First published in the December 1994 edition of the Naval Historical Review

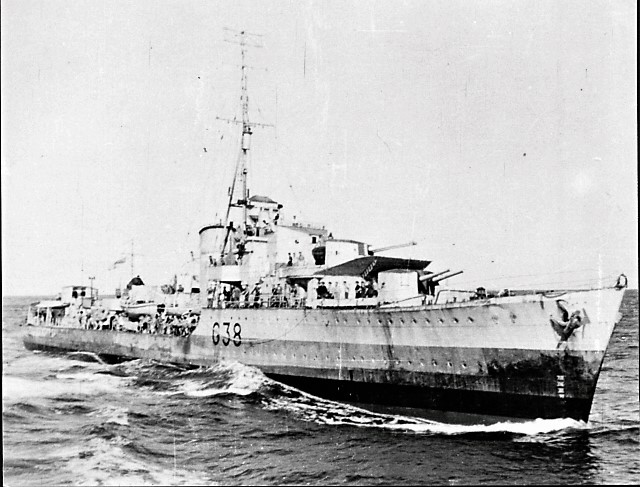

On 12 September, 1945, HMAS Nizam, a fleet destroyer of the 7th Destroyer Flotilla, sailed from Tokyo Bay, where she had been since 30 August, in company with HMNZS Gambia, for detached duty with units of the US 5th Fleet at Wakayama, some 300 miles to the south. It was expected that allied Prisoners of War from inland Japan – including Australian and New Zealand servicemen – were to be transported by rail to Wakayama and the two Dominion ships were chosen to provide welcoming parties for their countrymen.

It was our first night at sea in peacetime since 2 September, 1939, and the pipe “Place oil and steaming lights” puzzled all but the oldest hands onboard.

The two ships were met off the entrance to Wakanoura Wan by an American Destroyer Escort (DE) who led us into harbour via a safe channel with had only recently been swept.

The huge USN hospital ship Consolation appeared to be taking up Nizam’s anchorage as well as her own, and when we anchored we seemed in very close proximity to her. Our officers invited several USN doctors and nurses to the Wardroom after dinner and we had a very pleasant evening.

The weather deteriorated on 14 September – windy and raining – but Nizam sent a group of officers and chief petty officers ashore to meet the returning POWs. To the delight of both parties, survivors from HMAS Perth were amongst the Australians. When it was realised that there were many more Australians than had been expected, Nizam’sreception party was greatly increased.

I went ashore to greet my old shipmates from Perth with whom I had commissioned that ship in Portsmouth in July, 1939. Next day, they came off to Nizam to attend their first shipboard Sunday Divisions and Prayers for more than three-and-a-half years. A very moving occasion. The USN organisation for the reception of the Released Allied Military Personnel (RAMP) was excellent.

Warnings of an approaching typhoon were received on Sunday, 16 September. The Captain of Gambia and his meteorological officer kindly came over to Nizam and briefed me with all the information they had. They predicted that there was a chance of the typhoon recurving and passing over Wakayama. Observing that we were in a reasonably safe anchorage and that access to the open sea was restricted, the Captain of Gambia advised that Nizam should stay at anchor in harbour. Even at that stage, with the centre of the typhoon some 800 miles away, a light swell was evident.

The weather became threatening next day, 17 September. The wind increased markedly at about 1600, and I ordered immediate notice for steam on both boilers (capable of developing 40,000 horsepower), and set an anchor watch, i.e. parties closed up on the forecastle and in the wheelhouse, with the Officer of the Watch on the bridge (and the Captain in his sea cabin!). The ship was yawing at her anchor but I decided not to drop the other anchor underfoot because of the difficulties of recovering both anchors in an emergency with only the one capstan available. She lay with six shackles out in eleven fathoms. By 2200 the wind had increased above gale force. Recordings taken in USS Floyds Bay recorded an average force of wind between 2100 and 2200 as 50 knots with gusts to 65 knots. During the height of the typhoon she recorded an average of 65 knots with gusts of up to 85 knots. (About 140 mph).

At 2230 Nizam began to drag. The wind and rain had reduced visibility to less than 200 yards and when one showed one’s head over the front of the open bridge, the rain and spray, driven almost horizontally, made it impossible to keep one’s eyes open for more than a second or two. It was obvious we were dragging because Consolation, with all her upper deck lights on, appeared through the murk as though she was steaming away from us up to windward! Dragging was confirmed by leadsmen closed up on the forecastle and quarterdeck, although it was hard to pass orders and receive reports from them because of the screaming of the wind. On the forecastle, the Gunner’s plastic raincoat was literally torn from his back, leaving only the neck and the reinforced front with its buttons – which gave little protection!

Protected as the harbour was, the wind whipped up a short steep sea which on more than one occasion swept the forecastle. The largest roll recorded in the engine room during the night was thirty degrees! (Report of Proceedings, HMAS Nizam for month of September, 1945). Several small USN vessels – mostly minesweepers – of which there must have been 30 or 40 in the harbour, had weighed anchor after dragging and were steaming at slow speed round USS Consolation. With her bright lights, she was a guiding beacon and certainly lived up to her name. Rather like moths circling round a candle, I thought.

Even at very close range, the big ship’s outline was not visible at times and when she did come into view, through the stinging rain, it was an awesome sight to see her yawing through about sixty degrees, heeled over by the force of the typhoon. With “some hundred fathom of chain out” as the Americans reported later, she dragged a couple of cables during the night.

As for Nizam, when her dragging was obvious to me, we weighed anchor and after turning the ship, I endeavoured to find an anchorage further up to windward where I hoped for some shelter under the lee of the southern shore of the bay. But as soon as we stopped and dropped anchor, we were swung broadside to the wind and there was no chance of the anchor holding. There was also less swinging room between us and the many small craft seeking the same shelter. We blew down wind seeming to miss numerous small craft by inches and I tried a further time to anchor. Again it was impossible to hold the ship in such a wind. By this time I was on a lee shore and reports from leadsmen were not encouraging. I decided to weigh anchor and get out to sea – or at least out of the small harbour and away from the dozens of small craft milling round me.

I gave the order to weigh but nothing seemed to be happening on the forecastle except the occasional shudder and groan from the capstan: Finally I got the message that the capstan had jammed. No inkling of how much cable was out or whether the anchor was aweigh or not. And one could not blame the forecastle party – how they could see anything at that stage was a miracle. I decided that desperate measures were called for if we were not to end up on the beach. I passed the order to “clear the forecastle”, determined to go ahead and part the cable if necessary. To turn the ship into the wind on this occasion, I had to order “Slow Ahead” on the weather engine and “Half Ahead – 180 revolutions (20 knots)” on the lee. She responded splendidly – perhaps the engine room crew had sensed the urgency – and with less water under her keel than I chose to know about, we dodged the swarming small craft and steamed out of Wakanoura Wan into the more open waters of the Kii Suido. (The entrance to the Inland Sea).

Gambia and some larger units of the US Fifth Fleet, still at anchor (I hoped!), came into view and I spent the rest of the night steaming up and down the line of the big ships, emulating the small craft circling Consolation. Gambia told me later that she, too, had dragged, but not dangerously. It was estimated that the centre of the typhoon passed 405 miles to the west of Wakayama.

The mystery of the seized capstan was revealed later. While weighing, the anchor had twisted and both flukes had caught under the forefoot of the ship. The poor capstan then, was trying to haul the forefoot up through the hawsepipe. No wonder it refused duty!

No dawn, grey, windy and wet as it was, ever looked so beautiful to me! It had been an “all nighter” on the bridge, but I seem to remember that I was more worried about grounding than colliding with the small vessels swarming round – after all, I was bigger than them.

We returned and anchored in the harbour at 1130, and by sunset it was beautifully calm. It was a magnificent evening with a glorious moon to mock us.

My “escape” did not precipitate any diplomatic coup such as that of Calliope in 1889, but I knew how her Captain felt. I imagine that his satisfaction was the more in the saving of his ship than in the assistance it gave to his political bosses in Whitehall in annexing Western Samoa.

Footnote:

HMS Calliope, the third ship of that name in the Royal Navy, was a third class cruiser of 2,770 tons, launched in 1884 at Portsmouth. She became famous as the only survivor of seven men-of-war (six of them belonging to other nations), lying in the harbour of APIA BAY, SAMOA, when a terrific hurricane (sic) struck on 15 March 1889. Her Captain, Henry Coey Kane, fought his way out into the open ocean and saved his ship. The other six men-of-war were blown ashore and wrecked. (The remains of their boilers were still visible when HMAS Australia visited Apia in March 1935 – WEC). Captain Kane ascribed his escape to the admirable order in which Calliope’s engines had been maintained. A special medal was struck by the Admiralty to commemorate the fine seamanship which made possible the survival of the ship in such tempestuous conditions, and one was issued to every officer and member of the ships company. The expected wrangle over which nation was to annex Western Samoa was averted in favour of Great Britain, there being no other foreign warships left to dispute her claims! After a mixed and interesting career, Calliope was finally sold for breaking up in 1951.