- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Adelaide II

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Phillip Hart with contribution from Greg Mapson

This article is a personal recollection of the grounding of HMAS Adelaide that occurred nearly forty years ago. SBLT Phillip Hart was the Assistant Officer of the Watch (AOOW) on the bridge at the time of the grounding and LEUT Greg Mapson was the Officer of the Watch of the preceding watch and the Diving Officer who inspected the ship for damage. The information has been cross-checked with the transcript of the Court Martial of CMDR Glenn Lamperd.

HMAS Adelaide (II) FFG01 was commissioned into the RAN on 15 November 1980 at Todd Seattle Shipyards. The ensuing months leading up to the grounding were spent preparing the crew and ship for sea under the command of CMDR Glenn Lamperd. These activities included a comprehensive training schedule of both harbour and at sea training activities overseen by the US Navy DESRON 9 FFG Training Team (all US built RAN FFGs were attached to DESRON 9). The ship had passed all harbour and sea training phases without incident and according to the Head of the training team, CAPT Champlain USN, Adelaide’s ships company had passed all tests with the highest marks recorded in the training program to date (note: Adelaide was hull No 17 and some 15 ships of this series had already been commissioned).

On 7 January 1981 the ship departed Seattle for Carr Inlet some 25 nms south (deep within the Puget Sound Island area). The Carr Inlet Acoustic Range (CAIR) was a deep-water sound ranging facility primarily set up to conduct ranging of USN SSBNs, such was the depth of water. Having sent families south to Long Beach, California and surrounds the previous month, Adelaide was not scheduled to return to Seattle after sound ranging, so the departure from Seattle that day was also farewell to the city of its birth. A sizeable crowd of wellwishers waved the ship goodbye that cold morning in January. The wind was blowing from the south east straight off the snow peaked Mount Rainier and in very cold conditions, the ship’s company went about their tasks with little knowledge of what was to follow early the following morning. As an aside, the ship had embarked a significant media contingent to film the departure and to spend the day on board during the transit to Carr Inlet.

Arrival at Carr Inlet at around 1300 that day occurred without incident. The first activity was to embark the NAVSEA Ranging team from the CAIR facility and to set up instrumentation onboard. The sound trial required a number of sensors to be positioned in a variety of places within the ship (primarily in machinery spaces) to record the internal noise environment of the ship. The intention was to conduct sound range runs with differing machinery states at differing speeds. The FFG class was fitted with Prairie Masker and Agouti (noise-reduction systems) so a number of runs were scheduled to test this system. Part of the setup included fitting a mini ranger navigation system on the bridge. At the time this ranging system was a relatively new precise fixing system and whilst very efficient in providing sub metric accuracy, the display was very rudimentary and in the case that day, was a very basic screen with distance down range and cross track without any imagery or reference to any nearby land (very different to digital maps based systems in use today).

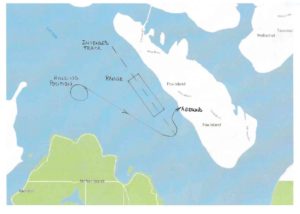

Carr Inlet is a relatively narrow waterway running SE/NW between Fox Island to the North and McNeil Island to the south, with a width of 1.8 – 2.0 nm in the vicinity of the sound range. The first sound range runs got underway sometime mid-afternoon on 7 January 1981. These proceeded without incident. Most of the initial runs during that afternoon watch were conducted at low speed. The higher speed runs were scheduled for the First and Middle watches as the height of tide would then be lowest (so scheduled to reduce wash upon Fox Island).

Adelaide was the first ship in the RAN to attempt minimum manning. The FFG class when commissioned had a ship’s company strength of 185 personnel. This would grow to 210 with aircrew embarked. Relevant to the grounding was the number of qualified Officers of the Watch (OOW). There were three billeted, consisting of the Navigator, LEUT Steve Howlett, LEUT David Garnock and LEUT Greg Mapson. The Navigating Officer (NAVO), had the departure as was the norm along with Special Sea Dutymen OOW, LEUT Garnock who continued as the OOW for the remainder of the forenoon watch (once SSD had fallen out). The NAVO remained around the bridge throughout the remainder of the forenoon, prior to taking lunch in order to return to the bridge to relieve LEUT Garnock for the afternoon watch. LEUT Mapson was also the Public Relations Officer and had escort duties with the embarked media teams, so LEUT Garnock took the Dogs and LEUT Mapson, the First after the media teams had disembarked by boat at Carr Inlet. LCDR Mike Harrison, who was the Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer (ASWO, also known as TAS), was given the Middle Watch to provide the NAVO some rest as the ship was planned to be in pilotage waters for most of the day, although the ship did not remain closed up at SSD (this was to be a major issue at the subsequent Courts Martial). Up until the sound ranging, very few of the Principal Warfare Officers (PWOs) had spent much time on the bridge as Watchkeepers and prior to LCDR Harrison taking over the watch that night, had only kept one or two watches as OOW, during sea trials and workup.

The Grounding

As the day progressed, the sound ranging runs increased in speed such that during the First Watch, the initial runs at higher speeds were conducted. Full speed for Adelaide was in the vicinity of 29/30 knots. Two runs at 25 knots were conducted during the evening leading up to the grounding. Due to the relatively narrow inlet, the procedure for each run was to pass within 10 metres of the hydrophones which were some 80 metres below on the seabed, proceed down range 2000 metres and conduct a Williamson Turn to come back down the track for the next run. All runs up until the change of watch for the Middle Watch had been conducted without incident. The Captain returned to the bridge at approximately 2130 after taking dinner in his cabin. At 2340 approximately, after completion of a 25 knot run, the ship was hove to just northwest of range centre but facing south east so as to conduct a boat transfer to change over NAVSEA staff who were coming from the range hut on the shore of Fox Island, 1 nm on the port beam.

The changeover did not run smoothly as the ships company had difficulty setting up upper deck lighting to facilitate the transfer at the boarding station midships on the port side, adjacent to the Mk 46 torpedo tubes. This was the first time they had set up this lighting. The delay caused a follow-on delay to the handover on the bridge. The oncoming OOW, LCDR Mike Harrison, was under some pressure as he was also acting as the Signals Communication Officer (SCO) due to LEUT ‘Sam’ Hughes having been landed for medical attention a couple of weeks previously. After the boat transfer was completed, the handover by LEUT Mapson to LCDR Harrison was completed at approximately 0025. The assistant OOW was SBLT Phillip Hart who had joined the ship the previous day. His role that evening was to fix the ship as the OOW would be fully committed conning the ship.

The first run of the middle watch commenced from the south-eastern end of the range heading north-west. The NAVSEA staff had trouble getting the mini ranger operating after the crew changeout and so the run was aborted. The ship headed to an area of safe, open water to the west of the top of the range and the speed was set to zero. The time was about 0030.

The range issue was not quickly resolved. SBLT Hart took regular fixes of the position of the ship on the chart and updated the Notebook and Log. In plotting the fixes, Hart noticed that the ship was not stationary in the water. The movement could not be explained by tidal stream alone. In fact, the ship moved sternward and turned to starboard, completing circles greater than the ship’s length. New technology to the RAN at the time, FFGs had a single, controllable-pitch propeller (CPP) and the ship would increase speed initially by increasing the pitch of the propeller blades. When an FFG’s speed was set to zero, the propeller still rotated at approximately 35 rpm and because the blades actually had a slight negative pitch, they would create a sternward movement through the water. Also, as the rudder is slightly offset from the centreline of the ship and due to paddlewheel effect, the ship’s stern moved to starboard.

At about 0220, the range staff had fixed the issue and the ship was ready to continue. The weather was fine and the visibility was good, albeit a very dark night. The Captain and OOW were on the bridge. The NAVO was in the Charthouse at the back of the bridge. There was a discussion between the range staff and our senior officers that due to restrictions caused by tidal levels in the inlet, we only had a limited time to do a high-speed run. It was decided to make this next run at 25 knots.

The OOW asked for a course to the south-eastern end of the inlet. He ordered speed for 15 knots and helm to come around to the heading of 115°. The sound of the gas turbines rose significantly and the bow lifted with the quick acceleration. As the ship had started some 200 yards starboard of track adjacent to range centre, the 115° course would take the ship to an intersection with the 135°/315° track some 2000 yards down range whereupon it was the OOW’s intention to do a 160° turn to port and regain the 315° leg for the run as guided by the mini ranger operator (a NAVSEA technician who was calling ranges downrange and cross track error at the back of the bridge). Upon reaching a point 2000 yards down range and now at 25 knots, the OOW gave orders for the helm to put over to port to commence the turn. As the ship turned to port approaching north, the Captain, who now was sitting in his chair, remarked to LCDR Harrison, ‘Aren’t you supposed to do a Williamson turn? Do a Williamson turn!’. The OOW who had not really gained full situational awareness of the sea room to port, paused as the ship continued to turn to port and then acquiesced and without understanding that he was already now some distance displaced to port of the range centerline, ordered the helm be put back to starboard.

Lurking no more than 500 yards to starboard was the very steep-to-shore Fox Island. As the night was very dark, it was hard for anyone to discern the dark evergreen forested shoreline against the dark sky. The first person to understand the peril the ship was now in as it commenced its turn to starboard directly towards the shore was the Captain. He had discerned the looming forest in the darkness. As bridge staff later recalled, he let out an expletive along the lines of ‘Look out TAS, you’re going to hit that island’ and jumping from his chair, he reached over the console and pulled the T Bar Prop/Speed control back to full astern. The FFG CPP takes close to 25 seconds to pivot its blades from full ahead to full astern. Alas too late, as the ship was continuing to turn to starboard at speed and at almost perpendicular to the fast-approaching shoreline, she grounded. It was 0236 on 8 January 1981.

Hart reports: ‘My first indication that something was amiss was when I was being lifted off my feet and thrown forward. The ship was decelerating very quickly and the bow was lifting. I used both hands to grip the sides of the chart table to stop falling toward the bow. Within seconds, the ship came to a halt. Although going nowhere, the ship was rocking forward and back and the engine had a regular groan as though the ship was trying to move but could not.’ On the bridge, the awareness of having gone aground was very real with the sudden deceleration causing bridge staff to be in no doubt what had happened. Personnel asleep below reported being thrown against bulkheads.

The EM log (a 1.5 metre alloy spear for measuring speed that protruded from the bottom of the hull) sheared off with the last reading on the digital bridge display at the time of 24 knots. Contrary to this information, however, LCDR Ken Tuckey a qualified PWO(N)+ reconstructed the track of Adelaide and provided expert evidence at the subsequent Courts Martial. He determined that with the engine control at full astern, the ship hit the island at about 8 knots.

The shore was primarily sand and shell and came up steeply from 60-80 metres in a very short distance. When the ship came to rest, the bow was amongst the trees of the shoreline and the stern was in approximately 10-12 metres of water. Ordinarily this would have saved any damage to the propeller, however when the CPP commenced to cycle to the astern position, the stern dug down due to the high speed and shallow water effect and the propeller struck the rising ground.

As soon as the ship came to rest, the crew swung into action to assess the damage. The NAVO was sleeping in the charthouse at the back of the bridge and along with other senior officers and staff was summoned to the bridge. The Diving Officer (DIVO), LEUT Mapson, who had been on watch for the First was summoned to get the dive team ready. The USN NAVSEA sound range team were quickly on scene with their boats from shore.

Of interest was a large beach party that was underway a little way along the beach and a small crowd of inebriated souls had gathered on the beach to observe what must have been an unforgettable sight of a large warship spearing up their beach into the bushes. They could hardly believe their eyes and perhaps considered whether their imbibing of things both legal and illegal had gone too far.

The dive team entered the water at approximately 0300 and upon inspection of the propeller it was discovered that four blades had been torn from the hub. The only remaining blade at 3 o’clock was bent like a potato chip. The DIVO remarked at the time that diving into Puget Sound at 0300 in the middle of winter was not what he had in mind for his birthday on that 8th of January. The dive team had not been outfitted with dry suits or any suitable equipment for such cold conditions nor were the ancient and venerable Rugby Upson DC torches suitable for peering through the oil strewn gloom of the damaged propeller area aft. Some weeks later, they returned to the site to locate the blades and EM log and marked them for recovery.

After Damage Control assessments were completed it was then determined to try and back the ship off the shore. As the tide was now rising, the ship was able to be towed backwards by the NAVSEA boats and with the aid of the one serviceable Auxiliary Propulsion Unit (APU), proceeded into deeper water to anchor.

During the early hours of the morning, USN authorities had been notified and tugs were dispatched from Seattle. At first light the media helicopters also appeared, and the grounding was the leading story on Seattle prime time news that evening. Adelaide was under tow by 1000 that morning and arrived back in Seattle later that day to be slid straight into the Lockheed Floating Dry Dock. The next day Seattle Times had the headline ‘Adelaide, Stuck in the Mud’. Having bade our farewells to friends and sweethearts one day, the ship’s company were all suddenly back in town the very next day. Over the ensuing days the most sought-after drink in the local bars around our city birthplace was ‘Adelaide on the Rocks’. Those Rainy City folk had a sense of humour at least.

Eighteen days later, after main shaft alignment, new CPP, APU and a repaint, Adelaide undocked and conducted sea trials. Just a few days later the ship departed Seattle once more to complete sound trials in Carr Inlet. Trials were conducted successfully and the ship finally departed Puget Sound and passaged to San Francisco for a port visit and then onto Long Beach where families were waiting. The next 10 months were taken up with a PSA period to have the sonar and dome fitted and other systems completed. The ship successfully completed Combat System qualifications trials and SM1 Firings at the Pacific Missile Test Centre range, Port Hueneme. The remaining part of trials and qualification activities were completed over the ensuing months without incident and in November, the ship finally departed CONUS for Australia, arriving in early December to commence some 30 years of service to the RAN Fleet. HMAS Adelaide (II) was scuttled on 13 April 2011 near Terrigal on the Central Coast of NSW. Hart states ‘I was standing on the headland at North Avoca, about the closest point one could get to the ship, for her sinking. For better or worse, I was there for the two occasions when HMAS Adelaide touched bottom.’

Notes

The Courts Martial were convened in Long Beach and subsequently the Captain and OOW were found guilty of negligence and dismissed the ship. The Navigating Officer was given Notice to Show Cause why he should not be removed from the ship/sanctioned. He was replaced some two months later.

CMDR Jim Longden RAN was sent out from Australia to replace CMDR Lamperd as was LEUT Robert Cason to replace LCDR Harrison and LCDR Henry Old took over as Navigator. LEUT ‘Sam’ Hughes did not return to the ship due to illness and was replaced by LCDR Tony Lanigan. Adelaide arrived in Sydney on 14 December 1981.