- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By David Payne

This is a continuation from Part 1 of this series which was published in the March 2021 edition of this magazine.

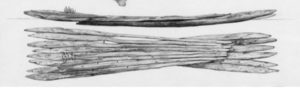

The dugout canoes from the top end of Australia are a significant contrast to their bark cousins covered in Part One of this story. They initially stand out with their strong base created by a heavy wall thickness on the bottom, that compensates for the significant loss of strength created by the cut-out along the top quarter of the cross-section’s circumference. It also puts weight lower down as the sides have a significantly thinner wall thickness, helping lower the centre of gravity, very useful on this long and narrow rounded hull shape that offers little from stability derived from width, unlike the bark canoes. It is also very much the opposite of the rolled bark canoe just discussed. Another feature not immediately obvious is that the craft is orientated to take advantage of the upwards taper in the trunk starting from its widest section at the base. This bottom or wider end is made the bow and the overall distribution of the volume then places more of it at the front, to support where the rig is located and where a hunter stands ready to harpoon quarry. It gives the correct displacement distribution relative to the weight distribution aboard the dugout so that hull topsides remain relatively level with the water.

Rafts

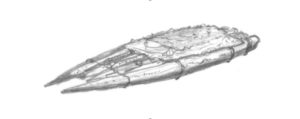

The Kimberley coastline is home to the kalwa or kawlum a two-part, fan shaped multiple log raft and a good opportunity to introduce some vessel design issues, in particular that key element; you have to have enough volume for the craft to float. It’s easy enough to visualize a log floating roughly half in and half out of the water. The submerged half is creating enough volume to support the weight of the log by itself, so the half that’s left above the water is free to allow the log to support some more weight. If you put enough logs together, you have enough volume in reserve to support a person, or even a couple of people as evidenced in images of these being used. The key is recognising how much volume is needed.

The construction is well thought out, pegged together to create a rigid fan of logs in the same plane, and its use as a two-part craft for hunting dugong or turtle is a highlight. Ideas like that today would be seen as a remarkable piece of lateral thinking.

The walba, walpa and walpo types from the lower Gulf of Carpentaria are different again, lashed together in what appears to be a more random fashion but still shaped to a particular arrangement. They are made largely from driftwood from the mainland, so the material is sourced and each craft is individually made from whatever is available in terms of twists and length. However by carefully placing them together so they intertwine, and then lashing them tightly, they form a rigid structure. In addition, the quantity of wood needed for enough volume and the need to have sufficient width for stability is also accounted for in the shape. The long walpo with its strong triangular shape is a very capable craft, and no two craft will be identical in how the logs are positioned.

Double and Single Outrigger Canoes

Similar features already noted in the dugout construction show up the many outrigger craft with solid wood hulls.

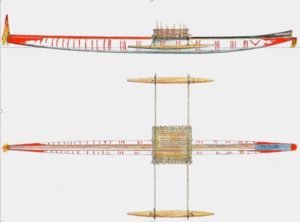

The craft from Torres Strait are the biggest and most sophisticated. The main hull is made in the Fly River region of PNG by their community. Their custom is to have the shape orientated so that the bottom of the tree becomes the bow end, and then the shape gradually tapers aft to become thinner, perhaps not by much in some trees, and again the cut-out at the top is compensated by a heavy wall thickness on the bottom. In this case the forward concentration of the hulls volume distribution requires the main structure across the hulls to be placed forward of the middle so that the hull will sit level in the water, and does not need an awkward distribution of the paddlers to compensate for the weight and bring it back to level trim.

Outriggers such as Kia Marina show very sophisticated construction and embellishment. In contrast the Gunggangji community’s outrigger from Cape Grafton in Queensland has some similar details, but initially seems much simpler in some respects, then shows a good understanding of rigidity when looked at in detail.

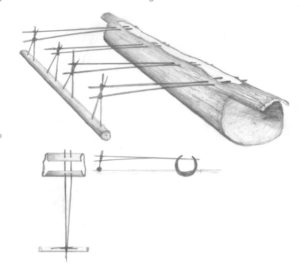

The squared off ends and single outrigger simplify the basic elements of the structure. Looking down in plan view, the twin poles at each strut are spaced apart as they enter the main hull and this triangulation, repeated at each strut pair stiffens the fore and aft connection between both hulls significantly, otherwise a diagonal brace might be needed to stop the outer hull breaking off in waves. Triangulation is again used on the posts at the connection of the strut to the outrigger hull. In the end view, the potentially weak 90 degree joint to the vertical members of the outrigger hull is stiffened by lashing the struts above and below their crossover point. The bracing effect of triangulation is working in a number of ways, all done with an economy of material and connections.

This is the furthest south the outrigger canoe comes, and bridging the span between the Torres Strait and these canoes are versions with more shape to the main hull, and are both single and double outrigger versions. The ends of all of these feature a platform to stand on for spearing dugong or turtle.

The Cape York canoes on the Gulf of Carpentaria coast side are quite simple. The dugout hull has two cross beams, curving downwards across the hull, and they are attached directly by simple struts to narrow floats made of a branch or trunk of a light tree. The right proportions of beam and volume provide quite adequate stability, and are a big improvement over the stability of the unsupported dugout hull.

The Environment and Sustainability

First Nation communities have long practiced a sustainable lifestyle. ‘Country’ is a foundation of their society and care and respect for the country is a primary element in their everyday life.

Two different Cape York double outrigger canoes

They practised agricultural methods to farm plants and animals, built channels and dams and undertook other ‘civil engineering’ projects across the country. Bruce Pascoe in Dark Emu records all of this and more in great detail.Resources were managed in various ways to ensure they were available each season and available for the next generation. Food was gathered at the right time of the cycle, and generally only what was required was taken, leaving it to grow again for the next season. This process often applied to fishing and hunting. Nothing was overworked, and a key principle to note is that resources were taken when it was the right time. Resources were not artificially engineered to be available at another unnatural time, so activities, trade and movement was based around when items were abundant.

Fire was commonplace in many parts of the landscape, and nature had evolved to take advantage of it. Many seeds needed fire to break open their protective covering that saw them through the dry times, and then they would sprout. The communities saw fire as a resource and tool rather than a danger, it was nurtured, stored and taken with them as they moved over their country. They used fire as a tool to help nature. Done in a careful manner, it was used to clear and regenerate areas before they became over-grown, and any significant fire in these situations would do more damage than good.

This sustainability was also energy efficient; time and effort were not wasted on trying to collect or ‘create’ something not easily available, and complementing this was the fact that only the minimum of energy was needed to collect things that were easily available in the normal cycle of life.

In Dark Emu’s acknowledgements, when referring to Bill Gammage’s book-The Biggest Estate on Earth, Bruce Pascoe writes the following. P231/232 ‘Not a wilderness, not a land peopled by wanderers, but a managed landscape created by enormous labour of people intent on creating the best possible conditions for food production’.”

This can be applied in paraphrase to the watercraft. They are not a haphazard series of basic craft that drifted with the current and were just another artefact, they are a series of capable, navigable craft engineered sustainably from theirregional materials to deliver a vehicle for the benefit of the many communities who built them.

A good example to show this are the tied-bark canoes. They were capable enough to be used on flat water lakes, rivers, estuaries and harbours as well as along the coastline, crossing to islands or just fishing out beyond the cliffs and beaches in open seas.

To build one was not a random task. Amongst the over 300 species of eucalypts, there is a very limited number of species that give the right bark, probably just a handful. In addition, there are right times in the year to cut the bark, which is when the sap is rising, often in association with damp periods. There can even be a better side of the tree to take it from. And ideally the tree to be used is big enough so that when the bark is cut, a reasonable portion can be left on the tree leaving a continuous connection of roots to the leaves for the tree to live on. This then reduces considerably the actual number of trees available to build canoes, and patience is needed to wait until the right time of the cycle to cut the bark. And that cutting process often involves ceremony that continues the respect needed for the resource and for the elders who have passed on the knowledge that enables them to build the canoe.

The ’plan’ for a watercraft is not a drawing, it is knowledge that is passed on and it is more than just the elements of the structure, it’s a handbook of the whole procedure from managing the resources, collecting them, creating the shape, its use and maintenance.

Sustainability includes eliminating wastage of materials and waste products that build up. The biodegradable nature of the materials used means the canoes simply return to the earth at the end of their usable life, and the wood and fibre canoes were clearly matched to this. Their usable life was also managed, care was often taken to store craft correctly so they maintained their structure as best possible, and they were repairable. They were valuable items to their owner and their community, so the effort spent in making one was respected by care taken to extend their life to a reasonable timespan.

Chronology of Evolution

It is difficult to put reliable dates on how old these craft might be in regards to the known length of time the country has been occupied by man. For many years this occupation was put at 40,000 years, but recent advances in archaeology have moved that to around 65,000 years, and maybe more. It is understood they came here with at least one open-water sea crossing or passage between the Indonesian islands and mainland Australia, then joined to PNG.

Therefore they had a maritime vessel background to their story of arrival, but what type of craft that was is speculation, as is the reason for the first voyages.

The type is somewhere back in the chain of craft starting with simply adapting a log or other material that helps a person float, through to rafts that took advantage of currents or prevailing conditions to go in that direction, then on to building a deliberately designed craft that could be navigated in any direction regardless of the conditions. It could be said that this final point marks the origins of a boat, something that was built and used with purpose and control over the materials and the way it was propelled and navigated.

So, if we go back to the elegant and simple yuki for example – there is no date that can be put on its development, but perhaps it can be placed in this evolutionary chain, with the suggestion that as a type it is very close to the origin of a true boat and would sit comfortably amongst the earliest form of boats ever built.

It has been deliberately shaped and manipulated with simple methods that respond to the capabilities of the materials; it has minimal but the essential structure needed for strength, and respects structural or engineering requirements; it shows an appreciation of the waves and other features of the water it is to be used on, and this process combines into a shape forming a boat that can be used as desired, it is not navigated totally at the whim of the current and conditions, it can be manoeuvred and taken where the person wants to go.

If this is accepted, then we are looking at the yuki and other Australian Indigenous watercraft as examples of the earliest stages in boat design, and this suggests a fascinating big picture thought.

In the mid-1990s the discovery of the Wollemi Pine in an almost inaccessible Blue Mountains gully not far from Sydney was hailed worldwide as an immensely important find. Here was a very early form of tree from a past geological period that had been thought extinct and only studied from fossils, but was actually still existing in modern times beside contemporary trees.

These many Indigenous watercraft types should be given a similar status, amongst the earliest of boats and still in use in modern times. Australia can be proud to have both ends of the vessel design spectrum in use. We can design and build outstanding modern racing yachts, motor craft and commercial craft that are all at the leading edge of contemporary design and technology, and still practise the craft of building properly engineered, sustainable boats that are the beginning of this evolutionary pathway.

The author

David Payne retired in late 2020 after a long career as a yacht and small craft designer, including over a decade serving as the curator for the Australian Register of Historic Vessels at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney, Australia, from 2004 through to 2020.

The ARHV register has many early examples of Indigenous watercraft listed from craft located in museum collections throughout Australia or held in international institutions. Through the associated research into the different craft and their types David developed a separate study of the many types of watercraft used by Indigenous communities throughout Australia and the Torres Strait.

David has combined his design background with this extensive research to undertake practical work as well. He has made a series of drawings of the various watercraft, constructed models and also built full-size examples in bark and plywood.