- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Ship histories and stories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

A previous edition of this magazine (March 2017) outlined the exploits of HDML 1321 and favourably mentioned her commanding officer, Lieutenant Ambrose Palmer, RANR. This article explores an earlier career of this extraordinary officer when serving with the Australian Army.

Army Ketch AK 121 was launched in 1936 as a mission trading vessel from the yard of the respected Brisbane shipbuilder Norman R. Wright. She was wooden craft 65 feet in length, displaced 50 tons and was fitted with an auxiliary engine. She had the lines of a lugger which would hardly arouse suspicion, being similar to many other vessels in our northern waters. She had a good turn of speed under sail and a handy 8 knots under power. With many newly constructed vessels requisitioned by the Navy she was an unexpected find when the Australian Army was searching for a special purpose reconnaissance vessel. Before continuing with her story it is helpful to know something of the background, which all started with an anthropological lecture.

Donald Thompson

Donald F. Thomson (1901-1970) graduated in biology from the University of Melbourne in 1925, before studying anthropology at the newly established department at the University of Sydney. He spent periods of fieldwork in Cape York between 1928 and 1932, and obtained his PhD in 1934.

The harvesting of trepang (sea cucumbers) had been conducted off the coast of northern Australia for generations and formed a useful trade between Macassan (from the Celebes) and later Japanese fishermen, and the local community. With European expansion restrictions were placed on this trade and much of the coastal land was declared an Aboriginal Reserve, with non-Aboriginals requiring an entry permit. In September 1932 five Japanese trepangers who had come ashore at Caledon Bay without permits were met with hostility and killed. It is alleged they were speared to death by Yolnu men after their mothers had been raped by the Japanese. One other Japanese escaped and was able to give evidence of the incident.

Marsden Hordern, the son of a clergyman, recalls conversations with the controversial Keith Langford-Smith, who was Superintendent of the Roper River Mission in the early 1930s. These include tales of Japanese abducting young female aborigines, keeping them on board their luggers as sex slaves, and then dumping them ashore often pregnant, and/or with some venereal disease for them to spread among their people.

In the same area, two white men were killed the following year in a dispute over native women. Later in 1933 a party of mounted police was sent from Darwin to investigate and during the arrest of ringleaders a police constable was speared to death.

This situation, known as the ‘Caledon Bay Crisis’, triggered panic in the Territory, generating fears of an uprising. In what became known as the Peace Expedition, a group of unarmed missionaries agreed to negotiate with the Caledon Bay people. They believed the killer of the police constable, Dhakiyarr, acted in defence of his family and convinced him to accompany them to Darwin. Dyakiyarr was tried and found guilty but such was the national furore that the Commonwealth Government quashed his sentence. Dhakiyaarr was freed but never seen again. Questions about his disappearance and the possibility of police complicity created renewed unrest in Arnhem Land. The Commonwealth Government was concerned, as during a previous punitive expedition near Alice Springs in 1928 about one hundred Aboriginal men, women and children are alleged to have been killed in an event known as the ‘Coniston Massacre’, in which police were involved and which attracted international criticism. There was also pressure from the Japanese Government to provide answers regarding the protection of its citizens.

To diffuse this tense situation Donald Thomson sought permission to return as a mediator and between 1935 and 1937 traversed wide areas of this land and established close relations with its people. Many thought his mission suicidal but this brave and determined man succeeded. His report recommended the release from jail of the ringleaders and their return to their native country, and this was accepted. Thomson’s work in overcoming this crisis was seen as a defining moment in the history of Aboriginal-European relations, calling for improved understanding of the needs of indigenous Australians.

In 1938 Thomson accepted a prestigious fellowship at Cambridge University but less than two years later a promising academic career was interrupted by the start of WWII. Thomson returned home and on 8 January 1940 enlisted as a Flying Officer in the RAAF, posted to Port Moresby as an Intelligence Officer. Here he was involved in establishing the Coastwatching system in the Solomon Islands.

On 11 June 1941 Flight Lieutenant Thomson delivered a lecture at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne to a large audience which included many senior officers from the three services. The title of the presentation wa sArnhem Land and the Native Tribes who inhabit that area. This lecture stimulated Lieutenant Colonel W. J. R. Scott, DSO, Director of Special Operations, to obtain Thomson’s secondment to the Army with immediate promotion to Squadron Leader. After initial training, on 15 September 1941 Thomson was posted as Officer Commanding Coastal Patrol and Reconnaissance.

Find me a Ship and a Crew to sail her by

One of the new CO’s first tasks was to find a suitable vessel and then select personnel for the undertaking. Thomson was aware of Aroetta and thought she might meet his requirements.

The personnel required needed to be experienced in the operation of small ships and navigating in largely uncharted waters. Secondly they should be experienced in working with local labour. Of the men he knew from his recent experience in the Solomons, two stood out; these were Ambrose (Ernie) Palmer and Thomas (Tom) Elkington. Both had worked in small ships, they were accustomed to working alone for long periods, and were used to native labour as they had acted as recruiters of native labour in the Solomons.

Palmer had some claim to prior military service as he was in the OTC at boarding school in England. His name had also been entered on a Special Reserve List for potential service with the Royal Navy. When war broke out he approached RN authorities about joining but was told he should try the RAN. Accordingly he closed his plantation and sent his wife and children to live near her parents in Brisbane. As he had experience as a master of a trading vessel he worked his passage, thereby saving another fare. Ernie Palmer then applied to join the RAN but was knocked back, so he joined the Army.

Tom Elkington had also gone to Brisbane to enlist. And so it was that fate intervened and both men were approached and asked to volunteer for special service on hazardous enterprise within the Australian Army. They accepted and were immediately enlisted as corporals in the AIF, joining the Infantry Training Centre at Enoggara for specialist training in small arms and demolitions. On completion of training they were promoted sergeants. A third man who had served in the Solomons was Sergeant K. R. Harvey. He was engaged as the communications (WT) specialist.

The men were now split up; Palmer was sent to find and inspect Aroetta and after she was selected, to stand by her in Townsville and oversee her conversion from essentially a fishing vessel to an armed patrol boat. Most importantly was the replacement of the low powered auxiliary engine with a new and reliable 120 hp diesel engine. She also needed armament, with two Vickers machine gun mountings installed, plus various small arms and ammunition and long-range communications.

Elkington was placed in charge of recruitment and sent to the Solomons to find six reliable natives who volunteered to enlist in the AIF. They were then despatched to Townsville to join Aroetta.In addition one Torres Strait Islander, a fine seaman who had served with Thomson and knew the Arnhem Land coast and local language, was engaged as Bosun.

While fitting out was being completed and overseen by Palmer, Elkington was putting the rest of the team through a training program. Thomson meanwhile took a flying boat to Darwin to confer with the Commandant, and he was made aware of a Land Reconnaissance Party known as the 2/4th Independent Company, based at Katherine. This company was to carry out a guerrilla/reconnaissance role in the triangle made by Birdum-Groote Island-Anson Bay, and was to maintain contact with Thomson.

The Special Reconnaissance Unit

The Special Reconnaissance Unit finally sailed under Thomson’s command for Darwin, which they reached in late January 1942. Here they took on stores and engaged the final member of their crew, Raiwalla, a local full-blooded Aboriginal from the Clyde River in Central Arnhem Land. They sailed on 12 February 1942 for the Arnhem Land coast with the aim of gaining the support of isolated Aboriginal communities in the fight against the Japanese. It was noteworthy that they just missed the huge Japanese air raid on Darwin which occurred on 19 February.

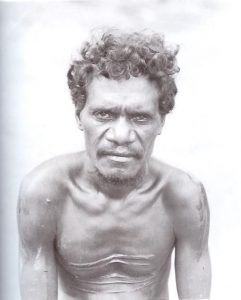

They first landed near Blyth River where Raiwalla gathered young men from the local area and they formed No 1 Section of Thomson’s Special Reconnaissance Unit under Corporal Raiwalla’s command. Two more sections were formed, comprising men from the Arnhem Bay and Caledon Bay areas. During March, Thomson trained his complement of 50 recruits at Roper River for guerrilla fighting, reconnaissance and scouting. While these new recruits were given provisions, they had no uniforms and were not given firearms but had to rely on native weapons; they received no form of payment. Later relating his experiences, Ernie Palmer says: The local warriors could hit a post at a range of a hundred yards with throwing sticks and spears, and could just as quickly make themselves disappear behind scant cover. These lanky whipcord men, as hard and tough as biltong, could run fast and leap incredible heights and their astounding skills as trackers was proverbial.

The irony of White Man’s Rules was not lost on the Indigenous community. A few years earlier Aboriginals had been threatened with capital punishment for killing Japanese entering their lands and now they were encouraged to kill Japanese with impunity as enemies.

The value of the Reconnaissance Unit was never tested as the Japanese failed to land on our shores. But the concept of raising a native detachment from young fighting men who were experienced in the remote locality and could live off the country was sound. They were fierce warriors who could have been invaluable in maintaining contact and harassing the enemy during the critical months of 1942 when invasion seemed imminent. After sixteen months of constant patrols Thomson’s task was completed and by March 1943 it was apparent that the threat of a Japanese invasion had receded. When Aroetta finally sailed from their immediate area the new recruits started drifting back to their communities. Accordingly the Army Ketch Aroetta returned to Townsville, paid off on 12 April 1943 and her crew disbanded.

Subsequent Service

Squadron Leader Thomson returned to the RAAF and was later deployed to Japanese occupied Dutch New Guinea. Here he was badly wounded in action, requiring lengthy hospitalisation before he was medically discharged from the Service. In 1945 he received the honorary rank of Wing Commander and was awarded an OBE. He later returned to academia and a wonderful collection of photographs taken during his field expeditions was donated to the National Museum of Victoria. Upon his death in 1970 his ashes were flown to the Northern Territory. In a fitting tribute, with the help of the relatives of local elders he had known many years before, his ashes were scattered over the waters of Caledon Bay.

After a spell of leave with his family Ernie Palmer was offered an Army commission in the Military Sea Transport Service. An old hand in the Pacific, Lieutenant Commander Hugh Mackenzie, RANR, was 2/IC of Eric Feldt’s Coast Watching team and at once saw the potential, arranging for Ernie to be offered a commission in the RAN. This is how Ernie Palmer eventually gained his command of HDML 1321.

References

Thomson, Donald, Report on the Northern Territory Coastal Patrol and the Special Reconnaissance Unit 1941-43.Edited by John Mulvaney and issued in Aboriginal History – Aborigines in the ServicesVolume 16, published by the Australian National University, Canberra, 1992.

Hall, R. A., Major, Guarding White Australia: Aborigines’ Contribution to Northern Surveillance During the Second World War,Defence Force Journal No 29 July/August 1981, Department of Defence, Canberra.

McCarthy, Dudley, Australia in the War of 1939-1945 South-West Pacific Area First Year – Kokoda to Wau, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1959.

Riseman, Noah Jed, Defending Whose Country? Yolngu and the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit in the Second World War, Journal of Historical & Cultural Studies, LIMINA Volume 13, 2007, University of Western Australia, Perth.