney for a tumultuous welcome. When the ship berthed at Garden Island the harbour foreshores were lined with cheering crowds. It was a heroic welcome for the goddess of heroic poetry.

The fame of Calliope lived on for many years, particularly in New Zealand. Generations of New Zealand schoolchildren read in their school magazines of Calliope’s battle with the sea gods and how ‘the fine Westport coal, the best in the world,’ tipped the scales in her favour. (The Australian Auxiliary Squadron was bunkered in New Zealand in the late 19th century.)