The following paper was delivered by Captain Ralph T Derbidge MBE RAN (Retired) at a reunion (mostly of commissioning crew members and those who deployed to the Vietnam War in the ship in 1969 and 1971). His address was made on 9 May 2018 at Maroochydore, Queensland. It describes a mix of personal experience and memorable anecdotes about his time in the ship.

NUSHIP Brisbane is presently undergoing post-construction trials and is scheduled to be commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy on 27 October 2018. She will be the third ship to bear the name BRISBANE in the history of the RAN.

Her namesake, HMAS Brisbane II (DDG-41), pictured below was commissioned in Boston, USA on 16 December 1967, de-commissioned in Sydney on 19 October 2001 and sunk as a dive site to seaward of Maroochydore on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast on 31 July 2005. Her Battle Honours were Vietnam 1969 and 1971 and Kuwait 1991. One of her 5-inch/54 gun mounts and her bridge are preserved at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra as an interactive display, part of the Conflicts 1945 to Today exhibition. Her mast forms the centrepiece of an impressive memorial at Alexander Headland overlooking the dive site.

You could always tell a DDG commissioning crew-cum-Vietnam War sailor – but you couldn’t tell him much. They were good, and they knew it. There aren’t that many of the breed around anymore – witness tonight. And that goes for the ships they served in. All said and done, they were destroyers and neither we nor anybody else are building steam driven destroyers the way they used to.

Do not be deluded – the RAN’s new DDGs, including NUSHIP Brisbane, can be viewed almost as cruisers, bigger than the light cruisers of WW 2 and, of course, able to deliver much more of a bang for the buck.

And what really defines a destroyer? Let me remind you. It was not always fair winds and a following sea. Nothing short of an iron stomach was sufficient for withstanding a destroyer’s motion. Destroyers could list 45 degrees off keel. The motion of a destroyer at sea is not just up and down but more like a corkscrew churning through water. Our Brisbane could do that, usually at meal hours!

I have been called upon to deliver formal speeches concerning our beloved DDG-41 on a number of occasions – at the sinking of the ship as a dive-wreck to seaward nearby, at the dedication of the splendid mast memorial also near at hand and more recently at the moving plaque dedication ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Our ship features also in a lecture I have given frequently on the RAN in the Vietnam War. Some may view this as a bit odd for I did not command the ship. I was simply the Gunnery Officer through 1970 and 1971.

I really wasn’t intended to serve in that role at all. Previously, I had been the Gunnery Officer of four ships, Anzac, Quiberon, HMS Llandaff while on exchange with the RN, and Vampire – all with British systems and 4-inch or 4.5-inch ammunition and none missile armed, but I knew my stuff. I was serving in Vampire on the screen in the South China Sea in 1969 when Melbourne collided with the USS Evans. Brisbane at this time was on her first Vietnam deployment. One outcome of the collision was an eventual shuffling around of RAN ship commanding officers. Vampire’s CO was shifted to Stalwart, the Executive Officer took over command and I found myself as both Gunnery Officer and the First Lieutenant of D-11 that was soon to undergo a major half-life modernisation.

Then came the unexpected – a pierhead jump to Brisbane in early 1970 because of the resignation around the same period of six RAN gunnery officers, the names of which some of you may recall – Atkins*, Bartlett, Brett-Young, Marrable, Mellish and Playford. This left Officers’ Postings with few options.

I wasn’t too impressed, having been at sea for most of the 1960s, recently married while serving in Vampire and looking forward to some long-overdue shore time. Moreover, I had had no DDG training or experience but was told I could handle it and to get on with it. And so, while Brisbane and Vampire were in maintenance periods, it was into the Tartar missile system books and hardware with David Kitchen and Peter Flynn* and out to HMAS Watson for advice from John McDermott on the Mk 68 gunnery system and 5-inch ammunition.

I managed to get in some brief sea-riding in Perth out of Sydney. On leaving harbour, I sensed things were going to be different when I heard the pipe, “Able Seaman Bloggs report to the wild cat flat!” I turned, puzzled, to the newly joined Chief Boatswains Mate, the legendary Warrant Officer QMG ‘Butch’ Berry*, who explained, “That’s the cable locker. I’m trying to weed out all of this American stuff but I don’t think I will have much joy with turrets instead of gun mounts!”

Enough of this pre-amble – rather than continue in a ‘boots-and-braces’ mode, I have chosen to recall for you some memorable anecdotes about my time in the ship. And, dear ladies, be forewarned – the still handsome hunk of a man here tonight on your arm may not have been the saint you always thought him to be. I will conceal the names of the guilty where relevant in order to protect the innocent. Sadly, in both cases, and others identified in this narrative, many have crossed the bar.

I moved my goods and chattels from Vampire into Brisbane, joining mid-week in Garden Island Dockyard in that summer of 1970 and taking up residence in Cabin 4 forward with Ian MacDougall, the Operations Officer. I was told there was not much sleep left in the bunk vacated by John McDermott. The CO then was the admirable Captain John D Stevens*[i], he having recently relieved Captain Alan A Willis*.

I was the overnight Duty Executive Officer on the Friday night of that first week onboard and aware I was to attend with my wife with other guests a dinner party on the following night in the Wardroom, to be hosted by Captain Stevens and his wife.

On the Saturday morning, well before ‘Call the Hands’, I was abruptly shaken by a very agitated Duty Petty Officer who blurted out, “They’ve broken into the Beer Store!”.

Still half-asleep, I asked “Who, what, where, when?” not having any idea where the Beer Store was at the time.

“The Stokers!” he replied.

I dressed quickly and followed the PO down to the after Stokers’ Mess where I found duty watch bodies and others in all states of undress, asleep in all manner of positions and places and many snoring loudly. Empty beer cans and plates were strewn everywhere. On further inspection, it was discovered that, during the night, the bolts of the hinges to the adjacent heavy steel door giving access to the redundant Tartar missile maintenance barbette (used as the Beer Store) had been knocked out and the door swung open on its large padlock. Nirvana lay ahead for the burglars.

But wait, there’s more to come, and it got worse. The beer was warm.

“There’s ice in the ice-cream room,” said one of the ring-leaders. The ice cream room lock was duly forced and, once inside, the perpetrators couldn’t believe their luck. There, laid out on a bench, was more than a dozen plates with a delectable sweet dish on each. What a treat, and something to be washed down with the soon to be chilled beer.

The subsequent revelry apparently went on long into the silent hours until most fell into a paralytic slumber. The revellers did not know it at the time, but the consumed sweet dishes had been carefully prepared by the chefs on the Friday and placed in the locked ice cream room overnight, to be served up as desserts at the impending Captain’s dinner party.

The revellers also did not know that they were in the process of ruining my whole day for the resultant investigation, with Naval Dockyard Police assistance, went on well into the Saturday afternoon. Moreover, I had to arrange for a local catering firm to provide replacement desserts for the dinner party. At the subsequent assizes, when the Captain was very lenient overall, the guilty showed little contrition for purloining the beer but were most remorseful over misappropriating the Captain’s desserts.

For a while there onboard, the Stokers were not top of my hit parade but a few G & Ts from the then MEOs, the irrepressible Warwick Robinson* and the laconic Ian Watson, placated me and all was soon forgiven.

And so the ship sailed for a shakedown in the East Australia Exercise Area (EAXA) at the end of the maintenance period, with many new personnel embarked following the return from the 1969 Vietnam deployment. A busy year lay ahead in Australian waters. At the end of 1970, Captain Stevens was relieved by Captain R Geoffrey Loosli* during a maintenance period. At the same time, there was another sizeable change of personnel. By this time, the ship’s company knew that Brisbane would be returning to Vietnam and the Gunline from March to October of 1971.

Work-up for the deployment began early in the new year. During the first run of the first AA practice firing under Captain Loosli’s command, the aircraft towed sleeve target was quickly destroyed in spectacular fashion early in the first run by one of the automatically fired salvo of shells. On the horizon, shortly after, could be seen a number of exploding shells followed by the sound of muffled explosions. The Captain, quite pleased by the target destruction, nonetheless queried the source of the horizon explosions. I replied that there must be another ship in the exercise area perhaps firing HE shells at a surface target.

The Captain seemingly bought this at the time. The aircraft, minus target, was released to return to base and the serial terminated. There was little left to do but return to the magazines unexpended shells from the gun mounts. I looked down from the Gun Direction Platform to observe shells being unloaded from Mount 51 and stacked on the forecastle shot mats. They bore the wrong colour coding for the firing. Horror of horrors – it was HEVT ammunition and not VT Prac shells. Despite the Firing Orders for the practice and my preliminary policy broadcast, the magazine crew had fed the wrong ammo to Mount 51. I looked the other way, said nothing to the Captain as the shells were carried below, and months later wrote off the ammo in a Gunline mission off Vietnam. This mistake was never repeated, and a good thing too, for the crew of target towing aircraft are not at all keen on the idea!

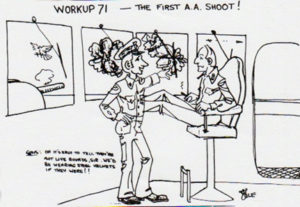

The Captain might have guessed for there is a cartoon titled Workup 71 – First AA Shoot that appears on page 35 of the HMAS BRISBANE 25th Anniversary commemorative book published in 1992.

The cartoon unmistakably depicts me reporting to the equally recognisable Captain Loosli sitting in his chair on the bridge after the shoot. The included caption has me stating, “Oh it’s easy to tell they’re not live rounds, Sir. We’d be wearing steel helmets if they were!”

The workup proceeded smoothly and the last box to be ticked was a successful Overall Readiness Evaluation. The Navigation Officer, Colin Bartlett, and I felt sure we would get a counter battery call for fire while bombarding Beecroft at night during the Final Battle Problem. So, beforehand, and by devious means, we had obtained the grid co-ordinates of just about every likely target (old tram cars and vehicles etc) on the peninsular range. These were printed, given alphabetical designators and a copy provided to Gun Plot for pre-loading into the surface gunnery system.

Sure enough, such a call came through from ashore at which point I requested the Captain to put the wheel hard over, increase to full speed and head due east to seaward while I simultaneously initiated counter battery fire. As the ship heeled over and gathered speed, I got the nod from the NO and CO, barked into the mike to Gun Plot, “Counter battery – Target Delta – Mount 52, six rounds HEPD, fire for effect – engage”. This all happened quite quickly, which was the whole point of the exercise.

With the rounds in the air, a startled Fleet Training Group observer burst into the Operations Room and screamed, “Who said anything about firing live rounds?” Moments later, over the shore bombardment net, the spotter reported loud and clear, “Good shooting. Target destroyed. Bravo Zulu!” Nothing further was said by the FTG observer, at least not to me!

And so, the ship subsequently sailed north from Sydney, acquitted herself well on the seven months Vietnam deployment while firing some 7,000 rounds on the Gunline and returned home in October to be the last RAN ship to be so deployed in that war. Early in the new year, the ship was awarded the Gloucester Cup for 1971 and I finally had my shore time at the Australian Embassy in Washington DC, USA. And the rest, they say, is history.

Maybe, but not quite. For not forgotten by some was Cebu City in the southern Philippines where the ship made a two day port call towards the end of the deployment prior to a final period on the Gunline. The legacy of that so-called goodwill visit could have been disastrous for the ship and her reputation. Common sense prevailed and the bad news was kept in-house and out of the official record.

The impending drama began on the first day with the ship berthed portside to at a large godown with no perimeter fence and little local external security. That afternoon, prior to an official reception onboard, the city Police Chief visited and asked to see the Gunnery Officer. I offered him tea and sandwiches in the Wardroom during the course of which he asked me if I would like to go flying with him in his private aircraft the next day. Then came the catch – in return I might provide him with some small arms ammunition, both pistol and rifle. He explained that the paranoid President Marcos, fearing a coup, had emasculated the nation’s police force by denying them ammunition for their weapons. As diplomatically adept as could be, I thanked him for his flying invitation, told him I was required onboard for duty the next day and declined firmly his bid for ammunition. He persisted but eventually accepted my stand and I farewelled him at the gangway.

During both nights in port, better notice might have been taken by more senior duty personnel of small waterborne craft in the vicinity of the ship and sailors casually, and apparently innocently, fishing over the outboard starboard side with rods and handlines.

Senior management was no doubt relieved to be free of Cebu City when course was set for Vietnam across the South China Sea. The aforementioned drama unfolded on that first evening on passage when the Coxswain got an anonymous phone call that suggested there was a number of illegal pistols in the ship. The caller revealed the concealed location of one of them. It was duly found – a cheap .38 ‘Saturday-night special’. The XO, Ted Keane*, was informed who in turn advised the CO. Captain Loosli was under no illusions about the adverse impact this would have if such a weapon was uncovered by Customs or another authority on return to Australia. He immediately ordered Clear Lower Deck and a locker search of all junior personnel. A number of pistols came to light, primarily because an amnesty was declared – hand them in or ditch them over the side and there will be no repercussions. By the following day, the CO and XO were reasonably confident the menace no longer existed.

Several days later, during a lull in Gunline missions, the Petty Officer in charge of the Gunner’s Party reported to me that a quantity of small arms ammunition was missing from the magazine. The Cebu City Police Chief apparently had found his man. I consulted with the XO and we both agreed that the CO should be spared another heart-stopping report.

I had the greatest respect and admiration for the hard-working Gunner’s Party throughout the deployment but I suspected that one of them had to be the culprit. The team members had ready access to the magazine keys. All of the party members were stared down and grilled at length in turn by the XO, me and the Coxswain but we were unsuccessful in extracting a confession. In the absence of any incriminating hard evidence, the matter was put on the back-burner and eventually dropped, the Captain was left in peace and we got on with the business at hand with the main armament. After detaching from the Gunline for the last time, the Gunnery Log recorded the conduct of several recreational small arms firings during the fortnight’s passage home.

In a moment we will hear a replaying of our RAS song, Proud Mary, after which I will ask you to stand and join me in a toast to our ship and absent and departed shipmates, of whom there are many.

There was always some conjecture about how the ship adopted the song. I remember quite clearly. It came about during a Wardroom run ashore with the Captain to one of the naval base clubs following our first arrival at Subic Bay for the turn-over with Perth. A Filipino band was playing the Credence Clearwater Revival version of the song which many of us at the club that night had not heard before. Hal Thomsett turned to the Captain and excitedly declared, “That should be our RAS song!” We all agreed and the Captain said, “Make it so!”

Further Reading

Naval Operations in Vietnam, by Jozef Straczek, Sea Power Centre-Australia, available at https://www.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/naval-operations-vietnam

Crew List HMAS Brisbane 1st & 2nd Deployments: 1969 and 1971 available at http://www.gunplot.net/main/content/crew-list-hmas-brisbane-1st-2nd-deployments

Video of Interest

Royal Australian Navy: HMAS BRISBANE RAS and Breakaway featuring Proud Mary, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbLHS7Z6Tic

[i] * All deceased