By Commodore Bob Trotter OAM RAN & FIEAust (Retd)©

Bob Trotter is an engineer and submarine specialist. He retired from the RAN in 1998 and after a period with Austal Ships facilitating its initial entry into the Australian and International Defence markets, he became a fully committed volunteer in the quest to find Sydney. He was a Member and Director of the FSF from 2002 until 2011 and, for his contribution to the successful search he was awarded a Medal in the Order of Australia in 2009.

Bob Trotter is an engineer and submarine specialist. He retired from the RAN in 1998 and after a period with Austal Ships facilitating its initial entry into the Australian and International Defence markets, he became a fully committed volunteer in the quest to find Sydney. He was a Member and Director of the FSF from 2002 until 2011 and, for his contribution to the successful search he was awarded a Medal in the Order of Australia in 2009.

High above the City of Geraldton in Western Australia, at the National HMAS Sydney II Memorial, the figure of a woman stands with her gaze fixed patiently on the horizon; she is waiting for her man; grieving for her lost father, husband, brother, son; hoping that her ship will be found.

Remarkably, she is eerily prophetic of the search for Sydney because she stared down the exact bearing of the wreck for seven years before its discovery by the Finding Sydney Foundation (FSF) some 200 km to the North West. Regrettably, only hindsight provided this knowledge as serendipity did not play a part in the search for Sydney rather, the discovery was a triumph for commitment, persistence and science by a small group of ordinary Australians employing world leaders in deep water search operations and technology.

| Figure 1: The Waiting Woman, National HMAS Sydney Memorial, Geraldton, WA |

A Legacy of Disagreement

Sixty years after the loss of Sydney, the FSF was born out of its members frustration with the entrenched division amongst researchers and their emphasis on divining what happened, why and by whom rather than to questions of where either of the two ships might lie. The FSF knew that the ship could be found and decided to do it, in the lifetimes of the remaining close relatives of those killed.

The Chief of Navy (CN) during the critical years of 2002 to 2005, Vice-Admiral Chris Ritchie AO, understood that no two of the organisations that claimed to have a theory on Sydney’s location agreed and he therefore believed that none was worth pursuing. The Joint Committee of Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade had enquired into it without any real conclusion and claims as to special knowledge about Sydney kept arriving in the CN’s and the Minister’s office; in Chris Ritchie’s words “the whole thing was going strong but going nowhere”.

Ritchie’s predecessor, Vice-Admiral David Shackleton, had announced that the outcomes of a Navy-lead Search Definition Seminar at the Western Australian Maritime Museum in November 2001 did not provide a suitable basis for an official search for the wreck. Indeed, the optimism that the seminar outcome could mean a search getting underway was dampened by a tragic lack of willingness among historians and researchers to reach a consensus. Shackleton’s clearly stated position was that there was no direct evidence that could provide a search datum for the wreck of Sydney. However, the soon-to-be FSF dismissed what it thought was the Australian Institute for Slowly and Painfully Working Out the Surprisingly Obvious (apologies to author, the late Douglas Adams ‘Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’); it believed that the datum was the wreck of Kormoran and, moreover, there were many reliable eyewitness accounts to her position and, within her visible horizon, to the last moments of Sydney.

Achieving Government Support

To obtain the Government’s support, either moral or financial, the FSF’s aim was to convince the CN that a plan proposing a high probability of finding Kormoran would succeed and become the key to finding Sydney.

The starting point was a belief that the Kormoran survivors told the truth as they were rescued and later under interrogation. They would have had no reason to lie about the position of their ship, especially with shipmates still unaccounted for and no previous investigations had established any such reason, even allowing for obfuscation that might be expected from a Prisoner of War.

The FSF had defined the conditions for a successful search during 2004; indeed, the work of Australian scientists had pinpointed the positions of the wrecks to 2.7 and 9 nautical miles from where the wrecks of Kormoran and Sydneyrespectively were found by the 2008 expedition. It had confidence in its capacity to run a search operation in very deep water as the FSF membership had an extensive pool of managerial, legal, technical and scientific expertise in ocean operations. Regrettably, Government and large donor corporations did not share such confidence in this small group of Australians.

During 2003 the FSF was introduced to the work of David Mearns, a UK-based professional whose credentials included success in finding many deep-water wrecks, most famously that of HMS Hood. Mearns was carrying out research on Sydney, parallel to that of the FSF, by review, test and reinterpretation of existing information. After some discussion and meetings, the FSF concluded that there was some merit in loose cooperation with Mearns, but his was a commercial interest and his input was not essential to a successful search.

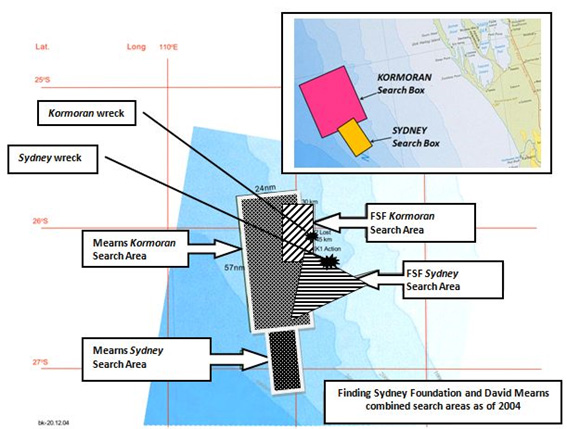

A closer FSF/Mearns relationship was encouraged by the CN, VADM Ritchie who, when Captain of HMAS Brisbane in the Gulf of Oman in 1990, knew of Mearns finding the MV Lucona in very deep water, claimed to have hit a mine, and proved it to be a murderous insurance fraud. During 2003 Mearns had called on Ritchie about Sydney and it became clear to him that FSF and Mearns had defined likely search areas that were contiguous. Ritchie mused that if the two cooperated the Government might support such a venture as for the first time two reputable organisations were sensibly in agreement based on reasonable information (See Figure 2).

FSF and Mearns agreed that he would be employed to assist it in refining the search area and to be the Search Director for the on-water phase. In June 2005, the Government formally advised the FSF that based on the arrangements with Mearns, it supported the FSF Plans, albeit that it did not include any funds at that time.

The Confidence in FSF Research Outcome

The FSF’s confident search area for Kormoran was based on research carried out by Professor Kim Kirsner and Dr John Dunn both of the University of WA. Kirsner is a world leader in the field of Cognitive Science and Dunn a Mathematical Psychologist. Joined by the work of experts in oceanography and search and rescue methodology, they applied their research of the Kormoran survivors reports by undertaking mathematical analyses of them and integrated the results with the likely origins of drift objects from Kormoran that had been recovered during November/December 1941.

Cognitive Science, very simply, is useful when memory and decision-making influence interpretation of evidence. For example, evidence from the Kormoran survivors was obtained within 7 to 21 days from men in their domains of expertise (e.g., navigation); the information they provided was critical to their survival and, significantly, the information was elicited by domain experts, i.e. Australian Naval Officers, some with considerable combat experience. By contrast, many oral history reports involved remote events over a period greater than 40 years and their relevance to the loss of Sydney could not be determined with any confidence.

The baseline for the Kirsner/Dunn work and the resultant FSF approach was provided by an Oceanography Workshop initiated in 1991 by Kirsner and Dr Michael ‘Mack’ McCarthy of the WA Museum. Outcomes of the workshop included oceanographic arguments or models developed by Australian professionals in their respective fields. Sam Hughes a Search and Rescue expert, Steedman, McCormack, Penrose and Klaka, Oceanographers all, identified positions and areas but the search areas associated with their work were large, up to 7,000 sq nm.

Refining the body of knowledge from the Kirsner/Dunn work was undertaken in three phases between 1991 and 2005 as follows:

- Research using a Search and Rescue model by SAR expert Sam Hughes, provided positions that were approximately 20 nm from the wreck of Kormoran.

- Cognitive reconstruction of the Kormoran survivor’s reports supplemented by subjective integration, Kirsner and Dunn (1998) provided a target 7-10 nm from the wreck of Kormoran.

- Further cognitive reconstruction of the Kormoran survivor’s reports supplemented by an objective mathematical model provided a target just 2.7 nm from the wreck of Kormoran.

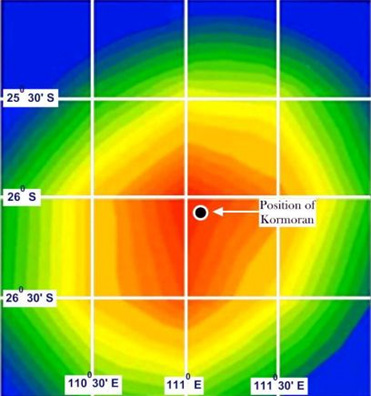

The summation of the professional products of the 1991 Workshop, later work by the Oceanographers and the progressive refinement above is illustrated in Figure 3 which is a mathematical presentation of the contours of increasing confidence toward the centre and showing the actual position of Kormoran.

(from Kirsner & Dunn 2004)

Under the working relationship established with David Mearns between 2003 and 2008, all the above FSF research products were provided to him.

Adding the Mearns Dimension

As indicated above, Mearns was not part of the initial plans worked up by the FSF between 2001 and 2004 but joined with it later to raise the Government’s confidence in the FSF and, of course, because he was demonstrably at the top of his profession as a wreck hunter, especially for the on-water work. His work is fully explained in his book “The Search for the Sydney”.

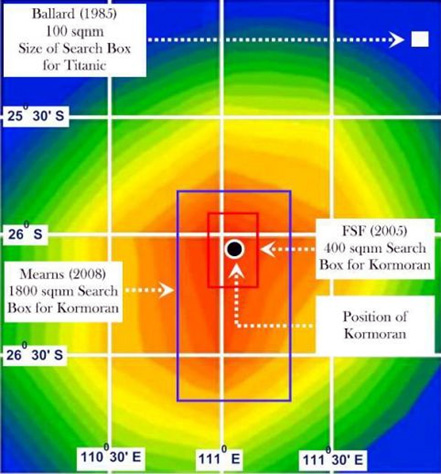

Mearns’ approach to defining a search area generally involved the navigational possibilities provided by interpretations of the coded dictionary used by Kormoran’s Commander Theodore Detmers to record his Battle Report, by new primary documentation uncovered by him in UK historical archives and, by discussions with octogenarian Reinhold von Malapert, Kormoran’s Radio Officer. Figure 2 shows the search areas that he had formed by 2004 which, although to the West of the FSF, were sufficient to provide mutual corroboration of each other’s work. In 2007, the results of FSF-funded studies by the Department of Meteorology and by Dr David Griffin of the CSIRO Marine & Atmospheric Research Division added simulated trajectories of drift objects from Kormoran to provide a confidence factor as to their likely origins. Accounting for all the above Mearns final 95% confidence level search area for Kormoran was 1800 sq nm. It is shown at Figure 4 which includes comparison with the FSF 2004/5 area.

The Result

The sonar search operation lasted thirteen days, eight of which were down time due to weather and equipment failures, but wonderfully for all concerned both HSK Kormoran and HMAS Sydney were located within five days of active searching.

The subsequent visual inspection of the wrecks provided 1,430 still photographs and 47 hours of video comprising a compelling and confronting record of the blows inflicted on each ship and the likely last moments of both.

From simple observation of the wrecks of Sydney and Kormoran it is quite clear that most Kormoran survivors told the truth under interrogation in 1941, a satisfying conclusion to the FSF belief that underpinned its research.

Figure 5 & 6: “..some of us left the ship over the bow..”; “…I saw a direct hit on the second turret and its roof blow off..“

Epilogue 1

Finding the wreck of HMAS Sydney II solved an enduring mystery, closed a chapter in Australia’s history and, importantly, brought closure to the families of the men killed on both sides of the conflict. Accordingly, it also brought immense personal satisfaction to each of the five members of the FSF that their commitment and persistence in pushing the results of a scientific approach had paid dividends. They remain confident that an entirely Australian lead operation would have been as successful as early as 2004 or 2005 had the Australian Government shown more confidence in the FSF abilities. That it took the addition of an overseas professional to convince Government could be a matter of regret was it not for the fact that in doing so the FSF got the support needed to achieve its objective of finding Sydney.

David Mearns published his book (The Search for the Sydney – How Australia’s greatest maritime mystery was solved) in 2009, purporting to be the ‘Official Record’. Regrettably, although permitted to do so under the terms of his contract with the FSF, he did so without consultation with it regarding content. Consequently, it reflects his own impression of his role in finding the wrecks.

Members of the FSF published a book (The Search for HMAS Sydney: An Australian Story) in 2014. It included inputs from all stakeholders such as Government Ministers, telling the full Australian story of which David’s role in this Australian project was one important part in the final phase of a decades-long process involving many players.

Closing this chapter in history opened and closed another by bringing on almost immediately a successful search for the Hospital Ship Centaur in the area described by her Navigator. Her discovery confirmed, as did that of Kormoran, the common sense involved in accepting the truth offered by domain experts present at the time of such tragedies.

Epilogue 2

The 2008 discovery of the wrecks captured the imagination of two young researchers who dreamt and then lived their impossible dream — bringing what lies in total darkness on the seabed nearly three kilometres beneath the waves and 200 kilometres from the coast to the surface for all to experience.

This had never been done before. Needing a state-of-the-art ship and its crew, the most modern of underwater vehicles, state-of-the-art visual modelling and reconstructive imaging technology, an unheard-of array of mounted lighting and cameras, and the support and services of some of Australia’s leading scientists, maritime archaeologists and historians, they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

So, during April/May 2015 a four-day joint Curtin University & WA Museum expedition to the shipwrecks accumulated approximately 50 terabytes of data from two underwater remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), each equipped with seven digital still cameras and two 3DHD video cameras. By 2020, the end state will be a stunning virtual museum exhibit for people to experience at first hand the unreachable wreck sites.

There are almost 700,000 images to process and analyse – along with 3D multibeam sonar surveys of each wreck site – which will be used to create the 3D models, an immense ‘Big Data’ task which has put the University at the forefront of immersive visualisation technology. Google ‘Curtin University Hive’ for further descriptions.

Meanwhile, the WA Museum has produced an excellent book of the project “From Great Depths”. It features the results of the astounding success of the expedition, presenting incredible underwater photography and fascinating new discoveries, brought together with inspiring and heartrending personal accounts of wartime service by men in both ships.