- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Midshipman Lloyd Skinner

Lloyd Skinner attended Melbourne Grammar School, where he discovered a passion for Australian political and military history. Shortly after completing secondary education in 2019 Lloyd joined the Royal Australian Navy and graduated from the New Entry Officers’ Course at HMAS Creswell, winning the Naval Historical Society Prize. Currently, as part of the Navy Gap Year program, he is undertaking work experience in Naval Intelligence Officer roles, a qualification he is interested in pursuing after finishing a tertiary degree in history and Chinese. In his spare time, Lloyd enjoys writing and reading about history and remains physically active, playing cricket, AFL and soccer.

…to truly develop as a nation, a strong Australia needed a strong Australian Navy. Australia’s future was dependent on maritime trade and its security lay in the protection of its sea lines of communication.

Vice Admiral Matthew Tripovich AO, CSC, RAN

Background

The formation of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) came to fruition not by a single factor but by a totality of factors, figureheads and events. Initially, the 1865 Colonial Naval Defence Act limited the parochial Australian colonies to possessing small, Admiralty-controlled vessels, each supported by the Royal Navy’s (RN) Australia Squadron in Sydney. Following Federation on 01 January 1901, and the unification of colonial navies on 01 March 1901 into the Commonwealth Naval Forces (CNF), growing Australian public opinion caused agents for change to emerge which championed an improved maritime capability through a strategic, modern and autonomous RAN.

Aim

The aim of this essay is to discuss the main factors that led to the formation of the RAN. It contends that the foundation of the RAN was spurred on by a confluence of geopolitical, social, strategic and economic issues, the absence of any of which could have delayed or prohibited its inception altogether.

For the purpose of this essay, the creation of the RAN occurred when King George V granted the title of the CNF as the RAN on 10 July 1911 and the arrival of the Australian fleet unit at Sydney Harbour in 03 October 1913. This essay does not focus on the nuances of the type and composition of the maritime force that differing individuals desired. Instead, it seeks to identify the holistic reasons that drove the transfer of the Antipodes’ naval defence from Admiralty control to the prerogative of the Australian Federal Government as well as the manufacturing of the Australian fleet unit.

Main point one – External control and ownership did not guarantee Australian security, hence increased desires for self-determination of defence policy

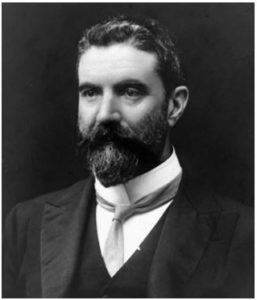

Primarily, calls for independent control of Australian naval assets were the culmination of changing international developments and doctrines that meant the United Kingdom was not a reliable security guarantor of Australia. The 1902 Naval Agreement, an arrangement where the RN had a subsidised presence in Australia, was becoming increasingly unpopular. Prime Minister Alfred Deakin was a robust opponent of this arrangement, displeased at the dearth of RN capital ships garrisoned at the Australia Station. He argued that ‘…we are without any visible evidence of our participation in the Naval Force towards which we contribute.’1 Additionally, the vessels of the Australia Station were outdated, having been described as ‘…a paddock to which old and worn out animals were sent in ignorance of their approaching end.’2

Compounding this was the fact that Australia had no control over this squadron. The arrangement involved significant monetary contributions from Australia for the fleet and its possible removal from the Pacific in wartime, with the result that ‘…there might be no defence at all when it was needed.’3

Deakin emphasised this in his Parliamentary address on 13 December 1907, stating that: ‘…the [Australia] Squadron in these seas may at any time be removed to the China or Indian Seas.’4 Bush poet Henry Lawson also reflected this tentative mindset Australians had toward their naval defence being controlled by the UK; he questioned, ‘…who shall aid and protect us when the blood-streaked dawn we meet?’5

Pivotally, the recall of ships at short notice was observable to Australians, being represented in the Boxer Rebellion from 02 November 1899 to 07 September 1901. The South Australian colonial vessel HMCS Protector, and a 500-strong force from the New South Wales and Victorian Naval Brigades, withdrew from Australian ports and joined the international coalition to subdue the anti-European rebellion in China, thence adding to feelings of vulnerability.

Further, the likelihood of RN vessel withdrawals from Australia had increased. A 1910 Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) report acknowledged a renewed requirement for greater concentration of British ships in the north seas becauseof German naval armament.6 As such, the requirement for autonomy on naval defence was because ‘…Australians feel no sort of confidence in Imperial guidance.’7

Deakin’s invitation of US President Theodore Roosevelt’s ‘Great White Fleet’ to tour Sydney during October 1908 demonstrated to Australians the attractiveness of an autonomous armada and aspirations for nationhood. The 16 US battleships in Sydney Harbour drew crowds of approximately 500,000, which ‘…to the supporters of local naval forces…was an inspiration,’ and garnered extensive enthusiasm for the formation of Australia’s own navy.8 This new mindset made Australians wish for defence self-determination, emblematic of the coming of age for the nation; as Overlack wrote, ‘…the visit of the American Fleet…elicited public sentiment that the time had come for Australia to provide for her own naval defence.’9 Significantly, Deakin’s posture was defiant toward the UK, who were not consulted on the tour, and was indicative of Australian interests for nationhood and independence which would come to fruition through their own navy.

Main point two – Sentiment toward the inadequacy of the CNF

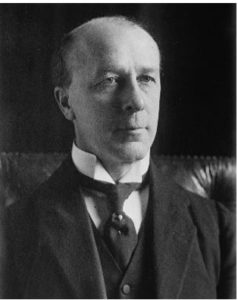

An inherent motivation for an Australian fleet was the desire for greater modernisation of Australia’s deficient seagoing capability. Under Admiralty control, the CNF, the status quo of Australian naval defences, comprised 16 vessels in 1905 with most having been commissioned prior to 1890.10 Likewise, naval manpower was underwhelming and in 1906, there were only 171 permanent service members and 1,081 in the militia.11 In a memorandum written on 22 September 1905, Captain William Creswell, the Naval Officer Commanding the CNF, pleaded for a localised Australian naval force, pinpointing the meagre capability of the CNF, stating that it was ‘…on the verge of collapse.’12 Professor David Stevens supports this observation, asserting that CNF ships, at their current state, ‘…were tired, old and inadequate even for training.’13

This insufficient sea power was believed incapable of defending Australia in the wake of Germany’s growing Pacific colonial outposts and the possible ‘…merchant warfare operations of the German East Asiatic Cruiser Squadron inQingdao.14 This culminated in Labor Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher’s stride to modernise Australia’s Navy, ordering two destroyers from the UK on 05 February 1909, a notable preliminary move in the formation of Australia’s navy.15

Main point three – UK wished for greater burden sharing over financing defence of its Dominions

In the midst of a naval arms race, Whitehall, the home of the British Defence Ministry, sought to adopt greater burden sharing and cost reciprocity with her Dominions in the defence of the British Empire, so the UK could better defend her own region. As the Anglo-German Naval Arms Race intensified, especially following the Reichstag’s assent of the ‘Fourth Bill’ in March 1908, in which greater German seagoing armament was instigated, a naval scare ensued in the UK.

Such led to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Reginald McKenna conceding to the House of Commons on 16 March 1909 that Germany’s expanse of their naval armaments industry would entail the Royal Navy losing numerical superiority by 1912 unless Britain increased its acquisition of battleships.16 The 1910 CID report also revealed that the growth of German naval power meant Britain required a greater concentration of forces in the North Seas for its own security. This ‘…increased the difficulty of making more requisite naval force available… in distance seas.’17 As such, Britain began to transform its views on the positioning of its naval stations and forces because ‘…the cost of maintaining squadrons of up-to-date warships around the globe proved prohibitive.’18 Consequently, McKenna presented a memorandum to the Imperial Conference delegation during 28 July 1909, contending that ‘British Dominions ought to share in the burden of maintaining the permanent naval supremacy of the Empire,’ namely through British Dominions establishing their own localised and independent navies.19

Consequently, as the Admiralty confronted these issues on naval defence, the ‘Fleet Unit’ concept was developed,creating a theoretical model for the existence of an Australian Navy. The concept, conjectured by First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, included ideas of ‘flotilla defence’ and the ‘battlecruiser concept’ and encompassed a fleet of an all-big-gun battle cruiser supported by several high-speed scouts that would create ‘tactical units.’20 Fisher’s presentation of the ‘Fleet Unit’ concept at the 1909 Imperial Conference signalled a modification of the Admiralty’s value for Dominion navies and their plausibility of existence. The concept neutralised Whitehall’s apprehensions on Dominion navies because they were ‘…small enough to be manageable in times of peace, but, in war, capable of effective action in conjunction with the Royal Navy.’21 Fisher’s proposition gained Parliamentary support in Britain given the long-term financial benefits of independently financed, manned and controlled Dominion fleet units. Therefore, the British Parliament was content to subsume a short-term financial cost in aiding Australia’s establishment of its own Navy through building its capital ships, assisting in sailor and officer training and handing over existing capabilities.

As Fisher identified ‘…we manage the job in Europe. They’ll manage it against the Yankees, Japs, and Chinese, as occasion requires out there.’22 Markedly, the RN was able to cease and withdraw its presence at the Australia Station with confidence in the RAN in peacetime and conflict.

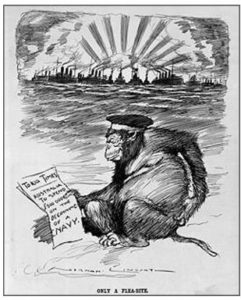

Main point four – public xenophobia and fears of a foreign invasion

Prominently, the national mindset of early Australia perceived that stronger sea power was intrinsically allied with defence of a ‘White Australia’ and protection from foreign invasion by Pacific colonies and nations. Events such as the sightings of the Russian gunboats and frigates: Afrika, Vestnik and Platon at Port Phillip Heads in January 1882 exposed Australia’s vulnerability to potential raids on ports and sea lines of communication.23

Public concerns for greater maritime defence were further compounded with the militarisation and expansionism of Imperial Japan. This was exemplified in its obliteration of the Russian Navy at Tsushima on 27 May 1905, and was where ‘…Japan became a threat to Australia.’24

Notably, the ‘White Australia’ policy, ever present in the national dialogue, only served to deepen the fear of foreign penetration, particularly from Asian nations. Hence, a ‘…xenophobic Australia observed with increasing concern the growing power of Japan’ increasing the calls for maritime defence.25 Despite the existence of the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Naval alliance, which enshrined Japan as a military ally, it ‘…did little to calm local fears’ because Australians recognised ‘…the fact that the alliance terminated in 1915 clearly demonstrated its lack of permanence.’26 The Admiralty’s withdrawal of the five RN battleships from the China Station following Tsushima, exacerbated these apprehensions, to which ‘the net effect was to confirm Australian opinion that the Pacific had been abandoned to the Japanese.’27 This added to the unease Australians felt about their security, and an Asian nation’s menace to it, creating a greater perceived need for stronger naval defences.

The growing German naval presence in the Pacific also contributed to the strategic rationale that Australia ought to expand and innovate its maritime forces. With Germany possessing several Pacific colonies and island outposts surrounding Australia, the ‘…distance from foreign attack was a rapidly diminishing factor.’28 Moreover, the German East Asiatic Cruiser Squadron, garrisoned at Qingdao, represented a significant threat. Its flagship, the SMS Fürst Bismarck, possessed four 9-inch and 12 6-inch guns as well as 6-inch armoured plating and bell turrets and overpowered all the capability in the Australia Station and CNF. As The Times highlighted on 02 February 1903, German cruisers were ‘…preying upon Colonial commerce and making descents upon Colonial ports’ in wartime.29 Especially, Australian ports and sea lines of trade and communication were ‘…now within striking distance of sixteen foreign naval stations.’30 This increasing foreign naval presence in neighbouring waters added to the justifications that Australia needed an extensive seagoing protection of its vulnerable and undefended export trade; valued at 64 million pounds in 1908.31 As such, support for an Australian Navy was both strategically and economically affirmed.

Conclusion

The formation of the RAN was spurred on by a confluence of factors, the absence of any of which may have delayed or prevented the outcome. Significantly, within Australia, the key agent that drove the establishment of the RAN was that ‘…national sentiment demanded more concrete assurance of protection.’32 This was due to xenophobia, fears of invasion, desires for improved defence and aspirations for self-determination. Yet, while these opinions were reflected in contemporary Federal Government and Section 51 of the Constitution enshrined the authority in the Australian Parliament to determine national defence policy, financial limitations meant the Admiralty held the final verdict. Once Whitehall found the strategic justification for the RAN, in Admiral Fisher’s ‘Fleet Unit’ concept, along with increasing German sea power in the Pacific, their concern that an Australian navy was a ‘misapplication of maritime power opposed to every sound principle of naval strategy’ was nullified.33 Markedly, Whitehall’s contentment to bear short-term financial burden in assisting Australia in establishing its naval fleet was due to this strategic justification affirming its existence, the long-term financial benefits to the UK as well as its favouring from public opinion.

Notes

1 Deakin to Governor-General, 28 August 1905. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

2 The Age, 21 February 1905. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

3 Overlack, P. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

4 Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, HoR Hansard, No 50, 1907, Friday 13 December 1907, p. 7510.

5 Australia’s Peril: The Warning. Verses quoted from Cronin, L., A Fantasy of Man: Henry Lawson Complete Works: 1901-1922, Lansdowne Press, Sydney, 1984. p 245

6 Report of CID 13 July 1910. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

7 The Age, 31 August 1908. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

8 Feakes, Henry James. White Ensign – Southern Cross. Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1952

9 Overlack, P. op. cit.

10 Defence Dept, CPP, 1906 in Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

11 ibid.

12 Captain Creswell’s Memorandum of 22 September 1905 for the Hon. T. Playford, Minister for Defence in Macandie, G. L. Genesis of the Royal Australian Navy: A Compilation. Sydney, Government Printer, 1949.

13 Stevens, David. The Royal Australian Navy: A History. Melbourne Oxford University Press, 2006.

14 Overlack, P., German Commerce Warfare Planning for the Australian Station 1900–1914, War & Society, May 1996.

15 The Australian Navy and the 1909 Imperial Conference on Defence. David Stevens, www.navy.gov.au/history /feature-histories/australian-navy-and-1909-imperial-conference-defence. Accessed 26 Feb. 2020.

16 The Australian Navy and the 1909 Imperial Conference on Defence. op. cit

17 Report of CID 13 July 1910. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, 2001.

18 Stevens, David. The Royal Australian Navy: A History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2006.

19 Memorandum by the Right Honourable R. K. McKenna, M.P., First Lord of the Admiralty on 28 July 1909 at an Imperial Conference on the Naval and Military Defence of the Empire in Macandie, G L. Genesis of the Royal Australian Navy: A Compilation. Sydney, Government Printer, 1949.

20 Lambert, N.A. Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 1999, pp. 92–94

21 Stevens, David. op. cit.

22 Letter Fisher to Esher, 13 September 1909, cited in A.J. Marder (Ed), Fear God and Dread Nought: Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher, Vol II, Jonathan Cape, London, 1956, p. 266.

23 Bulkeley, Dr R. I. P. ‘Ahoy – Mac’s Web Log – Early Visits of Russian Warships to Australia.’ Ahoy.Tk-Jk.Net, ahoy.tk-jk.net/macslog/EarlyVisitsofRussianWarsh.html. Accessed 04 Mar. 2020.

24 Harley, J. Alfred Deakin and the Australian Naval Story. In: Stevens, D. and Reeve, J. (Eds.), The Navy and the Nation: The Influence of the Navy on Modern Australia, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2005, p.303

25 Dwyer, Sheila. Sir William Rooke Creswell and the Foundation of the Australian Navy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK 2014.

26 Overlack, P. op. cit.

27 Stevens, David. op. cit.

28 Overlack, P. op. cit.

29 The Times, 02 February 1903. In: Reeve, John, and David Stevens. Southern Trident: Strategy, History and The Rise of Australian Naval Power. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards 2001.

30 Overlack, P. op. cit

31 Overlack, P. op. cit.

32 Stevens, David. op. cit.

33 Report of CID 25 May 1906, Confidential Memorandum ‘Australia’, PRO: Cab.5/1, p. 2. In: G.L. Macandie, Genesis of the Royal Australian Navy, Government Printer, Sydney, 1949