- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- November 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Leslie Kilmartin

‘What’s an Orkney lad, whatever, if he’s not to have a taste o’ the dangers of the sea?’ Robert Leighton (2004)

William Cromarty arrived to settle in New South Wales in 1822. Born in South Ronaldsay, one of the more than 70 islands in the Orcadian archipelago, he was baptised in the Peterkirk on 25 November 1788. This was the last official record of him until his marriage in the same church to another Orcadian, Cecilia Brown, in 1815. As we shall see, by 1818 he was well established as a first officer on an ocean going vessel. We can therefore assume that he went to sea at an early age.

By the 1820s, he was a well-known and respected mariner in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. From the earliest times in the colony and until his death, his name has been associated with Port Stephens with landmarks such as Cromarty’s Bay, Cromarty Bay Road and Cromarty Creek.

In this essay, I will outline the main features of his life as a mariner while my book The Elusive Captain William Cromarty has more about his life as a settler in Soldiers Point, Port Stephens.

Cromarty the Boy in Orkney

Orkney Boys were introduced at an early age to fishing and sailing and Thomson (p. 214) says that, ‘nothing could excel the passion of the young men for a seafaring life’. Orkney boys and men were highly prized crew on commercial fishing and whaling fleets. Many Orcadian boys and men found employment in foreign fleets such as those that could be at sea for three of four months at a time, in the distant waters off Greenland and Iceland, harvesting whales. By 1779 three quarters of the Hudson Bay servants of the company were Orcadians (Thomson, 1987).

The Oxford Encyclopaedia, Vol V, 1828 entry for Orkney Islands describes Orkney mariners of the time as ‘remarkably bold, active, dextrous and hardy’. The Hudson Bay Company found Orkney men ‘literate, numerate, docile but tough, conscientious’.

Cromarty and the Colony

In 1818 Cromarty sailed as first officer on the convict ship Tyne which arrived at Sydney on 4 January 1819. The Tyne would have returned to London about mid-1819 after which Cromarty becomes elusive again. It’s not until March 1822 that we find him again. Once more, he’s a first officer this time on the brig Fame bound for New South Wales.

Within a few shorts weeks of arrival, Fame was chartered by Simeon Lord, a wealthy and influential businessman and former convict. Cromarty sailed cargo and passengers from Sydney to and from the cedar grounds of Port Stephens and to and from Port Dalrymple (Launceston). Lord employed Cromarty for some years.

In her description of colonial Sydney, Grace Karskens (2010) records that Lord’s house was beside the bridge in Bridge Street and rose to four storeys, the top floor containing ‘fourteen small rooms for visiting sea captains staying on shore with their goods’.

Cromarty obviously had a close business relationship and perhaps even a friendship with Lord. William and his wife Cecilia named their daughter, the first of the children to be born in the colony, Mary Louisa Lord Cromarty. Mary was the name of Lord’s wife and Louisa one of his daughters. It may be that Cromarty resided at Lord’s mansion in one of the rooms Lord kept for visiting Captains.

It was inevitable that Cromarty’s skills would be highly prized in the developing colony. When Robert Dawson arrived at Port Stephens to set up the Australian Agricultural Company (AACo) in early 1826, Cromarty already had a presence in the area. Dawson soon called upon Cromarty’s skills as mariner exploring the coast to the north of the Company settlement. He described Cromarty as ‘an able sailor’ and ‘experienced seaman’.

Dawson’s successor in early 1830 was Sir Edward Parry, the former Royal Navy captain and respected Arctic explorer. He also employed Cromarty not only for his mariner skills but also as a manager of convict workers. He clearly had a high opinion of Cromarty whom he described as a ‘rara avis’, a rare bird because of his honesty.

Cromarty’s career as a mariner was not, however, unblemished and an event in 1826 gives us an insight into his personality. In July of that year, he took a decision that could have cost him his life and his ship. He was returning from Launceston to Sydney as master of the Fame and he declined to take on a pilot. A newspaper report suggests that this was because ‘he was so well acquainted with the harbour himself’.

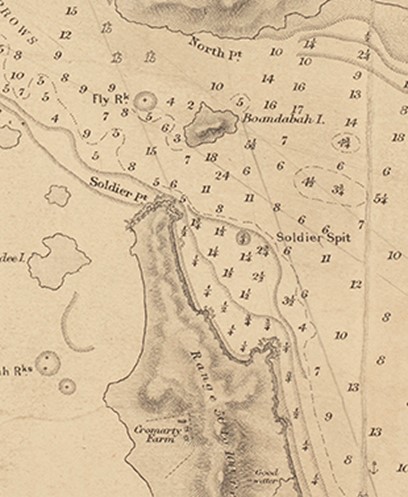

F.W. Sidney R.N. 1866 State Library of New South Wales. Although the map was drawn after

Cromarty’s death, it shows the presumably original boundaries of Ronaldsha, together with three buildings. These may have included the dwelling and the store from which Cromarty’s wife

Cecilia was said to sell supplies to ships’ crews, passers-by and aborigines.

Cromarty was obliged to anchor outside the entrance presumably due to weather and the late hour of the day. One of the harbour pilots, Captain Siddins, ‘very politely’ put Cromarty on shore at South Head. The following morning, when the pilot took Cromarty back on board, Cromarty declined his offer to pilot the Fame into the harbour.

However, the wind picked up and Cromarty was obliged ‘to let go her chain cable and anchor’. The Fame was now in danger so Cromarty ‘made the signal for a pilot, and fired again to announce she was in distress’.

‘Despite the boisterous weather and the risk’, the report continues, the pilot promptly obeyed the call and saved the Fame. The report concludes that Cromarty ‘thought it a prudent step to save his owner the expense of pilotage’. This was ‘penny wise and pound foolish’. The owner of the Fame was Simeon Lord.

By the mid-1820s, Cromarty had decided to take up his grant of 300 acres on Soldiers Point where he commenced farming while continuing some mariner work, especially for the AACo. The image below shows his property boundaries and three structures. Although the map was drawn in the 1850s, it probably depicts the details extant at the time of his death.

It was in 1834 that another opportunity arose for Cromarty to resume life as a mariner.

Cromarty as Newcastle Harbour Pilot

On 13 October 1834, Cromarty was appointed by William Nicholson, Harbour Master at Sydney to the situation of pilot at Newcastle. Nicholson recorded that Cromarty ‘is the person who was so strongly recommended by Sir E. Parry’ and wrote that ‘from the knowledge I have had of him for some years past, I am assured that I shall not be disappointed in the opinion I have formed of him as an active and intelligent seaman’.

The Sydney Gazette wrote in March 1834 that:

In no harbour or river of the Colony is the necessity of a pilot more urgent than in that of the Hunter. Large vessels occasionally touch and many would probably do so if they were provided with a public pilot, responsible for the safe navigation of the river.

The letter from Nicholson refers to ‘accompanying testimonials’ as to ‘his fitness for the situation’. John Laurio Platt, a former acting master in the Royal Navy, wrote that Cromarty was ‘a very industrious, worthy man’ who ‘combined all the qualities necessary for a pilot, sober, industrious and an excellent seaman.’

He continued that ‘not only has he a complete knowledge of the Harbour of Newcastle, but also that of Port Stephens which is necessary in certain winds to be able to run for the latter port when it is impossible to enter Newcastle’. Nicholson concluded that Cromarty’s appointment ‘would give general satisfaction to all persons concerned in the trade of the Hunter’.

Nicholson was required to conduct an examination of Cromarty and he chose three examiners who concluded that Cromarty was ‘a perfect seaman, and from his knowledge of the Port of Newcastle and also the various Harbours on the Coast to the Northward of Port Jackson’ he was ‘well qualified to take charge of any description of vessel entering Newcastle Harbour.

Cromarty took up the post of pilot in October 1834 but a serious work injury forced him to retire after only 14 months.

The King William Incident

The final chapter of Cromarty’s life may provide another insight into his personality.

On 20 August 1838, the steamer King William left Green Hills (now Morpeth), on the southern side of the Hunter River. She was bound for Sydney with five cabin passengers. One of those passengers, and the likely author of the account in The Colonist 29 August 1838 was John Dunmore Lang who founded that newspaper in 1835. Charles Payne was the captain.

The King William, originally a London river boat, had left Newcastle and was near Broken Bay when a ‘smart gale’ came up toward evening. She pressed on and about 11 pm was ‘within six or eight miles of the Heads (the entrance to Sydney Harbour) when ‘vainly contending with the wind and the waves she was struck by a sea which laid her upon her upon her beam-ends’. The situation was perilous but Captain Payne was able to right her, assisted by the fact that she tipped toward the paddle box side.

Captain Payne decided to attempt to return to Newcastle and had reached the entrance to the harbour, dangerous in the best of conditions, when the ship alarmingly turned her broadside to the wind. The captain resorted to hoisting the foretop mast sail on the steamer, the other sails having been ‘blown to pieces during the night’.

At this point, Captain Payne ‘had no other resource but to run for Port Stephens.’ In the view of the author of The Colonist report, it was providential that there was such in the vicinity as the ship could not have ridden out another night at sea in such weather.

She ploughed through heavy seas and was within sight of the South Head of the harbour when her stern boat was lost overboard. The rough conditions had obviously torn her away from the davit by which she should have been secured to the stern of the ship.

The following account is based on that in the Sydney Morning Herald of 19 September 1838.

A message was sent to Newcastle about the loss of the stern boat, presumably by Captain Payne from Nelson Bay. Such a loss would be unlikely to be replaced easily and represented a financial loss to the owners. For Captain Payne, it might have been a criticism of his seamanship or the care with which the stern boat had been secured. In any event, it would have been imperative to retrieve the stern boat if possible.

It is not known to whom the message was addressed, but it led to a letter being sent to Cromarty by Major Crummer, a police magistrate in Newcastle, and a Mr White.

Crummer and White were seeking Cromarty’s assistance in retrieving the stern boat and returning it to the Lady Blackwood at Nelson Bay. Cromarty’s nearby residence and his reputation as an able mariner would have made him the logical choice for such a mission.

The letter to Cromarty was carried by a runner who, according to a report in the Sydney Morning Herald, was lost for three days in the bush. He eventually got to the Tigress, a whaler, lying in Nelson’s Bay. Men from the Tigress conveyed him in a boat to Cromarty’s place, at Soldiers Point.

The runner told Cromarty that he’d seen the boat lying to the south on One Mile Beach. On Friday 31 August, Cromarty sailed the man back to Newcastle, on their way, ‘examining’ the boat. He then sailed the man back to Newcastle putting him on the northern beach but not attempting to enter the dangerous harbour. Cromarty returned to Port Stephens the same day.

The next day, Saturday 1 September, Cromarty started early in the morning with his son William, an assigned servant James Caton (or Catton), and a ‘native black’, each taking an oar, and walking to the place where the boat was lying. They’d taken no provisions, anticipating an early return.

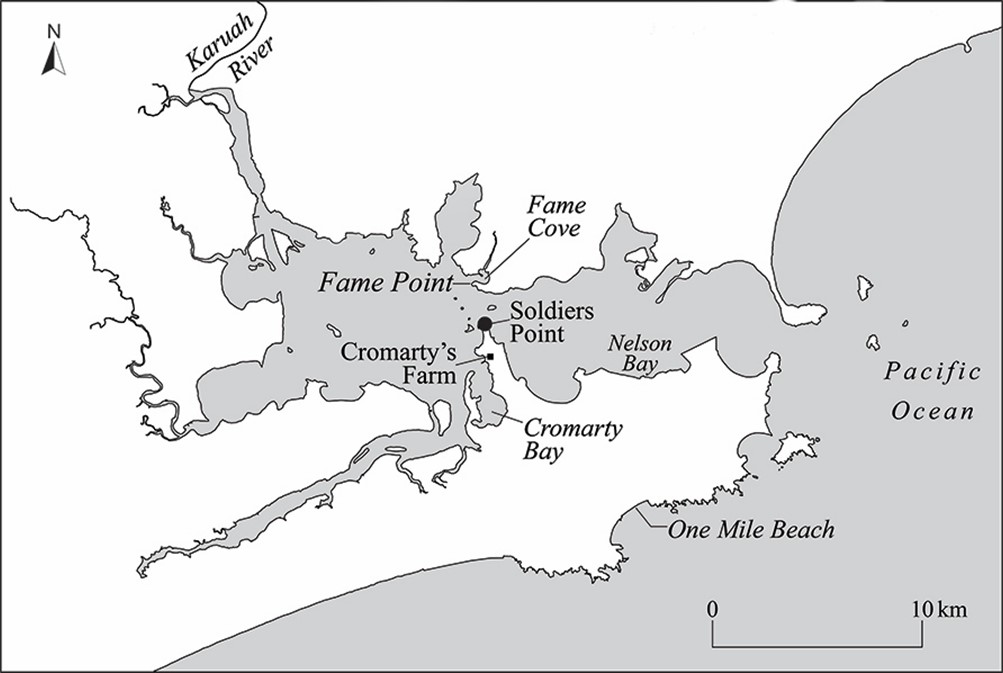

Soldier’s Point and the site of Ronaldsha. Note also Fame Point and Fame Cove. One Mile Beach is where Cromarty and his party perished.

The Herald report continues that ‘to-wards evening, his wife was anxiously expecting him and when night came without his arrival, was in a dreadful state of suspense’. The following morning, Sunday 2 September, a ship, the Lady Blackwood was sighted en route to Port Stephens. It was hoped that Cromarty and the others were on Lady Blackwood and were being taken to Nelson Bay.

Alas, the captain of the Lady Blackwood said ‘he had seen nothing of them’. Then, the ‘dreadful truth was suspected’, reported the Herald.

Soon after, a native man, Bill Wicki, was ‘sent in search’, presumably along the beach. Within a few hours, he returned with Cromarty’s boots, his son’s shoes, and Caton’s hat. He told how he’d found the stern boat ‘bottom upwards, with three oars lying a short distance off’. In a later search the Herald reported ‘The poor old gentleman’s snuff-box has since been found, but no traces of the bodies have been discovered’.

How did the recovery party meet their end? The Herald records:

Of course the exact method in which these unfortunate people came to their death is not known, but it is presumed that they launched the boat off the beach, but that before they could get her clear of the surf, which beats in very heavily, she was turned over by the rollers and went on shore again but that the bodies were caught by the drawback and taken so far out that the return of the surf did not bring them on shore.

Cromarty’s standing, even in Sydney, is clear from the Herald’s article:

We alluded in a late number, to the melancholy death of Mr. Cromarty well known to the old hands, in this Colony as captain of the old brig Fame…Mr Cromarty was a very worthy man, and was very much respected.

The AACo arranged for the remains of the three men to be buried on the Company land at Carrington where William Cromarty’s grave with headstone and foot stone remains. Sadly, the grave is on private property and is not open to the public.

In summary, we see in Cromarty an accomplished mariner who left his homeland and made a significant contribution to the development of the colony as a mariner and as a settler. We see in him great strength of character and self-belief. Perhaps it was these traits that caused him at times to take risks, to rely too heavily on his own judgement. Perhaps this is what led to his ultimate demise and that of the others in the King William incident. It is a sad irony that the oceans which Cromarty has been sailing for decades finally claimed him.

References

Karskens, Grace (2010), The Colony: a History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin

Leighton, Robert (2004), Pilots of Pomona: a Story of the Orkney Islands, BiblioLife

Thomson, William P. L. (1987), History of Orkney, The Mercat Press