- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Ron and Ian Forsyth

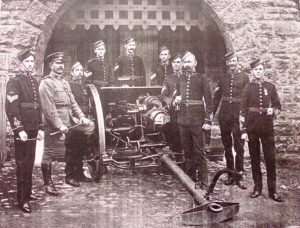

New information on the Fremantle Naval Volunteers, the only naval defence force to be established in the Colony of Western Australia, is documented in our recent biography of Captain George Andrew Duncan Forsyth, (1843-1894).1Forsyth was the founding commanding officer of the volunteers. The following is an abridged version of this story, with some additional material since discovered.

Under British law the Colony of Western Australian was not permitted to raise standing military forces. After the withdrawal of the British military’s presence from its domains in 1859 it did, however, like the other colonies, commission several official volunteer forces to defend its territory from foreign incursion. These forces provided a very low-cost option for the defence of the cash-strapped colony.

Between 1862 and 1878 twelve army units were set up in the colony; they included rifle units in Perth, Fremantle, Guildford and York and artillery units in Perth and Fremantle. Over the same period five of these units had faded and been disbanded, including the artillery unit in Fremantle. Each had separate identities and reported independently to the colony’s military commander. In 1874 a ‘1st Battalion, WA Volunteers’ was formed under an Inspecting Field Officer of Volunteers (then Lt Col R. A. Harvest) to allow these units to join together for training purposes at a company level.2

The establishment of the Fremantle Naval Volunteers (FNV) arose from a grass roots initiative led by the colony’s harbour master, George Forsyth (1843-1894). On 9 November 1878 he wrote to Lt Col Harvest proposing the establishment of a corps whose objective would be ‘to have a body of men, useful on sea or on land, and accustomed to the use of Battery or field guns, with the other drills, cutlass &c. as used in the Royal Navy’. He attached two resolutions to this effect, which had been adopted at a meeting of interested persons and which included the signatures of 37 men who were ready to immediately join such an initiative.

This was no ordinary list of names. It included many of the stalwarts from the shipping community in the port of Fremantle including mariners, ship owners, members of the harbour master’s service, water policemen and boat builders. Notably, though, it did not contain anyone with Royal Naval connections.3

This initiative coincided with growing interest by the Australian colonies and by London in the naval defence of the colonies, including renewed tensions between Russia and Great Britain. The attitude of the Colonial Office in London was that the naval defence of Fremantle was essentially a matter for the colony.4

The initiative also came some 30 months after Governor Robinson had commissioned the colony’s first mail steamer, SS Georgette, as a warship to pursue an American whaler, Catalpa, which was carrying six escaped political (Fenian) convicts from the colony to America. Armed with a cannon and under the command of John Stone of the Fremantle Water Police she chased the vessel but yielded the chase in international waters. This was one of the first times any of the Australian colonies had commissioned such a vessel – a prospect which caused concerns in London for decades as it did not favour the colonies raising their own warships.5

Lt. Col. Harvest strongly supported Forsyth’s initiative. In December 1878 he wrote to Governor Ord to seek approval to raise the corps, noting the petitioners were keen to commence drill at once. He advised he could supply an instructor for foot drill, an artillery man for gun drill and a couple of howitzers, and that the harbour master (Forsyth) could ‘manage boats’ and cutlass drills.6 Governor Ord agreed to commission the proposed FNV and to appoint Forsyth as its Lieutenant Commanding Officer. These acts were duly formalised in the Gazette of 11 February 1879:

Colonial Secretary’s Office Perth, 10th February 1879.

His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to approve the formation of a Naval Volunteer Force at Fremantle under the designation of ‘Fremantle Naval Volunteers’ and of the following gentleman officiating in the capacity stated opposite his name pending the result of the examination to be held before a Military Board assembled under the Government Notification of 20th April 1875.

George A. Forsyth, Esquire, Lieut. Commanding.

By His Excellency’s Command ROGER TUCKFD GOLDSWORTHY Colonial Secretary.

The FNV was also referred to variously as the Naval Artillery Volunteers (as had been proposed by Forsyth), the Fremantle Naval Brigade, the Fremantle Artillery, the Bluejackets, and the ‘Jack Tar Artillerymen’. It was described as a half-battery. It did not have a formal barracks but used some of the buildings at the Fremantle immigration depot as a gun shed, armoury and band room. It provided buildings, some weapons and items of uniform and a small ‘capitation’ grant for firing weapons.7.

Commenting on the foundation of the FNV in its edition of 22 February 1879 the Herald newspaper commented that:

It would of course be absurd to suppose that such a force would be of any service in case of a serious attack from a man of war bent upon effecting a landing, but the formation of such a company promotes good fellowship, begets submission to discipline and so fits men better to take their part in the world than they otherwise would.

Six months after its establishment, the existence of the FNV came under a vigorous challenge by a few members of the colony’s Legislative Council. The dissident councillors expressed concern about the amount of money being expended on the volunteer units and were particularly indignant that Governor Ord had not consulted their august body on the establishment of both the FNV and, in 1878, of the York Rifle Volunteers.

An account of this attempt to abort the FNV is contained in our book. In brief, in August 1879 the Council passed a resolution calling for the dissolution of the two new units and a substantial reduction in the budget for the volunteer forces as a whole. The members for Fremantle and York opposed the former proposal. On 3 September 1879 the Governor wrote to the council to advise that he was, accordingly, acting to disband the two corps but then went on to question that decision in the following terms:

It seems to be taken for granted that the Volunteers of the Colony would render no useful service in the first case; but this is a serious misconception. In the event of a war, the first efforts of an enemy would be directed to the capture or destruction of the shipping in our harbors and roadsteads, and of the stores and warehouses which contain the goods they transport. It is unlikely that any large force would be detached for this purpose, but serious and lasting injury might be effected by the agency of a single ship (similar to the ‘Alabama’ for instance), on the Port of Fremantle, if we were not prepared to offer any resistance to it, and yet such resistance could in His Excellency’s opinion be most successfully offered by the forces which are at present available for the purpose, viz.: The Pensioners, Volunteer Horse Artillery, Rifle Volunteers of Guildford, Perth, and Fremantle, the Pinjarra Horse if they could be brought up in time, and the Naval Artillery Volunteers of Fremantle; and of these the most useful by far in resisting such an attack would be the Fremantle Naval Artillery Volunteers. For the purpose of maintaining internal tranquility, if the necessity for so doing should ever arise, it is clear that the Volunteers supply the only reliable aid. The police number but 115 all told, and they are scattered all over the country, so that it would be impossible in many places to bring together in an emergency half a dozen of them. What efficient services may in such circumstances be afforded by a few Volunteers has been recently shown in a neighboring Colony, which they appear to have been able to save from very disastrous consequences. Of the advantage which military training brings with it, it is unnecessary here to speak, the only question which these considerations suggest is, whether the acknowledged advantages afforded by the maintenance of a force are compensated by the cost which it entails.8

A letter to the editor of The Inquirer and Commercial News from ‘a loyal subject’, published on 10 September 1879, addressed criticisms of the unit thus:

Amongst the recently formed corps is that of the Naval Artillery Volunteers, who have been drilling at the Port three nights a week for the last six months, at a cost to the Government of only one shilling per day for a drill instructor.

The expense of bringing field-pieces from Perth was paid by the corps, and the Commanding-officer (Lieut. Forsyth) paid out of his own private purse the cost of training a number of boys for a ‘drum-and-fife band’. Great praise is due to the praiseworthy Commanding officer of this company, and I am quite sure that the inhabitants of the Port would have heartily supported his efforts if appealed to. It was intended that the corps should have been drilled as a fire-brigade; also instructed in the rocket and mortar apparatus, to be available in cases of wreck. The advantages to have been derived from this company seems to be greater than any yet formed, and it is very much to be regretted that some of our legislators did not better inform themselves of the intended usefulness of the ‘Naval Artillery Volunteers.

These interventions must have been accompanied by considerable discussions and lobbying in the corridors as on 29 September the Legislative Council took the extraordinary step of rescinding its earlier decision on the two new units and of restoring most of the funding it had cut from the volunteers’ budget.9 It is notable that by this time the other Australian colonies not only had well-established defensive volunteer naval forces in place but also had some naval warships under commission.10

This move in the Legislative Council coincided with a few of the same dissident members heaping more angst on the administration over the position of the Inspector of the Volunteers. Despite initial scepticism and antagonism towards the FNV and the absence of any naval participation in it the force quickly developed into a robust and relatively proficient outfit. At a celebration of the first anniversary of the FNV in early 1880 Lt Forsyth said that he ‘could only say, though the Fremantle Naval Volunteers had not been put upon their trial, there was no doubt they would endeavour, if occasion required, to imitate the blue jackets of Old England’.11

In August 1881 the Perth Horse Artillery took their guns by road to Fremantle where they joined with the FNV on Arthur Hill and targeted two floating structures at 1,200 and 1,500 yards to sea. Twelve rounds were fired from each of the four guns. The Herald of 20 August 1881 reported:

The shooting was very good indeed, the target being struck fairly in the centre once, a piece of one of the boards being cut away for about two feet, while the canvas of the target was completely riddled with fragments of the shells from the Armstrong guns….

A Hazardous Life describes the participation of the FNV in several other encampments and field exercises, which attracted many casual observers and which the press reported on colourfully. In particular, it describes exploits at the annual Easter Encampments of the 1st Battalion, which had been instituted in 1882 by the then Inspector of Volunteers, Lt Col E. F. Angelo. Perhaps most notably, in 1884 the outnumbered Fremantle forces combined to defeat the other colonial forces, led by Angelo, in a spirited mock battle.

On 31 December 1881 the FNV’s strength was 4012 and in May 1885 it stood at 36 including two officers, with its 2IC, Wemyss, being promoted to lieutenant in that month.13

The Report on the Volunteer Forces for 1883-84 in the West Australian Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Council evinces the limited value of the FNV’s guns, recording:

The two six-pounder smooth-bore guns belonging to the Naval Artillery were manufactured in the early part of last century (1720 A.D), and reissued for service during the Peninsular campaign; they are consequently obsolete. Moreover, there are no limbers for them. They do not warrant expenditure. The Naval Artillery therefore are not armed in a way to be of use, except to sweep the shore with canister in the event of boat attack. There are in store at Fremantle two twelve-pounder howitzers of old pattern, also obsolete.

According to G. B. Trotter, in 1884 the FNV held in store 25 rifles, naval; 25 cutlass bayonets; and 25 old percussion muskets with bayonets. The old muskets and bayonets were believed to have been issued at the time the unit was established and were the issue arms until replaced by Sniders. The unit held about 12 parades a year and fired sixty rounds of ball ammunition from its carbines at target practice, which entitled it to a small ‘capitation’ grant.14 The limits on its weaponry may well have constrained the numbers in the corps in its early years. The Inquirer and Commercial News of 11 June 1884 published a complimentary account of the performance of the FNV, commenting: …there was prize firing by the Naval Artillery at the butts, when some of the men acquitted themselves remarkably well. In the afternoon some fine shooting was made, when the corps’ obsolete-guns were used on the gaol hill and by which good aim was taken at a beacon erected on the opposite point. Lieut. Forsyth is deserving of congratulation on the efficient state of his corps.

In 1885 the Colonial Office in London responded to requests from the governor to contribute to the defence, including fortification, of Fremantle. Its reply stated that this must essentially be provided from the colony’s budget but offered to provide the very modest contribution of two 6.5 ton guns, three 16 lb guns with carriages and limbers, and 100 rounds of ammunition for each gun.15

A select committee of the Legislative Council chaired by Colonial Secretary Malcolm Fraser advised the governor to defer any decision on this offer pending foreshadowed reports on the development of the harbour at Fremantle, which were intended to be made by an international marine engineering expert, Sir John Coode. He also foreshadowed that the colony’s volunteer forces may need to be reorganised.16 Coode’s report was not, however, delivered until 1886 and it seems the Colonial Office’s offer lapsed. It was not until January 1889 that the British provided two guns to the colony – several weeks after the FNV had been disbanded – see below. It is believed that these two ‘new’ guns, cast in 1813 and 1814 by H & C King, are those now on display in Kings Park, Perth.17

In the early 1880s Forsyth fell out of favour with the new colonial secretary, Malcolm Fraser, and with several shipping interests on the Legislative Council who wanted to replace him with someone who was more of their ilk. This was notwithstanding that Forsyth had run his ports’ operations across the administrations of three governors – including being appointed in 1879 as Harbour Master for the whole colony other than Albany, and the inaugural head of the colony’s Department of Harbour and Light – and had received numerous commendations for his performance in what were extremely challenging circumstances.

Forsyth faced several years of harassment at the hands of the Colonial Secretary and some members of the Legislative Council, the main episode of which was explained and dismissed by incoming Governor Broome in a lengthy despatch to the Secretary of State in London.18 Forsyth was, however, finally suspended from his public service positions in December 1885 in what were also contrived and contested circumstances, but on this occasion he earned the ire of Broome by refusing to resign his posts. A flurry of activity over the period from 15 to 21 December 1885 then occurred to remove him from his commission with the FNV.

On 17 December the FNV’s humiliated and indignant commanding officer pre-empted his decommissioning by writing to the Inspector of Volunteers, Lt Col E. F. Angelo, in the following terms:

As an Officer and a Gentleman I have felt it my duty to tender my resignation of the post of Officer Commanding the Naval Volunteers, which I hope will be accepted.

I deeply regret having to sever my connection with the Corps of which I may be justly termed the father. I was deputed by His Excellency Major General Sir Harry Ord KCMG CB to form the Corps, the first and only one of its kind in the Colony, and I struggled and fought against all kinds of difficulties to bring it up to what it is now, at great expense to myself, besides labour, time &c.

Perhaps the time may come, when Western Australia will want men like myself to defend her shores.

If this, my resignation, is accepted, I shall take the advantage of addressing the Officers and Gunners for the last time at the first Parade.

Forsyth’s resignation was notified quickly in the Government Gazette on 18 December 1885. He was not allowed to address the unit.

It is notable that all this disruption to the FNV came only months after the governor had received secret cables from authorities in the eastern colonies that put the government on high alert to the possibility of an invasion by Russia. A large public meeting in early 1885 had called for the strengthening of the colony’s defences. Such an invasion would obviously have been seaborne. As a precautionary measure the Governor had placed HMS Meda, an Admiralty survey schooner, in Gage Roads. New signals were developed in April so that Rottnest could warn the mainland of the approach of a ‘Foreign Ship of War’ and of ‘Suspicious-Looking Steam Vessels’.19

Although nothing came of this perceived threat it is interesting that the Governor and Forsyth’s detractors were prepared to jeopardise the operations of the FNV at such a time – and when no evidence had been provided of any lack of competence or diligence on Forsyth’s part with respect to the FNV.

Forsyth’s last service to the governor as commander of the FNV was on 27 November 1885 when it gave Broome a seventeen-gun salute on his return from a holiday in Melbourne. The Inquirer and Commercial News of 2 December reported: ‘the battery being well manned by the Naval Artillery, under Capt. Forsyth and Lieut. Wemyss’. Colonial Secretary Fraser was also in the welcoming party, which would have added to what must have been a bitter experience for its beleaguered commanding officer.

Forsyth was replaced as commanding officer of the FNV by his able and loyal port pilot of several years, Lt Frances (Fred) Wemyss. Wemyss had also been the pilot on Rottnest Island for a time.

It seems that enthusiasm within the FNV abated after Forsyth’s departure and in 1888 Wemyss recommended that it be disbanded and folded into a new artillery unit. On 18 December 1888 Governor Broome formally disbanded the FNV and renamed it the Fremantle Artillery Corps (FAC) in accordance with the following gazettal:

- His Excellency the Governor and Commander-in-Chief has been pleased to sanction the following changes in respect of the Fremantle Naval Artillery:

- The title of the Corps to be Fremantle Artillery.

- The uniform to be similar to that of the Perth Artillery except that the letters on the shoulder straps of the Non-Commissioned Officers and men will be FAV.

- The above alterations do not in any way affect the legal constitution of the Corps, nor the enrolment of the present members.

- Petty Officers will be given equivalent army ranks to what they now hold counting from the date of their original appointment.

By Command W.G. PHILLIMORE Lieut-Colonel Commandant Volunteer Forces Head Quarters Perth 18 December 1888.

The FAC thus ceased to have any naval connections. It was, like all the other volunteer units, issued with army uniforms and was run on army regulations and drills. Within two months of these changes, Lt Wemyss resigned his commission.20 He moved to Rottnest Island to take up the position of its pilot and, as had Forsyth, later become a master mariner/sea captain operating from Fremantle.

The disbandment of the colony’s only naval defence came at a time when all the other colonies were engaging more intensely with London on the issue of their naval defences. This had been a vexed issue for decades, with Great Britain not wishing to grant the colonies autonomy over naval forces and ships yet wanting them to contribute more to their naval defence through the Royal Navy – as very limited as that had been.

This was an especially irregular situation: not only did Western Australia have the longest coastline of any of the Australian colonies, it was the closest to perceived threats from foreign nations.

With the demise of the FNV the FAC had increasing difficulties with recruitment. In May 1885 its strength was 36.21By 31 December it had fallen to 3022 and in 1892, fell to 22. In October 1892 its designation was again changed, to No. 2 Battery, Field Artillery.23

After the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901 the naval brigades of all the other states of the Commonwealth of Australia continued to exist as separate organisations. In 1901 a committee was established to promote the raising of a new naval volunteer brigade in Fremantle24 but this was unsuccessful.

In 1907 all of the Australian naval volunteer corps were disbanded and the Commonwealth Naval Militia was formed. The Royal Australian Navy was not formed until 1911. In the meantime, Western Australia was the only state to have no naval defence corps.25

As far as we can ascertain the only extant artefact from the FNV is Forsyth’s sword, held by the Museum of Western Australia.

Notes:

1 Forsyth, R.K. & I.K., A Hazardous Life: Captain George Forsyth (1843-1894) Mariner and first harbor master for the Colony of Western Australia, published by the Maritime Heritage Association (Western Australia), 2019. Details: Publications at https://www.maritimeheritage.org.au

2 Wieck, G.T., The Volunteer Movement in Western Australia 1861-1903. Paterson Brokensha, 1962

3 Colonial Records Office: Colonial Secretary Inwards letters from G.A.D. Forsyth of 9 November 1878, annotated by Col. Harvest, and of 7 December 1878.

4 ‘The Naval Defence of the Australian Colonies to Federation’, 24 May 2008, published by the Naval Historical Society of Australia: https://navyhistory.au/the-naval-defence-of-the-australian-colonies-to-federation/

5 Naval Historical Society: op. cit.

6 Colonial Records Office: Colonial Secretary’s Inward Letters, 11 December 1878.

7 Wieck, G.T. op. cit.

8 WA State Records Office: Hansard of the Legislative Council of WA, 3 September 1879.

9 Hansard op. cit.: 29 September 1879

10 The Naval Historical Society of Australia: op. cit.

11 The West Australian, 6 April 1880.

12 The Daily News, 11 August 1882

13 Wieck, G.T. op. cit.

14 Trotter, G.B., Military Firearms in Colonial Western Australia: Their Issue & Marking. Records of the Western Australian Museum 17: 73-116 (1995)

15 Dispatch by Lord Derby to Governor Broome WA No. 44, 12 June 1885.

16 Report of a Select Committee of the WA Legislative Council on the defence of the town and port of Fremantle, 14 September 1885.

17 Fremantle Naval Artillery. Naval Historical Review, (1990) 21-8, 17-19

18 UK National Archives, Governor’s correspondence with the Secretary of State, WA, No. 31, Colonial Office document 4897, 8 February 1884.

19 Moynihan, J., All the News in a Flash, Rottnest Communication 1829-1979. (1988) Telecom Australia and the Institution of Engineers, Australia.

20 Wieck, G,T. op. cit.

21 Wieck, G.T. op. cit.

22 The Albany and King George’s Sound Advertiser, 29 October 1887

23 Wieck, G.T. op. cit.

24 The West Australian, 5 May 1900

25 The Naval Historical Society of Australia op. cit.